The impact of health anxiety on perceptions of personal and children’s health in parents with Lynch syndrome

Funding

This study was funded by a Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to Dr. Albiani and a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to Dr. Hart.

Abstract

This study examined the differences in perceptions of one's health and one's child's health between parents with Lynch syndrome (LS) characterized with high versus low health anxiety. Twenty-one parents completed semistructured telephone interviews about their perceptions of their own health and the health of their children. Qualitative content analysis using a template coding approach examined the differences between parents with high and low health anxiety. Findings revealed that the most prevalent difference emerged on perceptions of personal health, showing individuals with high health anxiety reported more extreme worries, were more hypervigilant about physical symptoms, experienced the emotional and psychological consequences of LS as more negative and severe, and engaged in more dysfunctional coping strategies than those with low health anxiety. Unexpectedly, with regards to perceptions of their children, parents in the high and low health anxiety groups exhibited similar worries. However, high health anxiety parents reported using dysfunctional coping about their children's health more frequently than those with low health anxiety. The findings suggest that health anxiety is of clinical significance for individuals with LS. Accurately identifying and treating health anxiety among this population may be one avenue to reduce the distress experienced by LS carriers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Lynch syndrome (LS) is an autosomal dominant cancer predisposition condition caused by germline pathogenic variants in the mismatch repair (MMR) genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, or terminal deletions in EPCAM. Individuals with LS are at an increased risk of multiple cancer types, although lifetime cancer risks vary by gene. These cancers include colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, urothelial, small intestine, stomach, hepatobiliary, brain, and sebaceous cancers (Win et al., 2012). Prevalence of LS in the general population also varies, but it has been estimated that 1/200–1/400 individuals may carry a germline MMR pathogenic variant (Chen et al., 2006; Haraldsdottir et al., 2017). Identifying indviduals with LS to implement cancer surveillance such as routine colonoscopy and opportunities for preventative surgery, including prophylactic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingoophorectomy, is important (Gupta et al., 2017). Moreover, identification of individuals with LS has implications for their relatives. All first-degree relatives of someone with LS are at 50% risk of also carrying the pathogenic variant and would be eligible for high-risk screening and surgery (Lynch et al., 2009).

Although most people adapt well to a LS diagnosis (Galiatsatos, Rothenmund, Aubin, & Foulkes, 2015), health anxiety is a common correlate of living with hereditary cancer (e.g., Watson et al., 1999). Health anxiety is defined by heightened fear or worry about ill health (Salkovskis & Warwick, 1986). High health anxious people misinterpret benign physical sensations as signs of disease, overestimating the probability of serious illness and perceiving physical symptoms to be dangerous (Warwick & Salkovskis, 1990). Health anxiety has been shown in prior research to be a long-lasting problem. For example, a longitudinal study showed that the proportion of primary care patients with high health anxiety at baseline was 59.3% and at 2 years later it was 45.3%, demonstrating that very few patients with high health anxiety spontaneously remit in their symptoms (Fink, Ørnbøl, & Christensen, 2010). Similarly, Fernàndez and colleagues (Fernàndez, Fernàndez, & Amigo, 2005) reported persistent health anxiety in primary care patients over a 1 year period, and suggested that health anxiety has trait-like features. Although health anxiety can fluctuate over time, it generally remains stable even over the course of 4–5 years (Barsky, Fama, Bailey, & Ahern, 1998). Importantly, a diagnosis of a medical condition seems to heighten the risk of health anxiety; Sunderland, Newby, and Andrews (2013) reported in a population-based study that participants with at least one medical illness were 4.67 times more likely to meet criteria for health anxiety.

Health anxiety may also lead to worry about one's children, although little research has examined the spillover of health anxiety from self to child in people with LS. In one study of individuals undergoing genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) or LS, 19% reported experiencing unwanted changes in family relationships such as increased feelings of guilt toward children, difficulties with communication, and imposed secrecy (Van Oostrom et al., 2006). Relatedly, research shows parents who are carriers of a genetic predisposition to cancer experience anxiety about their child's health and also worry about their child developing cancer in the future (Bartuma, Nilbert, & Carlsson, 2012). For parents who have already been diagnosed with cancer, fears regarding their children's health may be further amplified. For example, in a study examining carriers of LS or HBOC who had a cancer diagnosis, 80% expressed concern over their children's future health. In particular, parents worried about their child inheriting their pathogenic variant and developing cancer (Bonadona et al., 2002). Given current age guidelines for predictive LS genetic testing, parents of young children and adolescents rarely receive confirmation of their child's carrier status (Ross, Saal, David, & Anderson, 2013). For LS parents with high health anxiety, this ambiguity and uncertainty may particularly increase distress and hypervigilance toward their child's health. Hypervigilance and distorted cognitions about health are hallmarks of health anxiety (Warwick & Salkovskis, 1990), and as such, it is not unreasonable to believe that parents with heightened health anxiety may experience a similar process with regards to their children's physical symptoms and health. Therefore, we hypothesized that parents with elevated health anxiety would experience exacerbated negative reactions about both their own health as well as their children's health. Although parents with LS may be at risk for experiencing distress above and beyond people without offspring, the impact that health anxiety has on parental perceptions of one's own health and one's child's health has yet to be examined.

2 METHODS

This qualitative study examined the impact of health anxiety on the experience of being a parent who has LS. Specifically, low and high health anxious parents were interviewed to examine differences in the experience of being a parent with LS and perceptions of their children's health. These interviews were conducted in 2013 with a subset of participants who had previously completed a larger, mixed-methods study of health anxiety (N = 209 adults with LS). In brief, this larger study recruited participants from the Familial Gastrointestinal Cancer Registry at the Zane Cohen Centre for Digestive Diseases (Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto). All participants had a germline MMR pathogenic variant causing LS and completed a cross-sectional self-report questionnaire about living with LS. All study procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Board at Mount Sinai Hospital and Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada and were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

2.1 Participants

To be eligible for this qualitative study, the participant must have had: (1) completed the larger questionnaire study of health anxiety described earlier, (2) a minimum of one biological child, and (3) a health anxiety score below the 10th or above the 90th percentile of the total sample range of scores as measured by the 14-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI) (Abramowitz, Deacon, & Valentiner, 2007; Salkovskis, Rimes, Warwick, & Clark, 2002). The SHAI is a commonly used self-report measure designed to assess the full continuum of health anxiety, ranging from low health anxiety to hypochondriasis. It was developed to minimize inflation of health anxiety scores among people who have medical illnesses and has been shown to be psychometrically sound in over 40 studies, as examined by Alberts, Hadjistavropoulos, Jones, and Sharpe (2013). In the larger questionnaire study, the mean total score was 13.68 (SD = 6.98) and total range of scores was 0–38 (of a total possible range of 0–42). Twenty-one individuals were identified whose scores fell below the 10th percentile and 21 individuals were identified whose scores fell above the 90th percentile of the SHAI. Two subgroups were created to qualitatively analyze and compare the experiences of parents with high and low health anxiety. Groups were equally matched on gender.

2.2 Procedure

Participants from the aforementioned larger study were contacted via telephone and informed that they had been selected to participate in a 45–60 min qualitative telephone interview. The selected participants were rank ordered according to their scores, and called in descending order for the high anxiety sample and ascending order for the low anxiety sample. Interviews were conducted, on average, 3 months after participation in the larger study. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants. Interviews were audio recorded and conducted by the first author and a trained research assistant. Participants received a gift card for their participation.

In total, 27 individuals were called for interviews. Four individuals could not be reached and one person declined participation because of time constraints, leaving 22 people who completed interviews (81.5% response rate). One interview was discarded due to inadequate English language proficiency. Interview audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and uploaded to the qualitative analysis program NVivo 9.0.

2.3 Qualitative lens

This study drew from both a pragmatic and phenemological lens to guide question development, data analysis, and interpretation. Pragmatism was selected because it recognizes the need to explore and describe real-world experiences and problems using a practical approach, often leading toward action (Dures, Rumsey, Morris, & Gleeson, 2011). In the current study, we were looking to develop functional knowledge to address the gap in the literature on the role of health anxiety in the experiences of parents living with LS. In addressing this gap, we were looking specifically for knowledge on the experience of being an individual living with LS and also as a parent with LS. For this gap, we drew from a phenemological approach focusing on understanding how individuals make meaning of their life experiences, and in the current study how they have experienced living with LS (Smith, 2011). Phenemological approaches have also been previously used in a number of studies examining the lived experience of patients with cancer (e.g., Reynolds & Lim, 2007).

2.4 Coding process

The coding was undertaken by the lead author and a trained research assistant with support from two senior researchers. The senior researchers had complementary expertise; one in health anxiety and LS, and the other with qualitative research and well-being but who was not involved in any other aspect of the larger aforementioned study. All members of the research team completed training in qualitative research through either a course or directed readings, with the emphasis on understanding the researcher's role, risk for bias, thematic analysis, and reflexivity. Upon completion of training, the principal coders (lead author and research assistant) met on a weekly basis throughout the coding process and engaged in peer debriefing as recommended by Creswell and Miller (2000). They also met with the senior qualitative researcher biweekly and the senior health researcher monthly. These latter meetings were designed to identify biases in interpretation, to discuss working hypotheses and formulations, to check the appropriateness of themes and interpretations, and to engage in checks to validate the data interpretation. This process has been identified as a method to establish trustworthiness (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) and was further complemented with an auditing process wherein the principal coders brought in their coding documents to discuss with the senior researchers. The auditing procedure followed guidelines put forth by Huberman and Miles (1998). Any bias as a result of power imbalance between the principal investigator and research assistant as coders was mitigated through training, regular meetings, and the inclusion of two senior researchers who could independently respond to concerns raised by the coders.

2.5 Thematic analysis

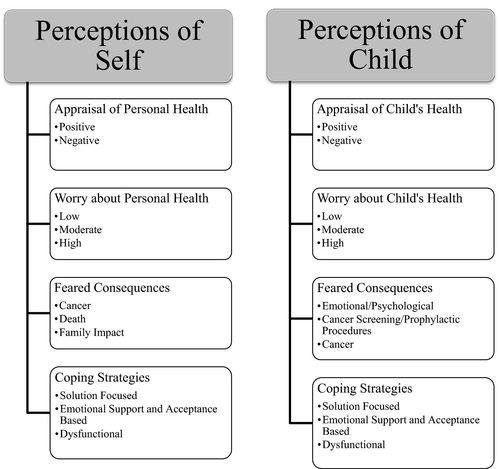

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), following the 15-item criteria list of good thematic coding. In the first phase, transcribed interviews were read independently by principal coders and notes were taken on salient ideas within the texts. In the second phase, the initial codes were identified from a theory-driven approach. This draft codebook was created prior to study initiation based primarily on the health anxiety model (e.g., Warwick & Salkovskis, 1990), which contained the codes that were expected to emerge. This draft theory-derived codebook was then supplemented with a data-driven approach where principal coders incorporated the ideas and codes from the first phase into this drafted codebook. In the third phase, codes were examined for similarities to identify overarching themes. In the fourth phase, a thematic map of the analysis was created to capture both the codes and the themes (see Figure 1). The focus of the fifth phase was to refine the naming of the themes and provide definitions that were detailed and succinct, and represented the specific details included in each theme. In the sixth and final phase, emphasis was placed on the written presentation of the thematic map, themes and codes that were created in the coding process.

The thematic analysis process took place over 5 months and included meetings with the research member members described earlier. With respect to ensuring saturation in responses was attained, the coding process began prior to the completion of the interview process. As there are no preset criteria to follow for establishing saturation (Mason, 2010), a pragmatic approach of coding five interviews at a time was employed to allow for checks of saturation in blocks. The first three phases of the thematic analysis took place for five transcripts at a time. Once the thematic map was established in the fourth phase, it was used to guide the coding process for the next block of five transcripts. After reviewing 20 transcripts, no new themes or codes were identified by the researchers. Thus, the interviews were completed after the last scheduled interview (participant 21).

As the interviewers were also coders of the data, the status of the participant (i.e., high vs. low health anxiety) could not be concealed. Data were organized based on the codes by participant group (i.e., high vs. low health anxiety) to examine differences.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sample characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and medical information stratified by low (6 men, 5 women) and high (5 men, 6 women) health anxiety. Participants were primarily Caucasian (90.5%), employed (66.7%), and college educated or higher (66.6%). All were married or partnered (100%; mean length of relationship 22.2 years, SD = 10.32 years). The mean age was 51.2 years (SD = 10.6). Table 2 shows the sample medical characteristics. The mean time since participants had been diagnosed LS was 5.74 years (SD = 3.83). Over 60% had been diagnosed with cancer in their lifetime, with the mean time since first cancer diagnosis at 12.1 years (SD = 7.2) and the mean time since most recent cancer diagnosis at 8.8 years (SD = 6.0). For those with low health anxiety, two people had never been diagnosed with cancer, six people had been diagnosed with one cancer (colon), and two people had been diagnosed with two cancers (colon, plus duodenum or endometrial). Among the high anxiety group, six people had never been diagnosed with cancer, four had been diagnosed with one cancer (colon, rectal, or breast), and one diagnosed with three cancers (bladder, ovarian, and endometrial). On average, participants had 2.38 children (SD = 1.16) and 52.4% had at least one child under age 18. Of the 29 children presumed eligible to receive genetic testing for LS, 17 (58.6%) had genetic counseling and testing for LS, and nine were determined to have the known familial pathogenic variant. Among the low health anxiety group, of 26 children (age range 9 to 42 years old), 18 children were over age 18, nine had genetic counseling and testing for LS and six had the known familial pathogenic variant. Among the high health anxiety group, of 24 children (age range 4–40 years old), 11 were over age 18, eight had genetic counseling and testing for LS, and three had the known familial pathogenic variant.

| Variable | Low health anxiety group (n = 10) | High health anxiety group (n = 11) | Total (N = 21) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | ||||

| Age (years) | 53.2 (9.8) | 49.36 (11.5) | 51.2 (10.6) | ||||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 5 (50.0) | 5 (45.5) | 10 (47.6) | ||||||

| Female | 5 (50.0) | 6 (54.5) | 11 (52.4) | ||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 10 (100) | 9 (81.8) | 19 (90.5) | ||||||

| Employment | |||||||||

| Full-time | 7 (70.0) | 4 (36.4) | 11 (52.4) | ||||||

| Part-time | 1 (10.0) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (14.3) | ||||||

| Retired | 2 (20.0) | 1 (9.0) | 3 (14.3) | ||||||

| Disability | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.0) | 1 (4.8) | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0 (0.0) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (14.3) | ||||||

| Annual income | |||||||||

| 0–40 K | 4 (40.0) | 1 (9.0) | 5 (23.8) | ||||||

| 40–75 K | 5 (50.0) | 4 (36.4) | 9 (42.9) | ||||||

| >75 K | 1 (10.0) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (28.6) | ||||||

| Education | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 3 (30.0) | 3 (27.3) | 6 (28.6) | ||||||

| Some college | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | ||||||

| College | 5 (50.0) | 7 (63.6) | 12 (57.1) | ||||||

| Graduate/professional | 1 (10.0) | 1 (9.0) | 2 (9.5) | ||||||

| Married or Partnered | 10 (100) | 11 (100) | 21 (100) | ||||||

| Variable | Low health anxiety group (n = 10) | High health anxiety group (n = 11) | Total (N = 21) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age at first cancer diagnosis (years) | 43.1 (8.3) | 43.4 (6.1) | 43.1 (8.3) |

| Number of cancer diagnoses | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.7) |

| Time since first cancer diagnosis (years) | 13.1 (8.5) | 10.4 (4.8) | 12.1 (7.2) |

| Time since most recent cancer diagnosis (years) | 9.3 (6.6) | 8.2 (5.8) | 8.8 (6.0) |

| Time since LS diagnosis (years) | 5.3 (2.7) | 6.1 (4.7) | 5.74 (3.8) |

| Time since diagnosis of first cancer or LS (years) | 12.3 (8.3) | 9.0 (5.2) | 10.7 (7.0) |

| Number of all relatives diagnosed with cancer | 14.8 (11.5) | 18.3 (9.5) | 16.6 (10.4) |

| Number of all relatives deceased from cancer | 7.6 (5.5) | 11.4 (7.1) | 9.5 (6.4) |

3.2 Thematic map

The thematic map shown in Figure 1 was organized into two main domains: (1) Perceptions of Self and (2) Perceptions of Child. The Perceptions of Self category focused on how participants viewed their health and future and the impact of LS on their anxiety. This category contained four main themes (Appraisal of Personal Health, Worry about Personal Health, Feared Consequences, and Coping Strategies) and had 11 codes.1 The Perceptions of Child category examined parents’ evaluation of their children's health and the impact of this worry. This category contained four themes (Appraisal of Child's Health, Worry about Child's Health, Feared Consequences, and Coping Strategies) and had 11 codes.

3.3 Main findings

Domain 1: Perceptions of self

This category focused on how participants viewed their health and future, their perceived vulnerability to illness, and perceptions of how they viewed their health as compared to the health of their peers.

Appraisal of personal health

I have no problems with heart, I have no problems with the lungs, I have no problems with my physical conditions. No, I'm – I would say that I'm a very healthy person. (ID 13, low health anxiety male, prior colon cancer).

Worry about personal health

I know I have my colonoscopies every six months, but I don’t worry about it. If they find something, they find it and it’s early detection so we can do something about it but it’s not daily. (ID 14, low health anxiety female, prior colon cancer)

I worry daily… when my body is feeling a little different. I’m always, my mind always goes to cancer…if my stomach is bothering me then I would look and think, “is that?” or “should I go for a test?” “should I ask for another test?” (ID 2, high health anxiety male, no prior cancer)

Feared consequences

Participants spontaneously discussed three feared consequences of LS: (1) Cancer, (2) Death, and (3) Family Impact. Interestingly, both groups discussed all three of these categories, however, worries for those with high health anxiety were much more extreme.

Cancer

The high health anxiety participants spoke of their fear of developing cancer, and had a tendency to focus on a specific type of cancer or on a bleak prognosis. However, the low health anxiety group tended to note the possibility of being diagnosed with cancer as a potential future outcome and did not dwell on the consequences of the diagnosis. In fact, they viewed the diagnosis as manageable, for example, “If I do have a recurrence of cancer if it's in the colon at least it's in a place that you can remove it.” (ID 12, low health anxiety male, prior colon cancer).

Death

When you’re diagnosed with something like Lynch syndrome you have to get used to the idea of living with it because there was actually a period of time where I had started planning my funeral. In the beginning I was preparing to die, not to live. (ID 3, high health anxiety female, prior endometrial, bladder, and ovarian cancer)

Family impact

And that’s what gives you strength is I refuse to let him grow up without a mother. So you play little games in your mind, like when I was diagnosed I kept saying oh God, let me live until at least he finishes school. (ID 8, high health anxiety female, prior breast cancer)

One thing I’m thankful for is I have excellent death benefits and pension at work…Of course they would miss me but at least they’d be okay financially. And we’re close with our family so there’s lots of people around to give support that way as well. (ID 12, low health anxiety male, prior colon cancer)

Coping strategies

Coping strategies were grouped into three categories based on Carver, Scheirer, and Weintraub's (1989) coping framework: (1) Solution-Focused Coping (e.g., becoming informed about LS), (2) Emotional Support and Acceptance Based Coping (e.g., seeking emotional support from loved ones, positive reappraisal of the situation, acceptance of the situation), and (3) Dysfunctional Coping (e.g., denial, avoidance, rumination, self-blame). These three aspects of coping are derived from the extensive literature on coping with stressful life events and are empirically supported (Carver et al., 1989). Therefore, these categories served as a framework from which to code participants’ responses regarding managing worry and uncertainty about LS.

Solution focused coping

Well I did a lot of research. And I figured that the more I know, the less I worry… I think people fear the unknown more than anything…But if I know the situation, it’s not as bad as I thought it was then I feel a lot better. (ID 1, low health anxiety male, prior colon cancer)

As well, both groups of participants discussed making healthy lifestyle changes (e.g., quitting smoking) and attending regular cancer screening appointments: “I go for my testing when I'm supposed to go then it frees my mind of any other thought where, if I didn't go for the testing I would kind of wonder what was going on.” (ID 2, high health anxiety male, no prior cancer).

Emotional support and acceptance based coping

Even when I got sick when the boys were little kids, my friends took over and I didn’t need to worry about the children. (ID 3, high health anxiety female prior endometrial, bladder, and ovarian cancer).

I guess the biggest thing that I’ve learned is that the hardest thing to learn is that I can’t control this, like I can’t change it. There are some things as you’re an adult you realize you can’t change; you have no control over it. (ID 4, high health anxiety female, no prior cancer)

Dysfunctional coping

The groups differed most on use of dysfunctional coping strategies. In fact, no items were coded as dysfunctional coping for the low health anxiety group. Although dysfunctional coping was the least frequently endorsed, the majority of high health anxiety participants engaged in catastrophizing about the future, avoidance, and rumination, for example:

I’m more of a realist, I look to the worst possible scenario. I guess that’s my coping mechanism, because if the worst doesn’t happen I feel like I got a bonus. (ID 3, high health anxiety female, prior endometrial, bladder, and ovarian cancer)

Yeah, I spend a lot of time trying not to think about it. And then talking about it just forces me to think about it, so I avoid that. (ID 5, high health anxiety female, no prior cancer)

I think when I first found out I think I probably festered about it and there’s dwelling on it for days. (ID 4, high health anxiety female, no prior cancer)

3.3.1 Domain 2: Perceptions of child

The Perceptions of Child category examined parents’ evaluation of their children's health and the impact of this worry.

Appraisal of child's health

Unexpectedly, no differences were observed between groups on perceptions of their children's health. Children's health was described as quite positive, with only a few instances of health problems and no mention of LS. In the few instances that parents described their child's health negatively, it was related to discrete problems (e.g., allergies, obesity, psoriasis).

Worry about child's health

Of course I worry…he has some migraine headaches which kind of attack him every now and then but that’s something else… that’s nothing to do with the genes for colon cancer. (ID 6, high health anxiety male, prior colon cancer)

Recently my daughter has started to get headaches. I had a relative who had brain cancer. So they sent her for an MRI and everything turned out fine but until you get that final notice… I worry because I know she is [worrying]. (ID 7, low health anxiety male, prior colon cancer)

I hate that my mind goes there, but he’s young…So when he’s complaining, [cancer] is the first thing that bounces into my mind …I grill him a little deeper than probably most parents would because I am so aware of what we are predisposed to. (ID 8, high health anxiety female, prior breast cancer)

With my kids especially, the one who was really sick especially, I worry constantly. When something bad does happen I elevate from regular/normal to panic instantly. I’m not an anxious person on a regular basis but I’m nervous. Does that make sense? (ID 9, low health anxiety female, no prior cancer)

Feared consequences

Parents discussed three categories of fears of their children being diagnosed with LS: (1) Emotional/Psychological, (2) Cancer Screening/Prophylactic Procedures, and (3) Cancer.

Emotional/psychological

I would feel worried for them. Knowing what I go through every 18 months and what I have to do… If they could handle the same thoughts that go through my own head. (ID 2, high health anxiety male, no prior cancer)

[What bothers me most] is just to know that they have to live with that constant wonder if they’re going to get cancer or not. (ID 10, high health anxiety female, no prior cancer)

Cancer screening/prophylactic procedures

Having colonoscopies from 21 on, and having to worry about cervical and ovarian cancer and whether that will rush them into having families. That’s a long life of being concerned about things you shouldn’t have to worry about at 21. (ID 11, high health anxiety female, no prior cancer)

Well my aunt also has [LS] and she had to go through… a hysterectomy and a fair bit of surgery and pain. I guess with the girls that might be the worst. (ID 12, low health anxiety male, prior colon cancer)

Cancer

Not surprisingly, the most commonly feared LS consequence in both groups was that their children would develop cancer. However, parents were less concerned about the eventuality of children developing colon cancer, and were more focused on cancers difficult to detect and treat, such as ovarian cancer.

Coping strategies

Parents were asked about behaviors or strategies used to manage anxiety about their child's health, which were grouped into: (1) Solution Focused Coping, (2) Emotional Support and Acceptance Based Coping, and (3) Dysfunctional Coping.

Solution focused coping

I just feel like I need to put [my children] on a good path…you know, if we’re eating junk food and we’re going to McDonald’s every week or whatever.. Because they can’t – it doesn’t even matter whether or not they have Lynch - they can’t have that lifestyle. And if they do have Lynch, then they really have to be careful. (ID 4, high health anxiety female, no prior cancer)

Emotional support and acceptance based coping

It’s too bad [that they may have LS], but that’s just the way life is. People, some people have the history of heart disease in their family so it’s passed on from generation to generation. So I don’t know, I don’t think sons blame their fathers for passing on heart disease it’s just the way it is. (ID 12, low health anxiety male, prior colon cancer)

Dysfunctional coping

I try to make connections between what I see in [my child’s] health and mine. … Every new symptom that comes up is like a tick that confirms that she has [LS]. (ID 11, high health anxiety female, no prior cancer)

4 DISCUSSION

The current study contrasted the experiences of parents with LS with high health anxiety to those with low health anxiety. Overall, the experience of LS is stressful, which creates a common experience for the vast majority of parents with LS.

4.1 Health anxiety and current health perceptions

Contrary with expectations, individuals with high health anxiety did not evaluate their health more negatively than those with low health anxiety. People with high health anxiety tend to have a constricted definition of what constitutes good health, believing that physical symptoms reflect that one is “no longer healthy” (Weck, Neng, Richtberg, & Stangier, 2012). However, the primary concerns discussed by all participants, regardless of health anxiety, were fears of developing or experiencing a recurrence of cancer, dying from cancer, and the impact that cancer or death would cause to their family and loved ones. Similar apprehensions have been noted in previous literature on LS (Aktan-Collan et al., 2013; Carlsson & Nilbert, 2007). In examining patients’ worries in greater detail, however, high health anxious individuals spoke more frequently about their worries and described them as more extreme (e.g., dying from cancer as inevitable). Such group differences were expected given the plethora of studies that show a strong relationship between catastrophic thinking patterns and high health anxiety (e.g., Gautreau et al., 2015), as well as a propensity to believe serious illness is likely (Hadjistravropoulos et al., 2012). As our findings indicate, individuals with low health anxiety experience less distress about their health and think pragmatically about the consequences of having cancer or dying. In contrast, those with high health anxiety are acutely aware of their emotional distress related to LS and have difficulty managing emotions.

Relatedly, clear differences emerged between the two groups regarding dysfunctional coping to manage health-related worries. Nearly every high health anxiety participant reported at least one dysfunctional coping strategy (e.g., catastrophizing, avoidance, rumination) while this pattern was absent in the low health anxiety group. These findings mirror those reported among participants who are physically healthy (such as university students without medical problems), which also show a significant relationship between heightened health anxiety and coping using self-blame, blaming others, rumination, and catastrophizing (Görgen, Hiller, & Witthöft, 2014). Dysfunctional coping appears to be unique to those with high health anxiety, which highlights a possible target for future interventions with this population. However, it is also possible that the coping strategy of catastrophizing could be conceptualized as defensive pessimism (Norem & Cantor, 1986), which is the tendency to “expect the worst” as a way to manage anxiety when outcomes are uncertain. This strategy was documented in a study of Asheknazi Jewish participants who were tested for BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants (Kelly et al., 2003), wherein the majority of participants engaged in defensive pessimism. The authors suggested that believing the worst about genetic testing results, despite receiving counseling information to the contrary, may be a way to manage negative affect. Future research should examine the beliefs that participants hold about their specific coping strategies to manage health anxiety, which may further help to tailor interventions.

Despite that the majority of participants had a cancer that preceded the LS diagnosis, cancer history was not mentioned in either group as a factor in perceptions of their own health. Time since participants’ first cancer diagnosis was more than 10 years, and their most recent cancer diagnosis was more than 8 years prior, therefore it is possible that previous cancer did not factor into current health perceptions. Although we cannot definitively say why a history of cancer is not associated with greater health anxiety, the current concerns around screening for new cancers and living with this uncertainty may be more germane to those with high health anxiety. Indeed, high health anxiety participants were more hypervigilant about their health, had more extreme concerns around future cancer, possible death, and the impact of death on their family.

5 THE IMPACT OF HEALTH ANXIETY ON PERCEPTIONS OF CHILDREN'S HEALTH

Parents reported worrying about the impact of LS on their child's psychological health as well as physical health, such as cancer screening, prophylactic procedures, and potential diagnosis of cancer. Similar concerns have been reported in the hereditary cancer literature (e.g., Carlsson & Nilbert, 2007; Duffour et al., 2016), however, our study found that parents’ worries were focused on difficult to detect cancers (e.g., ovarian cancer). Such fears are realistic given that surveillance for gynecological cancers (e.g., ovarian) are far less effective than screening for colorectal cancers (Giardiello et al., 2014).

However, only parents with high health anxiety worried about the negative psychological consequences of an LS diagnosis for their children, and in fact, mirrored fears about their own health. As expected, individuals with high health anxiety were focused on the negative emotional experience of LS and assumed that their children will have a similar experience to their own. Additionally, health anxiety appears to influence coping strategies used to manage worry about their children's health. Low health anxiety parents utilized solution-focused coping, emotional support, and acceptance-based coping most frequently. Importantly, only parents with high health anxiety used dysfunctional coping strategies (e.g., catastrophizing, avoidance) when worrying about their children's health. This pattern is similar to coping with one's own health concerns, with only the high health anxiety group reporting dysfunctional coping. Importantly, this is the first study to show health anxiety is associated with poor parental coping related to their children's current and future health.

6 LIMITATIONS OF THE PRESENT STUDY

An important limitation is that we examined participants with health anxiety at the low and the high end of the spectrum; therefore, the experience of those with mid-range health anxiety was not represented in this study. A second limitation is that we did not measure health anxiety on the SHAI at the time of the interview. Although health anxiety has been shown to be quite stable over time (e.g., Barsky et al., 1998; Fernàndez et al., 2005; Fink et al., 2010), it is possible that participants’ health anxiety had changed from the time they completed the larger study to when they were interviewed. The participant characteristics are another limitation. As noted earlier, the majority of participants had received an LS diagnosis several years earlier and were primarily Caucasian, employed, highly educated, and in a partnered relationship. Parents with high health anxiety tended to have a higher average annual income in addition to having fewer children diagnosed with LS compared to those with low health anxiety. Although this study was not designed to examine parents with adult children (who would be more at risk for LS-related cancers and eligible for screening and for risk-reducing surgeries) compared to parents with younger children, it is possible that health anxiety may be enhanced or ameliorated depending on the characteristics of the offspring's age and health management strategies. Morevover, individuals with different backgrounds and demographics might yield different experiences with health anxiety, as well as, those who were more recently diagnosed with LS or an LS-related cancer. Exploring these differences would be an important avenue of future research. Given that the interviews were completed in 2013, we also acknowledge that the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for genetic testing and assessment of colorectal cancer (Gupta et al., 2017) now recommend that spouses of individuals with LS be advised about the possibility of Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency in their children (CMMRD; caused by inheriting biallelic germline MMR gene pathogenic variants). As most participants in this study had LS genetic counseling many years prior to the revised NCCN guidelines and had no children with CMMRD, it is possible that responses would differ for individuals newly diagnosed with LS.

As a final limitation, the interviewers for the study were also the individuals who coded the transcripts, which introduces additional biases at the time of data collection and coding. We attempted to mitigate against the risk for bias by stating this, consistent with best practices (e.g., Marshall & Rossman, 2016) to allow for any impact of the bias in interpretation to be discernable. As well, we included a team approach to coding, and instituted a number of checks to ensure trustworthiness of our coding. Notwithstanding, it is conceivable that the identity, voice, perspectives, and assumptions of the researchers impacted their interviewing and coding.

7 PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS

Despite these limitations, this study showed that individuals with high health anxiety are quite focused on the negative aspects of LS and employ more dysfunctional coping related to their own and their children's health. Individuals living with LS who have elevated health anxiety may be at risk for worse psychosocial outcomes. Providing support and teaching more effective coping to this group may help improve quality of life but also help to prevent children from experiencing similar distress, as prior research shows similarity between child and parental coping and that parents provide crucial information to their children about how to cope with health stress (e.g., Blount et al, 1989; Hildenbrand, Clawson, Alderfer, & Marsac, 2011).

Clinicians working with LS patients should strive to assist this subset to develop healthier coping. In particular, when giving out positive LS results, genetic counselors may want to pre-emptively discuss strategies with patients for how and when to inform their children about their results. As well, a discussion with patients focusing on the positives of knowing one has LS might be beneficial, such as the effectiveness of regular colonoscopies in preventing colorectal cancer. It might also be useful for genetic counselors to directly inquire how patients are thinking about and coping with their own positive testing results, as well as their children's risk of LS, to answer questions they have thought of since the original results session, and to correct any potential misinformation. For LS patients who report struggling with health anxiety, clinicians may want to consider a referral for cognitive-behavioral therapy for health anxiety, which has been shown to be highly effective for this problem (Hedges’ g = 0.95; Olatunji et al., 2014) and can be conducted in person as well as over the internet (Hedman et al., 2011). When patients do not self-report health anxiety, genetic counselors could attempt to recognize patients that might benefit from a referral for a psychological assessment using a psychosocial screening tool designed specifically for the genetic testing context (Esplen et al., 2013). A combination of these strategies could help lessen health anxiety.

8 CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors (Albiani, McShane, Holter, Semotiuk, Aronson, Cohen, Hart) declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was conducted to fulfill a degree requirement for the PhD for Dr. Jenna Albiani.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Jenna J. Albiani: Dr. Albiani conceived of this project, collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, made significant contributions to drafting the work, provided final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work regarding accuracy and integrity.

Kelly E. McShane: Dr. McShane cosupervised this project from its conception, including data analysis and interpretation, made significant contributions to drafting the work, provided final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work regarding accuracy and integrity.

Spring Holter: Ms. Holter was involved in project design and data interpretation, made significant contributions to drafting and reviewing the work, provided final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work regarding accuracy and integrity.

Kara Semotiuk: Ms. Semotiuk was involved in project design and data interpretation, made significant contributions to drafting and reviewing the work, provided final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work regarding accuracy and integrity.

Melyssa Aronson: Ms. Aronson Ms. Semotiuk was involved in project design, data collection, and data interpretation, made significant contributions to drafting and reviewing the work, provided final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work regarding accuracy and integrity.

Zane Cohen: Dr. Cohen was significantly involved in data interpretation, drafting and reviewing the work, provided final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work regarding accuracy and integrity.

Tae L. Hart. Dr. Hart was the supervisor on this project and was significantly involved in study conception and design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, made significant contributions to drafting and revising the work, provided final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work regarding accuracy and integrity.