Prompt Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant in Patients With Large B-Cell Lymphoma Is Associated With Lower Rates of Progression of Disease Prior to Transplant

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Abstract

Introduction

To ensure response is preserved, it is common practice to continue chemotherapy in patients with large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) awaiting autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), even after they have achieved complete or partial response (CR/PR).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients with LBCL evaluated at our institution between 2011 and 2022 to examine the effect of delay of transplant and continuation of chemotherapy past CR/PR on progression of disease (PD) prior to transplant. The association of PD prior to transplant with delayed transplant and additional chemotherapy was modeled using logistic regression.

Results

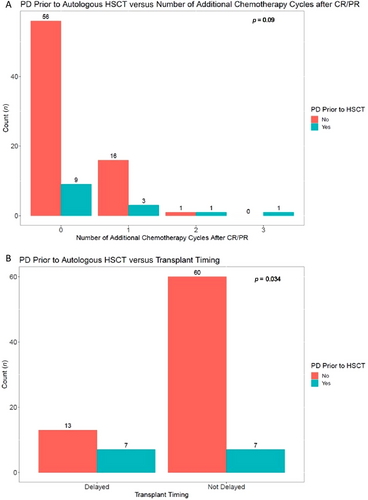

Out of the 87 patients included, 74 (85%) had relapsed/refractory LBCL. Transplant was delayed in 20 (23%) patients, and 22 (25%) patients received chemotherapy after CR/PR. Delay of transplant was associated with higher odds of PD prior to transplant (odds ratio [OR] = 4.0, p = 0.034), as was additional chemotherapy use after CR/PR (OR = 2.2, p = 0.09).

Conclusion

Proceeding to autologous HSCT as soon as adequate response is achieved in LBLC was associated with a lower likelihood of progression of disease prior to transplant regardless of additional chemotherapy receipt.

Trial Registration

The authors have confirmed that clinical trial registration is not needed for this submission

1 Introduction

Large B-cell lymphomas (LBCL) are aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas with diffuse LBCL (DLBCL) being the most common type comprising 25% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases worldwide [1]. While the majority of newly diagnosed patients achieve complete remission with standard first-line chemoimmunotherapy, up to 40% have relapsed/refractory (R/R) disease [2]. The current standard of care for patients with relapsed DLBCL > 12 months from induction therapy or localized refractory disease who have chemosensitive disease and are transplant candidates is salvage chemotherapy ± radiation therapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy (HDT) consolidation with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), which in the PARMA study led to significant 5-year overall survival (OS) benefit in those who underwent transplant versus those who did not (53% vs. 32%, p = 0.038) [3, 4]. Regardless of the salvage chemotherapy received, it has been generally accepted that adult patients with R/R LBCL need to achieve at least partial response (PR), but ideally complete response (CR), with salvage chemoimmunotherapy (typically 2–3 cycles) before they are considered eligible for consolidation HSCT [3]. Patients with transformed follicular lymphoma and Richter's syndrome undergo consolidative autologous HSCT in first remission [5, 6].

Timely autologous HSCT is considered of the essence when used for consolidation in LBCL. Until transplant evaluation starts, it is common practice for patients to receive continued therapy after a confirmed CR/PR to ensure disease control if there is a delay in transplant. However, there is no known evidence to support this practice, and thus it is unclear if the benefit of administering additional chemotherapy outweighs the risk in patients awaiting transplant. The purpose of this retrospective study is to evaluate this common practice, for which evidence is lacking. We hypothesized that because responders may have measurable or minimal residual disease (MRD) resistant to salvage chemotherapy, the receipt of continued chemotherapy beyond achieving CR/PR may not stave off progression of disease prior to transplant, especially if the transplant is delayed. The primary objective of the study was to determine if patients with LBCL status post chemoimmunotherapy in CR or PR, who either received or did not receive continued therapy while awaiting autologous HSCT, remained in CR or PR at the time of the planned transplant. Secondary objectives were to determine the median time of the transplant planning process, as well as reasons for delay in transplant necessitating continuation of therapy past CR/PR disease status and impact on progression of disease prior to transplant. Other secondary objectives of the study were to evaluate if the patients who continued to receive therapy while awaiting autologous transplant experienced treatment related toxicity, issues with stem cell mobilization and collection, and if their clinical outcomes (progression-free survival [PFS] and OS) posttransplant differed from those patients who did not receive extra therapy.

2 Materials and Methods

Approval for retrospective review of patient records between January 2011 and December 2022 was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Florida. Adult, age ≥ 18 years, both male and female, transplant eligible patients with LBCL who were being considered for consolidation with HDT followed by an autologous HSCT were included. Patients with non-LBCL pathologies, who underwent allogeneic transplant, or who were deemed transplant ineligible or decided not to undergo transplant were excluded.

Receipt of “additional” chemotherapy in patients pending transplant was defined as the continuation of therapy past the number of minimum planned cycles ± radiologic confirmation of PR or CR at the treating physician's discretion. A transplant was described as “delayed” by the treating physician.

For analysis purposes, a logistic regression was used to model the association of disease progression prior to transplant with delayed transplant and additional chemotherapy. Age, gender, and number of prior therapies were included as covariates in the regression model. Median follow-up for survivors was calculated for the transplant recipients who were alive > 30 days post autologous HSCT. Fisher's exact tests were used to study the impact of additional chemotherapy on chemotherapy-related adverse events and stem cell mobilization/collection issues. OS was determined based on the time from transplant until death or last follow-up. PFS was measured from initiation of transplant until disease progression, death, or last follow-up. Kaplan–Meier and log-rank test were used to compare PFS and OS time estimates between patients in the groups. Adverse events were graded by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0 [7].

A two-sided p value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using an R statistical programming software (version 4.1.2; R Core Team, 2021).

3 Results

3.1 Patient Population

Upon query of our institutional database, 317 patients with lymphoma were identified that were consulted by a blood and marrow transplant (BMT) physician for HSCT between January 2011 and December 2022 at the academic center. Eighty-seven patients met inclusion criteria for this study. Their baseline characteristics as well as the chemotherapy and transplant conditioning regimens they received are listed in Table 1.

| Characteristic | n = 87 (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age, range (years) | 61 (18–77) |

| Gender, male | 55 (63) |

| Lymphoma entity | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified | 60 (69) |

| Transformations of indolent B-cell lymphomas | 19 (21.8) |

| T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma | 2 (2.3) |

| EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 2 (2.3) |

| Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma | 1 (1.15) |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma/high-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 rearrangements | 2 (2.3) |

| Plasmablastic lymphoma (HIV-associated) | 1 (1.15) |

| Stage | |

| I–II | 20 (23) |

| III–IV | 62 (71) |

| N/A | 5 (6) |

| Type of first-line therapy | |

| Included CHOP | 72 (83) |

| Other (R-EPOCH, R-HCVAD, R-CEOP, R-CVP, R-GemOx, PBR, R-ICE) | 15 (17) |

| +Radiation therapy | 14 (16) |

| +Intrathecal chemotherapy | 5 (6) |

| Type of salvage therapy | |

| R-ICE | 60 (69) |

| Other (R-GCD, R-CHOP Plus R-CVP, R-CEP, R-ESHAP, BR, MTX, R-GemOx, R-GDP) | 14 (16) |

| Type of pretransplant conditioning regimen | |

| BEAM | 32 (37) |

| Bu ± Cy ± VP-16 | 39 (45) |

| CTC | 4 (5) |

- Abbreviations: BEAM, carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan; BR, bendamustine, rituximab; Bu/Cy/(VP-16), busulfan, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide; CEOP, cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine, prednisone; CEP, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, prednisone; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, daunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; CTC, cyclophosphamide, thiotepa, carboplatin; CVP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone; EPOCH, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin; ESHAP, etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin; GCD, gemcitabine, carboplatin, dexamethasone; GemOx, gemcitabine, oxaliplatin; HCVAD, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone; ICE, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide; PBR, polatuzumab vedotin, bendamustine, rituximab; R, rituximab.

3.2 Number of Chemotherapy Cycles Received and Timing of Transplant

Autologous HSCT was considered for R/R LBCL in 74 (85%) patients and as part of first-line therapy for LBCL in 13 (15%) patients. Fifteen (17%) patients had primary refractory disease.

The median number of salvage chemotherapy cycles received by patients (n = 59) with relapsed disease was 3 (range, 2–8). Forty-two patients did not receive additional cycles after achieving CR/PR; 17 patients (3 in PR and 14 in CR) received additional cycles, with a median of 1 (range, 1–3) additional cycle. Five experienced disease progression despite receiving additional cycles.

The median number of salvage chemotherapy cycles received by patients (n = 15) with primary refractory LBCL was 3 (range, 1–6). Twelve patients did not receive additional cycles after achieving CR/PR; 3 patients (1 in PR and 2 in CR) received 1 additional cycle each. All 3 had disease progression despite receiving additional cycles.

For patients who received transplant as part of first-line therapy (n = 13), the median number of chemotherapy cycles received prior to CR/PR was 4 (range, 2–6). Eleven patients did not receive additional cycles after achieving CR/PR; 2 patients in CR got 1 additional cycle each. None had disease progression prior to transplant.

Transplant was delayed in 20 (23%) patients due to medical issues (n = 13), administrative issues (n = 5), or both (n = 2). Delay occurred in 16 out of 59 patients with relapsed LBCL, 2 out of 15 patients with primary refractory disease, and 2 out of 13 patients with LBCL who received transplant as part of first-line therapy. Of the patients who had medical issues, 5 (25%) required treatment for an infection; 3 (15%) required management for a medical condition(s) (seizures, atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, gastric ulcer, renal failure, alcoholism, anxiety/depression); and 1 (5%) each required treatment of both an infection and a medical condition (small bowel obstruction), needed treatment of an infection/medical condition (urinary tract infection due to ureteral obstruction) plus experienced failure to mobilize/collect stem cells, had a collected stem cell product positive for infection, needed retreatment for LBCL, and required time for smoking cessation. Of those patients who had administrative issues, 3 (15%) experienced delay due to their medical insurance, 1 (5%) due to scheduling around the holidays, and 1 (5%) due to scheduling of the initial consultation for transplant. In addition, there were 2 (10%) patients with medical insurance issues, one of whom also needed dental work and another who needed both dental work as well as treatment for an active infection.

After their evaluation, 12 (14%) patients did not undergo transplant (5 of whom had additional chemotherapy): 7 experienced progression of disease requiring alternative therapy, 3 failed stem cell mobilization/collection, and 2 were ineligible due to high-risk comorbidities. Transplant recipients included 50 out of 59 patients with relapsed LBCL, 13 out of 15 patients with primary refractory disease, and 12 out of 13 patients with LBCL who received transplant as part of first-line therapy. For those who underwent a non-delayed transplant (n = 58), the median time between the initial consultation for transplant and the autologous HSCT was 79 (range, 30–305) days, while for those who underwent a delayed transplant (n = 17) 144 (range, 55–415) days.

3.3 Additional Chemotherapy Receipt and Delay of Transplant in Association With Progression of Disease Prior to Transplant

A total of 14 out of 87 (16%) patients (13 in CR, 1 in PR) experienced progression of disease prior to transplant; 7 had a delayed transplant. Twenty-two out of 87 (25%) patients received additional chemotherapy, 5 of whom relapsed. Seven out of the 22 patients who received additional therapy had a delayed transplant, 2 of whom relapsed. A higher number of additional chemotherapy cycles after confirmed CR/PR was associated with higher odds of progression of disease prior to transplant, although the finding was not statistically significant (odds ratio [OR] = 2.2, p = 0.09) (Figure 1A). Delay of transplant was associated with significantly higher odds of progression of disease prior to transplant (OR = 4.0, p = 0.034) (Figure 1B).

In patients with relapsed and primary refractory LBCL only, a higher number of additional chemotherapy cycles after confirmed CR/PR continued to be associated with a higher, nonsignificant odds of progression of disease prior to transplant (OR = 2.1, p = 0.12). Delay of transplant continued to be associated with significantly higher odds of progression of disease prior to transplant (OR = 3.9, p = 0.04).

3.4 Chemotherapy Related Adverse Events and Stem Cell Mobilization/Collection Issues According to Receipt of Additional Chemotherapy

Adverse events to the chemotherapy preceding transplant occurred in 27 (31%) patients and are listed in Table 2. Twenty-three patients had high grade, 3–4, toxicity. Additional chemotherapy receipt was not significantly associated with adverse events of any grade (OR = 0.79, p = 0.8).

| Patient | Adverse event(s) | CTCAE grade (1–5) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Confusion Headache requiring hospitalization |

3 3 |

| 2 |

Multiple incidental pulmonary embolisms Infection requiring treatment with oral antibiotics |

2 2 |

| 3 |

Peripheral sensory neuropathy New tremor in the hands |

2 2 |

| 4 |

Weakness requiring wheelchair use Coagulopathy with elevated INR requiring hospitalization |

3 3 |

| 5 |

Atrial fibrillation Thrombus requiring anticoagulation Seizure |

3 3 3 |

| 6 | Anemia | 3 |

| 7 | Acute kidney injury on chronic kidney disease | 2 |

| 8 |

Atrial fibrillation Gastric ulcer Diplopia |

3 3 3 |

| 9 | Febrile neutropenia requiring hospitalization | 3 |

| 10 | Anemia | 3 |

| 11 |

Febrile neutropenia Hematuria |

3 3 |

| 12 |

Anemia Thrombocytopenia |

3 3 |

| 13 | Shingles | 2 |

| 14 |

Febrile neutropenia due to wound infection Thrombocytopenia Febrile neutropenia |

3 4 3 |

| 15 | Febrile neutropenia | 3 |

| 16 | Febrile neutropenia | 3 |

| 17 | Sepsis | 3 |

| 18 |

Anemia Thrombocytopenia Leukopenia |

4 4 4 |

| 19 | Febrile neutropenia | 3 |

| 20 | Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response leading to syncope | 3 |

| 21 | Febrile neutropenia | 3 |

| 22 | Febrile neutropenia | 3 |

| 23 | Bacteremia | 2 |

| 24 |

Febrile neutropenia Shingles |

3 2 |

| 25 | Fungal pneumonia | 2 |

| 26 | Fungal pneumonia | 3 |

| 27 | Thrombocytopenia | 1 |

- Note: For patients with more than one type of adverse event, the grade of each event is reported. Patients with a delayed transplant are in bold.

- Abbreviation: CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.

Patients underwent mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) on Day 1–4 and through the end of apheresis with plerixafor as needed on Day 4 per standard operating procedures. Eight (9%) patients did not undergo stem cell mobilization/collection: 6 due to progression of disease (transplant was delayed for 2) and 2 due to high-risk comorbidities. For those who proceeded to the stem cell mobilization/collection process with a non-delayed versus delayed transplant, the median number of days of CD34+ cell collection for patients was 2 (range, 1–5) versus 2 (range, 1–4) days, while the median number of CD34+ cells collected was 4.77 (range, 1.86–16.12) versus 4.63 (range, 0.979–18.11) × 106 CD34/kg. Nine patients experienced issues with the stem cell mobilization/collection: three failed, with one also developing anaphylaxis requiring hospitalization and another NSTEMI requiring hospitalization; one patient developed acute renal failure leading to early discontinuation of apheresis; one patient developed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response requiring hospitalization; two patients’ post-processing cultures of the collected stem cells tested positive for infection; one patient developed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and pleural effusions requiring hospitalization; one patient had a seizure during apheresis, later found to be due to progression of disease in the cerebrospinal fluid. Receipt of continued chemotherapy while awaiting autologous HSCT was significantly associated with stem cell mobilization/collection issues (OR = 4.47, p = 0.04).

3.5 Clinical Outcomes Based on Additional Chemotherapy Receipt and Timing of Transplant

Median follow-up for survivors (n = 72) was 12.8 (range, 0.23–143.7) months. Additional chemotherapy receipt was not statistically significant for superior PFS (p = 0.3) or OS (p = 0.8). Delay of transplant was not associated with statistically significant inferior PFS (p = 0.3) or OS (p = 0.1). The type of pretransplant conditioning regimen was not statistically significant associated with PFS (p = 0.3) or OS (p = 0.5).

4 Discussion

In this study of patients with LBCL, delay of autologous HSCT in patients already in CR/PR awaiting transplant was associated with an increased likelihood of progression of disease prior to transplant regardless of additional chemotherapy receipt. However, there was no impact on PFS or OS of the patients following transplant.

Sensitivity to chemotherapy and depth of response has been used generally to determine whether patients with LBCL would proceed to autologous HSCT. Response is typically based only on clinical and standard imaging evaluation, with information about MRD not available in most cases. In patients with no overt lymphoma but positive MRD, additional chemotherapy of the same type may not prevent progression of disease if the MRD is resistant to that chemotherapy. But proceeding to autologous HSCT in a prompt manner may stave off disease progression as the conditioning regimen consists of different multidrug HDT.

Detectable MRD has been associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with LBCL. In one study, MRD identified by immunoglobulin high-throughput sequencing in the apheresis stem cell samples of 23 out of 98 patients with R/R DLBCL was associated with inferior 5-year PFS (13% vs. 53%, p < 0.001) and OS (52% vs. 68%, p = 0.05) in patients undergoing autologous HSCT [8]. Additional studies of MRD as contamination of the stem cell product have shown similar results [9-11]. Alternatively, measurement of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in the periphery is another way to determine the MRD status of patients with LBCL. High pretreatment serum ctDNA levels in the frontline and salvage settings [12], as well as serum ctDNA at baseline and at 1-month post chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy [13, 14] have been associated with worse prognosis and clinical outcomes. Measurable ctDNA has also been studied at the end of therapy to determine the need for further immediate treatment. Results of a study involving patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL status post 6 cycles of R-CHOP who had an end-therapy detectable ctDNA with new poor prognostic mutations showed benefit of proceeding to autologous HSCT in this group of patients in terms of no disease relapse [15]. In a similar fashion, MRD may be used as a tool for risk stratification and therapy adjustment in patients in CR/PR while awaiting autologous HSCT.

Minimizing toxicity to chemotherapy prior to transplant to ensure patients have preserved organ function and adequate performance status is important for patients to be able to proceed to transplant. In the present study, receipt of additional chemotherapy was not associated with the occurrence of adverse events. This may be because the type, not quantity, of chemotherapy impacts tolerance. In patients with R/R LBCL, the optimal salvage chemotherapy has not been established, but, for example, per the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group LY.12 study, R-GDP (rituximab-gemcitabine, dexamethasone, cisplatin) compared to R-DHAP (rituximab-cytosine, arabinoside, cisplatin, and dexamethasone) resulted in lower toxicity and higher scores for quality of life [16].

Successful peripheral blood stem cell mobilization and collection is key to proceeding to transplant. Our results showed that additional chemotherapy receipt has a negative impact on the stem cell mobilization and collection process, which may be due to the cumulative amount of chemotherapy. Looking at mobilization failure alone, the number of chemotherapy cycles has not been previously shown to have a negative impact, although mobilization regimens vary [17, 18].

Limitations of the study are the retrospective study design, single institution setting, limited patient number, and lack of MRD testing of the patients. A strength of this study is the availability of patient outcomes between the initial transplant consultation and potential transplant.

Improving outcomes of autologous HSCT remains important in the era of new therapies, such as anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy and anti-CD20/CD3 T-cell engager therapy, for R/R LBCL. In one analysis, despite the CAR T-cell therapy response rate being high, in 2023, the eligibility of patients with LBCL for CAR T-cell therapy was only 2.5% and response 2.1% as a percentage of patients with advanced or metastatic cancer [19]. In patients with early relapsed or primary refractory LBCL, CAR T-cell therapy has demonstrated superior survival compared to chemotherapy followed by autologous HSCT [20, 21]. In contrast, in patients with R/R LBCL in PR status post salvage chemotherapy undergoing either autologous HSCT or CAR T-cell therapy as third-line therapy, transplant has been shown to be associated with lower incidence of relapse and better OS in a retrospective analysis [22]. Given that commercially available T-cell engager therapies have been approved for after at least 2 prior lines of therapy in R/R LBCL, thus far their use has been evaluated only pre-consolidative allogeneic HSCT [23] and has not yet been assessed as a bridge to autologous HSCT [24]. These studies illustrate that sequencing, combination, and optimization of both existing and newer therapies are actively under investigation and necessary to achieve durable remission for every patient.

In conclusion, results of this study showed that proceeding to autologous HSCT as soon as adequate response is achieved in LBLC was associated with a lower likelihood of progression of disease prior to transplant. Continuation of chemotherapy in patients already in CR/PR awaiting transplant was not associated with less progression of disease prior to transplant and instead predicted for increased number of stem cell mobilization and collection related issues. Assessing the role of chemotherapy continuation past CR/PR status in this group of patients needs to be studied prospectively with MRD measurements.

Author Contributions

E.A.D. conceived of and designed the study. E.A.D. and R.Y.L. collected the data. T.L., D.M.L., and E.A.D. interpreted the data and performed all statistical analyses. E.A.D. and T.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alex J. Pastos for assistance with data sorting and processing.

Ethics Statement

Approval for this research was obtained from the IRB at the University of Florida before the start of the study.

Consent

The retrospective study was approved by the IRB at the academic center. Obtaining individual patient consents for this study was not required.

Conflicts of Interest

E.A.D. reports unlicensed patents (no royalties) related to cellular immunotherapy held by Moffitt Cancer Center in her name. J.R.W. has financial interests (consultancy) in Cidara, Celgene, F2G, Orca, Takeda; none are related to the subject of this article. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.