RKIP and cellular motility

Dear Dr. Stein,

Raf kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP or PEBP1) is a small and the only physiological inhibitor of Raf-1 protein identified to date. Recent data, however, show that RKIP transcends its inhibitory functions of multiple intracellular and fundamental pathways to act as an activator for others. The article published in the Journal of Cellular Physiology entitled “Possible role of RKIP in cytotrophoblast migration: immunohistochemical and in vitro studies” by Ciarmela et al. shows that RKIP is expressed in the cytotrophoblasts but not in the syncytiotrophoblasts in normal trophoblastic tissues and that this pattern is reversed in pre-eclampsia. Using HTR-8/SVneo, a first trimester cytotrophoblast cell line, the authors also show that inhibition of RKIP by locostatin reduced wound closure (Ciarmela et al., 2011).

The authors utilized a single RKIP inhibitory methodology, namely locostatin to explore the role of RKIP in trophoblast motility in vitro. Locostatin is an oxazolidinone derivative discovered by Fenteany group as an inhibitor of cellular locomotion in a variety of cell types and was shown to bind and inhibit RKIP (Zhu et al., 2005; Mc Henry et al., 2008). Later, in Marsha Rosner Lab, locostatin was shown to inhibit cellular motility independent to its binding to RKIP or activating the RAF-MAPK-ERK signaling pathway (Shemon et al., 2009). In fact, locostatin induced microtubules and cytoskeletal abnormalities in RKIP−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Shemon et al., 2009). A data indicating that locostatin can influence cells in more ways than merely binding or inhibiting RKIP. Consequently, the sole dependence of this published article on locostatin is questionable and the data within may be speculative. It would have been of benefit to the scientific community to have additionally performed the experiments using RKIP silencing technology to corroborate the data.

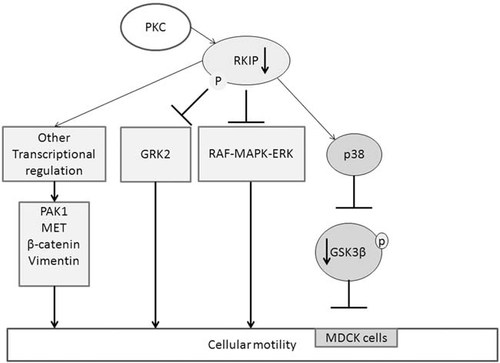

Cellular motility is a complex process that depends on at least three intracellular cascades, namely GRK2-RAC-PAK-MEK-ERK (Penela et al., 2009), the MAPK (Yeung et al., 2000; Yeung et al., 1999), and GSK3β (Al-Mulla et al., 2011a), which are all controlled, in part, by RKIP (Fig. 1). Recently, we have shown that silencing of RKIP in HEK-293 cells induces cellular motility and rapid wound closure in vitro (Al-Mulla et al., 2011b). RKIP silencing appears to influence motility in a cell specific manner. In most cell types, RKIP expression inhibits cellular motility and conversely its silencing enhances it. In MDCK cell, however, the effect of RKIP on cellular motility is reversed. Here, RKIP expression induces cellular motility and visa versa. It is worthy of note that MDCK cells depend on GSK3β for their motility. We have shown that RKIP stabilizes GSK3β and that RKIP silencing induces a rapid p38 activation and phosphorylation of GSK3β at Thr-390 that culminates in its degradation (Al-Mulla et al., 2011a). Therefore, loss of RKIP induces the ubiquitination of GSK3β. In cells like MDCK loss of RKIP and consequently GSK3β, may therefore be key to understand why these cells become less motile compared to other cells. Consequently, the authors of this article may have benefited from studying the expression of GSK3β in their in vivo and in vitro systems. Moreover, their conclusions may have been aided by the inclusion of GRK2 expression data before and after locostatin treatment and the use of western blotting, rather than cytochemistry to study Raf-MAPK-ERK-pathway activation. The authors show that p-ERK is increased after locostatin treatment indicating, as expected, the activation of RAF-MAP-ERK pathway, the abstract unfortunately states the opposite!

Control of cellular motility by RKIP. Loss of RKIP expression induces the activity of the RAF-MAPK-ERK pathway and the transcriptional upregulation of PAK1, MET, β-catenin and vimentin, which are molecules associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Phosphorylation of RKIP by PKC, induces the inhibition of GRK2, a process that is minimized after RKIP depletion, leading to increased activity of GRK2 and enhanced cellular motility. Reduction or loss of RKIP activates p38 by enhancing the redox process, which leads to the inactivation and ubiquitination of GSK3β and loss of cellular motility in cells dependent on GSK3β for cellular motion.

The scientific community may have benefited from measuring GRK2 activity after locostatin treatment and subsequent p-RKIP reduction. This is important, given that GRK2 availability and enhanced activity is associated with positive modulation of cellular motility (Penela et al., 2009).

Overall, I acknowledge that the expertise of the Ciarmela et al. investigators is in the area of placental immunohistochemistry and that the altered RKIP localization during pre-eclampsia may be important and significant and that these observations are not in question. However, it is also evident that the authors “overlooked” some of the recent and relevant RKIP-related literature.