Psychological state at the time of psychiatric genetic counseling impacts patient empowerment: A pre–post analysis

Abstract

Psychiatric genetic counseling (GC) has been associated with patient-reported increases in empowerment (perceived control, emotional regulation, and hope). We sought to evaluate the extent to which patients' psychological state at the time of GC is related to changes in empowerment. Participants with a history of major depressive disorder and/or bipolar disorder that had been refractory to treatment underwent psychiatric GC remotely from 2022 to 2023. GC was performed by four genetic counselors and included discussion of perceived causes of illness, multifactorial inheritance, and protective factors. Empowerment, depression, and anxiety were measured immediately prior to GC via online survey by the GCOS-16, PHQ-9, and GAD-7, respectively. Empowerment was re-assessed 2 weeks later. In total, 66/161 (41.0%) invited individuals completed both the baseline and follow-up surveys. Participants completing both surveys were 54.6% female, 84.8% white, and ranged in age from 22 to 78 years (mean = 54.8 years). Overall, a significant change in mean empowerment was not observed (p = 0.38); however, there were moderating effects by baseline psychological state. A multiple linear regression model incorporating PHQ-9, GAD-7 and baseline GCOS-16 score predicted change in empowerment with a large effect (F = 5.49, R2 = 0.21, p < 0.01). A higher score on the PHQ-9 was associated with decreases in empowerment from pre to post GC. Higher scores on the GAD-7 and lower baseline GCOS-16 scores were associated with increases in empowerment. Further, two-way ANOVA was conducted to assess change in empowerment between subgroups based on the level of anxiety and depression. Those with low depression and high anxiety reported significant increases in empowerment (F = 6.64, p = 0.01). These findings suggest that psychiatric GC may be especially helpful to individuals experiencing anxiety and low baseline empowerment. Alternative approaches may be needed to best meet the needs of those experiencing significant depression.

What is known about this topic

Psychiatric genetic counseling is an effective intervention for individuals with a personal or family history of mental illness and has been associated with statistically significant and clinically meaningful increases in patient-reported empowerment.

What this paper adds to the topic

Our findings suggest that psychological state and empowerment at the time of genetic counseling impact the degree to which individuals experience increases in empowerment. Overall, greater anxiety and lower baseline empowerment were associated with increasing empowerment after GC, whereas greater depression was associated with decreased empowerment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Psychiatric illness is common. One in 5 adults in the United States lives with a mental illness, and 1 in 25 have a diagnosis of a serious mental illness including major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorder (BD) (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018). For a subset of individuals with these diagnoses, currently available treatments do not provide symptom remission despite multiple medication trials and therapeutic interventions. For people with ‘treatment resistant’ depression, depressive symptoms persist without remission after a complete trial of two or more treatments including medication with or without psychotherapy (Brown et al., 2019). Those who live with this diagnosis describe feeling hopeless, trapped, and without control over their lives (Crowe et al., 2023). Many consider experimental therapies, including inpatient treatment trials. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) conducts inpatient treatment trials at the NIH Clinical Center and has prioritized genomics as a key component of their research including starting to offer psychiatric genetic counseling (GC) to current and prior participants (NIMH Strategic Plan, 2021).

Psychiatric conditions are caused by complex and heterogeneous interactions between genetic, environmental, and other factors (Andreassen et al., 2023; Grotzinger et al., 2022). While determining a specific etiology for a particular individual is difficult, psychiatric GC can help patients to understand factors contributing to their illness, address harmful misconceptions, and develop adaptive causal attributions that promote health behaviors and self-acceptance (Austin, 2019). There is evidence supporting the benefits of psychiatric GC among patients with a personal and/or family history of mental illness. Multiple studies have shown that psychiatric GC, with or without genetic testing, is associated with clinically meaningful patient-reported changes to knowledge, understanding, acceptance and internalized stigma, as well as increases in empowerment, which refers to domains of control, emotional regulation, and hope (Borle et al., 2018; Hippman et al., 2016; Inglis et al., 2015; Moldovan et al., 2017). Patients report that understanding the genetic and environmental factors that contribute to mental illness reduced guilt and self-blame and promoted self-efficacy (Putt et al., 2020; Semaka & Austin, 2019). Gerrard et al. (2020) found that lower baseline empowerment and concerns about recurrence risk were associated with greater increases in empowerment. Though this study did not show significant differences based on patient-reported diagnosis, psychological state at the time of GC was not measured. Importantly, there is recent evidence that access to GC may be associated with adherence to recommended treatments (Semaka & Austin, 2019), decreased psychiatric symptoms over time (Morris et al., 2021), and even potentially decreased psychiatric hospitalizations (Morris et al., 2024). However, no studies have previously measured and reported on the effect of psychological state at the time of GC on patient-reported outcomes.

Studying the impact of GC for individuals actively experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression is important to allow for a clearer understanding of who is most likely to benefit and where additional strategies may be needed when resources are limited. This work is particularly vital among those for whom traditional treatments have been ineffective and alternative, evidence-based interventions are urgently needed. To build upon prior work while providing GC to patients who have not historically had access through a traditional clinical model, our study aimed to (1) characterize empowerment among patients with treatment resistant major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder before and after receiving GC and (2) examine the possible moderating role of psychological state at the time of GC on change in empowerment pre-/post-GC.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study procedures

Our team recruited participants as part of a larger genome sequencing study via email outreach to individuals who were evaluated on an NIMH research protocol (NCT04877977 or NCT00024635) between 2005 and 2021. Eligible individuals were over 18 years old, English speaking, and had a history of major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. The majority of participants had a diagnosis that was considered to be ‘treatment resistant’ due to two or more confirmed prior therapeutic trials without symptom remission. We invited interested participants to schedule a virtual appointment with a genetic counselor.

During the appointment, participants provided written informed consent for the survey study and larger genome sequencing study, which involved research-based genome sequencing and return of clinically significant primary and secondary findings. Following consent, we invited participants to complete an online baseline survey in REDCap assessing causal attributions for their history of psychiatric illness, the label they use to describe their illness, current psychological state, and empowerment (refer to section below for measures). Participants completed the baseline survey while on the GC call so that our team could assess safety in response to psychological screening measures. All genetic counselors were trained in suicide risk assessment and an NIMH psychiatrist was available by phone in case urgent intervention was needed.

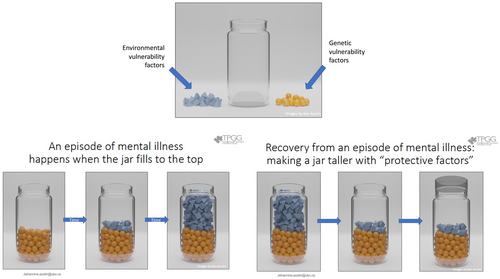

After the baseline survey, GC was provided following the evidence-based process developed by the Adapt Clinic at the University of British Columbia (Austin, 2019), and described here in accordance with the 2017 NSGC Task Force standards for reporting GC interventions (Hooker et al., 2017). GC was provided by one of four certified genetic counselors via phone or secure video call. Session duration ranged from approximately 45 min to 2 h. Session structure and specific content was individualized, but generally included elicitation of perceived factors contributing to mental illness, including significant environmental factors surrounding symptom onset and full family history evaluation with pedigree construction. The jar model was utilized to illustrate multifactorial inheritance and was personalized to include environmental factors and family history information shared by the participant (Austin, 2019, Figure 1). The counselor encouraged participants to share their responses to the jar model in the context of their lived experience. Participants also engaged in collaborative discussion of protective factors and individualized strategies, with an emphasis on anticipatory guidance surrounding the relief of guilt when it is challenging to engage in these behaviors. Recurrence risks were provided if requested by the participant following more generalized discussion.

While these informational components were included to some degree in each session, the overarching encounter was psychotherapeutically oriented, with a focus on developing a therapeutic alliance to facilitate meaning making by the participant (Austin et al., 2014). Goals of the session were individualized but generally included increasing understanding of the complex factors that contribute to the development of mental illness and addressing potential misconceptions, illuminating, and processing internalized feelings including guilt and shame, and helping the participant to identify their strengths and available tools.

Two weeks after the GC session, participants received a follow-up online survey via email containing the same questions from the original survey about causal attribution and empowerment. This time interval was selected to maximize response rate and recall (Bjertnaes, 2012). Genetic counselors were available for additional discussion as needed. This study was approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) as part of protocol 17-I-0122 (NCT03206099).

2.2 Measures

The Genetic Counseling Outcome Scale (GCOS) is a 24-item questionnaire designed to capture the construct of empowerment, made up of five domains: decisional control, cognitive control, behavioral control, emotional regulation, and hope (McAllister et al., 2011). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Scores range from 24 to 168 with higher scores signifying higher levels of empowerment. The scale has a reported internal consistency of α = 0.87 and test–retest reliability of α = 0.86 (McAllister et al., 2011). The GCOS has been used in multiple prior studies of psychiatric GC services (Borle et al., 2018; Inglis et al., 2015).

Depressive symptoms were assessed via the Patient Health Questionairre-9 (PHQ-9) and symptoms of anxiety were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Kroenke et al., 2001, Spitzer et al., 2006). The PHQ-9 is a self-administered screening measure of depression severity that is part of the longer Patient Health Questionnaire. Initial validation studies involving 6000 respondents indicated that scores of 10 or above had both a sensitivity and specificity of 88% for a diagnosis of major depression with higher scores indicating more severe symptomology (Kroenke et al., 2001). The GAD-7 is a screening tool for assessing symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. Validation studies showed sufficient reliability and validity, as well as distinction from domains measured by the PHQ-9 (Spitzer et al., 2006). Both scales have been widely used in research and clinical practice as effective screening tools and were included in our study to measure psychological state at the time of GC.

2.3 Analysis

Data were formatted and analyzed in SPSS v28.0.1.1 (IBM Corp. Released 2021). The GCOS-24 was transformed into the GCOS-16, a shortened version that has shown evidence for improved performance in the psychiatric GC setting with Cronbach's alpha of 0.82 as compared to 0.39 for the GCOS-24 (Borle et al., 2023). Transformation involves exclusion of 8 items and collapsing the 7-point Likert scale into three response categories. Scores on the GCOS-16 scale range from 16 to 48. Change in empowerment was calculated for each participant by subtracting the GCOS-16 pre-GC score from the GCOS-16 post-GC score. Magnitude of change in mean empowerment for the group was calculated via a paired sample t-test. To detect a change in empowerment comparable to that reported in the literature (16 points on the GCOS-24) at 80% power, our target sample size was 80 pre–post responses (Gerrard et al., 2020). We conducted chi-squared and t-tests for comparison of demographic variables (categorical and continuous, respectively) between participants who completed both surveys and those who completed only the baseline or no survey.

To assess the impact of psychological state on change in empowerment, a multiple linear regression was run with change in GCOS-16 from pre to post as the dependent variable and depression score (PHQ-9), anxiety score (GAD-7) and baseline GCOS-16 score as the independent variables. Demographic variables were not included, as these have not been associated with differential change in empowerment in a larger cohort (Gerrard et al., 2020).Additionally, the sample was split into low and high anxiety and depression groups using established clinical cutoffs for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 (scores < 10 corresponding to absent or mild symptoms were coded as low; scores ≥ 10 corresponding with moderate to severe symptoms were coded as high). Two-way ANOVA was performed relating dichotomized PHQ-9, GAD-7, and an interaction term PHQ-9*GAD-7 as fixed effects with change in empowerment. To determine the proportion of variance explained by the interaction, we performed a multiple linear model including the interaction term for PHQ-9*GAD-7 in addition to the main effects of PHQ-9, GAD-7 and baseline GCOS-16.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participant characteristics

Demographic data were collected by patient self-report at the time of initial NIMH research involvement (2005–2021) and are summarized in Table 1. In total, 161 participants consented to the study and underwent genetic counseling. Of those, 111 completed at least one survey and 66 completed both the baseline and follow-up surveys. Among the 66 participants completing both surveys, 54.5% identified as female, 84.8% identified as White, and 4.5% as Hispanic or Latino. Ages for the cohort ranged from 22 to 78 years (mean = 54.8) and years living with a mental illness ranged from 6 to 71 (mean = 35.0). There was a statistically significant difference in the number of participants identifying as Asian in the group completing both surveys (n = 4) as compared with the remainder of the cohort (n = 0; p = 0.02). There were no other significant demographic differences between the two groups (Table 1).

| Demographic data | Pre- & Post-survey Completed (N = 66) | Pre- & Post-survey not Completed (N = 95) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 30 | 45.5% | 49 | 51.6% | 0.44 |

| Female | 36 | 54.5% | 44 | 46.3% | 0.30 |

| Non-binary | 0 | - | 2 | 2.1% | 0.23 |

| Race | |||||

| American Indian, Alaska native | 0 | - | 2 | 2.1% | 0.23 |

| Asian | 4 | 6.1% | 0 | - | 0.02* |

| Black/African American | 6 | 9.1% | 8 | 8.4% | 0.88 |

| Multiple Races | 0 | - | 3 | 3.2% | 0.14 |

| White | 56 | 84.8% | 75 | 78.9% | 0.34 |

| Unknown | 0 | - | 7 | 7.4% | N/A |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 | 4.5% | 3 | 3.2% | 0.65 |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 63 | 95.5% | 83 | 87.4% | 0.08 |

| Unknown | 0 | - | 9 | 9.5% | N/A |

| Mean (range) | Mean (range) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.8 (22–78) | 52.7 (25–76) | 0.29 |

| Years living with mental illness | 35.0 (6–71) | 32.4 (8–75) | 0.40 |

| Psychological state at baseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure (Scale), possible range | Pre- & post-survey (N = 66) | Only baseline (N = 45) | p |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Depression (PHQ-9), 0–27 | 12.0 (6.4) | 12.6 (6.9) | 0.70 |

| Anxiety (GAD-7), 0–21 | 8.5 (5.4) | 9.9 (5.7) | 0.22 |

| Pre-empowerment (GCOS-16) | 27.9 (5.4) | 27.6 (6.2) | 0.78 |

| Post-empowerment (GCOS-16) | 27.8 (5.7) | N/A | N/A |

- Note: There was a statistically significant difference in the number of participants identifying as Asian in the group completing both surveys (n = 4) when compared with the remainder of the cohort (n = 0; p = 0.02). There were no other significant demographic differences between the two groups.

- * Indicates statistical significance (p = <0.05).

Individuals in the study sample completing both surveys (n = 66) reported significant levels of depression and anxiety based on clinical thresholds for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, with 89.4% (59/66) reporting at least mild symptoms of depression and 69.7% (46/66) reporting at least mild anxiety. The mean depression score was 12.0 (SD = 6.4), consistent with moderate depressive symptoms, and the mean anxiety score was 8.5 (SD = 5.4), in the range for mild anxiety. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics or baseline psychological state between the whole cohort (n = 161) and those completing both surveys (n = 66).

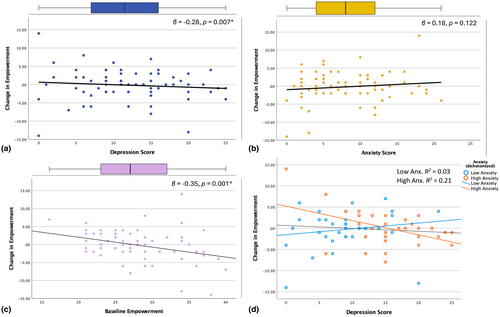

3.2 Impact of GC

Empowerment as measured by the GCOS-16 for those completing both surveys ranged from 16 to 48 with a mean of 27.9 before GC and 27.8 after GC (mean change = 0.17, SD = 4.43). Overall, a significant change in mean empowerment was not observed (t = 0.31, p = 0.38), however, our data indicated moderating effects by baseline psychological state and baseline empowerment with a moderate effect size (R = 0.46). A multiple linear regression model of depression, anxiety and baseline empowerment predicted change in empowerment with a large effect size (F = 5.49, R2 = 0.21, p < 0.01, Table 2a). Greater baseline depression was significantly associated with decreasing empowerment (β = −0.28, p = 0.007), while greater baseline anxiety was associated, though not statistically significantly, with increasing empowerment after GC (β = 0.18, p = 0.122, Figure 2). Lower baseline GCOS-16 scores were associated with greater increases in empowerment (β = −0.35, p = 0.001).

| A. | β | Std. err. | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression score (PHQ-9) | −0.28 | 0.10 | −2.77 | 0.007* |

| Anxiety score (GAD-7) | 0.18 | 0.12 | 1.57 | 0.122 |

| Baseline empowerment (GCOS-16) | −0.35 | 0.10 | −3.45 | 0.001* |

| B. | β | Std. err. | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression score (PHQ-9) | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.952 |

| Anxiety score (GAD-7) | 0.53 | 0.19 | 2.81 | 0.007* |

| Baseline empowerment (GCOS-16) | −0.29 | 0.10 | −2.81 | 0.007* |

| Anxiety/depression interaction (PHQ-9*GAD-7) | −0.03 | 0.01 | −2.29 | 0.025* |

| C. | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p-Value | η 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High/low depression group | 48.73 | 1 | 48.73 | 2.64 | 0.11 | 0.041 |

| High/low anxiety group | 48.51 | 1 | 48.51 | 2.63 | 0.11 | 0.041 |

| Anxiety*depression group interaction | 122.75 | 1 | 122.75 | 6.64 | 0.012* | 0.097 |

- Note: (A) Multiple linear regression model with PHQ-9, GAD-7 and baseline GCOS-16. (B) Multiple linear regression model adding the PHQ-9*GAD-7 interaction term. (C) Two-way ANOVA with dichotomized anxiety and depression. η2 is a measure of effect size (0.01 ≤ η2 < 0.06 = small effect, 0.06 ≤ η2 < 0.14 = medium effect).

- * Indicates statistical significance (p =< 0.05).

Two-way ANOVA with change in empowerment and anxiety and depression (high/low based on clinical cutoffs for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7) indicated a significant interaction between anxiety and depression of medium effect size (F(1,65) = 6.64, p = 0.012, η2 = 0.97, Table 2c). There were no mean differences that reached statistical significance, though those with low baseline depression and high baseline anxiety reported the highest mean increase in empowerment (Table S1). Multiple linear regression models with and without the interaction term show that the PHQ-9*GAD-7 interaction accounted for 5.3% of the variance in change in empowerment (adjusted R2 with interaction = 0.225, adjusted R2 without interaction = 0.172, Table 2b). Figure 2d illustrates the interaction between PHQ-9 and dichotomized (high vs. low) GAD-7.

4 DISCUSSION

Here, we report a study on psychiatric GC for individuals with ‘treatment resistant’ major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder, with a focus on the impact of psychological state at the time of GC on empowerment. Our findings suggest that psychological state impacts the effect of GC on empowerment. Notably, empowerment did show a modest increase 2 weeks after GC in individuals with higher levels of baseline anxiety, particularly in those who had low levels of depression. Our findings suggest that empowerment may be more readily responsive to counseling interventions that promote understanding of etiology and discussion of protective factors in the setting of anxiety than in the setting of depression and may be a particularly salient outcome for this group. Per the GAD-7 scale, individuals in the high anxiety group endorsed varying levels of worry, nervousness, and fear – which could be caused, at least in part, by uncertain expectations of the GC session or misconceptions about the factors contributing to mental illness. A prior study found that positive change in empowerment was greatest among clients who reported that concerns about recurrence risk were their primary motivation for seeking GC (Gerrard et al., 2020). These concerns may be associated with significant anxiety and can also be directly addressed during the counseling session, which is consistent with our findings of a positive change in empowerment among individuals with anxiety as their presenting symptom.

The lack of change in empowerment among individuals experiencing high levels of depression likely reflects the inherent nature of this condition. Major depressive disorder is defined by prolonged symptoms including feelings of hopelessness, excessive guilt, fatigue, changes to appetite, and decreased concentration (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Hope and control are key components of empowerment as measured by the GCOS-16 and may be more difficult to achieve for patients while experiencing a depressive episode. Consistent with this, the mean baseline GCOS-16 score across the whole cohort (27.1, scale ranges from 16 to 48) was lower than the mean of 32.1 reported for a study population with and without symptoms of mental illness at the time of GC (Borle et al., 2023). Participants in our study had tried multiple treatments, including experimental trials, without relief, and consistent with the literature on ‘treatment resistant’ depression may have felt hopeless and at a loss for control over their lives (Crowe et al., 2023). While individuals experiencing depression may benefit from psychiatric genetic counseling, these effects did not translate to significantly increased empowerment as a primary outcome in our study. One way of interpreting the clinical significance of these findings would be to advocate for the development and evaluation of additional counseling interventions and outcome measures to optimize benefit for patients with significant depressive symptoms.

Our study population was also unique in that individuals were proactively contacted with the offer of GC, rather than seeking out this service for themselves. Due to their prior participation and interest in research, many participants in this group already had a deep understanding of the familial and environmental factors that may have played a role in their mental illness. As a result, there may have been a lower burden of misconceptions among this group than in previous studies, and therefore less short-term impact of psychiatric GC. This study population also differs from prior research, which has included a significant number of at-risk relatives in addition to those with a personal history of mental illness.

Other studies have demonstrated that individuals with lower empowerment at baseline as measured by the GCOS-24 experienced greater increases in empowerment, though these analyses were not stratified by psychological state (Gerrard et al., 2020). Our data replicated this pattern, supporting the suggestion from Gerrard et al., 2020 to consider the use of baseline empowerment to optimize the benefits of psychiatric GC. As resources are limited, determining the optimal time, setting and measurable outcomes of GC is essential in expanding access effectively.

4.1 Limitations

Limitations of our study include the size and racial and ethnic homogeneity of the sample completing both surveys. Due to the recruitment method our population was also biased towards individuals who historically had access to research participation. Additionally, all GC sessions were conducted via telemedicine (video or phone call) which may have influenced the results. Gerrard et al., 2020 found that in-person service delivery was associated with greater change in empowerment than telehealth, though this difference was not statistically significant. We also did not include measures of other symptomology, such as psychosis or mania, which may also impact change in empowerment (Hirschfeld, 2002). We also chose not to include diagnosis as a variable due to many participants having multiple diagnoses and diagnostic labels that have changed over time.

4.2 Future directions

The observed lack of change in overall empowerment does not necessarily indicate that psychiatric GC was not beneficial to this group of participants. Other measures may be needed to appreciate the impact of GC amidst active depressive symptoms. To this end, future research should examine the impact of GC on outcomes such as internalized stigma and intention to engage in protective behaviors. Additionally, as our population was enriched for those with major depressive disorder, future studies including more individuals with anxiety disorders would help to clarify the impact of psychiatric GC on empowerment among this group. Our study provides evidence that psychological state at the time of GC affects the degree to which empowerment is influenced by psychiatric GC. This intervention may be most impactful in increasing empowerment among individuals with low baseline empowerment and current symptoms of anxiety.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Authors R.G.M. and C.J. confirm that they had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All of the authors gave final approval of this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the NIAID Centralized Sequencing Program and the Experimental Therapeutics and Pathophysiology Branch at NIMH. Thank you to Pamela Burrows for statistical support. We would also like to thank Holly Peay, Megan Cho, and Lori Erby for their guidance in developing this project, and Dr. Steve Holland and Dr. Maryland Pao for their ongoing support of our work. This research was supported with funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Division of Intramural Research and from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Zarate is listed as a co-inventor on a patent for the use of ketamine in major depression and suicidal ideation; as a co-inventor on a patent for the use of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine, (S)-dehydronorketamine, and other stereoisomeric dehydroxylated and hydroxylated metabolites of (R,S)-ketamine metabolites in the treatment of depression and neuropathic pain; and as a co-inventor on a patent application for the use of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine and (2S,6S)-hydroxynorketamine in the treatment of depression, anxiety, anhedonia, suicidal ideation, and post-traumatic stress disorder. He has assigned his patent rights to the U.S. government but will share a percentage of any royalties that may be received by the government. Authors RGM, CJ, MS, KLL, JY, SB, MY, MW, JCA and MS have no conflicts of interest to declare. The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or the Department of Defense.

ETHICS STATEMENTS

Human Studies and Informed Consent: This study was approved by and conducted according to the ethical standards of the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board as part of protocol 17-I-0122 (NCT03206099). All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines were followed. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Animal Studies: No non-human animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The anonymized data set generated during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.