Mothers' reflections on the diagnosis and birth of their child with Down syndrome: Variability based on the timing of the diagnosis

Abstract

Previous research has examined parents' reflections on their child's Down syndrome diagnosis based on whether the diagnosis was provided prenatally or after birth, revealing few significant differences; by comparison, few studies have examined parents' reflections on the birth of the child in relation to the timing of the diagnosis. This study was conducted to examine whether mothers differentially reported on and rated the diagnosis, birth, and most recent birthday of their child with DS based on when the diagnosis was provided. Forty-four American mothers of children with DS discussed the birth of their child, when they learned of their child's DS diagnosis, and their child's most recent birthday with a researcher. Participants also completed online questionnaires on which they rated the events and indicated how they felt about the events at the time of their occurrence and at the time of the study. The results revealed that participants who received a prenatal diagnosis of DS for their child reflected differently—and seemingly more positively—on their child's birth relative to participants who received a postnatal diagnosis. These differences were evident when considering participant ratings, emotion language used when discussing the events, and feeling states characterizing how participants felt about the events at the time of their occurrence and at the time of the study. Given these group differences, medical professionals should carefully consider the conditions under which they provide mothers with diagnostic information and support services after a child is born.

What is known about this topic

Parents of children with Down syndrome (DS) similarly reflect on learning of their child's diagnosis regardless of whether the diagnosis was provided prenatally or after birth.

What this paper adds to the topic

This research represents a significant extension of the work that has been conducted to date, as we (1) included birth stories in addition to diagnosis events, (2) featured discussion of and ratings on a control event on which the mothers were not expected to differ, and (3) included both quantitative and qualitative measures. Findings indicating that mothers differentially process the birth of their child with DS based on when the diagnosis was provided have important practical implications.

1 INTRODUCTION

Evaluating parents' reactions to the diagnosis and birth of their child with DS is important, as DS is the most common chromosomal abnormality across the globe, affecting approximately one in every 792 infants (de Graaf et al., 2015). Although every individual with DS is unique, DS is characterized by distinct physical features (e.g., almond-shaped eyes, a single crease across the middle of the hands, an enlarged tongue), health challenges (e.g., cardiac problems, sleep apnea; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023), and cognitive delays (for reviews, see Grieco et al., 2015; Lukowski et al., 2019). Although many individuals with DS now live into their 60s or 70s (Zigman, 2013), adults with DS may require ongoing care from aging parents and siblings (Hodapp et al., 2016). For these reasons, welcoming a child with DS into the family necessitates a shift in perspective from what parents may have expected and requires lifelong adjustments in supporting and potentially managing care for their loved one.

Significant advances in genetic screening and testing procedures allow for the identification of DS and other trisomies with up to 99% accuracy through prenatal cell-free DNA screening around 10 weeks gestation (Gray & Wilkins-Haug, 2018). Other screening options also exist, including maternal blood draws and ultrasounds in the first trimester and the quad screening test in the second trimester (e.g., Caughey et al., 2002). Diagnostic assessments are available for mothers who receive an indicator of risk on a screening test. In chorionic villus sampling, cells from the placenta are extracted from 10 to 13 weeks gestation. In amniocentesis, the amniotic fluid is extracted and analyzed for circulating fetal DNA between 15 and 20 weeks gestation (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2024). These procedures not only provide medical diagnoses with up to 100% accuracy but also include a risk of miscarriage (although meta-analyses indicate that the risk of procedure-related miscarriage before 24 weeks is lower than women may believe; Akolekar et al., 2015; Salomon et al., 2019). Despite the availability of prenatal screening and diagnostic tests, approximately 85% of children born with DS are diagnosed after birth (Crombag et al., 2020; Skotko, 2005).

Although the majority of parents who have a child with DS learn that their child has DS postnatally, research is needed to better understand how parents process and reflect on the birth and diagnosis of their child with DS depending on the timing of the diagnosis. Previous questionnaire-based work indicates that although parents report unique challenges regarding the conditions under which the diagnosis is provided depending on whether they learn of their child's diagnosis prenatally (Skotko et al., 2009) or after birth (Skotko et al., 2009), parents report negative reactions to learning of their child's diagnosis regardless of timing of the news, citing fear, anxiety, nervousness, and uncertainty about the future (Clark et al., 2020; Grane et al., 2023; Nelson Goff et al., 2013; Skotko, 2005; Skotko & Canal Bedia, 2005; Smith et al., 2018; Staats et al., 2015). Commonalities have also been identified regarding the best conditions under which to give the diagnosis: Parents prefer to hear the news from a knowledgeable individual in a private space or on a scheduled phone call in the presence of their partner; they prefer that medical professionals use sensitive language and provide a balanced perspective on the diagnosis instead of focusing on the negative; and they prefer to learn of the possibility of a diagnosis of DS as soon as possible, even if the diagnosis is unconfirmed (for relevant work, see Cunningham & Sloper, 1977; Gayton & Walker, 1974; Pueschel, 1985; Schimmel et al., 2020; Skotko et al., 2009). Recommendations have been provided in previous research about how to best deliver the news of a DS diagnosis (Sheets et al., 2011; Skotko et al., 2009); yet approximately half of parents surveyed reported dissatisfaction with the manner in which their child's DS diagnosis was provided (Van Riper & Choi, 2011).

Understanding how parents process and reflect on the birth and diagnosis of their child with DS diagnosis based on when the news is provided may have important implications for their own well-being when their children are young and over the longer term. Parents' memory for their child's DS diagnosis has flashbulb memory-like qualities, such that these memories are particularly vivid and can be recalled in detail decades later (May et al., 2020). Comparatively, little research has been conducted to evaluate how parents reflect on the birth of their children with DS (although see Gabel & Kotel, 2018; Kammes et al., 2022; Lalvani & Taylor, 2008), and none of the work conducted to date to the best of our knowledge has examined parental reflections on the birth of their child in relation to when the diagnosis was received. Although parents of children with DS generally report better functioning than families with children with other disabilities (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Eisenhower et al., 2005; Fidler et al., 2000; Hodapp et al., 2001), it is likely that mothers differ in how they process and reflect on the birth of their child based on whether they receive a prenatal or postnatal diagnosis of DS. That is, the temporal separation between the diagnosis and birth of children who are diagnosed prenatally may allow parents to reflect more positively on the birth of their children relative to parents who learn of their child's DS diagnosis after birth. As such, variability in parental reflections on the birth of their child with DS may be related to parent well-being over and above parental reflections on the diagnosis of their child.

This study was conducted to examine whether mothers differentially reported on and rated the diagnosis, birth, and most recent birthday of their child with DS depending on whether they learned of the child's diagnosis during gestation or after birth. The diagnosis event was included to replicate previous research, the birth event was included as a novel extension, and the most recent birthday was included as a control event. Based on previous research directly comparing the reactions of parents who received prenatal or postnatal diagnoses (Nelson Goff et al., 2013; Staats et al., 2015), we predicted that group differences by the timing of the diagnosis would not be found on the diagnosis event but would be evident on the birth event. In particular, we anticipated that participants who received a prenatal diagnosis would reflect more positively on their child's birth relative to participants who received a postnatal diagnosis. We expected that these differences would be apparent on participant ratings, language used when discussing the events (e.g., more positive and less negative language used by participants who received a prenatal relative to a postnatal diagnosis), and self-reported feeling states (i.e., how participants felt about the event at the time of its occurrence, as reported retrospectively, and at the time of the study). We predicted that group differences would not be found when considering reflections on the child's most recent birthday given the temporal distancing from the grouping event (i.e., when the diagnosis was provided). In addition, we predicted that group differences would not be found on measures of participant well-being (i.e., satisfaction with life) at the time of the study, but that variability in participant reflections on the birth of their child in particular would be related to satisfaction with life at the time of the study. If realized, these findings would have important implications for medical professionals who help mothers manage their emotions and cognitions surrounding the birth of their child with DS by taking into consideration when they learned of their child's diagnosis.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

Forty-six mothers of children with DS were recruited to participate; 44 mothers completed the study (the data from two participants were excluded due to poor audio quality). Participants were recruited from the LuMind IDSC Research and Medical Care Facebook group, as this page has a large membership (approximately 1400 members in June 2024), features posts about support and services for families with children with DS, and includes advertisements for research opportunities. Recruitment advertisements were posted by a site administrator in April and October 2019; participants were also asked to post our recruitment information on their personal Facebook pages and to spread the word through their social networks (i.e., snowball sampling). Eligible participants (1) had only one child with Down syndrome who was between the ages of 1 and 17 years old at the time of the study, (2) gave birth to that child, (3) lived in the United States, and (4) were comfortable engaging with the study team in English. At the end of the study, participants received a $20 electronic gift card in thanks for their involvement.

2.2 Instrumentation

Participants completed an online battery of questionnaires at the first session as well as an event-specific online questionnaire at the second session.

2.2.1 Demographic questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire presented at the first session inquired about information relevant to the participant and her child with DS. Questions inquired about race and ethnicity information, pregnancy- (e.g., whether the participant obtained prenatal care, during which trimester prenatal care began) and birth-related information (e.g., whether the child was three or more weeks premature, whether the child spent any time in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, whether the child participated in early interventions and at what age intervention began), along with other general demographic variables (e.g., participant marital status, education, family income, number of biological children, whether participants attended religious services in the past year, etc.).

Participants also reported on their evaluation of child functioning at the time of the study when considering physical abilities, intellectual and cognitive functioning, independence, and activities of daily living. Each of these items was rated on a sliding scale from 1 to 7, with higher values indicating better functioning.

2.2.2 Subjective well-being

Toward the end of the first session questionnaires, participants completed the 5-item Satisfaction with Life scale (Diener et al., 1985) as a measure of subjective well-being. Each of the items (e.g., “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing”) was rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Diener et al. (1985) reports that this measure is psychometrically sound and aligns well with other indicators of subjective well-being (in this study, α = 0.88).

2.2.3 Event ratings1

Participants rated the frequency with which they thought about each event (from 1 = never or rarely to 7 = almost every day), the frequency with which they talked about each event (from 1 = never or rarely to 7 = almost every day), the significance of each event when it occurred and at the time of the study (1 = not significant to 7 = very significant), the uniqueness of the event when it occurred (1 = happens often to 7 = completely unique), whether they had pictures of each event (0 = no, 1 = yes), and how confident they were that the reported event was based on their own memory and was not based on pictures or conversations (1 = not very confident to 7 = very confident). Participants also reported on the valence of each event when it occurred and at the time of the study (−3 = very negative to 3 = very positive), in addition to recording three different emotion terms reflecting their feelings about each event when it occurred and at the time of the study.

2.3 Procedure

This research was approved as self-determined exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Irvine. Participant testing occurred from April to November 2019.

2.3.1 Session 1

Participants clicked the link on the recruitment advertisement to open the first study session questionnaire. After reviewing the online study information sheet (waiver of written informed consent), participants completed the first session questionnaire. Toward the end of the first session questionnaire, the participants were redirected to an online scheduling site on which they scheduled a 1-h video chat interview on Zoom (www.zoom.us) with a research assistant. On average, the interviews were scheduled approximately 10 days after completing the first study session (range: 1–51 days).

2.3.2 Session 2

Participants were emailed a link to their individual video chat interview after they completed the first study session. Interviews were conducted with video and audio so that the researcher assistant (RA) and the participant could interact as naturalistically as possible, but only the audio was recorded for later transcription and analysis.

Participants were asked to discuss three events with the research assistant, including when they learned of their child's DS diagnosis, their child's birth story, and their child's most recent birthday. The events were discussed in chronological order, such that participants who received a prenatal diagnosis of DS for their child discussed the diagnosis event followed by the birth story and the child's most recent birthday; participants who received a postnatal diagnosis of DS for their child reported on their child's birth story followed by the diagnosis event and the child's most recent birthday. The prompt for each event included the reminder that participants take as much time as needed to discuss the event and the request that they share as much detail as they were comfortable providing, including any emotions they had experienced. As participants discussed the events, the RA provided brief general affirmations but did not engage in conversation with the participants about their experiences. After the three events were discussed, the participants were emailed a link to the second online questionnaire, so they could rate each of them in succession on the dimensions described previously. Once the ratings were complete, the video chat interview was terminated.

2.4 Data reduction

2.4.1 Transcription

The audio recordings were separated out into three discrete events (i.e., the diagnosis event, the birth event, and the most recent event) to facilitate transcription. The audio files were submitted to a human online transcription service for processing; each transcript was then independently reviewed for accuracy by two research assistants. Speech that was difficult to understand was recorded in brackets; unintelligible speech was recorded in the transcript as XXX.

2.4.2 Internal states coding

Data coding was conducted using a positivist (Wainstein et al., 2022) inductive content analysis framework (Vears & Gillam, 2022) that included quantitative elements. Following a positivist epistemological approach, our goal was to create generalizable knowledge through the precise, scientific assessment of maternal discourse (Wainstein et al., 2022, tab. 1). We approached this goal methodologically by (1) familiarizing ourselves with the narrative data, (2) identifying broad coding categories (i.e., cognition and emotion terms), (3) developing coding subcategories (e.g., positive emotion terms and negative emotion terms), (4) refining categories based on the distribution of the data, and (5) reducing and interpreting the data quantitatively (Vears & Gillam, 2022, pp. 117–125), as described below.

One undergraduate RA coded the emotion terms used in each narrative and a second RA coded the cognition terms; the second author served as the reliability coder for both. Emotion terms were coded for whether they were positive, negative, or neutral; general or specific; whether the term referenced the self, other, or a group; and whether the term was modified high, low, or not at all (e.g., the phrase, “our baby was valuable to us” was coded as positive, general, group, no modifiers). For analysis, terms were collapsed across categories to yield separate dependent measures for positive, negative, and neutral emotion terms. Reliability was computed across events on approximately 32% of the sample (n = 14); average κ = 0.96 (range from 0.82 to 1.00).

Cognition terms were coded to indicate whether they were said (e.g., “I understand”) or negated (“I don't remember”); whether the term referenced the self, other, or a group; and whether the term was modified high, low, or not at all (e.g., the phrase, “I don't want…” was coded as negated, self, no modifiers). Because of the relatively low incidence of negated cognition terms, terms were collapsed across categories to yield one measure of cognition term use. In addition, the filler phrase “you know” was excluded from analysis (e.g., “you know, we took a really long time to tell family”). Reliability was computed across events on approximately 32% of the sample (n = 14); average κ = 0.95 (range from 0.82 to 1.00).

2.4.3 Analysis plan

(1) Between-subjects analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and chi-square analyses were conducted to identify group differences in demographics and child functioning. (2) Mixed ANOVAs were conducted by group (between-subjects: prenatal or postnatal) and event (within-subjects: diagnosis and birth) on maternal ratings pertaining to frequency of conversation, frequency of thought, uniqueness, vividness, and confidence that the memory was their own and was not impacted by pictures or conversations with others. Mixed ANOVAs including factors of group, event, and time (within-subjects: time of the event or time of study) were conducted on event valence and significance. Chi-square analyses were conducted to determine whether the percent of participants who had pictures of the diagnosis and birth events differed by group. (3) Mixed ANOVAs were conducted by group and event on the total number of words used in the narratives. Mixed ANOVAs including factors of group, event, and valence (within-subjects; positive, negative, and neutral) were conducted on emotion term use; a mixed ANOVA including factors of group and event was conducted on cognition term use. (4) Parallel analyses were conducted to examine group differences on the most recent birthday event excluding the factor of event (as the most recent birthday was the only event considered).

To facilitate reading and comprehension of the Results section, all statistical effects are presented in the Tables S1–S3. Significant effects are presented when p ≤ 0.05 but are only described within the highest order interaction in which they are featured. The results of Fisher's exact tests (FET) are presented in lieu of chi-square analyses when at least 25% of the tested cells had expected counts of less than five (Kim, 2017).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographic information (Table S1)

Group differences were not found on any of the collected maternal variables; one group difference emerged when considering child demographics. Specifically, a greater percentage of children who were diagnosed with DS after birth had a sibling relative to children who were diagnosed prenatally. A significant group difference was also found on current activities of daily living, such that children who received a prenatal diagnosis of DS had higher scores (i.e., better daily functioning) relative to children who received a postnatal diagnosis. Despite these group differences, we adopt the position of Miller and Chapman (2001) who caution against controlling for a priori group differences in ANOVAs.

3.2 Diagnosis and birth events (Table S2)

3.2.1 Event ratings

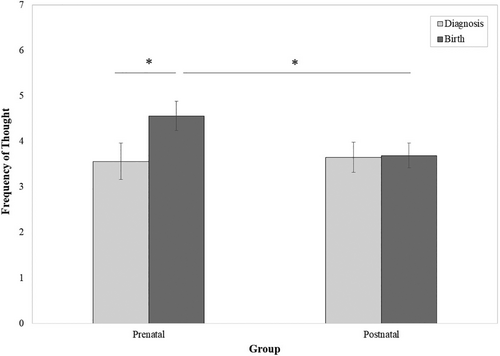

A main effect of event was qualified by a group × event interaction for frequency of thought. As shown in Figure 1, follow-up analyses conducted by group indicated that participants who received a prenatal diagnosis thought more about their child's birth relative to their diagnosis; differences by event were not found for participants who received a postnatal diagnosis. Follow-up analyses conducted by event revealed that participants who received a prenatal diagnosis thought more about their child's birth relative to participants who received a postnatal diagnosis; group differences were not found for the diagnosis event.

Similarly, a main effect of event was qualified by a group × event interaction for the frequency with which participants talked about the events. As shown in Figure 2, follow-up analyses conducted by group indicated that participants who received a prenatal diagnosis talked more about their child's birth relative to their diagnosis; differences by event were not found for participants who received a postnatal diagnosis. Follow-up analyses conducted by event revealed no significant differences by group for either the diagnosis or birth events.

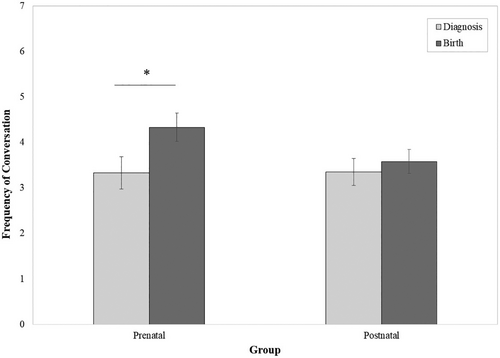

When considering the significance of the events, a main effect of time was qualified by a group × event × time interaction. Follow-up simple effects analyses were conducted by event to better understand how participants differentially processed the diagnosis and birth of their child based on when they learned their child had DS. As shown in Figure 3, a main effect of time was found for the diagnosis event. For the birth event, a main effect of time was qualified by a group × time interaction. Follow-up analyses revealed that the postnatal group rated the birth event as more significant at the time of its occurrence relative to at the time of the study; significant effects were not found for the prenatal group. Follow-up analyses conducted by time indicated that, at the time of the study, the prenatal group rated the birth event as more significant than the postnatal group; group differences were not found at the time of the events.

Significant effects were also found on event valence, though not involving group. That is, main effects of event and time were qualified by an event × time interaction. As shown in Figure S1, follow-up analyses conducted by event indicated that participants rated the diagnosis and birth events as more positive at the time of the study relative to at the time of their occurrence. Follow-up analyses conducted by time indicated that participants rated the birth event more positively than the diagnosis event both at the time of their occurrence and at the time of the study.

Finally, a main effect of group was found for confidence that one's memories were one's own and were not influenced by pictures or conversations with others, such that the prenatal group reported greater confidence in their memories (6.94 ± 0.12) relative to the postnatal group (6.62 ± 0.10). Significant effects were not found on dependent measures pertaining to the vividness or uniqueness of the events or when considering access to pictures of the reported events.

3.2.2 Internal states language

Significant effects of group, event, or their interaction were not found on total words used in the narratives. When considering cognition terms, only a main effect of event was found, such that participants used more cognition terms when discussing birth (51.78 ± 7.54) relative to diagnosis events (41.41 ± 7.19).

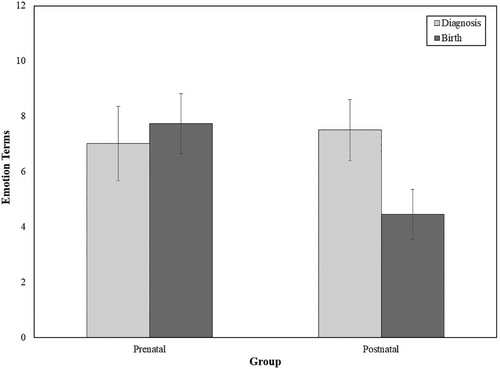

When considering emotion term use, a group × event interaction was found. As shown in Figure 4, follow-up analyses conducted by group indicated that participants who received a postnatal diagnosis used more emotion terms when discussing the diagnosis event relative to the birth event; differences by event were not found for participants who received a prenatal diagnosis. Follow-up analyses conducted by event revealed that participants who received a prenatal diagnosis used more emotion terms when discussing their child's birth relative to participants who received a postnatal diagnosis; group differences were not found for the diagnosis event.

A main effect of valence was also found and was qualified by an event × valence interaction. As shown in Figure S2, follow-up analyses conducted by valence indicated that participants used more negative emotion terms when discussing the diagnosis relative to the birth event; differences by event were not found for positive and neutral emotions. Follow-up analyses conducted by event indicated that participants used more positive than neutral terms when describing the birth event; for the diagnosis event, participants used more negative than neutral terms; differences among the other emotion categories were not found.

3.2.3 Feeling states

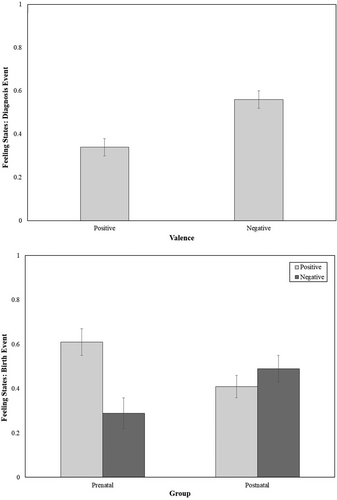

A significant event × valence interaction was qualified by an event × valence × group interaction. Follow-up simple effects analyses were conducted by event to better understand how participants differentially processed the diagnosis and birth of their child based on when they learned their child had DS. As shown in Figure 5, a main effect of valence was found for the diagnosis event. For the birth event, a group × valence interaction was found. Follow-up analyses revealed that the prenatal group reported more positive than negative feeling states about the birth event; valence-related differences were not found for the postnatal group. Participants who received a prenatal diagnosis also reported more positive feeling states and fewer negative feeling states relative to participants who learned of their child's diagnosis after birth.

As shown in Figure S3, a significant time × valence interaction was also apparent. Follow-up analyses conducted by time indicated that participants reported a greater percentage of negative relative to positive feeling states terms at the time of the events, whereas the opposite pattern was found at the time of the study (i.e., participants reported a greater percentage of positive relative to negative feeling states at the time of the study). Follow-up analyses conducted by valence indicated that participants reported a greater percentage of positive feeling states at the time of the study relative to at the time of the events; the opposite pattern was found for negative feeling states, such that participants reported a greater percentage of negative feeling states at the time of the events relative to at the time of the study.

Finally, as shown in Figure S4, a significant time × group interaction was found, but follow-up simple effects analyses yielded no significant differences by either variable.

3.3 Most recent birthday (Table S3)

3.3.1 Maternal ratings

A main effect of time was found for significance, such the child's most recent birthday was more significant when it occurred (5.10 ± 0.24) relative to at the time of the study (4.25 ± 0.27). Significant effects were not found on frequency of thought, frequency of conversation, valence, uniqueness, vividness, maternal confidence that the memory was their own and was not impacted by pictures or conversations with others, and access to pictures.

3.3.2 Internal states language

Although significant effects were not found by group for the total number of words used or the number of cognition terms used, a main effect of valence was found when considering emotion term use, such that participants used more positive (11.97 ± 1.41) relative to negative (3.34 ± 0.71) and neutral emotion terms (2.82 ± 0.61; ps < 0.001), which did not differ.

3.3.3 Feeling states

A main effect of valence was found for feeling states, such that participants reported more positive (0.86 ± 0.03) relative to negative (0.05 ± 0.02) feelings.

3.4 Satisfaction with life

A between-subjects ANOVA conducted by group did not reveal a significant effect on satisfaction with life: F(1, 42) = 0.12, p = 0.736 (prenatal group: 5.21 ± 0.29; postnatal group: 5.08 ± 0.24).

3.5 Correlations between birth story narratives and satisfaction with life

Bivariate correlations were conducted separately by group to examine associations between participant ratings, emotion and cognition language, and feeling states data for the birth stories narratives with satisfaction with life. For participants who received a postnatal diagnosis of DS for their child, participants' confidence that their memories were their own was negatively associated with satisfaction with life: r(24) = −0.42, p = 0.032; significant associations were not found for participants who received a prenatal diagnosis of DS for their child.

4 DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to determine whether mothers differentially reported on the birth and diagnosis of their child with DS based on whether their child was diagnosed during gestation or after birth. As expected based on previous research, few group differences were found on the diagnosis event (Nelson Goff et al., 2013; Staats et al., 2015). In a novel extension, however, participants who received a prenatal diagnosis of DS for their child reflected differently—and seemingly more positively—on their child's birth relative to mothers who received a postnatal diagnosis. These differences were evident when considering participant ratings, emotion language used when discussing the events, and feeling states characterizing how participants felt about the events at the time of their occurrence and at the time of the study.

When considering participant ratings, mothers who received a prenatal diagnosis thought and talked more about their child's birth relative to their diagnosis; the former group also thought more about their child's birth relative to the latter group. Analyses concerning the significance of the events revealed no group differences for the diagnosis event, whereas group differences were found for the birth event. That is, the birth event was similarly significant over time for mothers who received a prenatal diagnosis, whereas that event was more significant at the time of its occurrence relative to at the time of the study for the postnatal diagnosis group. At the time of the study, the prenatal group rated the birth of their child as more significant than the postnatal group. Similarly, the prenatal group more commonly reported that their memories were likely their own and were not influenced by pictures or conversations with others relative to the postnatal group.

The aforementioned effects were replicated in the language and feeling states data. Although group differences were not found in cognition term use, the postnatal diagnosis group used more emotion terms when discussing the diagnosis event relative to the birth event, a finding that was not apparent for mothers who received a prenatal diagnosis. Mothers who received a prenatal diagnosis, however, used more emotion terms when discussing their child's birth relative to mothers who received a postnatal diagnosis. When considering feeling states terms, group differences were not found for the diagnosis event. For the birth event, the prenatal group reported more positive than negative feelings, an effect that was not found for the postnatal group. The prenatal group also reported more positive and fewer negative feelings about the birth event relative to mothers who received a postnatal diagnosis.

The unique patterns of effects observed by group when considering emotion and feeling states terms suggests that the participants processed the birth event differently. Although future work is needed, it is possible that these differences result from between-group variability in the timing of the diagnosis event in relation to the birth experience. That is, mothers who learned of their child's diagnosis during pregnancy not only had more time to process and reflect on the diagnosis relative to mothers who received a postnatal diagnosis, but the diagnosis event was more temporally distant from the birth for the former group relative to the latter. As such, for the prenatal diagnosis group, the negative, emotionally arousing information about the child's diagnosis was temporally separate from the positive, emotionally arousing information about the child's birth, whereas these two events happened in close proximity for the postnatal group. The impact of the timing of the diagnosis is apparent when considering the significance of the events: mothers who received a postnatal diagnosis rated their child's diagnosis as more significant at the time of its occurrence relative to at the time of the study, an effect that was not apparent for mothers who received a prenatal diagnosis; mothers who received a prenatal diagnosis rated the birth event as more significant at the time of the study relative to the postnatal diagnosis group. Although previous work has indicated that mothers prefer to receive news of a potential DS diagnosis even before confirmation is available (for relevant work, see Cunningham & Sloper, 1977; Gayton & Walker, 1974; Pueschel, 1985; Schimmel et al., 2020; Skotko et al., 2009), more nuanced research is needed to better understand how variability in the timing of the diagnosis is associated with maternal reflections on the diagnosis and birth of their child with DS.

In this study, group differences in maternal satisfaction with life were neither apparent, nor were broad associations found between maternal ratings, emotion words use, and feeling states about the birth event and well-being. The one exception is that mothers' confidence that their memories were their own was negatively associated with satisfaction with life for mothers who received a postnatal relative to a prenatal diagnosis. It is unclear why this singular association was statistically significant and should be the subject of future research as a result. Future research should also be conducted to examine whether the relative lack of significant correlations is associated with temporal distancing between the birth of the child and reports of maternal well-being. In this study, these measures were obtained approximately 6 years apart, on average, based on the age of the child with DS at the time of data collection. Longitudinal research should be conducted to determine whether these associations are stronger shortly after the child's birth relative to over the longer term so as to best support new mothers as they adapt to the birth of their child with DS.

Additional work should also examine associations between the emotional nature of the reported events and the content of the memories, particularly in terms of the reporting of central or peripheral details. That is, previous research has shown that emotion may enhance memory for the central details of events and may even serve to impair memory for peripheral details (Levine & Edelstein, 2010). This phenomenon has been documented in laboratory studies (e.g., Christianson & Loftus, 1987; Kensinger et al., 2007) and in ecologically valid contexts (e.g., Bahrick et al., 1998; Christianson & Hubinette, 1993; Sotgiu & Galati, 2007), although not yet in association with mothers' memories for the diagnosis or birth of their child with DS. These associations should be examined in mothers by group, shortly after the birth and diagnosis events as well as over time, to examine how the emotionality of the reported events is associated with memory (e.g., Yegiyan & Yonelinas, 2011) and well-being. Importantly, this longitudinal work should be conducted with diverse groups of participants to ensure generalizability.

Taken together, the conducted research represents a significant extension of the work that has been conducted to date, as we (1) included focus on birth stories in addition to the diagnosis events that have been more commonly analyzed in the literature to date, (2) featured discussion of and ratings on a control event on which the mothers were not expected to differ, and (3) included both quantitative (rating scales) and qualitative measures (analysis of the language mothers used when discussing the events and the distribution of feeling states terms). Given these group differences, medical professionals should carefully consider the conditions under which they provide mothers with diagnostic information and support services after a child is born.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Angela F. Lukowski confirms that she had full access to all the data in this study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Angela F. Lukowski and Jennifer G. Bohanek gave final approval of this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the mothers who participated in this study. We also acknowledge the contributions of post-baccalaureate and undergraduate and research assistants from the UCI INCHES Lab who collected narrative data, processed audio files for transcription, and reviewed transcripts for accuracy before data coding commenced. We thank the laboratory members who provided comments on a draft of this manuscript (Sarah Orsborn, Caleb Schlaupitz, and Xinyi Yu). This study was funded by discretionary monies provided to the corresponding author and undergraduate research awards provided by the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program at the institution at which the data were collected.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

AFL and JGB declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Human studies and informed consent: This research was confirmed as self-determined exempt with the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Irvine. Participants read a waiver of written informed consent (a study information sheet) before participating.

Animal studies: Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Other manuscripts remain to be published from the original narrative data. As such, the de-identified numerical dataset may be requested by qualified individuals from the corresponding author for the purposes of replicating the analyses presented herein.

REFERENCES

- 1 Sliding scales were used to record child functioning at the first session and participant ratings at the second session. When presented to the participant, the slider was presented at the lowest point of the scale (= 1) for questions pertaining to child functioning or at the middle value (= 4) of the scale for event ratings. To register the lowest rating (for child functioning) or a neutral response (for event ratings), the participants had to move the slider off of the number in question and return it to its original location for the data to be recorded. Participants were not aware, however, that they had to move the slider away from—and back to—either the lowest (for child functioning) or the middle response option (for event ratings) for their response to be registered. We reasoned that omitting these data would erroneously bias our findings, resulting in inflated mean values for ratings of child functioning along with greater extreme values (higher and lower) for event ratings. In addition, because participants generally provided complete data on the non-slider questions, we believe that the missing data were actual ratings that were not properly recorded. For these reasons, the following analyses were conducted on a dataset in which the missing slider values were replaced with 0 (for event valence), 1 (for child functioning), or 4 (for frequency of thought, frequency of conversation, event uniqueness, event vividness, and event significance). Information on analyses conducted on the dataset with the missing values included can be obtained from the corresponding author.