Clinical Outcomes of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer Patients With Concurrent Advanced Malignancies With Expected Poor Prognosis

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Aims

Despite improved outcomes for malignant tumors, evidence regarding the management of patients with multiple malignancies remains limited. We aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes and prognosis of patients undergoing endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early gastric cancer (EGC) complicated by advanced malignancies in other organs with a poor prognosis.

Methods and Results

We retrospectively reviewed 3703 gastric cancer patients who underwent ESD at our hospital (2005–2022), focusing on those with advanced extra-gastric malignancies with a 5-year survival rate of < 50%. ESD was performed for local tumor control based on patient preference when feasible, including lesions meeting standard, expanded, or relative indications where curative resection was unachievable. Clinicopathological characteristics and outcomes were analyzed. Twenty-six patients met the inclusion criteria. En bloc resection was achieved in all cases (100%), with curative and non-curative resection in 16 (62%) and 10 (38%) cases, respectively. None of the 10 patients with non-curative resection exhibited lymphovascular invasion or GC recurrence. Complications included delayed bleeding, perforation, and pneumonia, each in one patient (4%), all leading to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and death within 30 days post-ESD. Notably, no complications were reported after 2010. Eleven patients died from advanced malignant tumors, with no GC recurrences observed during follow-up in surviving patients.

Conclusions

Recently, no severe complications have been observed with ESD. Although ESD for local control in EGC with concurrent advanced extra-gastric malignancies may be acceptable, the risk of severe complications, including DIC, remains. Therefore, careful patient selection and thorough informed consent are essential.

1 Introduction

Recently, notable progress has been made in malignant tumor treatment, including advances in minimally invasive surgery [1], the development of chemotherapy options such as immune checkpoint inhibitors [2], and the introduction of drugs to mitigate chemotherapy-induced side effects [3]. Consequently, patient prognosis has improved, leading to an increase in the number of individuals diagnosed with multiple primary malignant tumors. However, there is currently no evidence-based guidance on the optimal treatment strategies for patients with multiple primary malignant tumors.

Gastric cancer (GC) remains highly prevalent in East Asian countries, including Japan, Korea, and China [4, 5]. Early gastric cancer (EGC) complicated by advanced malignant tumors of other organs presents a clinical challenge, particularly in determining appropriate treatment indications. Factors such as patient performance status (PS) play a crucial role in treatment decisions, as those with low PS may not be suitable candidates for surgery. In such instances, the prognosis of the advanced malignancy often becomes a key factor in determining the course of treatment for coexisting EGC.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has become a widely accepted, minimally invasive therapy for EGC, offering organ preservation and improved quality of life, especially in older patients [6]. However, evidence regarding ESD efficacy and safety in patients with advanced malignancies of other organs remains limited. Previous studies, such as the one conducted by Akasaka et al., have shown ESD to be relatively safe, with low rates of perforation, postoperative bleeding, and pneumonia, and no reported deaths [7]. Nevertheless, EGC treatment in patients with advanced malignancies in other organs should be carefully considered, particularly when the prognosis of the advanced GC of other organs is expected to be better than that of EGC. The natural history of untreated EGC has shown that the median time for progression to advanced carcinoma is 34 [8] to 44 [9] months, with a 5-year corrected survival rate of 62.8% for unresected cases [9]. In another study analyzing 12 cases, EGC progressed to advanced cancer within a median of 9.6 months, with a 5-year survival rate of 45% [10].

Accordingly, ESD treatment for EGC in patients with advanced malignancies and a 5-year survival rate exceeding 50% is considered a reasonable approach. However, in cases where the advanced malignancy has a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate below 50%, the malignancy itself may be the primary prognostic factor. In such cases, determining whether to treat the coexisting EGC can be challenging.

EGC that coexists with advanced malignancies in other organs with a 5-year survival rate below 50% may not directly cause death, but instead can progress to advanced GC over time. This progression may lead to complications such as bleeding, obstruction, or anemia, potentially interfering with chemotherapy for the advanced malignancy [11]. Given the poor surgical tolerance in these patients, ESD may be a reasonable option to prevent such complications. However, EGC treatment may not always be appropriate depending on the overall prognosis. We retrospectively analyzed patients with EGC with primary malignancies in other organs (5-year survival < 50%, PS 0–1). ESD was performed based on patient preference in cases where local endoscopic resection was deemed feasible. This included not only lesions meeting the absolute indications or expanded indications for ESD but also those with relative indications where curative resection was considered unachievable.

This study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes and prognosis of ESD in patients with EGC with advanced primary malignancies in other organs with a 5-year survival rate of < 50% and to assess the risks and benefits of ESD in this complex patient population.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Patients

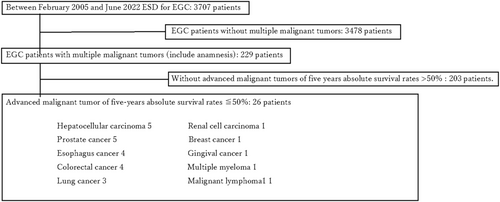

In this retrospective study, we enrolled 26 patients with advanced malignant tumors of other organs, including metachronous cancer. All patients had a 5-year absolute survival rate of < 50%. These patients were selected from a cohort of 3703 individuals with GC who underwent ESD at our hospital between February 2005 and June 2022 (Figure 1). Clinicopathological characteristics and ESD outcomes were evaluated. Definitions of multiple primary malignant tumors were based on criteria established by Warren and Gates in 1932: (1) histological confirmation of malignancy for each neoplasm; (2) distinct pathomorphological features for each neoplasm; (3) development of neoplasms in different locations without connections; and (4) exclusion of metastasis [12]. The 5-year absolute survival rate was determined based on a Japanese report [13]; the TNM staging was classified according to guidelines of relevant Japanese societies [14-20].

The study included patients with EGC who were deemed eligible for endoscopic local resection. This included lesions meeting not only the absolute indications or expanded indications for ESD but also relative indications where curative resection was considered unachievable.

Patients were thoroughly informed about the risks associated with ESD before performing the procedure. In particular, for lesions meeting the criteria for relative indications, patients were explicitly informed about the possibility of non-curative resection and the significance of local disease control. ESD was performed only for those who fully understood these considerations and opted for the procedure.

2.2 Specimen Assessment

Gastric lesions were categorized into three sections: upper third (U), middle third (M), and lower third (L) of the stomach [21]. Macroscopic types were classified as protruding (0–I), superficial (0–II), or excavated (0–III), with the superficial type further divided into superficially elevated (0–IIa), superficially flat (0–IIb), and superficially depressed (0–IIc). For tumors exhibiting ≥ 2 macroscopic types, the classification was based on the type occupying the largest surface area (e.g., 0–IIa + IIc) [21]. Patient characteristics (age, sex, advanced malignancy, and clinical stage), endoscopic findings, pathological features (tumor size, location, macroscopic type, histology, tumor invasion depth, ulceration, lymphovascular invasion, and resection margins), and ESD outcomes (en bloc resection, curative resection, noncurative resection, procedure time, adverse events, and outcomes) were documented.

2.3 Histopathological Evaluation

Following resection, a histopathological examination was performed according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma [22]. Histological types were categorized into differentiated-type adenocarcinoma (tubular and papillary adenocarcinoma) and undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma) [23]. Submucosal tumor invasion (T1b) was subclassified as SM1 (< 500-μm invasion from the muscularis mucosa) or SM2 (≥ 500-μm invasion) [23]. The assessment included ulcer examination, scar findings, and lymphovascular invasion.

2.4 Pathological Curability

The entire resection for an en bloc-resected tumor is regarded as all vertical and lateral margins with no tumors during histological examination [22].

A lesion is considered endoscopic curability A (eCuraA) when it is resected en bloc and meets the following conditions [21]: (i) predominantly differentiated type, pT1a, UL0, HM0, VM0, Ly0, V0, regardless of size; (ii) long diameter ≤ 2 cm, predominantly undifferentiated type, pT1a, UL0, HM0, VM0, Ly0, V0; or (iii) long diameter ≤ 3 cm, predominantly differentiated type, pT1a, UL1, HM0, VM0, Ly0, and V0.

A lesion is considered endoscopic curability B (eCuraB) when it is resected en bloc, has a long diameter ≤ 3 cm, is predominantly of the differentiated type, and satisfies the following criteria: pT1b1 (SM1) (within < 500 μm from the muscularis mucosae), HM0, VM0, Ly0, and V0.

When a lesion meets neither eCuraA nor B conditions, it is considered eCuraC, corresponding to the concept of non-curative resection.

2.5 Assessment of Complications

This study evaluated perforations during ESD, delayed bleeding, delayed perforation, and postoperative pneumonia. Delayed bleeding was defined as any of the following: an episode of hematemesis and/or melena, a drop of 2 g/dL in hemoglobin level, and a suspicion of bleeding requiring a new endoscopy within 30 days after ESD completion. Delayed perforation was defined as cases wherein perforation had not been detected during and just after ESD completion, but subsequent endoscopy showed perforation or computed tomography (CT) showed free air post-ESD. Postoperative pneumonia was defined as fever, decreased oxygen saturation, or pneumonia on imaging.

2.6 Clinical Outcome Assessment

Clinical outcomes were retrospectively collected from medical records from February 2005 to June 2022. Causes of death were classified as related to advanced malignant tumors of other organs, other causes, or ESD-related. ESD-related death was defined as death occurring within 30 days post-ESD.

3 Results

3.1 Patient Characteristics

Between February 2005 to June 2022, 3703 patients with EGC underwent ESD at our hospital. Among these, 229 patients had multiple malignant tumors, including metachronous malignant tumors; of these, 26 patients had advanced malignant tumors in other organs with a 5-year absolute survival rate of < 50% (Figure 1). Characteristics of these 26 patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 75 years (range 50–90 years); 81% (21/26) of patients were male. The distribution of advanced cancers included five cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (stage II in 4, stage IV in 1), five of prostate cancer (all stage IV), four of esophageal cancer (stage II in 2, stage IV in 2), four of colon cancer (all stage IV), three of lung cancer (all stage IV), and one each of renal cell carcinoma (stage IV), breast cancer (stage IV), supragingival cancer (stage IV), multiple myeloma (stage III), and malignant lymphoma (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, stage III). The clinical stages of these cancers were stage II in 6 (23%), stage III in 2 (8%), and stage IV in 18 (69%) patients. All 26 patients were undergoing treatment or pre-treatment and had good PS, with 69% (18/26) having PS 0 and the remaining (8/26) having PS 1.

| Characteristic, n (%) | (n = 26) |

|---|---|

| Median age, years [range] | 75.0 [50–90] |

| Sex, male | 21 (81) |

| Advanced malignant tumor | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 5 (19) |

| Prostate cancer | 5 (19) |

| Esophagus cancer | 4 (15) |

| Colorectal cancer | 4 (15) |

| Lung cancer | 3 (12) |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 1 (4) |

| Breast cancer | 1 (4) |

| Gingival cancer | 1 (4) |

| Multiple myeloma | 1 (4) |

| Malignant lymphoma | 1 (4) |

| cStage | |

| cStage II | 5 (19) |

| cStage III | 2 (8) |

| cStage IV | 19 (73) |

| ECOG performance status (PS) | |

| PS 0 | 18 (69) |

| PS 1 | 8 (31) |

- Abbreviations: cStage, clinical stage; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

3.2 Endoscopic Findings and Pathological Characteristics

Endoscopic and pathological characteristics are detailed in Table 2. The median tumor size was 20 mm (range 5–110 mm). The tumor location was distributed as follows: U in six lesions (23%), M in six lesions (23%), and L in 14 lesions (54%). Macroscopically, two lesions (7%) were of the protruding type, 10 (35%) were superficial elevated type, and 14 (58%) were superficial depressed type. Histologically, 88% (23/26) of tumors were of the differentiated type, whereas 12% (3/26) were of the undifferentiated type. Invasion depth was pT1a in 18 (69%), pT1b1 in three (12%), and pT1b2 in five (19%) cases. Ulcerative findings were observed in one lesion (4%), and one lesion had a positive vertical margin (VM). All lesions tested negative for lymphovascular invasion and horizontal margins.

| Variable, n (%) | (n = 26) |

|---|---|

| Median size, mm [range] | 20.0 [5–110] |

| Location | |

| U | 6 (23) |

| M | 6 (23) |

| L | 14 (54) |

| Macroscopic type | |

| Protruding type (0–I) | 2 (7) |

| Superficial elevated type (0–II) | 10 (35) |

| Superficial depressed type (0–IIc) | 14 (48) |

| Major history | |

| Differentiated type | 23 (89) |

| Undifferentiated type | 3 (11) |

| Depth of tumor | |

| pT1a | 18 (69) |

| pT1b1 | 3 (12) |

| pT1b2 | 5 (19) |

| Ulcerative findings | 1 (4) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0 (0) |

| Horizontal margin | 0 (0) |

| Vertical margin | 1 (4) |

- Abbreviations: L, lower; M, middle; pT1a, pathological T1a; pT1b1, pathological T1b1; pT1b2, pathological T1b2; U, upper.

3.3 ESD Outcomes

Table 3 outlines ESD outcomes. En bloc resection was successfully performed for all lesions. Curative resection was achieved in 16 lesions (62%), whereas 10 lesions (38%) required non-curative resection. The non-curative resection included cases with pT1b2 (n = 5), ulcerative findings with tumor size > 30 mm (n = 1), undifferentiated type with tumor size > 20 mm (n = 3), and positive VM (n = 1). The median procedure time was 66 min (range 10–330 min). Adverse events occurred in three cases (12%): delayed bleeding (n = 1), delayed perforation (n = 1), and postoperative pneumonia (n = 1). Clinical outcomes included death from advanced cancer in 11 patients (42%), death from ESD-related adverse events in three patients (12%), death from other diseases in three patients (12%), and survival in nine patients (34%). No deaths were directly attributable to EGC.

| Variable, n (%) | (n = 26) |

|---|---|

| En block resection | 26 (100) |

| Curative resection | 16 (62) |

| Non-curative resection | 10 (38) |

| pT1b2 | 5 (19) |

| UL1, > 30 mm | 1 (4) |

| Undifferentiated type, > 20 mm | 3 (11) |

| VM1 | 1 (4) |

| Median, procedure time, min [range] | 66 [10–300] |

| Adverse events | |

| Perforation during ESD | 0 (0) |

| Delayed bleeding | 1 (4) |

| Delayed perforation | 1 (4) |

| Postoperative pneumonia | 1 (4) |

| Outcomes | |

| Death due to original malignant tumor | 11 (42) |

| Death due to other causes | 3 (12) |

| ESD-related death | 3 (12) |

| Survival | 9 (34) |

- Abbreviations: ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; pT1b2, pathological T1b2; UL, ulcerative findings; VM, vertical margin.

Table 4 details three patients who died from complications. Notably, these events occurred only in procedures before 2010; in 23 procedures after 2010, no complications or deaths occurred. Of the fatalities, two had prostate cancer and one had multiple myeloma. All had tumors around 20 mm in size in the U/M with extended ESD times (up to 300 min). Two underwent non-curative resections. The patient with perforation had surgery but died from disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and uncontrolled bleeding. All three developed DIC and died within 30 days of ESD. Eleven patients died of primary advanced cancer within 4 years. The oldest patient was 90 years old and underwent ESD. Among patients who died of the original malignant tumor, five of 11 patients underwent non-curative ESD for EGC, but none died from EGC.

| Case | Date (year) | Age (years) | PS | Advanced malignant tumor | Stage | Size (mm) | Location | Procedure time (min) | Major histology | Depth | Adverse event | Survival period (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2007 | 78 | 1 | Prostate | IVb | 10 | U | 120 | Undifferentiated | SM2 | Delayed bleeding | 14 |

| 2 | 2008 | 79 | 0 | Multiple myeloma | III | 20 | M | 300 | Undifferentiated | SM1 | Delayed perforation | 30 |

| 3 | 2010 | 87 | 1 | Prostate | IVb | 22 | U | 40 | Differentiated | M | Postoperative pneumonia | 14 |

- Abbreviations: ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; M, middle; M, intramucosal; SM, submucosal invasive; U, upper.

Results of the comparative analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics between cases complicated by DIC and those without DIC are presented in Table 5. No significant differences were observed with respect to age, sex, lesion location, major history, tumor depth, lesion size, or procedure time; only the subgroup of patients who underwent ESD prior to 2010 exhibited a statistically significant difference.

| DIC group, n = 3 | Non DIC group, n = 23 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years [range] | 79.0 [78–87] | 75.0 [50–90] | N.S |

| Sex, male | 3 (100) | 18 (78) | N.S |

| ESD performed before 2010 | 3 (100) | 2 (9) | < 0.05 |

| Location | 0.123 | ||

| Upper | 2 (67) | 4 (18) | |

| Middle & lower | 1 (33) | 19 (82) | |

| Major history | 0.319 | ||

| Differentiated typed | 2 (67) | 21 (91) | |

| Undifferentiated typed | 1 (33) | 2 (7) | |

| Depth of tumor (pathological T1a) | 1 (33) | 21 (91) | 0.085 |

| Median size, mm [range] | 20 [5–110] | 20 [10–22] | N.S |

| Median, procedure time, min [range] | 72 [10–300] | 120 [40–300] | N.S |

- Abbreviations: DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection.

Clinicopathological features and outcomes of non-curative resections are presented in Table 6. Among 10 non-curative ESD cases, two patients survived for > 5 years. None of these patients exhibited lymphovascular invasion or recurrence of GC.

| Case | Age (years) | PS | Sex | Advanced malignant tumor | Stage | Location | Size (mm) | Macroscopic type | Procedure time (min) | Major histology | Depth | Outcome | Survival period (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68 | 1 | M | Esophagus | IVb | L | 30 | IIa | 120 | Differentiated | SM2 | Original | 188 |

| 2 | 50 | 0 | M | Esophagus | II | M | 35 | IIc | 300 | Differentiated | M (VM1) | Survival | 3211 |

| 3 | 75 | 1 | M | Esophagus | IVb | L | 25 | IIa | 30 | Differentiated | SM2 | Original | 500 |

| 4 | 74 | 1 | M | Renal | IV | L | 40 | IIc | 110 | Undifferentiated | M | Original | 261 |

| 5 | 77 | 0 | M | Prostate | IVb | M | 15 | IIc + IIa | 80 | Differentiated | SM2 | Original | 855 |

| 6 | 78 | 1 | M | Prostate | IVb | U | 10 | IIa | 120 | Differentiated | SM2 | ESD related | 14 |

| 7 | 81 | 1 | M | Prostate | IVb | U | 30 | I | 30 | Differentiated | SM2 | Original | 28 |

| 8 | 56 | 0 | F | Colorectal | IVa | M | 110 | IIa + I | 300 | Differentiated | M (UL1) | Survival | 1865 |

| 9 | 79 | 0 | M | Multiple myeloma | III | M | 20 | IIc | 300 | Undifferentiated | SM1 | ESD related | 30 |

| 10 | 53 | 0 | F | Breast | IV | L | 10 | IIc | 40 | Undifferentiated | SM1 | Original | 1384 |

- Note: No cases were lymphovascular invasion.

- Abbreviations: Depth M, intramucosal; ESD; Endoscopic submucosal dissection; F, female; L, lower; M, male; M, middle; SM, submucosal invasive; U, upper; UL, Ulcerative findings; VM, Vertical margin.

Clinicopathological features and clinical outcomes of 11 patients who died of the original malignant tumor are presented in Table 7. They all died within 4 years; 5 of 11 patients had non-curative ESD, but none had a recurrence of GC during the observation period.

| Case | Age (years) | PS | Sex | Advanced malignant tumor | Stage | Location | Size (mm) | Macroscopic type | Procedure time (min) | Major histology | Depth | Survival period (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90 | 1 | M | Hepatocellular | II | L | 10 | IIc | 25 | Differentiated | M | 94 |

| 2 | 84 | 0 | M | Hepatocellular | II | L | 30 | IIa | 100 | Differentiated | M | 1133 |

| 3 | 77 | 0 | M | Prostate | IVb | M | 15 | IIc + IIa | 80 | Differentiated | SM2 | 855 |

| 4 | 81 | 1 | M | Prostate | IVb | U | 30 | I | 30 | Differentiated | SM2 | 28 |

| 5 | 68 | 1 | M | Esophagus | IVa | L | 30 | IIa | 120 | Differentiated | SM2 | 188 |

| 6 | 75 | 1 | M | Esophagus | IVb | L | 25 | IIa | 30 | Differentiated | SM2 | 500 |

| 7 | 64 | 0 | M | Lung | IVa | M | 15 | IIc | 60 | Differentiated | M | 603 |

| 8 | 65 | 0 | M | Lung | IVa | L | 5 | IIc | 40 | Differentiated | M | 278 |

| 9 | 73 | 1 | M | Lung | IVa | U | 40 | IIa | 120 | Differentiated | M | 870 |

| 10 | 74 | 1 | M | Renal | IV | L | 40 | IIc | 110 | Undifferentiated | M | 261 |

| 11 | 53 | 0 | F | Breast | IV | L | 10 | IIc | 40 | Undifferentiated | SM1 | 1384 |

- Abbreviations: F, female; L, lower; M, intramucosal; M, male; M, middle; SM, submucosal invasive; U, upper.

4 Discussion

This study included 26 EGC patients with concurrent advanced malignant tumors of other organs, of 3703 GC patients who underwent ESD between February 2005 and June 2022. En bloc resection was achieved for all lesions; however, 10 lesions (38%) were classified as non-curative. Despite this, no cases exhibited lymphovascular invasion or recurrent GC. Notably, three ESD-related deaths occurred, all in cases performed before 2010.

The 5-year survival and recurrence rates for appropriately treated EGC are generally reported as > 90% and 1.0%–11.2%, respectively [23]. Herein, curative resection was achieved in 16 of 26 patients. Among 10 patients with non-curative resection, none experienced the recurrence of GC during a maximum follow-up period of 3221 days. Thus, local resection by ESD may be significant for EGC patients with advanced malignancies in other organs.

In contrast, a study of 905 patients with no additional treatment after non-curative resection by ESD for EGC reported a median survival of 28 months after ESD, with recurrence observed in 25 patients over a median follow-up of 64 months [24]. Lymphovascular invasion has been identified as a risk factor for recurrence in several studies. For example, in a cohort of 159 patients with GC who did not achieve a cure after ESD, the median survival was 27.5 months, with underlying disease and lymphovascular invasion as independent prognostic factors [25]. Risk factors for GC recurrence include lymphovascular invasion, associated with a hazard ratio of 6.6 [26], and lymphatic invasion, with a hazard ratio of 5.23 [27]. Herein, the absence of lymphovascular invasion likely contributed to the lack of recurrence and death from GC.

Furthermore, prognosis data for non-curative resections indicate that patients undergoing curative surgical resection have significantly better overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) compared to those who do not receive additional treatment [27]. However, the 3-year DSS difference between the groups was relatively small (99.4% vs. 98.7%) compared to the more pronounced difference in 3-year OS (96.7% vs. 84.0%) [27]. Although predicting lymphovascular invasion before ESD remains challenging, our results suggest that non-curative resections offer some benefit for local control in the absence of lymphovascular invasion. Careful consideration is required when deciding on additional surgery for non-curative resections, considering surgical tolerance and pathological factors.

An important result of this study is that three of 26 patients (12%) experienced complications after ESD that led to DIC and subsequent death. Among these patients, one had stage III multiple myeloma, and two had stage IVb prostate cancer. Despite all patients having a performance status of PS 0–1, the complications resulted in fatalities. Although previous reports indicate that death from ESD complications is rare [7], the presence of advanced cancers in other organs may have heightened the risk of DIC in our cohort. Therefore, careful consideration is needed when performing ESD in patients with EGC complicated by other malignancies.

Adverse events observed herein included delayed bleeding, perforation, and postoperative pneumonia. Delayed bleeding occurred in a patient with chronic kidney disease following renal cell cancer resection. Although delayed perforation after ESD for EGC is infrequent, excessive electrocautery during hemostasis may contribute to its development. The duration of cautery for hemostasis is significantly longer in cases with perforation compared to cases without perforation [28]. In addition, the U is a significant factor associated with delayed perforation [28], which may be related to the higher bleeding rate owing to the larger diameter of the submucosal arteries in U to M. [29] Herein, the procedure time for delayed perforation lasted 300 min due to the challenging lesion location and severe bleeding requiring repeated hemostatic interventions. Although we lacked video data for assessing hemostatic time, frequent hemostatic measures may have contributed to the delayed perforation.

Postoperative pneumonia was also a concern. Multivariate analysis identified several independent risk factors: age ≥ 75 years (odds ratio [OR] 2.83), cerebrovascular disease (OR 3.60), COPD (OR 2.64), delirium (OR 5.32), and remnant stomach or gastric tube (OR 5.30) [11]. A retrospective study reported a 1.6% incidence of postoperative pneumonia [7], but a separate report [30] noted that 66.7% of patients with pneumonia on CT scans had no pneumonia on chest radiography, suggesting that some cases may be overlooked. Although the exact number is not known, a certain number of cases have occurred. Although postoperative pneumonia cannot be completely avoided, early detection is possible with proper investigation, and special attention should be paid to patients with these risk factors. Aspiration pneumonia is more likely if there is significant fluid reflux into the oral cavity during esophageal ESD [31]. Measures such as proper intraoperative oral suctioning and avoiding deep sedation are necessary to mitigate this risk. In our study, an 87-year-old patient with EGC in the cardiac region experienced postoperative pneumonia, possibly due to fluid reflux from an incision made at the gastroesophageal junction. The incision was made on the esophageal side, which may have resulted in fluid reflux into the oral cavity and postoperative pneumonia. Thus, it is important to emphasize that even in patients with good PS, ESD for EGC with advanced cancer of other organs and poor prognosis may be fatal if complications arise.

Curative resection was achieved in 16 out of 26 cases. Among the remaining 10 cases, local disease control was obtained in 9, except for one case with a positive deep margin, resulting in a favorable local control rate of 96.2% (25/26). Severe complications occurred in 3 cases treated before 2010. However, no severe complications were observed in the 23 cases treated after 2010. Advances in devices and techniques in recent years [32-37] may have contributed to reducing the risk of complications. However, overall, severe life-threatening complications were observed in 3 out of 26 cases (11.5%), indicating a relatively high incidence. Given that only three cases developed DIC, it remains challenging to draw definitive conclusions regarding the risk factors for severe complications from the present study findings. In one case, it is speculated that a prolonged procedure time may have contributed to the occurrence of delayed perforation. Therefore, in cases where a longer procedure time is anticipated based on the lesion location or tumor size, more careful consideration of the indication for ESD may be warranted. Additionally, although factors such as nutritional status, performance status, and comorbidities are presumed to be important, the small number of cases in this study precluded a clear determination of their causal relationships with the development of severe complications, such as DIC. Thus, further investigation with a larger cohort is necessary. As the natural history of untreated EGC shows a median progression time of 44 months, during which tumor growth may lead to bleeding or obstruction and thereby impair patient quality of life, we sought to evaluate the outcomes of ESD in a cohort whose concomitant advanced malignancies predict a 5-year survival rate below 50%. While comparing these ESD-treated patients to contemporaneous patients with similar clinical indications who declined ESD would provide valuable insight into the appropriateness of the procedure, our institution lacked a dedicated registry of non-ESD cases.

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients with advanced cancer managed between 2012 and 2022. Within this group, we identified 17 individuals who met standard endoscopic criteria for ESD but did not undergo the procedure. In contrast to our ESD cohort, these non-treated patients predominantly exhibited poor performance status (PS 0–1, 5 cases; PS 2–3, 12 cases) or were deemed to have an exceedingly poor prognosis owing to their advanced disease. Their mean survival was only 0.9 years. Although a small number of patients with preserved PS and stable comorbid malignancies declined ESD because of personal preference—and would have constituted an ideal comparison group—such cases were exceedingly rare. Given these circumstances, any direct comparison would be subject to profound selection bias. Consequently, we concluded that it was not feasible to include a non-ESD control group for assessing the validity of ESD in early GC concomitant with advanced malignancy. Nevertheless, ESD safety has steadily improved in recent years. However, the presence of coexisting advanced malignancies may worsen outcomes in the event of complications. Therefore, careful patient selection and thorough informed consent are essential when considering this treatment.

This study has some limitations. First, this was a single-center trial with a small sample size. Second, patients who developed complications were treated before 2010, and newer endoscopic techniques for preventing complications were not fully utilized. Third, data collection was challenging for patients who did not undergo ESD for EGC with advanced tumors, preventing a comparison of their prognosis with those who did undergo ESD.

In conclusion, due to the non-negligible risk of DIC associated with ESD, it is imperative to thoroughly assess the patient's suitability for ESD treatment and obtain comprehensive informed consent before its implementation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff at the gastroenterology and pathology laboratories for their valuable support. We would also like to thank Editage (https://app.editage.jp/) for the English language editing.

Ethics Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Consent

An opt-out informed consent protocol was used for this study. The consent procedure was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hiroshima University (January 20, 2023; approval number [E2022-0237]).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.