Lymphocytic esophagitis: An Australian (Queensland) case series of a newly recognized mimic of eosinophilic esophagitis

Abstract

Background and Aim

Lymphocytic esophagitis (LoE) is a recently described upper gastrointestinal tract “disorder” diagnosis of which hinges on histology and is characterized by the excessive infiltration of lymphocytes in the peripapillary fields of the esophageal epithelium, with clinical manifestations similar to those of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). In this article, we aim to describe for the first time the clinico-pathological characteristics of a large cohort of Australian (Queensland) cases of LoE.

Methods

Histological data that fulfilled the criteria (predominant lymphocytic infiltration in the peripapillary fields, none or minimal neutrophils or eosinophils, and no infection) were collected between January 2014 and May 2016 from a number of major Queensland Public Hospital anatomical pathology laboratories. Patient presentations were subsequently examined to compile clinical and endoscopic correlates.

Results

A total of 62 cases of LoE were identified. The median age was 55 years, with 59.6% of subjects being male. Major clinical manifestations included dysphagia (32), epigastric or abdominal pain (8), gastro-esophageal reflux (8), association with Crohn's disease (8), and vomiting or diarrhea (6). Endoscopy was normal in 47% of cases; 47% had appearances similar to those of EoE. There were three cases with associated mild monilial esophagitis (6%).

Conclusion

LoE is a relatively recently recognized condition of the esophagus with variable clinical and endoscopic findings. Diagnosis is based on characteristic histological features. Further investigation is needed to ascertain the etiopathology and natural history of the condition and to establish a safe and effective treatment regimen.

The index case

A 67-year-old male patient presented to a Brisbane public hospital outpatient department with a 3-month history of progressive dysphagia and odynophagia with 5–7 kg of weight loss. His past medical history was significant for alcohol dependence (150 g daily consumption), heavy smoking of 40 cigarettes per day, chronic calcific pancreatitis (with a benign mass on endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of the uncinate process), impaired glucose tolerance, hypertension, and fistula-in-ano (now healed). His regular medications included Fenofibrate, Omeprazole (started after the patient complained of some dysphagia a month ago), and Irbesartan.

This presentation was investigated initially with a barium swallow, which did not demonstrate any significant abnormality. Blood tests including a full blood count, liver functions tests, anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody (anti-tTG), anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (anti-dsDNA), C-reactive protein (CRP), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and tumors markers [carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), prostate specific antigen (PSA)] were all normal, apart from an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at twice the upper limit of normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated at 30 mm/h.

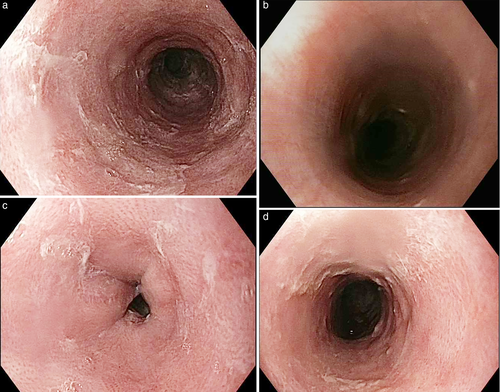

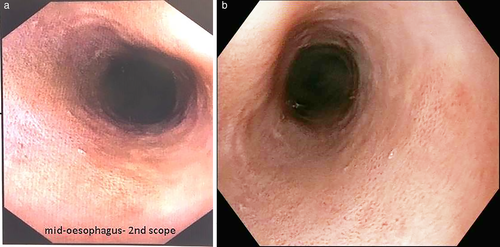

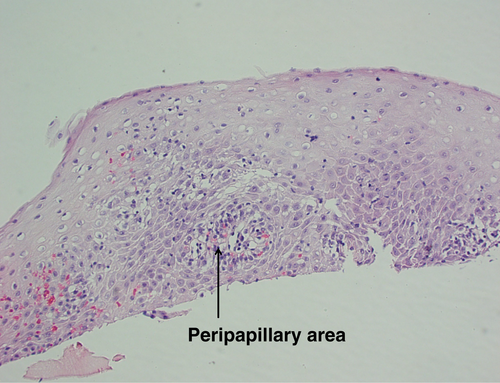

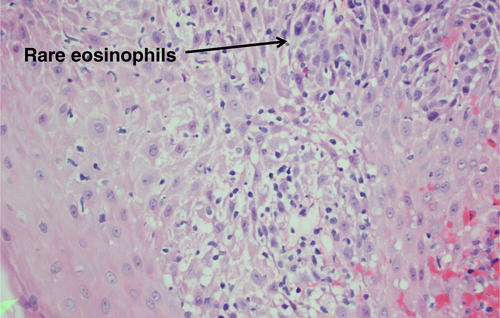

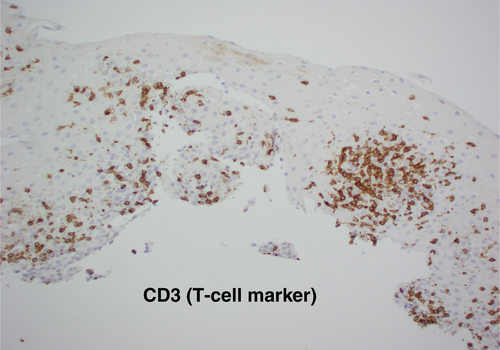

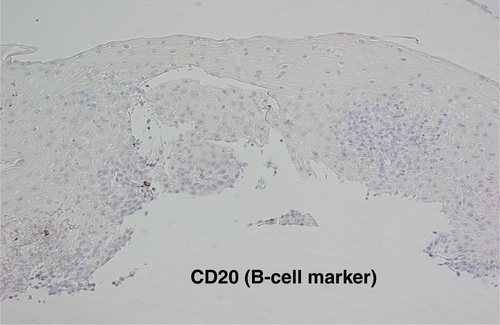

Gastroscopy demonstrated a uniformly red, rather featureless, esophageal mucosa with a few fluffy white exudates, with infrequent esophageal contraction waves (see Fig. 1). Endoscopically, this could be suggestive of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) or mild candida esophagitis. Gastric and duodenal biopsies showed mild inflammation but no lymphocytic predominance (Fig. 2). Four quadrant biopsies were taken from the upper (at 20 cm) and mid-esophagus (28–30 cm), and the cardia was located at 40 cm. Histopathology (shown in Fig. 3) showed submucosal extensive peripapillary intraepithelial infiltration with lymphocytes. There were 80 and 50 lymphocytes per high power field (HPF) in the upper and mid-esophageal samples, respectively, with rare neutrophils and eosinophils (Fig. 4). Further staining showed that these were CD3-positive T-cells and not B-cells (Figs 5 and 6). Viral inclusion, dysplastic, and neoplastic processes were looked for but not found.

The patient was commenced on oral Fluticasone (two puffs BD (twice daily), 50 mcg/puff) after meals and Rabeprazole before meals (20 mg BD, changed from Omeprazole 20 mg daily). There was symptomatic improvement, but the patient discontinued the medications after 3 months of use as his symptoms resolved.

A repeat gastroscopy was performed 6 months following the initial diagnosis; there was mild erythema of the esophageal mucosa, and it looked like a noncontractile flaccid bag (Fig. 2). Biopsies were taken from the upper, mid, and lower esophagus. Histopathology from the mid-esophagus showed increased lymphocytic infiltration with marked reactive changes with basal edema and hyperplasia, with lengthening of the papillae. Clinically, the previously reported dysphagia had improved.

Discussion

Lymphocytic esophagitis (LoE) is an upper gastrointestinal tract disorder first described by Rubio et al. in 2006.1 The condition has varied clinical presentations and is histologically characterized by excessive infiltration of lymphocytes in the peripapillary fields of the esophageal epithelium.1 Subsequently, a larger series was published in 2012 by Haque and Genta, where they identified 119 cases of LoE.2 The most common clinical presentations of LoE were dysphagia, dyspepsia, and chest pain.1-3 Data collected from a large gastrointestinal pathology practice in the United States found that, overall, histological features of LoE were present in 0.1% of esophageal biopsies.2 The first Australian case report was published in 2012, where the patient presented with spontaneous rupture of the esophagus.4

In this report, the demographic data and clinical presentations of 62 patients from Queensland, Australia is presented (Tables 1 and 2). The IRB approved the study on 4/9/15 with the following ref. no: HREC/15/QPAH/602. The data were collected between January 2014 and May 2016 from the bulk of Queensland public pathology laboratories, which cover an estimated 30% of gastrointestinal biopsies in the state. For the full year of 2014, there were 36 cases of LoE out of a total of 8239 esophageal biopsies processed, giving a prevalence rate of 0.27%. Most studies seem to indicate that the number of new cases diagnosed each year is increasing. One large series from the United States, performed in 2012, found the rate to be 0.10% of the total esophageal biopsies.2

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Total number | 62 |

| Median age (age range) | 55 (1–85 years) |

| Men | 37 (60%) |

| Major clinical manifestations | |

| Dysphagia | 32 (51%) |

| Epigastric/abdominal pain | 8 (13%) |

| GERD | 8 (13%) |

| Associated with Crohn's disease | 8 (13%) |

- GERD, Gastro-esophageal reflux disease.

| Endoscopic appearance | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Normal esophagus | 29 | 47 |

| Esophagitis | 9 | 15 |

| Stricture | 7 | 11 |

| Esophageal rings/linear furrows/EoE like | 13 | 21 |

| Monilial infection | 4 | 6 |

- EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis.

Reports suggest that dysphagia, chest pain and reflux are the most frequent symptoms of patients diagnosed with LoE.1-4 This is confirmed in our cohort of 62 patients, where 51% presented with dysphagia (32), 13% with GERD/abdominal pain/epigastric pain (8), 13% associated with Crohn's disease (8), and 10% with vomiting/diarrhea/failure to thrive (6). To clarify the significance of these nonspecific symptoms, Purdy et al. completed a study comparing 42 patients with LoE to 34 patients with esophageal biopsies for other reasons.5 It was found that there was no significant difference in the symptoms or endoscopic appearance between the two groups.5 There was, however, a trend toward a higher rate of associated Crohn's disease in patients with LoE (12% compared to 4%), but this was not statistically significant.5 In our case series, six of the eight patients with both LoE and Crohn's disease were from the pediatric population (age < 16 years). This further confirms the previously demonstrated association between LoE and Crohn's disease in children.6

A large proportion of patients who are diagnosed with LoE on the basis of histology have a normal-appearing esophageal mucosa at endoscopy.3, 5 Of the 62 cases of LoE in our case series, 47% had a normal-appearing esophagus (29/62) on white light endoscopy; 29 patients (47%) had an appearance not dissimilar to EoE, with either rings and furrows, strictures or esophagitis, while 4 cases (6%) had monilial elements on histology (Table 2).

Previous studies have also found that, in some cases, endoscopic appearance can be very similar to that of EoE with edema, esophageal mucosal rings and linear furrows, and strictures.2, 7 Given the prevalence of normal-appearing mucosa on endoscopy, further image-enhancing technology, such as narrow-band imaging (NBI), has been explored to aid in the diagnosis of both LoE and EoE.8 Tanaka et al. found three characteristics on NBI that would suggest these diagnoses; first, beige color of mucosa on NBI, where a normal esophageal mucosa would appear light green8; second, increased and congested intrapapillary loops; and finally, a lack of visible submucosal vessels.8

The diagnosis of LoE hinges on histology. Three histological characteristics are recognized to be the cornerstone of diagnosis: (1) peripapillary lymphocytosis, (2) marked spongiosis or intercellular edema, and (3) with little or no neutrophils or eosinophils with absence of infectious etiologies.2 These histological features are captured in Figures 3 and 4. Initial attempts to determine a threshold for lymphocyte numbers have been thwarted by the observation that areas of lymphocytic infiltration were in a patchy distribution, and hence, it was concluded that the pattern of distribution and coexistence with spongiosis were more important than the absolute number of lymphocytes.2 Intraepithelial lymphocytes are T-cells and not B-cells (CD3 + ve, CD4 > CD8) as demonstrated in Figures 5 and 6, respectively, taken from our index case.

There is a lack of an evidence-based guideline regarding treatment of this condition. Anecdotally, patients report symptomatic improvement with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), but it remains unclear whether this improvement is due to treatment of reflux associated with LoE or whether there is a sub-population of PPI-responsive LoE patients.3 Topical steroid therapy, similar to that used in the treatment of EoE, is also believed to be of benefit, but this has not been investigated in a clinical trial setting. Most patients note symptomatic improvement with PPI alone.3 However, in the subset of patients presenting with esophageal strictures, repeated dilatations were needed in addition to the above medical therapy.5, 9 In more benign cases, spontaneous resolution of the histological abnormalities has been noted. In 2016, Weltman et al. from Australia (NSW) described three adult patients aged 51, 59, and 85 years, presenting with dysphagia. One resolved spontaneously, and another showed minimal symptomatic relief with PPI and topical steroids, while the third patient needed repeat dilatation over the years, despite maximized medical therapy.9 LoE has recently been associated with primary oesophageal motility disorder. In the study by Xue et al., primary esophageal dysmotility, observed in esophageal manometry or barium swallow, was found in 91% (10/11) of the patients with no granulocytes and in 61% of those with a few granulocytes on histology. In studies where lymphocyte subsets were analyzed, the incidence of primary esophageal dysmotility was significantly higher in patients with CD4-predominant esophagitis than in patients with CD8-predominant esophagitis.10 Obviously, further studies are required to characterize this possibly distinct clinicopathological entity.

The natural history of LoE was assessed by Cohen et al., who found it to be a relatively benign disease in a group of 29 patients who had long-term follow-up.3 While treating them with a PPI, the highest rate of symptomatic improvement was seen in those with dysphagia and the lowest in those with chest pain. In a limited number of patients who had follow-up biopsies, histological normalization was observed in 9 of 22 cases, indicating that histological changes can potentially normalize in about half the patients, however; the number of patients in this study was small.5 Some authors found that the risk factors for LoE were elderly females (63%) and history of current or past smoking (55%),11 while we did not find the same (60% of our patients were male), possibly due to the high number of male (eight males, five females) pediatric patients in our series. There was no relationship with BMI or use of NSAID or PPI. Thus, to date, LoE remains a “disease” with no established definition or clinical associations.11

Conclusion

Despite paucity of reports from Australia (only 4 cases4, 9 in 2012 and 2016), our large case series now establishes LoE to be a significant pathology here with prevalence similar to other parts of the world and thus would be begging to be recognized and dealt with appropriately. LoE is an increasingly recognized disorder although it is difficult to diagnose due to the nonspecific clinical presentation and the patchy nature of the esophageal lymphocytic infiltrate on biopsy.3 This is all the more compounded by a lack of awareness of the disease in the medical community. Most studies indicate it to be a rather benign illness with spontaneous recovery in about half the cases. However, stricture needing repeat dilatation can sometimes be encountered, and it is touted as a potential cause for primary esophageal motility disorder. A majority of our cases (except the index case) were not investigated with barium swallow or manometry. Diagnostic advances, such as NBI-guided biopsy of esophageal mucosa, are likely to assist in improving the yield of biopsies and therefore identify patients suitable for therapy. In spite of the fact that proton pump inhibitors (PPI) are initially effective in most, further investigation into the role of dietary exclusion and topical steroid therapy is needed to treat those who are resistant to first-line treatment and to establish a regimen that would be safe and effective on a long-term basis.