BRCA1/2 mutations and risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy among Latinas: The UPTAKE study

Abstract

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) is a risk management approach with strong evidence of mortality reduction for women with germline mutations in the tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2). Few studies to date have evaluated uptake of BSO in women from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds who carry BRCA1/2 mutations. The objective of the UPTAKE study was to explore rates and predictors of risk-reducing BSO among Latinas affected and unaffected with breast cancer who had a deleterious BRCA1/2 mutation. We recruited 100 Latina women with deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations from community hospitals, academic health systems, community, and advocacy organizations. Women completed interviews in Spanish or English. We obtained copies of genetic test reports for participants who provided signed medical release. After performing threefold cross-validation LASSO for variable selection, we used multiple logistic regression to identify demographic and clinical predictors of BSO. Among 100 participants, 68 had undergone BSO at the time of interview. Of these 68, 35 were US-born (61% of all US-born participants) and 33 were not (77% of the non-US-born participants). Among Latinas with BRCA1/2 mutations, older age (p = 0.004), personal history of breast cancer (p = 0.003), higher income (p = 0.002), and not having a full-time job (p = 0.027) were identified as variables significantly associated with uptake of BSO. Results suggest a high rate of uptake of risk-reducing BSO among a sample of Latinas with BRCA1/2 mutations living in the US. We document factors associated with BSO uptake in a diverse sample of women. Relevant to genetic counseling, our findings identify possible targets for supporting Latinas’ decision-making about BSO following receipt of a positive BRCA1/2 test.

What is known about this topic

Deleterious mutations in BRCA1/2 genes are associated with an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer. The uptake of risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy by women with BRCA1/2 mutations has not been fully characterized in racially and ethnically diverse populations.

What this study adds to the topic

We report a high uptake (68%) of risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy among 100 Latinas with BRCA1/2 mutations, similar to previously reported rates in non-Hispanic Whites and considerably higher than what has been described in African Americans.

1 INTRODUCTION

Germline mutations in the tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) are associated with an increased lifetime risk of breast cancer of 40-70% and an increased risk of epithelial ovarian cancer of 15-45% and the development of breast and ovarian cancer at a younger age (Antoniou et al., 2003; Chen & Parmigiani, 2007; Mavaddat et al., 2013; Struewing et al., 1997). Different surveillance and prevention options are available with the goal of early detection and reduction of cancer-related morbidity and mortality (Bradbury et al., 2008; Ludwig, Neuner, Butler, Geurts, & Kong, 2016). Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) decreases the risk of ovarian and peritoneal cancer by 85-96% in BRCA1/2 carriers (Domchek et al., 2010; Kauff et al., 2002; Li et al., 2016; Ludwig et al., 2016; Rebbeck et al., 1999). There is debate whether BSO may also reduce breast cancer risk although the evidence is not conclusive (Eisen et al., 2005; Rebbeck et al., 1999). In BRCA1/2 carriers, BSO is the only management strategy with evidence supporting a reduction in mortality (Finch et al., 2014). Guidelines from several major organizations such as American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend BSO for ovarian cancer risk reduction in BRCA1 carriers by age 35-40 and after completion of childbearing and by age 40-45 in BRCA2 carriers (ACOG, 2017; Lancaster, Powell, Chen, Richardson, & Committee, 2015; NCCN, 2019; Paluch-Shimon et al., 2016). While it is recommended that bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy (BRRM) be discussed with unaffected BRCA1/2 carriers, the impact of this intervention on survival has not been clearly established (Carbine, Lostumbo, Wallace, & Ko, 2018; Ludwig et al., 2016). The NCCN guidelines v1.2020 support discussion of the option of BRRM for these women on a case-by-case basis (NCCN, 2019).

The prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations has not been fully characterized in racially and ethnically diverse populations, including Hispanic/Latino populations in the United States (US) (Bradbury et al., 2008; Cragun et al., 2017). Latinos (referring to individuals from Latin America) are overall the second largest group in the US after Non-Hispanic Whites (NHW), representing about 18% of the total U.S. population, and among the youngest racial or ethnic groups in the US with a median age of 30 in 2018 (Flores, 2017). In a study of 746 Hispanic, primarily Mexican, patients in the Southwestern US with a personal or family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, Weitzel et al identified 124 pathogenic mutations in BRCA1 and 65 in BRCA2 (Weitzel et al., 2013). Interestingly, nine recurrent mutations accounted for 53% of the mutations identified, including a large rearrangement in BRCA1 (del exon 9-12), which is a Mexican founder mutation that represented 62% (n = 13/21) of the rearrangements in their study (Weitzel et al., 2013). However, considerable heterogeneity in the prevalence, presence of founder effects and in the spectrum of pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 has been observed both in the Hispanic/Latino populations of the US and throughout Latin America (Dutil et al., 2015).

The receipt of a positive BRCA1/2 test result will not result in decreased cancer incidence and mortality unless individuals with these mutations undertake risk-reducing measures. The uptake of risk-reducing BSO has been estimated to be between 70 and 80% in NHW populations (Bradbury et al., 2008; K. A. Metcalfe et al., 2008; Schwartz et al., 2012). Prior studies evaluating the uptake of risk-reducing procedures in BRCA1/2 carriers have focused on NHW(Bradbury et al., 2008; K. A. Metcalfe et al., 2008). The limited number of studies with reported results among different racial and groups have included only a small percentage of Latinos (Bradbury et al., 2008; K. A. Metcalfe et al., 2008). Bradbury et al reported an uptake of BSO of 74% in 78 NHW women with BRCA1/2 mutations compared with 40% uptake of BSO in 10 racial and ethnic diverse women (8 African Americans and 2 Latinas) (Bradbury et al., 2008). Cragun et al showed that the uptake of BSO among 90 BRCA carriers was highest in Latinas (90.9%) when compared to NHW (76.6%) or African Americans (28.1%) (Cragun et al., 2017). However, all participants were breast cancer survivors and the number of Latinas with BRCA1/2 mutations was small (n = 11) (Cragun et al., 2017). More recently, Metcalfe et al looked at international trends in the uptake of cancer risk reduction strategies in 6,223 women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation (K. Metcalfe et al., 2019; K. A. Metcalfe et al., 2008). The authors found significant differences in uptake by country although Spain and Latin American countries were not represented (K. Metcalfe et al., 2019; K. A. Metcalfe et al., 2008).

Genetic counseling supports informed decision-making about risk reduction strategies among women with identified BRCA deleterious mutations. As evidenced in the literature, several factors may play a role in decision-making about BSO, including age, family history of ovarian cancer, socioeconomic factors, and specifically for the Latino population, whether information is received in Spanish or English (Cragun et al., 2017; Jagsi et al., 2015). Cragun et al evaluated racial and ethnic disparities in BRCA testing in 1,622 participants and determined that English-speaking Hispanics and NHW were twice as likely to have a discussion of genetic testing with a healthcare provider than compared with Spanish-speaking Hispanics (Cragun et al., 2017). Jagsi et al also found that Spanish-speaking breast cancer patients had the greatest unmet need for discussion of genetic testing (Jagsi et al., 2015). These studies looked at the impact of the language used to discuss genetic testing, but we are unaware of any studies that have explored the role that it might play in surgical decision-making (Cragun et al., 2017; Jagsi et al., 2015).

The primary objective of the UPTAKE study was to explore the rate of risk-reducing BSO among Latinas affected and unaffected with breast cancer who carry deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations living in the US. We also explored factors associated with uptake of BSO. Given that the potential survival advantage associated with BRRM is unclear, we opted to focus solely on BSO. Secondary objectives included characterization of the spectrum of mutations in this cohort, description of Latinas’ satisfaction with BSO decisions and identification of acculturation and attitudinal factors related to uptake of BSO. By understanding the factors associated with increased uptake of BSO, we can identify strategies to help decrease cancer incidence and mortality in Latinas with BRCA1/2 mutations.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study participants

One-hundred women with deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations currently living in the US, who self-identified as Latinas and were 25 years or older participated in this observational study. Women were eligible if they had received BRCA1/2 test results at least one year prior to the date of study enrollment. Women who self-reported prior diagnosis of ovarian cancer or who underwent BSO prior to genetic testing were excluded. We recruited participants nationally from different sources including academic institutions (Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University, Washington DC; University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles County and University of Southern California Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA; Ponce Research Institute, Ponce Health Sciences University, Ponce, PR), Community Practices (Virginia Cancer Specialists, Arlington, VA; Texas Tech Physicians, El Paso, TX), Research Registry Groups (Love Foundation), and Advocacy Groups (FORCE - Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered; Nueva Vida, Alexandria, VA; Latinas Contra Cancer, San Jose, CA; SHARE, New York, NY). Participants were either referred by their treating physician from one of the participating institutions or contacted us directly after learning about this study from advocacy or research registry groups.

2.2 Procedures

All study procedures were approved through the Georgetown-MedStar Oncology Institutional Review Board (IRB). We collected demographic and clinical information through a one-time telephone survey with 63 questions, conducted by bilingual research assistants in the participants’ preferred language (English or Spanish). We used validated scales to assess factors associated with attitudes toward uptake of risk-reducing measures. Scales were either previously validated in Spanish or administered in our prior research in Spanish with Latinas with sound reliability (26). We had multiple bilingual and bicultural members of the team review the survey prior to administration.

Participants provided written informed consent and signed consent for medical record release to review the BRCA1/2 genetic test results. Signed consents were returned to the study team through pre-stamped envelopes. The primary objective was to determine the rate and predictors of uptake of risk-reducing BSO among BRCA1/2-positive Latinas with or without breast cancer. Secondary objectives included description of BRCA1/2 mutations by geographic origin, satisfaction with BSO decision and identification of acculturation, and attitudinal factors related to uptake of BSO. In this manuscript, we report results of the primary objective as well as types of BRCA1/2 mutations identified and degree of satisfaction with the decision made.

2.3 Measures

Demographics. We assessed participants’ self-report of several demographic variables: age, marital status, employment, education, insurance status, geographic origin (place of birth as US vs non-US-born and country of birth for those who were non-US-born).

Personal and Family history of cancer. We assessed participants’ self-report of a personal diagnosis of breast, ovarian, and other cancers, age at diagnosis, and treatment received. Participants also reported family history of cancer [history of breast, ovarian, or other cancers among first- and second-degree relatives and when available, age of diagnosis of relatives’ cancer(s)].

Genetic Services and Risk-Reducing Surgery. We assessed utilization, receipt, and location of genetic counseling, provider language and characteristics, patient language preference, uptake of genetic testing and test result, uptake of risk-reducing BSO (yes/no), and, if yes, date of BSO.

Attitudes and Acculturation. We assessed factors associated with attitudes toward uptake of risk-reducing measures, including perceived risk/concern for recurrence, social stigma and body image concerns, and lack of information about genetic counseling and testing. We assessed acculturation using the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (Baxter et al., 2006; Berrigan et al., 2010; Graves et al., 2008; Marin et al., 1987; Vadaparampil et al., 2010).

Variant nomenclature and classification. Genetic testing results of each participant were requested and reviewed by the study team. Mutation nomenclature was described according to Human Genome Variation Society (den Dunnen et al., 2016). Pathogenicity of the mutations was assessed using ClinVar at NCBI (ClinVar, 2019).

2.4 Data analysis

We summarized characteristics of demographic and clinical variables in the overall sample and whether these variables differed according to BSO uptake. We used descriptive statistics such as frequency and percentage for categorical variables, and median with Q1 and Q3 for continuous variables. We used two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables, Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical variables, and Fisher's exact test when the expected cell count was less than 5 to compare differences between participants who had BSO and who did not.

For the analysis of the primary endpoint, we included a number of possible covariates to identify associations with the uptake of BSO: age at the time of the interview or age at the time of surgery for those who underwent BSO, marital status, household annual income, education, insurance, work status, country of birth, referral to genetic counseling (GC), receipt of GC, language concordance between preferred language and language in which GC was provided, location of GC, personal history of breast cancer, number of first-degree relatives (FDR), and second-degree relatives (SDR) with breast or ovarian cancer, and type of BRCA1/2 mutation (BRCA1, BRCA2, or both). We classified referral to GC into two categories (medical oncologist or surgeon vs others); location of GC was classified into three groups (hospital-clinic, office-private practice, and university-academic center). We handled missing values in language concordance, referral to GC, and location of GC by creating an additional category for missing or unknown values. Missing values for annual income and type of BRCA mutation were replaced with the most common category within each categorical variable, also known as ‘most frequent’. We employed least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) for variable selection and conducted multiple logistic regression with uptake of BSO as outcome and using the variables selected from LASSO. We chose the LASSO approach over the conventional stepwise forward/backward regression approaches because the LASSO approach is well-known to lower prediction errors through cross-validation procedures that can also prevent overfitting. For comparison, we also explored a random forest procedure and used a variance importance plot to display a summary of the variables’ importance ranking among random forest rankings from 500 bootstrap samples. All analysis was performed in RStudio (version 0.99.902).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participant characteristics

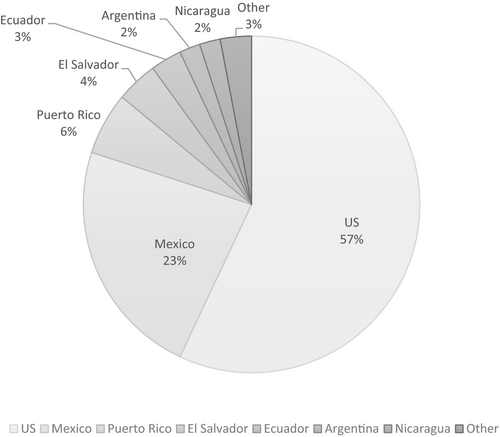

We collected demographic and clinical data from 100 Latinas with deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations currently living in the US (including Puerto Rico). Fifty-seven women identified US as their country of birth, followed by Mexico 23%, Puerto Rico 6%, El Salvador 4%, Ecuador 3%, Argentina 2%, Nicaragua 2%, and other 3% (Figure 1). Demographic information is described in Table 1. At the time of interview, 45 women (45% of sample) were younger than 40 years.

| Overall 100 | Uptake of BSO | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (32) | Yes (68) | |||

| Geographic origin | ||||

| Non-US | 43 (43.0) | 10 (23.3) | 33 ( 76.7) | 0.158 |

| US | 57 (57.0) | 22 ( 38.6) | 35 ( 61.4) | |

| Medical Insurance | ||||

| No | 5 (5.0) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 0.324 |

| Yes | 95 (95.0) | 29 (30.5) | 66 (69.5) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 62 (62.0) | 17 (27.4) | 45 (72.6) | 0.301 |

| Not married | 38 (38.0) | 15 (39.5) | 23 (60.5) | |

| Annual income | ||||

| <50K | 43 (44.3) | 16 (37.2) | 27 (62.8) | 0.568 |

| >50K | 54 (55.7) | 16 (29.6) | 38 (70.4) | |

| Level of education | ||||

| High School or less | 21 (21.0) | 8 (38.1) | 13 (61.9) | 0.681 |

| Some College or more | 79 (79.0) | 24 (30.4) | 55 (69.6) | |

| Job | ||||

| Full time | 53 (53.0) | 24 (45.3) | 29 (54.7) | 0.005 |

| Non-full time | 47 (47.0) | 8 (17.0) | 39 (83.0) | |

| Age at time of survey (median [IQR]) | 46.50 [36.00, 54.00] | 33.50 [28.00, 38.25] | 50.00 [44.75, 56.25] | <0.001 |

| Age combineda | ||||

| <40 | 45 (45.0) | 26 (57.8) | 19 (42.2) | <0.001 |

| ≥40 | 55 (55.0) | 6 (10.9) | 49 (89.1) | |

| Personal history of Breast Cancer | ||||

| No | 38 (38.0) | 22 (57.9) | 16 (42.1) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 62 (62.0) | 10 (16.1) | 52 (83.9) | |

| FDR/SDR diagnosed with BC or OC | ||||

| No | 7 (7.0) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 0.677 |

| Yes | 93 (93.0) | 29 (31.1) | 64 (68.9) | |

| Genetic counseling | ||||

| No | 26 (26.0) | 7 (26.9) | 19 (73.1) | 0.689 |

| Yes | 74 (74.0) | 25 (33.8) | 49 (66.2) | |

| Genetic counseling (language) | ||||

| Spanish | 17 (23.0) | 2 (11.8) | 15 (88.2) | 0.04 |

| English | 57 (77.0) | 23 (40.4) | 34 (59.6) | |

| Language concordance | ||||

| No | 6 (8.1) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 1 |

| Yes | 68 (91.9) | 23 (33.8) | 45 (66.2) | |

| Location of Genetic Counseling | ||||

| Office-private practice | 20 (27.0) | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | 0.057 |

| University-academic center | 27 (36.5) | 9 (33.3) | 18 (66.7) | |

| Hospital-Clinic | 27 (36.5) | 13 (48.1) | 14 (51.9) | |

| Referral for GC | ||||

| Gynecologist | 5 (6.8) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0.458 |

| Multiprovider | 5 (6.8) | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Medical Oncologist | 25 (33.8) | 9 (36.0) | 16 (64.0) | |

| Other | 21 (28.4) | 9 (42.9) | 12 (57.1) | |

| Primary Care Provider | 7 (9.5) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Surgeon | 11 (14.9) | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | |

| BRCA1/2 gene mutation | ||||

| Both | 2 (2.3) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0.918 |

| BRCA1 only | 41 (47.7) | 13 (31.7) | 28 (68.3) | |

| BRCA2 only | 43 (50.0) | 15 (34.9) | 28 (65.1) | |

- BC, breast cancer; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; FDR, first-degree relative; OC, ovarian cancer; SDR, second-degree relative; US: United States.

- a Age at the time of the interview or age at the time of surgery for those who underwent BSO.

3.2 Cancer history and genetic counseling

Sixty-two participants had personal history of breast cancer and 93 reported having at least one first- or second-degree relative diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer. Seventy-four women stated they received GC by a healthcare provider; among those who had GC, 23% (n = 17) reported their counseling was conducted in Spanish, and 91.9% reported that the language in which they received GC was concordant with their personal preference. Most participants were referred for GC by their surgeon or medical oncologist and received GC either in a hospital or an academic setting (Table 1).

3.3 Uptake of risk-reducing BSO and factors associated with decision

Among 100 participants, 68 had undergone BSO at the time of interview, equally distributed between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers (Table 1). Of the 68 women reporting BSO, 35 were US-born (61% of all US-born participants) and 33 were not (77% of the non-US-born participants). The mean age at the time of BSO for US-born participants was 44 (SD 9.2 years) and 47 (SD 9.1 years) for non-US-born participants.

After performing threefold cross-validation LASSO for variable selection, using multiple logistic regression, older age (p = 0.004), personal history of breast cancer (p = 0.003), higher income (p = 0.002), and not having a full-time job (p = 0.027) were identified as variables significantly associated with uptake of BSO (Table 2). Geographic origin, marital status, or having insurance was not selected by LASSO. In random forest analysis, the setting in which GC was provided also became an important factor associated with BSO uptake but was not statistically significant in the logistic model. Based on the potential relationship between income and working full time, we examined the interaction between work status and income using Pearson’s chi-square test; working full time was significantly associated with higher income (p = 0.001).

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal History of breast cancer | 8.28 | (2.0, 33.9) | 0.003 |

| Annual Income> 50K | 12.50 | (2.4, 64.2) | 0.002 |

| Non-full-time job | 4.91 | (1.2, 20.1) | 0.027 |

| Agea (continuous) | 1.13 | (1.0, 1.2) | 0.004 |

| GC location (office vs academic) | 6.7 | (0.93,48.3) | 0.059 |

- BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; GC, Genetic counseling.

- a Age at the time of the interview or age at the time of surgery for those who underwent BSO.

3.4 Degree of satisfaction associated with BSO decision

All 35 (100%) US-born participants who underwent BSO reported being satisfied with their decision to have BSO compared with 26 (79%) of non-US-born participants (p = 0.004). Of the 32 participants who did not have BSO, 31 answered questions related to future plans: 16% (5/31) were considering having BSO within the following year, 71% (22/31) were considering having BSO but had not decided when, 6.5% (2/31) were not sure whether they would have BSO, and 6.5% (2/31) had decided not to have BSO.

3.5 BRCA1/2 mutations and testing results received

By participants’ self-report, 41 reported having a deleterious BRCA1 mutation, 43 a deleterious BRCA2 mutations and 2 reported having both. Fourteen participants did not provide an answer to this question (i.e., whether the BRCA gene was type 1 or 2). We were able to obtain 70 out of 100 genetic testing reports (Tables 3 and 4). Of the 70 participants for whom we were able to obtain results, 55 (79%) reported their results correctly at the time of the telephone survey, 13 (18%) incorrectly reported the type of BRCA1/2 mutation, and 2 (3%) did not provide an answer to the question about test result on the survey. Of these 70 participants, one did not have a deleterious mutation but instead two variants of unknown significance (VUS). Of the 69 women with deleterious mutations, 37 participants had one BRCA1 deleterious mutation and 30 had one BRCA2 deleterious mutation. One participant had a deleterious mutation in each gene, and one had a deleterious mutation in BRCA1 and a VUS in BRCA2. Of the confirmed deleterious mutations, 24 and 22 were identified in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene, respectively. Sensitivity analysis revealed that there were no differences in demographic variables or uptake of BSO between the group of participants that provided access to their genetic testing results (n = 70) and the group who did not provide access to their results (n = 30).

| Variant | Observations (n) | Other names | Country (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| del exon 9-12 | 4 | Mexico (3), US (1) | |

| c.3029_3030del | 4 | 3148delCT | US (3), Mexico (1) |

| c.68_69delAGa | 3 | 185delAG | US (2), Mexico (1) |

| c.5123C> A | 2 | A1708E | US, Mexico |

| del exons 1-2 | 2 | Puerto Rico, Mexico | |

| c.1018C> T | 2 | R1443X | Mexico |

| c.68_69delAG | 2 | US, Ecuador | |

| c.2433del | 2 | 2552delC | US |

| c.5165C> T (VUS) | 2 | S1722Fc, d | US, El Salvador |

| c.3759_3760del | 1 | 3878deITA | US |

| c.4065_4068de | 1 | 4184del4 | US |

| c.5085_5086TG | 1 | 5210delTG | Colombia |

| c.1687C> T | 1 | US | |

| c.2433delC | 1 | 2552delC | US |

| c.4868C> G | 1 | 4987C> G | Mexico |

| c.3675C> A | 1 | 3794 C> A | Mexico |

| c.115T> A | 1 | C39S | US |

| c.1018C> T | 1 | 4446C> T | US |

| del 22-23 | 1 | US | |

| E29X | 1 | Mexico | |

| EX21_3'UTRdel | 1 | El Salvador | |

| c.1687C> Tb | 1 | Q563X | US |

| c.3083G> A (VUS) | 1 | R1028Hc | US |

| c.4484G> T | 1 | R1495M | US |

| c.5251C> T | 1 | R1751X | Mexico |

| c.5154G> A | 1 | W1718X | US |

- In gray: VUS or polymorphisms.

- US, United States; VUS: variant of unknown significance.

- a Participant with one BRCA1 deleterious mutation (185delAG) and one BRCA2 deleterious mutation (4859delA).

- b Participant with one BRCA1 deleterious mutations and one BRCA2 VUS.

- c Participant with two VUS in BRCA1.

- d Initially diagnosed as VUS and later reclassified as a deleterious mutation.

| Variant | Observations (n) | Other names | Country (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| c.3264dupT | 5 | 3492insT | Mexico (4), US (1) |

| C.3922G> T | 3 | E1308X | Puerto Rico (2), US(1) |

| c.145G> T | 2 | E49X | US, Mexico |

| c.5799_5802del | 2 | 6027del4 | US |

| c.6937 + 594T>G | 2 | US | |

| c.7007G> A | 2 | 7235G> A | Argentina |

| c.1302_1305AAGA | 1 | 1538del4 | US |

| c.1511_1512del | 1 | 1739delCT | Bolivia |

| c.2808_2811del | 1 | 3036del4 | US |

| c.5073dupA | 1 | 5301insA | US |

| c.5542del | 1 | 5770delA | Mexico |

| c.6078_6079dela | 1 | 6306delAA | Mexico |

| c.6877T> Ca (Polymorphism) | 1 | F2293L (7105T> C) | Mexico |

| 6392delT | 1 | 6392delT | US |

| c.6482_6485ACAA | 1 | 6714del4 | US |

| c.145G> T | 1 | US | |

| c.4740_4741dupTG | 1 | US | |

| c.5722_5723del | 1 | US | |

| c.6275_6276delTT | 1 | 6503delTT | Dominican Republic |

| c.9026_9030del | 1 | 9254del5 | El Salvador |

| c.652G> T | 1 | E218X | US |

| c.7757G> A | 1 | W2586X | Mexico |

| c.4631delb | 1 | 4859delA | Mexico |

| c.7435 + 6G>Ac (VUS) | 1 | IVS14 + 6G>A | Mexico |

- In gray: VUS or polymorphisms.

- VUS, variant of unknown significance; US, United States.

- a Participant with deleterious mutation and polymorphism of BRCA2.

- b One participant (from Mexico) had BRCA1 mutation 185delAG and BRCA2 4859delA.

- c Participant with BRCA1 mutation Q563X and BRCA2 VUS IVS14 + 6G>A.

4 DISCUSSION

To date, this is the largest study evaluating the uptake of risk-reducing BSO among BRCA1/2-positive Latinas who live in the United States. Our study demonstrates a high uptake rate of 68% of BSO in this population. These results expand similar findings from studies with much smaller numbers of Latinas (Bradbury et al., 2008; K. Metcalfe et al., 2019; K. A. Metcalfe et al., 2008). In the present study, age, personal history of breast cancer, and economic factors (job and income) were statistically significantly associated with the uptake of BSO. Previous studies have shown that age, personal history of breast cancer, and higher income were associated with higher uptake of this prophylactic measure (Bradbury et al., 2008; K. Metcalfe et al., 2019; K. A. Metcalfe et al., 2008). In this study, although the variables of having a full-time job and having higher annual income were positively correlated with one another (p = 0.001), these variables had contrasting relationships with the uptake of BSO. Specifically, women not employed full time were more likely to have BSO than women employed full time, possibly explained by an increased availability to obtain medical care, even though higher income was also associated with uptake of BSO. These opposing relationships may be explained by the small sample size, which is a limitation of this study.

Our results suggest similar rates of BSO between Latinas who participated in our study and NHW BRCA1/2 carriers mainly based at academic institutions (Bradbury et al., 2008; K. Metcalfe et al., 2019; K. A. Metcalfe et al., 2008; Schwartz et al., 2012). However, the rate of BSO in this cohort was considerably higher than what has been described in African American BRCA1/2 carriers (Bradbury et al., 2008; K. Metcalfe et al., 2019; K. A. Metcalfe et al., 2008; Schwartz et al., 2012). This finding suggests that various cultural and socioeconomic factors may underlie attitudes about risk-reducing surgeries and these attitudes and risk management behaviors may vary in different racial and ethnic groups. In an international study that included women from ten countries (Austria, Canada, China, France, Israel, Italy, Norway, Holland, Poland, and US), 64.7% of the BRCA1/2 carriers underwent BSO (K. Metcalfe et al., 2019). As expected, there were significant differences among countries, with BSO uptake being highest in France (83.3%) and lowest in China (36.7%), further contributing to a growing body of evidence that shows that cultural, social, and perhaps medical access factors may influence BSO decisions and outcomes (K. Metcalfe et al., 2019). We add to this emerging literature with the results from our study the novel finding that the level of satisfaction with undergoing BSO differed between US-born and non-US-born participants. Possible explanations for the lower level of satisfaction with BSO among non-US-born participants include barriers due to language, discomfort with questioning the provider about risk management options due to ‘respecto’ (not wanting to challenge figures of authority like physicians), or negative effects of BSO on body image. Future research can explore these differences in satisfaction by examining the reasons behind satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

We reported a diverse spectrum of BRCA1/2 deleterious mutations detected in the 70 participants with results confirmed through formal genetic test reports. Three recurrent mutations accounted for 28% of all detected BRCA1 mutations (ex9-12del, 3148delCT, and 185delAG). Deletion of exons 9-12 was found mainly in patients from Mexico and has been reported as a Mexican founder mutation by Weitzel et al in (2012) and by Villarreal-Garza et al. (2015) (Villarreal-Garza et al., 2015; Weitzel et al., 2013). These investigators found that deletion of exons 9-12 accounted for 10% and 33% of the BRCA1 mutations all in patients of Mexican ancestry (Villarreal-Garza et al., 2015; Weitzel et al., 2013). BRCA1 3148delCT has also been reported as a recurrent BRCA1 mutation in the Hispanic population (Nahleh et al., 2015). The Ashkenazi Jewish mutation BRCA1 185delAG was reported in three participants (Rosenthal, Moyes, Arnell, Evans, & Wenstrup, 2015). BRCA2 3492insT was identified in five patients, mostly of Mexican origin, which has been previously described (Torres-Mejia et al., 2015). BRCA2 E1308X was the second most frequently reported mutation in this gene, in two participants from Puerto Rico, where this mutation has been previously reported, as well as in Spain (Diaz-Zabala et al., 2018; Duran, Esteban-Cardenosa, Velasco, Infante, & Miner, 2003). In this large group of Latinas with known BRCA1/2 mutations, we were unable to detect a pattern of multiple recurrent mutations as previously reported in a sample of Hispanics of predominantly Mexican origin. Our results likely reflect the heterogeneity of our population with different geographic origins and possible contribution of other genetic heritage (Struewing et al., 1997). Of concern, 1 of 70 participants did not have a deleterious mutation and 13 (18%) reported incorrectly their specific type of BRCA mutation. Women’s lack of knowledge of their type of mutation (BRCA1 vs 2), and understanding of whether it is deleterious or not could impact the decision and timing of uptake of risk-reducing measures and awareness of increased risk of other malignancies.

The UPTAKE study was unique as it included participants from across the US with different countries of origin, income, level of education, and language preference. As we recruited Latinas from various academic and community centers, our sample is likely more reflective of the overall Latino population living in the US rather than only a specific group of Latinas. Finally, we were only able to obtain 70% of the genetic testing results which is consistent with other studies (Cragun et al., 2017). Importantly, sensitivity analysis regarding missing data did not reveal differences in the uptake of BSO between the participants who did and did not provide reports of genetic testing results.

The results of this study are meaningful for genetic counselors who provide services to the Latina population. This study highlights the importance of providing a copy of testing results and interpretation summary to patient and their doctors, encourage patients to keep a copy of the results and emphasize that VUS results are not the same as pathogenic variants. In addition, genetic counselors should assess potential barriers to BSO (cost, time off from work, childcare, effects of becoming postmenopausal earlier than natural age) and identify support resources to facilitate informed uptake of BSO among diverse populations.

4.1 Study limitations

This study had several limitations, such as ascertainment bias as participants were referred from support groups and academic centers that are likely to reinforce the uptake of risk-reducing strategies, and the perspective of women declining or delaying surgery may not be well represented. Although we consider the broad reach of our recruitment approach as a strength, we were not able to identify how many women did not meet eligibility criteria (e.g., women who reported a personal history of ovarian cancer). Most participants in our study had history of breast cancer which may have also affected our results. While this cohort is diverse, the majority of respondents were US-born, almost 80% had at least some college education, and most reported having insurance coverage. Given that Latinas in the US are a very heterogeneous group from country of origin, to cultural identification, and access to care, further studies are needed to explore the nuisances and predictors of decision-making. In addition, failure to collect data on timing between receipt of BRCA testing results and date of BSO may have affected our results as this is likely to influence decision-making. Finally, given the cross-sectional nature of the study design, information other than genetic test result was collected through participants’ self-report.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In summary, in this study of 100 Latinas with BRCA1/2 mutations currently living in the US, we report a high uptake of risk-reducing ovarian cancer surgery. We also present a diverse panel of BRCA1/2 mutations in this cohort, including large rearrangements. Unique factors associated with BSO uptake were identified in this cohort of Latinas. By better understanding the factors associated with BSO uptake, we can develop interventions to promote informed decisions and encourage risk reduction surgery for consequent reduction in cancer incidence and mortality.

PREVIOUS PRESENTATIONS

The results of the UPTAKE study have been partially presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, December 2017.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Filipa Lynce, Claudine Isaacs, and Kristi Graves: contributed to conception and design. Filipa Lynce, Ilana Schlam, Xue Geng, Beth N. Peshkin, Jaeil Ahn, Claudine Isaacs, and Kristi Graves: contributed to data collection, analysis, and interpretation. All authors: contributed to manuscript writing; approved the final manuscript; are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

Financial Support: This study was supported by an American Cancer Society (ACS) Institutional Research Grant, Identifying Number: 2015 – 2016 (NCE), GR 411788 and P30CA051008 (PI: Weiner) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Additional contributions: We would like to thank Adriana Serrano, Paola Rodriguez for conducting telephone interviews and Ivis Sampayo, Ysabel Duron, Victor Priego, and Regina Hampton for referring participants for this study.

Conflict of interests

Filipa Lynce discloses reimbursement for advisory board participation for Pfizer, participation in advisory board for Astra Zeneca (non-remunerated) and research grant to her Institution from Pfizer and Tesaro. Neelima Denduluri discloses research funding for her Institution from Pfizer. Claudine Isaacs discloses reimbursement for advisory board participation for Pfizer and Astra Zeneca, and research grant to her Institution from Tesaro. Ilana Schlam, Xue Geng, Beth N. Peshkin, Sue Friedman, Julie Dutil, Zeina Nahleh, Claudia Campos, Charité Ricker, Patricia Rodriguez, Jaeil Ahn, and Kristi D. Graves declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human studies and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Animal studies

No non-human animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Disclaimer

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the American Cancer Society or the National Institutes of Health.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.