Unveiling genetic counseling skills: Developing an online training course and analyzing counselor communication practices

Abstract

Despite the pivotal role of communication skills in genetic counseling, communication strategies employed by genetic counselors in their current practice remain largely unexplored. The field of genetic counseling could benefit from updated simulated genetic counseling sessions conducted by genetic counselors illustrating a diversity of skills. This paper outlines the development and evaluation of updated simulations used to develop an online training course to identify genetic counseling skills and to assess how commonly these skills are used. Practicing genetic counselors in the United States were recruited to counsel trained standardized patients across six pretest and posttest simulated sessions in cancer, prenatal, and cardiology genetics settings. Sessions were coded using the novel Genetic Counseling Skills Checklist to identify which communication and counseling skills were utilized. Standardized patients were asked to provide session quality ratings and written feedback, which were analyzed using descriptive statistics and content analysis, respectively. Results from 64 recorded sessions involving 20 counselors from a variety of training programs, racial and ethnic backgrounds, states of residence, and with varying years of clinical experience revealed utilization of a broad array of skills across specialty types and clinical indications. The total number of unique skills used varied widely from 12 to 49, with an average of 35.8 out of 56 possible skills checked per session. Differences in skill usage were observed between pretest and posttest sessions. Standardized patient comments were predominantly positive with a focus on information delivery and empathetic responses. Perceptions of areas of improvement were giving less information, having clearer delivery, and expressing more empathy. This work led to the creation of a training course showcasing various skills used by practicing genetic counselors, which summarizes commonly used skills and other promising but less frequently utilized ones.

What is known about this topic:

Genetic counselors report using many different communication and counseling skills to achieve session goals. However, the range of skills that practicing genetic counselors currently use is not well characterized, and training modules to recognize the variety of skills genetic counselors report using are limited.

What this paper adds to the topic:

We identify the genetic counseling skills commonly and rarely used by a diverse group of genetic counselors. Additionally, we describe an associated online training course that was developed to help identify skills contained within the genetic counseling skills checklist.

1 INTRODUCTION

Genetic counselors report using many different communication and counseling skills to achieve a variety of session goals (Zale et al., 2022). Genetic counseling skills are taught in training programs through the incorporation of readings from textbooks, role plays, simulated patient sessions, and live supervision in fieldwork rotations (Lowe & Roter, 2023; Veach et al., 2018; Wherley et al., 2015). Continuing education on counseling skills is predominantly didactic, and there are few opportunities to assess counselors' skills following graduation from master's programs (ABGC CEU Standards, 2024). Limited opportunities for supervision while practicing and a lack of recordings from actual genetic counseling sessions have led to a field in which little is known about what skills are routinely used, how counselors create a strategy for implementing the skills, and what constitutes routine practice.

Simulated cases performed by trained standardized participants or patients (SPs) are a means of assisting in skills development, assessment, and research (Flanagan & Cummings, 2023; Lowe & Roter, 2023; Ma et al., 2023). SPs are individuals purposefully coached to engage with learners in simulated encounters through role-playing, providing constructive feedback, and/or assessing learners (Gliva-McConvey et al., 2020). Collecting data on healthcare encounters in a standardized setting with SPs is beneficial because SPs may be coached to provide consistent role portrayals and feedback from the patient perspective (Lewis et al., 2017). SPs also provide valuable insights into their experiences across practitioners (Flanagan & Cummings, 2023). Recordings of simulated sessions can be collected without identifying healthcare information to allow for more easily disseminated audio recordings or videos for teaching and research purposes. One such vital resource for the genetic counseling field was the genetic counseling video project that collected 152 recordings from 177 genetic counselors' simulated sessions, which formed the foundation of research on genetic counseling skills and styles (Roter et al., 2006). The genetic counseling video project was a useful dataset for years, but the field of genetic counseling has changed significantly over the past 20 years. Given the time that has passed, there is a great need for more health communication-related research and updated simulated genetic counseling sessions with racially and ethnically diverse SPs and counselors (Shete et al., 2023). Furthermore, greater inclusivity of gender and sexual orientation diversity, encompassing different clinical specialty types and case scenarios, could provide more inclusive resources for prospective students and for genetic counseling students in training (O'Sullivan et al., 2023).

As research continues to assess the genetic counseling process, it should explore whether genetic counselors' skills vary depending on their aims and the specific goals set by patients (Veach et al., 2007). Strategies that counselors may utilize have been outlined and elaborated on in the reciprocal engagement model of practice, the Framework for Outcomes in Clinical Communication Services, and from analyses of counselor-described successful and unsuccessful sessions (Cragun & Zierhut, 2018; Redlinger-Grosse et al., 2017; Veach et al., 2007). Examples of skills utilized by genetic counselors may include checking patient's existing knowledge, summarizing information, using diagrams or visuals to explain genetics, or inviting the patient to interrupt or stop the genetic counselor with questions (Cragun & Zierhut, 2018; Lobb et al., 2005; Redlinger-Grosse et al., 2017; Veach et al., 2007).

The Genetic Counseling Skills Checklist (GCSC) is a novel process measure that builds upon work from other fields and is designed to document skills genetic counselors use and have self-described to achieve session goals (Hehmeyer et al., 2023; Zale et al., 2022). The GCSC is a pragmatic tool whereby third-party observers, sometimes called coders, identify communication skills employed across the entirety of the genetic counseling session, and it can be completed within the length of the session (i.e., real time). The GCSC organizes skills into eight broad communication skills categories (described further in Section 2), each containing four to eight skills (Hehmeyer et al., 2023). The GCSC was designed for use across clinical specialties and counselor practice styles as a way of comparing which skills are used by genetic counselors across different session types or indications.

The GCSC holds potential value for future research on genetic counseling processes. However, before it can be implemented into different studies, there needs to be a training module accompanying the checklist to ensure coders can easily receive proper training and can achieve high reliability of checklist coding. This would also necessitate updated genetic counseling simulated cases and/or real-life counseling sessions to use for training examples. The target audience for GCSC training and skills identification could range from experienced genetic counselors and researchers to undergraduate students. An online format is desirable because it allows for widespread distribution, making it accessible to a larger audience. This accessibility facilitates the use of the instrument in various settings, such as education that could be used by training program directors or clinical genetic counselors, improving its overall utility and impact.

The following study describes the creation of a novel training course demonstrating genetic counseling skills defined by the GCSC and identifying which skills are used across genetic counseling sessions. The first aim of this study was to create an updated series of cancer, prenatal, and cardiology videos of SP sessions and to incorporate them into an online training course that can teach individuals with no prior exposure to genetic counseling to recognize genetic counseling communication skills and reliably use the GCSC. Our second aim was to use the SP sessions and the GCSC to identify which skills are commonly or uncommonly used by a diverse sample of genetic counselors. This work lends greater understanding of currently used skills and resulted in a training course demonstrating a variety of skills, including those that are consistently used and other potentially beneficial skills that are less commonly used.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants and recruitment

This study received approval through the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board as part of the Genetic Counseling Skills Checklist Utilization and Creation of Resource Repository study (#00012065). Authors of this study declare no conflicts of interest. An invitation to participate in the study was sent via a National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) research email, NSGC special interest group announcements, and social media posts on X (formerly Twitter) to recruit clinical genetic counselors in the United States. Interested genetic counselors completed a screening questionnaire. To be eligible for participation, genetic counselors had to indicate that they worked in either a cancer, prenatal, or cardiology clinical setting and were American Board of Genetic Counseling board certified or board eligible. A total of 71 genetic counselors responded to the invitation, and 52 met inclusion criteria. Genetic counseling participants (n = 18) were then purposefully selected based on their practicing specialty (six prenatal, six cancer, and six cardiology) and variation in years of experience, location of practice, graduate training program, and demographic data to ensure a diversity of genetic counselor backgrounds. The initial goal was that the counselors from each specialty would counsel a pretest and posttest session for the same two case scenarios (e.g., cancer patient #1 pretest, cancer patient #1 posttest; cancer patient #2 pretest, cancer patient #2 posttest) for a total of 72 sessions.

Over the course of three separate days in July 2021, online genetic counseling sessions (utilizing SPs) were recorded in three different clinical specialties (e.g., prenatal, cancer, and cardiology). These specialties were chosen to represent two of the most common areas of practice (prenatal and cancer) and one growing specialty area (cardiology) in which counselors typically complete entire sessions independent of a medical geneticist. Genetic counselors were asked to sign up for one of the dates and counsel both a pretest and a posttest simulated session for both clinical indications within their specialty. However, two of the cardiology genetic counselors preferred to only counsel one case and were paired to cover the two cases. A week before the sessions occurred, the genetic counselors were given written background information about the clinical scenarios and the patient (Data S1). They were then instructed to counsel the cases as they typically would in their practice, including using any visual or decision aids in alignment with their typical practice. Due to last-minute clinic-related matters, three genetic counselors canceled and were replaced with other genetic counselor participants. One prenatal genetic counselor was not able to be replaced by an alternate, and four genetic counselors served as alternates for the two cardiology genetic counselors (each completing one of the two patient cases). SPs were recruited through M Simulation at the University of Minnesota. M Simulation is a department that provides 40,000 annual learner contact hours of healthcare simulation training across three campuses. The M Simulation team also designs and delivers simulated training that supports research experiences in the health sciences. The SPs were selected by SP educators on the M Simulation team to align with the identity dimensions outlined in the case scenarios. All SPs were at least 18 years of age and fluent in English.

2.2 Instrumentation and procedures

2.2.1 Simulated genetic counseling cases

Six simulated genetic counseling cases were created for the indications of breast cancer, colon cancer, preconception carrier screening, noninvasive prenatal testing, familial hypercholesterolemia, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Case development was an iterative process that included in-person meetings and feedback on case scenarios with a genetic counseling graduate student and two genetic counseling researchers over several months in 2021. The six cases were reviewed in an online training by the SP educators, SPs, and a third genetic counseling researcher to add clarity, refine details, and include additional acting prompts. All of the cases consisted of two genetic counseling sessions, with one occurring before genetic testing (pretest) and another after genetic testing (posttest). Online simulated sessions were scheduled for a 45-min pretest session and a 30 min posttest session. The final cases are available in the Data S2. SPs were each trained to act for one of six specified cases.

2.2.2 Genetic counseling skills checklist procedures

The multistage iterative process used to develop and pilot the GCSC has been previously described (Hehmeyer et al., 2023). The GCSC consists of 56 individual communication skills genetic counselors use (“GCSC,”, 2024). The skills are organized into eight overarching categories: Building Rapport, Mutual Agenda Setting and Session Structuring, Risk Communication, Recognizing and Responding to Emotions and Prior Experiences, Educating, Checking for Understanding, Facilitating Decision-Making, and Promoting Patient Activation. Each category has 5–8 skills. The Risk Communication and Decision-Making categories each have two columns that can capture skills from conversations about two types of risks or two different decisions. When two risks and/or two decisions were coded, the two columns in the respective category were averaged in order to keep the total number of skills possible in each session at 56.

As previously described, GCSC training used the SP videos developed for the course and a series of synchronous, remote, iterative meetings to review and establish consensus (Hehmeyer et al., 2023). Coders watched the recorded SP sessions and coded the checklist in real time using time stamps to identify when specific skills were used. When a coder observed a counselor completing a skill on the GCSC, the skill was marked as completed. Skills not used during the session or not meeting the skill requirements, as indicated on the GCSC, were left blank to denote the skill was not completed or used during the counseling session. After independently coding, each pair of coders discussed and reconciled any coding discrepancies. Consensus discussions involved reviewing relevant (time-stamped) sections of the recordings when needed and completing a final consensus checklist.

2.2.3 GCSC training course development

The primary GC researchers (HZ, DLC) and coding team members (MV, TS, MC, and DC) were consulted on the training course development, and a genetic counseling graduate student (NK) applied findings learned from the training of the SP session coders when leading the development of an online GCSC training course within the Learning Management System, Canvas (GCSC Training, 2024). NK, in collaboration with an academic technology coordinator (KB), built the course outline, webpages, and assessments. Through a series of discussions, the researchers, coding team, and developers reviewed each of the categories and item descriptions collectively and proposed edits to the definitions based on the developers' intentions and the coders' previous experiences applying the definitions to skills while coding sessions. After skill descriptions were finalized, “skills checks” were created to train coders to recognize the skills and understand the criteria for checking each skill item as well as any criteria that would indicate it should not be checked. Skills checks either involved multiple-choice questions about the application of the skills and/or involved two illustrative videos created by pulling examples of skills being employed or not employed within a session from the series of simulated genetic counseling sessions described above. Once the desired video clips were identified, ScreenPal recording software was used to splice clips together with voiceovers explaining the rationale behind why the skill would have been checked as completed or not. Initial drafts of questions used for skills checks and category quizzes were reviewed with the team to ensure accuracy and improve clarity. Suggested edits were incorporated into a finalized set of questions that were agreed upon by the team. The final evaluation test must be completed for a certificate and involves coding at least two full genetic counseling sessions with at least 80% accuracy as compared to the experienced coders' consensus checklists for each session.

The training course was reviewed by a genetic counseling researcher, an academic technology coordinator, and an education professor to provide feedback on the usability of the training course (e.g., flow, readability, and assessments). After edits were made, a practicing genetic counselor piloted the course and provided additional detailed feedback on its usability and clarity of item descriptions, skill checks, and category quizzes. Once another round of revisions was complete, three undergraduate students, who were end users being trained as research assistants for a future study, piloted the entire online course.

2.2.4 SP overall quality ratings and comments

As is typical and per their training, SPs were asked to give overall feedback in the form of written documentation at the end of each session. They were specifically asked to comment on what was helpful and what was not helpful in the session and to give the genetic counseling session a subjective numerical rating (1–10) based on their overall impression. In the prenatal carrier screening case, both SPs who were part of the same session (representing a reproductive couple) rated the session independently, after which their numerical ratings were averaged and comments were consolidated to represent each session.

2.2.5 Third-party coder overall quality ratings

Session coders also independently gave each video a subjective rating (1–10) based on their overall impression of the quality of the genetic counseling. These were then averaged across the two raters to create a third-party quality rating for each session.

2.3 Data analysis

2.3.1 Simulated session genetic counselor participants

To demonstrate variability, counts were conducted to characterize the demographics and prior training of the genetic counselors who completed the simulated sessions.

2.3.2 Genetic counseling skills consensus checklists

Descriptives were calculated to characterize diversity in skills used across the genetic counselors who participated. To summarize the variety of skills employed by genetic counselors, the number of different GCSC skills used in each session was totaled, and the mean and range for all sessions were calculated. The percentages of sessions that utilized each GCSC skill item were calculated and compared across specialties (cancer, prenatal, and cardiology) to assess for general patterns of use. Differences in observed use of skills across pretest versus posttest sessions were assessed by ordering all GCSC skills items according to the percentage of pretest and posttest sessions in which each skill was used. Based upon natural breakpoints in the data, a greater than 90% cut-point was chosen to identify skills commonly used in sessions, and less than 30% was chosen as the cut-point to identify uncommonly used skills.

2.3.3 Overall quality ratings and comments

Means and ranges were calculated for subjective quality ratings from the SPs and third-party raters (e.g., coders). SPs' open-ended responses regarding the quality of the session were analyzed using content analysis. One author (DLC) reviewed all written remarks and organized them through an iterative inductive process that involved the grouping of similar comments (or portions of comments) into categories, developing category labels to represent the content within each category, and collapsing or separating initial categories (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Each categorized comment or partial comment was then reviewed by a second researcher (HZ) and examined to ensure the content reflected each positive and constructive category. Finally, category labels were modified slightly based on discussions between DC and HZ to more accurately describe the underlying theme of each category. The number and percentage of sessions in which each categorical theme was noted were calculated for sessions where SP ratings were 9 or 10 and separately for sessions with SP ratings of 8 or less because the overall ratings were considerably high. Exemplary quotes for each positive and constructive theme were selected. Finally, to further assess for differences in SPs' perceptions of information, an extended analysis of the “valued information provided” theme was completed by reviewing the surrounding text of the quotes categorized in that theme and determining from the context whether SPs related the information to other statements that were categorized into the “empowering or activating” theme and to determine whether those who commented on valuing or learning from information also included a comment categorized in the “too much information” theme.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Simulated genetic counseling cases

Of the 68 recorded sessions, 24 cardiology, 20 prenatal, and 20 cancer sessions were of sufficient quality to be coded and included in the online learning course and analysis of skills used during the sessions. The audio failed on four cancer videos, and these were therefore not included in the analysis. A total of 20 genetic counselors participated (cardiology n = 9; oncology n = 6; and prenatal n = 5) in one or more of the 64 sessions. Of those counselors, 16 identified as female, three identified as male, and one did not select a gender. Races/ethnicities represented by the participants' self-identified categories included White (n = 10), African American (n = 2), Ashkenazi Jewish (n = 1), Asian and White (n = 1), Filipina (n = 1), Latino/a (n = 1), and South Asian (n = 1). Three participants chose not to disclose their race/ethnicity. On average, participants had 6.05 years of clinical experience (range = 1–20 years). Genetic counselors practiced in 13 U.S. states, including Texas (n = 3), Minnesota (n = 3), California (n = 2); Florida (n = 2), Illinois (n = 1), Iowa (n = 1), Massachusetts (n = 1), New York (n = 1), Ohio (n = 1), Oklahoma (n = 1), Tennessee (n = 1), Utah (n = 1), Virginia (n = 1), and one did not respond. Participants' genetic counseling training programs included: University of Minnesota (n = 4), Johns Hopkins University/National Human Genome Research Institute (n = 2), Northwestern University (n = 2), Stanford University (n = 2), University of Cincinnati (n = 1), Howard University (n = 1), Indiana University (n = 1), Mt. Sinai School of Medicine (n = 1), Rutgers University (n = 1), University of Texas (n = 2), University of Utah (n = 1), Wayne State University (n = 1), and one did not provide a response.

3.2 GCSC training course

The online training course was completed in May 2023 and included four sections: an Introduction (overview of the practice of genetic counseling and use of the GCSC), GCSC Categories (skills item detailed descriptions, skills checks, category quiz), Practice Cases (three full session coding examples with feedback), and Final Assessment (nine full sessions to be coded and graded for reliable use of the tool). Additionally, copies of the GCSC in both a printable and interactive PDF version were available for download.

Three undergraduate research assistants (learners) piloted the course. Each learner completed the Introduction and then progressed to the GCSC Category sections, which included the skill checks and category quizzes. Once all category sections were completed, three different simulated genetic counseling practice sessions were unlocked to help the learners gain experience using the entire checklist in one sitting. These practice cases provided learners with detailed feedback on items to improve coding accuracy. All three practice cases were completed before learners moved to the final assessment. For the final assessment, learners filled out the entire GCSC for each of the nine simulated sessions. Learners had only one attempt to code each of the nine genetic counseling sessions with 80% accuracy before advancing to the next session. For future iterations of the course, learners who receive an 80% or greater on two of the nine genetic counseling sessions will be awarded a certificate of completion (and not be required to complete all 9). If learners do not score an 80% or greater on two of the nine sessions, they will not receive the certificate and would need to retake the training course.

3.3 Genetic counseling skills consensus checklists

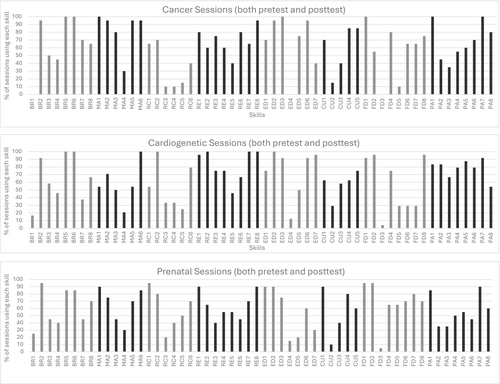

The total number of unique skills used in each session varied widely from 12 to 49, with an average of 35.8 out of 56 possible GCSC skills checked per session. Notably, genetic counselors in all specialties used a variety of skills, with patterns revealing more similarities than differences across specialties/cases (Figure 1). Frequencies of skills used in pretest sessions, posttest sessions, and all sessions combined are included in Data S3. GCSC skills that were almost always used (i.e., observed in 90% or more of the sessions) in both pretest and posttest sessions included “showing respect,” “using active listening skills,” “maintaining an affect that matches the patient's emotions or is suitable to the situation,” “tailoring information,” and “listing or ensuring the patient is aware of medically appropriate options or actions that can be taken.” The other 11 most used skills tended to vary depending on whether the session was a pretest versus a posttest (Table 1). In contrast, skills used in 30% or fewer sessions tended to be used infrequently in both pretest and posttest (Table 2).

| Skills organized by GCSC categories | Pretest sessions | Posttest sessions |

|---|---|---|

| Building rapport | ||

| Greet patient/family (BR2) | √ | |

| Show respect (BR5) | √ | √ |

| Employ active listening skills (BR6) | √ | √ |

| Mutual agenda setting & session structuring | ||

| Establish mutual understanding of reason(s) for visit (MA1) | √ | |

| Elicit patient's agenda/goals (MA2) | √ | |

| Follow-through with most key agenda items (MA5) | √ | |

| Assess and address patient needs throughout with flexibility in prioritizing patient's needs (MA6) | √ | |

| Recognizing and responding to emotions and prior experiences | ||

| Invite patient to share prior experiences (RE1) | √ | |

| Maintain affect that matches patient's emotions or is suitable to situation (RE8) | √ | √ |

| Educating | ||

| Tailor information to patient's needs/wishes/goals/culture/situation (ED2) | √ | √ |

| Simplify information to reduce cognitive load (ED3) | √ | |

| Facilitating decision-making | ||

| List or ensure patient is aware of medically appropriate options or actions that can be taken (FD1) | √ | √ |

| Explore potential outcomes of options (FD2) | √ | |

| Promoting patient activation | ||

| Detail and summarize an action plan of next step(s) (PA1) | √ | |

| Provide support resources and/or referrals (PA6) | √ | |

| Obtain agreement/commitment on action plan from patient (PA7) | √ | |

- Note: No items in the Risk Communication or Checking for Understanding were used in greater than or equal to 90% of the sessions.

| Skills organized by GCSC categories | Pretest sessions | Posttest sessions |

|---|---|---|

| Building rapport | ||

| Attend to environment (BR1) | √ | √ |

| Introduce self and state title/role (BR4) | √ | |

| Mutual agenda setting & session structuring | ||

| Encourage patient to ask questions (MA4) | √ | |

| Risk communication | ||

| Visual risk presentation used (RC3) | √ | √ |

| Frame risk to reduce bias (RC4) | √ | √ |

| Assess or clarify patient risk perceptions (RC5) | √ | |

| Educating | ||

| Use visual(s) that illustrate key points (ED4) | √ | √ |

| Give written material summarizing educational information (ED5) | √ | |

| Checking for understanding | ||

| Use of teach-back or question/statement getting patient to summarize information given (CU2) | √ | √ |

| Facilitating decision-making | ||

| Provide or use decision aids (FD3) | √ | √ |

| Provider or patient lists pros/cons or give scenarios of what others have done and why (FD5) | √ | |

- Note: No items in the Recognizing and Responding to Emotions and Prior Experiences and Promoting Patient Activation categories were used in less than 30% of the sessions.

3.4 Overall quality ratings and comments

SP session quality ratings on a scale of 1–10 were generally high, with an average of 8.28 (range = 2–10). In comparison, overall quality ratings of the sessions by third-party observers (coders) on a scale of 1–10 had a lower average subjective rating of 7.08 and a smaller range of 3–9.

SPs provided open-ended comments for 42 (66%) of the sessions (including 21 sessions with high SP ratings of 9 or 10 and 21 sessions that were rated lower (mostly 7 to 8)). SPs failed to comment on the remaining sessions. As shown in Table 3, positive comments were far more prevalent than constructive comments even among the lower-rated sessions. All but one of the constructive comments came from SPs who scored the sessions an 8 or less. Nearly half of all lower-scoring sessions had an SP note that the counselor included too much or poorly delivered information. Additionally, SPs from nearly a quarter of the lower-rated sessions wanted more counseling aspects addressed or desired the expression of more empathy from the counselor. The only constructive comment from a higher-scoring session related to the SP wanting the session to be longer and had nothing to do with the genetic counselor, the skills they used, or the session content.

| Themes | Example quotes | Number (%) of sessions where theme was noted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SP rating of 9 or 10 (n = 21) | SP rating of 8 or less (n = 21) | ||

| Positive themes | |||

| Empathy and understanding |

“…let me express my fears and concerns” “was made to feel comfortable, and was receiving good care” “The counselor was very supportive and non-judgmental” “did a good job addressing concerns” “very good listener” |

14 (67%) | 6 (29%) |

| Activated/empowered to address current or future issues (anticipatory guidance) |

“helped me make a plan rather than telling me the plan” “[GC] was extremely helpful in asking questions that helped me clarify my own thoughts.” “…concrete information helped inform my current concerns as well as what might be my future concerns.” “…and providing objective advice, as well as guidance for how we could continue the conversation at home.” “Also, [liked] giving me a warning that the results may cause anxiety” |

12 (57%) | 5 (24%) |

| Valued information provided (at least some of it—particularly parts they viewed as interesting, tailored, or helped initiate action) |

“The genetic counselor was incredibly thorough.” “They also were able to explain why testing is important and how I can use that information moving forward.” “…and took the time to explain my condition and how my family history is contributing…” “listened…and tailored the information accordingly” “[GC] presented a lot of really interesting information, but most of it didn't really seem relevant…” |

8 (38%)a | 7 (33%)b |

| Clear, understandable information and visuals |

“very digestible format” “the counselor had very clear and helpful slides” “I really liked the hand gestures to make sense of what was said.” “I really appreciated the visual of carrier status.” |

3 (14%) | 6 (29%) |

| Admirable GC characteristics |

“smart, but not arrogant” “…positive energy” “…knew what she was talking about…” “they appeared more confident” |

3 (14%) | 5 (24%) |

| Good balance of counseling and education skills | “I really appreciated mix of counseling and education with a greater emphasis on counseling when it came to making a hard decision.” | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| Constructive themes | |||

| Too much information/poor delivery |

“I felt I got a lot of information very quickly which was overwhelming.” “There was a lot of empty and awkward space. The session could have ended earlier.” “I felt rushed at times by the counselor or pressured to follow their format.” “Eliminating some medical jargon might help clarify things…” |

0 (0%) | 10 (48%) |

| Desired more empathy or counseling aspects |

“…it might have been helpful to check in and discuss concerns and perspectives in addition to asking if we had questions.” “I felt like the session did not include empathy.” |

0 (0%) | 5 (24%) |

| Concern about introduction | “The introduction was a bit scattered” | 0 (0%) | 3 (14%) |

| Needed more time | “The only thing wrong was that we could have used more time.” | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

- a Five of the eight who valued the information did so because it helped empower or activate them in specific ways.

- b Four of the seven who provided positive remarks about the information also stated too much information was included or it was poorly delivered.

Positive comments from higher-rated sessions were more often related to the genetic counselors' empathy and understanding. In contrast, lower-rated sessions had more positive comments related to the counselors' professionalism, knowledge, or confidence. SPs who participated in both higher- and lower-rated sessions provided similar numbers of positive comments about how they valued the information provided by the genetic counselor. However, for higher-rated sessions, SPs often tied the value of the information to ways in which it helped activate or empower them. In contrast, comments on the value of information from lower-rated sessions were often followed by remarks about how there was too much information or the information was presented poorly.

4 DISCUSSION

This is the first study to use the GCSC to examine variability in skills used across a series of 64 simulated sessions with practicing genetic counselors from three specialties. Compared to the Genetic Counseling Video project, we had fewer overall sessions but with a more diverse sample of racial and ethnic backgrounds as well as gender identities for both GCs and SPs (Roter et al., 2006). The study demonstrated that genetic counselors from different training programs throughout the United States, with varying years of clinical experience, utilize a broad array of skills across specialty types and indications. This was evidenced by our finding that an average of 64% of the 56 GCSC skills were used per session. Although genetic counselors appear to use a foundational set of skills regardless of specialty, these vary across pretest versus posttest sessions. For example, genetic counselors “elicited the patient agenda” and “established a mutual understanding for the visit” in nearly all pretest sessions, while they “detailed and summarized an action plan” and “included support resources or referrals” in most posttest sessions. These findings suggest that when first meeting a patient, specific items under the skills category of “Mutual Agenda Setting & Session Structuring” may be more useful, whereas, when giving results that will need to be acted upon, other skills belonging to the “Promoting Patient Activation” category may be prioritized.

Genetic counselors in our study almost always “demonstrated respect,” “used active listening skills,” and “maintained an appropriate affect.” These skills are fundamental to the genetic counseling profession that has drawn on Rogerian counseling, which emphasizes the importance of listening, reflecting, and remaining nonjudgmental (Austin et al., 2014). In line with the principle of autonomy, which is often prioritized by the profession, genetic counselors in this study almost always “listed or ensured patients were aware of medically appropriate options or actions” in both pre- and posttest sessions. Additionally, genetic counselors in our study almost always “explored possible outcomes of the options” (at least in pretest sessions). Notably, these latter two skills align with shared decision-making (SDM) (Elwyn et al., 2017). SDM as perceived by the patient has been associated with higher levels of patient satisfaction and affective and cognitive outcomes in nongenetic counseling settings (Shay & Lafata, 2015). Although prior studies have found that genetic counselors score high on SDM (Birch et al., 2019), our results suggest there may still be room for improvement by increasing use of other SDM skills that help patients choose an option that maximizes the benefits most important to them and minimizes potential harm. For example, we found that “listing pros/cons of decisions” or “giving scenarios of what others have done and why” were skills used in fewer than 40% of pretest sessions and only about 30% of posttest sessions. Decision aids were also seldom used, even though they can help patients determine which option best aligns with their values (Stacey et al., 2024).

The SDM skills described above are among other infrequently used skills previously linked to positive patient outcomes or experiences. For example, the use of “teach-back” to get patients to summarize information has been shown to improve the quality of patient education and patient satisfaction in other medical settings such as nursing (Oh et al., 2023). However, “teach back” was rarely used in our study as a way of checking for patient understanding. Additional skills, including the use of visual aids in educating and risk provision, were also infrequently used. This finding may be explained by results of a prior study where genetic counselors reported how video and telephone sessions made the use of visual aids difficult (Burgess et al., 2016; Turchetti et al., 2021). Nevertheless, visuals are widely recognized for their potential to enhance patient understanding in medical settings, including genetic counseling (Houts et al., 2006; Paling, 2003; Pederson et al., 2024). Visual aids can simplify complex information, making it easier for patients to understand. Additionally, when visual aids were developed with input from persons with low literacy, significant improvements have been noted in health literacy outcomes as well as benefits in medication adherence and comprehension (Kua et al., 2021). In the current study, SPs commented on the few visuals used by genetic counselors and indicated that they were appreciated; however, one study using the genetic counseling video project found that patient-centered communication (as measured by the RIAS) was negatively associated with visual aid use and that those with the highest visual aid use also used more genetics terminology. This highlights the importance of using visual aids to reinforce key messages while reducing the amount of medical jargon and attending to the health literacy needs of patients. Other risk communication skills were also uncommonly used despite their potential benefits for individuals with low levels of health numeracy who are more prone to bias and misunderstandings (Reyna et al., 2009). When risk is not communicated well, individuals' health behaviors and health decision-making can be negatively impacted (Reyna et al., 2009). Thus, “assessing understanding of risk” and “presenting risks as both the chance of having the risk or not having the risk” may be useful skills to reduce biases and inform health decisions (Reyna & Brainerd, 2008).

Prior research suggests that communication may impact patient outcomes or patient experiences (Athens et al., 2017; Madlensky et al., 2017). SPs in this study valued the educational components of the sessions, particularly information they felt helped empower them to make decisions or take action (as was often the case in higher-rated sessions). However, in many of the lower-rated sessions, SPs felt there was too much information or the information was perceived as less relevant. These findings may lend some support to the argument that focusing on information-giving at the expense of counseling is an issue of importance in genetic counseling (Schaa & Biesecker, 2024). SPs in our study rated sessions higher when they felt that GCs were demonstrating empathy and understanding. This, together with the lack of negative comments about the use of psychosocial or counseling skills, would suggest psychosocial and counseling skills are valued and should be used to balance out the provision of information.

4.1 Strengths, limitations, and future directions

Although prior studies of genetic counseling sessions unearthed broad trends and counseling patterns (Roter et al., 2006) or focused on specific aspects of sessions (such as risk communication or decision-making), this is the first to evaluate a wide variety of unique skills and compare their use across specialties and pre- and posttest sessions. Valuable insights were gained from SPs who placed themselves in the patient role and provided overall ratings as well as specific comments defining the GC's perceived use of skills. Collaborating with SPs, who are trained to provide constructive feedback, may help to more clearly define quality genetic counseling by allowing for direct comparisons of multiple genetic counselors with reduced variation in session and patient characteristics. SPs have previously been found to be far more likely than real patients to rate providers as “poor” in communication skills, suggesting that SPs are more discerning (Rezaei & Mehrabani, 1969). Although SPs may not be able to fully evaluate a genetic counseling session according to how an actual patient may react, a previous study revealed that SPs had similar ratings as real patients despite using a broader range of scores (Altshuler et al., 2023). Given the presence of SPs, genetic counselors may have responded differently or used different skills than they typically do. Future studies examining perceptions of the use of certain genetic counselor skills from multiple SPs, actual patients, or the public could expand our understanding of the value of strategies used by GCs. Finally, our results are based upon only six unique case simulations, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Skills usage may be influenced by the specifics of each case or SP. However, several skills were used routinely across specialties and cases, revealing general trends. Nonetheless, skills usage for a wider variety of cases is a future area of research and may reveal clear differences. Additional research is needed to confirm the variety of GC skills used across a broader array of cases with actual patients. Statistical analyses were not completed because power to detect associations was limited due to a small sample size. The field needs larger numbers of sessions with a wider variety of patients and indications to assess specialty-specific significant differences in GCSC skills used. Although it is possible that certain skills may be linked to patient-reported outcomes, it may also be contingent on the counselor's adeptness at using the skills. Given that the GCSC fails to capture how well a GC completes a skill, future research may be needed to evaluate the quality of skills used or how often skills are employed. Despite the limitations and need for additional studies, we produced a valuable training resource demonstrating a variety of skills GCs use. This course can help train researchers on the use of the GCSC to capture which skills are used in genetic counseling sessions. The course may also be a useful learning tool for prospective or current genetic counseling students, as it thoroughly details key components of genetic counseling sessions (e.g., mutual agenda setting) and allows students to learn about a genetic counseling skill and understand what the skill might look like in action. Using the simulated sessions, we were also able to identify commonly used skills in genetic counseling sessions as well as skills that may be underutilized, even though they have been effective in other healthcare settings.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Authors HAZ and DLC confirm that they had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All of the authors gave final approval of this version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Academic Investment Education Program from the University of Minnesota grant, “Promoting the Integration of Genetics & Genomics into Clinical Care and Research in Minnesota.” This was a compilation of four master's students projects and conducted to fulfill degree requirements as a part of their training. We thank Jordan Bruer, Helen Atkins, and Brooke Fiedler, who piloted the GCSC training course and gave valuable feedback on its use. Our thanks to the M Simulation staff who coached the SPs, including Joe Miller, and to Aaron Yeshe for technical support with the videos.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Human Studies and Informed Consent: Approval to conduct this human subjects research was obtained by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all standardized patients and genetic counselors to be included in the study.

Animal Studies: No nonhuman animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.