Efficacy of 2-Mercaptoethane Sulfonate Sodium (MESNA) in the Prevention of Pancreatitis After Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography: A Randomized Open Label Trial

ABSTRACT

Background and Aim

Oxidative stress has been considered a factor in the development of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP). The present clinical trial evaluated whether adding intravenous mesna to rectal indomethacin could prevent or alleviate PEP.

Methods

An open-labeled clinical trial was done on 698 participants undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Eligible patients received 100 mg indomethacin suppository 30 min before undergoing ERCP. Randomly, the participants received 400 mg intravenous mesna or nothing 30 min before doing the procedure. The PEP incidence and degree were measured in the patients as the main outcome.

Results

The total rate of PEP was equal to 13.7%. No significant difference was seen in the rate and severity of PEP between the mesna plus indomethacin and indomethacin alone arms (14% vs. 13.4%, respectively, p = 0.671). In high-risk patients, PEP rate and severity were lower in the mesna plus indomethacin group compared with indomethacin alone group and the statistical analysis showed that the difference was significant (41.7% vs. 51.8%, respectively, p = 0.033).

Conclusion

In high-risk patients undergoing ERCP, a combination of intravenous mesna plus rectal indomethacin may decrease the PEP rate and severity.

1 Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) can lead to significant problems. It can be life-threatening, with a mortality rate of up to 30% [1]. Although gallstones and prolonged alcohol use are the most common causes of AP, many different origins may be considered AP etiology, such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) [2]. The latest guideline of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) defines post-endoscopic cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP) as a condition that relates to recently developed or exacerbated abdominal pain combined with increased pancreatic enzymes (three times above normal range), thus lengthening a planned hospital admission or requiring hospitalization after undergoing ERCP [3]. Although the best way to avoid PEP is to prohibit non-essential ERCP, there are medical and endoscopic strategies to prevent and alleviate PEP [4]. Prophylactic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is the cornerstone of PEP prevention according to the ESGE guidelines [4, 5].

Oxidative stress (OS) is considered a major cause of PEP. Bopanna et al. calculated the OS and antioxidant composition of patients with AP and reported that antioxidant concentrations were lower in AP than in non-AP persons [6]. Although some antioxidants, such as allopurinol or beta carotene have not been accompanied in PEP prevention [7, 8], there are some published reports regarding the efficacy of others such as vitamin C and CoQ10 in the prevention or alleviation of PEP [9, 10]. Mesna (2-mercaptoethane sulfonate sodium) is officially approved for the avoidance or alleviation of urothelial damage in persons under treatment with ifosfamide or cyclophosphamide [11]. Antioxidant properties of mesna have been proposed in previous studies [12-14]. Hagar et al. designed an animal study to evaluate the probable effect of mesna on an experimental model of cerulein-induced AP. They reported that mesna alleviates AP by decreasing pancreatic OS damage and preventing inflammation significantly [12]. In a separate animal study, Shusterman et al. demonstrated that the induction of intrinsic nitric oxide, facilitated by mesna, effectively mitigated intestinal inflammation within an experimental colitis model. They posited that mesna likely alleviated this inflammation through the scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROSs) produced by the increased infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes [13]. Sanal et al. examined the effect of mesna administration on systemic injury induced by ischemia/reperfusion in the small intestine and liver, kidney, and lung of rats. They concluded that mesna administration caused recovery in superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase activities but not in histopathologic findings of the mentioned tissues [14].

Given the paucity of data on the role of mesna in preventing or mitigating PEP, this clinical trial sought to evaluate whether the combined administration of mesna and indomethacin is more effective than indomethacin alone in reducing the incidence and severity of PEP (primary outcome). Additionally, the study aimed to assess whether this combination therapy could better control the elevation of pancreatic enzymes following ERCP (secondary outcome).

2 Methods and Patients

2.1 Study Design

The present trial was designed as a prospective, randomized, open-label which was done in the endoscopic procedures ward of Talighani Hospital (a teaching hospital), Tehran, Iran. The trial was registered at the Iranian Clinical Trial Registry (IRCT20121021011192N16) in October 2023. Also, an ethical code has been obtained from the committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1402.341).

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion

We included patients between 18 and 80 years old with any diagnostic or therapeutic indication for ERCP. Participants were excluded if they had a history of allergy to aspirin or NSAIDs, renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min), a requirement for pancreato-biliary stent placement, a past medical history of biliary or pancreatic sphincterotomy, or were pregnant or breastfeeding. After the selection of eligible patients, written informed consent was received from all volunteers. Before undergoing ERCP, each participant provided her/his medical history and blood specimens were collected.

2.3 Intervention and Outcome Measure

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either a 100 mg indomethacin suppository (Behvazan Pharmaceutical Co., Rasht, Iran) combined with a 400 mg mesna injection (Varian Pharmed Pharmaceutical Co., Tehran, Iran) diluted in 100 mL Ringer's solution (Samen Pharmaceutical Co., Mashhad, Iran) or a 100 mg indomethacin suppository alone. Randomization was conducted using a center-based, computer-generated block randomization method. The assigned medications (indomethacin plus mesna or indomethacin alone) were administered 30 min prior to undergoing ERCP, which was performed by three specialized endoscopists, each conducting approximately 400 ERCP procedures annually. All participants were sedated using a combination of midazolam and morphine. Also, all the participants received ringer lactate (2 mL/kg) during the procedure to meet volume needs. Secondary blood samples were obtained from the participants 6 h after ERCP. Participants meeting two components of the Atlanta criteria were diagnosed with PEP: abdominal pain consistent with pancreatitis, elevated amylase or lipase levels exceeding three times the upper limit of normal, and imaging indicative of AP [15]. Diagnosed PEP patients were categorized into three groups: mild, moderate, and severe. Those with no organ failure were classified as mild, those with organ failure lasting more than 48 h as moderate, and those with persistent organ failure or ongoing systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) beyond 48 h as severe [15]. The risk grade for PEP was determined in all patients. High-risk patients were identified as those possessing at least one major risk factor or two minor risk factors for PEP. The major risk factors included sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, a previous history of PEP, difficult or failed cannulation (defined as more than three attempts), pancreatic duct contrast injection, pancreatic sphincterotomy, and precut sphincterotomy. The minor risk factors comprised women, aged below 50 years, normal serum bilirubin levels, normal common bile duct size, and a history of recurrent pancreatitis [4].

2.4 Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 24 (Chicago, Illinois, USA). Numerical variables were presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were expressed as absolute values and frequencies. The means of age, BMI, total bilirubin, amylase, and lipase levels were compared within groups utilizing the paired t-test. For the comparison of categorical data, including ERCP indication, ERCP difficulty, previous history of AP/PEP, and the rate and severity of PEP between the two groups, the chi-square test was employed. Based on a recent trial evaluating the efficacy of vitamin C as an antioxidant in alleviating post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) [9], we employed the formula for two proportions of two independent groups. It was calculated that 698 participants (349 in each group) would be required to detect a 7% difference in PEP occurrence (16% in the indomethacin group vs. 9% in the mesna plus indomethacin group) with a power of 80% and an alpha of 0.05.

3 Results

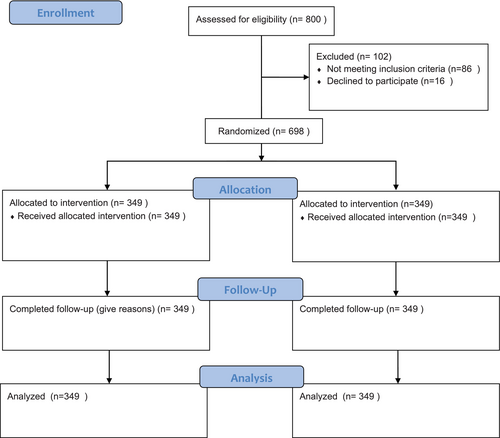

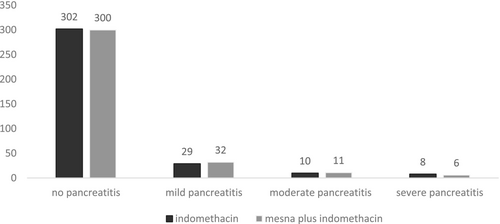

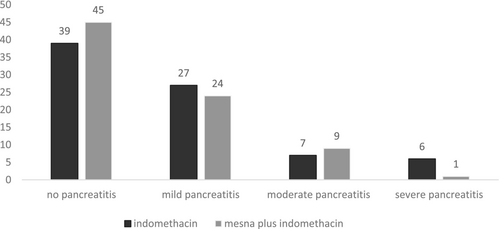

In this study, 698 volunteers completed the trial exactly per protocol from October 2023 to August 2024. The flowchart of the trial is presented in Figure 1. All the volunteers tolerated the medications well in both arms and there was no dropout from the trial due to adverse events. The baseline demographic, biochemical and procedure-related parameters are shown in Table 1. There were no differences between the two arms regarding sex group, age, body mass index (BMI), and biochemical parameters (including bilirubin, amylase, and lipase levels) at the baseline. Also, the two arms were matched regarding procedure-related parameters (ERCP indication, difficulty and history of previous AP/PEP). The total number of PEP was 96 among 698 patients (13.7%). Additionally, it was determined that 14% and 13.7% of evaluated patients were diagnosed with PEP in the mesna plus combined with indomethacin and indomethacin alone arms, respectively. Figure 2 indicates the PEP rate and severity in two arms. Statistical analysis showed that there was no difference between the two groups regarding PEP occurrence and severity (p = 0.671). Moreover, 158 patients out of 698 (22.6%) were classified as high risk for PEP occurrence (79 in the mesna plus indomethacin and 79 in the indomethacin arm). In high-risk patients, the occurrence of PEP was determined in the two groups distinctly (Figure 3). In high-risk patients, our findings showed that the PEP rate (total in mild, moderate, and severe cases) was 41.7% and 51.8% in the mesna plus indomethacin and indomethacin alone group, respectively. Among the mentioned patients, statistical analysis revealed that the difference was significant between the two groups (p = 0.033). The average levels of amylase and lipase 6 h later than doing ERCP (secondary pancreatic enzyme levels) are summarized in Table 2. Secondary pancreatic enzymes increased compared to baseline levels significantly (p = 0.023 for amylase and p = 0.038 for lipase). In between groups analysis, secondary amylase and lipase levels did not differ between the two arms (p = 0.753 and 0.638, respectively). Table 2 shows secondary pancreatic enzymes in high-risk patients. In the analysis of these patients, where the mean level of amylase and lipase were higher in the indomethacin alone arm than in the mesna plus indomethacin arm, there was a significant statistical difference between the two arms regarding secondary amylase level (p = 0.042) and secondary lipase level (p = 0.038).

| Indomethacin plus mesna arm (n = 349) | Indomethacin alone arm (n = 349) | p | Total (n = 698) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (%) | 198 (56.7%) | 204 (58.4%) | 0.89 | 402 (57.6%) |

| Mean age (year) | 58.0 ± 9.3 | 62.8 ± 7.4 | 0.76 | 61.2 ± 8.7 |

| Body mass index | 22.4 ± 1.6 | 24.0 ± 1.4 | 0.83 | 23.4 ± 1.5 |

| Total Bilirubin level (mg/dL) | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 0.68 | 1.8 ± 1.3 |

| Amylase concentration (IU/L) | 58 ± 26 | 63 ± 22 | 0.67 | 61 ± 23 |

| Lipase concentration (IU/L) | 76 ± 20 | 79 ± 24 | 0.57 | 78 ± 19 |

| ERCP indications | ||||

| CBD stone with or without cholangitis | 243 | 245 | 0.78 | 488 |

| Periampulary tumors | 99 | 103 | 202 | |

| Others (mainly cholangiocarcinoma, parasites) | 7 | 1 | 8 | |

| ERCP difficulty | ||||

| 1 | 14 | 14 | 0.89 | 28 |

| 2 | 302 | 316 | 618 | |

| 3 | 21 | 15 | 36 | |

| 4 | 12 | 4 | 16 | |

| No previous history of AP/PEP (%) | 346 (99.1%) | 343 (98.2%) | 0.93 | 689 (98.7%) |

| Level of pancreatic enzymes in all patients | Mesna plus indomethacin group (n = 349) | Indomethacin alone group (n = 349) | p | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase (IU/L) | 265 ± 45 | 279 ± 53 | 0.753 | 270 ± 51 |

| Lipase (IU/L) | 198 ± 29 | 207 ± 32 | 0.638 | 201 ± 31 |

| Level of pancreatic enzymes in high-risk patients | Mesna plus indomethacin group (n = 78) | Indomethacin alone group (n = 78) | p | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase (IU/L) | 307 ± 14 | 396 ± 16 | 0.042 | 356 ± 18 |

| Lipase (IU/L) | 301 ± 7 | 352 ± 9 | 0.038 | 322 ± 11 |

4 Discussion

Although there are so many published papers regarding PEP, the exact mechanism has not been revealed yet [4]. It seems that mechanical damage to the pancreatic acinar cells during ERCP originates from OS process, leading to oxidation of lipids, and proteins and finally disturbance in pancreas histology. Given the role of OS in the pathogenesis of PEP, agents that can relieve it would decrease or attenuate outcomes [9]. In a human study, Shiller et al. evaluated OS biomarkers (such as malondialdehyde, glutathione, C-reactive protein, and fibrinogen) before, 24 and 48 h post-ERCP. Although the low number of patients was mentioned as a limitation in their study, glutathione concentrations decreased after ERCP [16]. In a clinical trial by Abdi et al., 347 patients undergoing ERCP received an indomethacin suppository plus CoQ10 or indomethacin suppository plus an identical placebo 1 h before doing the procedure. They reported that amylase, lipase, and malondialdehyde (as a biomarker of OS) concentrations were lower in the CoQ10 group than in the placebo group after 12 h (p = 0.032, 0.022, and 0.036, respectively) [10]. Mesna is a mini molecule whose sulfhydryl group provides it with the capacity to counteract ROSs involved in the OS process [17]. There are some published reports regarding the anti-OS properties of mesna in the literature. Anti-OS role of mesna has been reported previously in an experimental model of AP [12], colitis [13], and renal injury [17]. For prevention or alleviation of PEP, NSAIDs have been recommended via rectal administration because of their rapid absorption rate compared with oral administration [5]. As mesna could be administered intravenously, it seems that it is a good candidate for evaluation of PEP prevention/alleviation. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first clinical trial to investigate the effects of mesna combined with indomethacin versus indomethacin alone on the rate and severity of PEP. In our trial, both groups were matched for sex, age, ERCP difficulty, and baseline biochemical parameters (amylase, lipase, and bilirubin), ensuring the absence of confounding factors between the two arms.

To assess the efficacy of antioxidant molecules in reducing PEP, they were predominantly compared against a placebo in most clinical studies. Therefore, in a meta-analysis, Goosheh et al. mentioned that antioxidant molecules alone did not play a positive role in PEP reduction [18]. Recently, there have been some published papers regarding the positive effects of antioxidants plus rectal NSAIDs in the alleviation of PEP (combination option) [9, 10, 19]. In this trial, we evaluate the effect of mesna addition (400 mg) to indomethacin versus indomethacin alone on PEP rate and severity too. Some participants in each study group were diagnosed with PEP, with an incidence of 14% in the mesna plus indomethacin group and 13.4% in the indomethacin alone group. Statistical analysis indicated that there were no significant differences in the rate and severity of PEP between the two groups. Also, the combination option (indomethacin and mesna) did not cause any difference in amylase and lipase enzymes among the two groups (p = 0.753, 0.638 respectively).

The only positive finding of our trial was seen in high-risk patients. In these patients, PEP rate and severity were significantly lower in the combination group than in the indomethacin alone group (p = 0.033). To PEP decrease, it seems that mesna addition to indomethacin is only rational in high-risk patients. Similar to our results, there are reports that some pharmacologic agents alleviate PEP rate and severity in only high-risk patients. Aletaha et al. evaluated the administration of intravenous magnesium sulfate (2 g) or placebo plus indomethacin 1 h before ERCP for alleviation of PEP. Although magnesium administration did not reduce the overall rate of PEP in all patients, it significantly decreased the incidence of PEP among high-risk participants in the intervention group compared to the placebo group (p = 0.017) [20].

A serum amylase level four to five times above the upper normal range during 3–6 h after ERCP, along with the presence of clinical findings of AP, has been accepted for diagnosis of PEP. We measured the serum amylase 6 h after doing the procedure in our trial (secondary amylase). In all patients, we observed no difference between secondary amylase levels among mesna and placebo arm (p = 0.753). The same findings were observed for the secondary lipase in our study; there was no significant difference between the two arms (p = 0.638). When we only analyzed the high-risk patients, a significant difference was seen between levels of both amylase and lipase in the indomethacin versus mesna plus indomethacin group. According to our results, it seems that a combination of indomethacin and mesna may be effective in controlling the amylase and lipase elevation compared to indomethacin alone in high-risk patients.

Compared to conclusions from other trials indicating an incidence of PEP in high-risk patients at approximately 17%–40% [15], our study reveals comparable results for patients in the placebo group, while significantly fewer cases of PEP were observed in the mesna group. The rate of PEP was high in our trial specially in high-risk patients. The trial was conducted in a teaching hospital, where ERCP procedures were performed by gastroenterology fellows under the supervision of attending physicians. Several studies have investigated whether the involvement of trainees in ERCPs may elevate the risk of PEP [4]. There is a paucity of data regarding the efficacy of mesna in the alleviation of PEP. Therefore, making a precise comparison with results from other human trials is not feasible. The design of the trial as placebo-controlled and the use of excessive amounts of mesna were considered trial limitations. There is no dropout of participants due to adverse drug reactions in our trial and higher doses of mesna may significantly reduce the PEP rate and severity in all patients (in all patients).

Regarding the probable mechanism of mesna in the prevention or alleviation of PEP, assessment of the inflammatory biomarkers responsible for PEP, such as malondialdehyde and glutathione peroxidase, is strongly suggested for future studies. Given that the trial was not designed to assess the efficacy of mesna in the high-risk group, the conclusion regarding its effectiveness in this subgroup should be considered exploratory. It is suggested that mesna may be effective; however, further confirmatory trials are necessary to substantiate this finding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would thank to Varian Pharmed Pharmaceutical company because of their donation of mesna vials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.