Structure and function of mycobacterium glycopeptidolipids from comparative genomics perspective

Abstract

Glycopeptidolipids (GPLs) attached to the outer surface of the greasy cell envelope, are a class of important glycolipids synthesized by several non-tuberculosis mycobacteria. The deletion or structure change of GPLs confers several phenotypical changes including colony morphology, hydrophobicity, aggregation, sliding motility, and biofilm formation. In addition, GPLs, particular serovar specific GPLs, are important immunomodulators. This review aims to summarize the advance on the structure, function and biosynthesis of mycobacterium GPLs. J. Cell. Biochem. 114: 1705–1713, 2013. © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Mycobacteria can synthesize lipid-rich cell walls which confer these bacteria with many unique features such as proliferation in host macrophage phagolysosome, antibiotics resistance, and biofilm developing. The mycobacteria cell walls include peptidoglycan–arabinogalactan core coated by a lipid bilayer. The interior of the lipid bilayer consists of mycolic acids covalently attached to arabinogalactan, and the free glycolipids and phospholipids form the exterior of the lipid bilayer. The outer layer glycolipids usually confer various mycobacterium distinct surface features. Glycopeptidolipids (GPLs) are relatively important glycolipids produced by non-tuberculosis mycobacteria (NTM), including Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), M. abscessus, M. chelonae, M. smegmatis, M. fortuitum, M. porcinum, M. senegalense, M. xenopi, etc. Due to their important role in mycobacterium physiology and pathogenesis, GPLs have been studied since 1960s. This review will summarize the structure, function, biosynthesis, and regulation of mycobacterium GPLs.

GPLs STRUCTURE

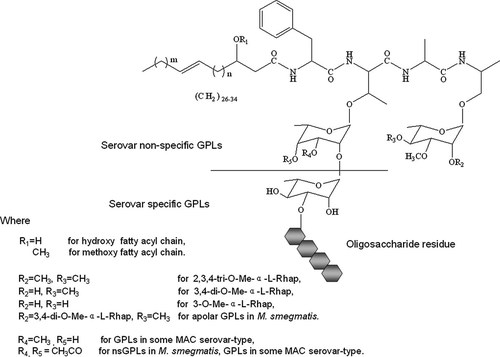

GPLs can be produced by nearly all NTM. These GPLs share a lipopeptide core of C26-34 fatty acids amidated with D-Phe-D-alloThr-D-Ala-L-alaninol. The allo Thr residue of this core is glycosylated with 6-deoxy-α-L-talose (dTal) and the alaninol residue is glycosidically attached to α-L-rhamnose (Rha), while the C3 of the fatty acids is usually hydroxylated or methoxylated as depicted in Figure 1. These diglycosylated GPLs constitute the apolar GPLs or non-serovar specific GPLs (nsGPLs), and further glycosylation of dTal is responsible for the formation of the polar GPLs or serovar specific (ssGPLs) with high immunogenicity. M. smegmatis synthesizes nsGPLs whose dTal is often acetylated and Rha is 3,4-di-O-methylated or 2,3,4-tri-O-methylated [Billman-Jacobe, 2004]. MAC produce both nsGPLs and ssGPLs whose dTal contains 3-O-Me sometimes and the terminal Rha is usually 3-O-methylated or 3,4-di-O-methylated. Different oligosaccharide residues of ssGPLs are chemical basis of various serotypes of MAC. Serovar 1-specific GPL with α-L-Rha-(1 → 2)-α-L-dTal is the simplest among the 31 ssGPLs identified so far [Chatterjee and Khoo, 2001].

The general structure of GPLs in non-tuberculosis mycobacteria. The additional oligosaccharide appendage linked to the 6-deoxytalose differentiates serovar specific (polar) GPLs found in MAC from non-serovar specific (apolar) GPLs. Though they share the lipopeptide core, there are slight differences between nsGPLs of MAC and M. smegmatis in the modification of the Rha and dTal. M. smegmatis sometimes produces the polar GPL with the diglycosylation at the alaninol.

Some mycobacteria species have distinct GPLs. M. xenopi, for example, synthesizes serine-containing GPLs whose peptide core is L-Ser-L-Ser-L-Phe-D-alloThr-COOMe, fatty acyl group is dodecanoyl instead of the C32–C35 acyl in MAC GPLs, and a 3-O-Me-α-L-dTal substituent is linked to the N-terminal serine residue [Chatterjee and Khoo, 2001]. A recent study indicated that there was a substitution of D-valine for the D-phenylalanine of the peptide core in a new GPL produced by MAC [Matsunaga et al., 2012]. A novel family of GPLs, whose lipopeptide core consists of a tripeptidyl amino-alcohol with a di-O-acetyl-6-dTal substituting for the allo Thr and a 2-succinyl-3,4-di-O-Me-Rha attached to the distal alaninol, was found in M. smegmatis [Villeneuve, 2003]. Furthermore M. smegmatis expresses the polar GPL with a hyperglycosylation of the terminal Rha under carbon starvation [Ojha et al., 2002; Mukherjee et al., 2005]. M. fortuitum biovar. Peregrinum also has a kind of special GPL whose oligosaccharide residue is linked to the alaninol unit and a 3-O-Me-α-L-Rha instead of the dTal is attached to the allo Thr [López Marin et al., 1991]. The presence of these new GPLs structures might result from the bacterial survival adaption to their habitats or the stresses.

GPLs BIOSYNTHESIS

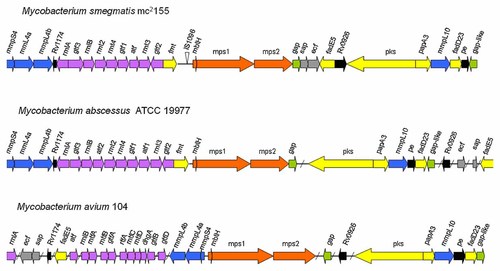

GPLs biosynthesis is a fascinating topic. The genes involved in the biosynthesis of GPLs might be new targets for the drugs against mycobacteria. The traditional method to identify these genes is to screen the interested mutants from transposon insertion mutant libraries. Bioinformatics prediction contributes to exploring GPLs synthetic pathway as diverse mycobacterium genomes were sequenced. Nearly 30 genes organized in clusters and conserved in NTM, participate in GPLs biosynthesis. These genes, many in operons, are responsible for the synthesis of peptide core and fatty acid acyl chain, the modification of GPLs core (glycosylation, methylation, acetylation), the assembly of various synthesizing enzymes on the cell membrane and the export of GPLs, respectively. GPLs locus is around 65 kb in M. smegmatis [Ripoll et al., 2007; Mukherjee and Chatterji, 2012]. M. abscessus and M. chelonae have the GPLs locus similar to that of M. smegmatis, but the genes involved in synthesis of fatty acid chain are comparatively scattered. These genes are distant to those for peptide core synthesis. MAC genomes contain many additional genes coding ssGPLs modification enzymes. It can be hypothesized that the compact architecture of GPLs locus in M. smegmatis represents an ancestral form [Ripoll et al., 2007] evolved to generate diverse GPLs locus found in other NTM genomes as illustrated in Figure 2. There are some homologus proteins of GPLs biosynthases found in M. tuberculosis genome (Table I), but they are more scattered and some have already been reported to be involved in the synthesis of other components, for example, Rv2952 (ortholog of MSMEG_0393) and Rv0101 (ortholog of MSMEG_0402) both participate phthiocerol dimycocerosates (PDIM) synthesis. M. tuberculosis genome has the vestige of GPLs biosynthesis capability. Unlike M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis might adopt different evolution to produce components (like PDIM) instead of GPLs to fit its niche.

Genetic structure of the GPL biosynthesis locus in M. smegmatis, M. abscessus, and MAC serovar 1. Arrows represent the ORFs not drawn to scale. Color code: blue: members of mmpSL family; purple: saccharides biosynthesis, transfer and modifications; red: tripeptidly amino alcohol biosynthesis; green: GPL export to the cell surface; yellow: fatty acyl chain biosynthesis, modification and transfer; grey: possible regulatory genes [Ripoll et al., 2007]; black: unknown.

| M. smegmatis | M. abscessus | M. avium 104 | M. tuberculosis H37Rv | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Gene symbol | Proposed function | Gene symbol | %a | Gene symbol | %a | Gene symbol | %a |

| mmps4 | MSMEG_0380 | Members of the MmpS family. Required for assembly of GPLs synthesis enzymes in cell membrane+ | MAB_4117c | 78 | MAV_3247 | 59 | Rv0451c | 60 |

| mmpL4a | MSMEG_0381 | Members of the MmpL family. Required for assembly of GPLs biosynthases in cell membrane+ | MAB_4116c | 78 | MAV_3248 | 67 | Rv0450c | 64 |

| mmpL4b | MSMEG_0382 | Members of the MmpL family. Required for assembly of GPLs biosynthases in cell membrane+ | MAB_4115c | 76 | MAV_3249 | 65 | Rv0450c | 63 |

| Rv1174 | MSMEG_0383 | None | MAB_4114 | 48 | MAV_3362 | 54 | Rv1174c | 100 |

| rmlA | MSMEG_0384 | Glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase* | MAB_4113 | 85 | MAV_4820 | 80 | Rv0334 | 79 |

| gtf3 | MSMEG_0385 | D-rhamnose rhamnosyltransferase+ | MAB_4112c | 70 | Rv1524 | 57 | ||

| Rv1526c | 52 | |||||||

| rmlB | MSMEG_0386 | dTDP glucose 4,6 dehydrogenase* | MAB_4111c | 78 | MAV_3269 | 76 | Rv0536 | 33 |

| MAB_4110c (atf2) | MAV_3268 (mtfA) | |||||||

| rmt2 | MSMEG_0387 | Rhamnose 2-O-methyltransferase+ | MAB_4109c | 72 | ||||

| rmt4 | MSMEG_0388 | Rhamnose 4-O-methyltransferase+ | MAB_4108c | 83 | MAV_3266 (mtfB) | 78 | ||

| MAV_3261 (mtfC) | 80 | |||||||

| MAV_3262 (rtfA) | ||||||||

| gtf1 | MSMEG_0389 | D-allo-threonine 6-deoxytalosyltransferase+ | MAB_4107c | 76 | MAV_3265 (gtfA) | 75 | Rv1524 | 58 |

| Rv1526c | 51 | |||||||

| atf | MSMEG_0390 | 6-deoxytalose 3,4-O-acetyltransferase+ | MAB_4106c (atf1) | 72 | MAV_3274 | 61 | ||

| rmt3 | MSMEG_0391 | Rhamnose 3-O-methyltransferase+ | MAB_4105c | 82 | MAV_3260 (mtfD) | 82 | ||

| MAV_3259 (dhgA) | ||||||||

| gtf2 | MSMEG_0392 | L-alaninol rhamnosyltransferase+ | MAB_4104 | 67 | MAV_3258 (gtfB) | 65 | Rv1524 | 58 |

| Rv1526c | 52 | |||||||

| MAV_3253 (gtfD) | ||||||||

| fmt | MSMEG_0393 | Fatty acid O-methyltransferase+ | MAB_4103c | 68 | Rv2952 | 56 | ||

| Rv1523 | 54 | |||||||

| mbtH | MSMEG_0399 | None | MAB_4100c | 91 | MAV_3245 | 81 | Rv2377c | 76 |

| mps1 | MSMEG_0400/0401 | Peptide synthase. Synthesis of the dipeptide* | MAB_4099c | 69 | MAV_3244 | 67 | Rv0101 | 44 |

| Rv2379c | 34 | |||||||

| mps2 | MSMEG_0402 | Peptide synthase. Synthesis of the amino acid alcohol* | MAB_4098c | 72 | MAV_3243 | 72 | Rv0101 | 64 |

| Rv2379c | 37 | |||||||

| gap | MSMEG_0403 | Integral membrane protein. Required for GPL export+ | MAB_4097c | 58 | MAV_3059 | 35 | Rv1517 | 32 |

| Rv3821 | 30 | |||||||

| sap | MSMEG_0404 | Sigma associated protein* | MAB_4454c | 31 | MAV_4518 | 42 | ||

| ecf | MSMEG_0405 | Sigma factor of the ECF family* | MAB_4459c | 48 | MAV_4519 | 44 | Rv1189 | 30 |

| fadE5 | MSMEG_0406 | Fatty acid dehydrogenase* | MAB_4437 | 78 | MAV_3309 | 66 | Rv0244c | 81 |

| Rv0926 | MSMEG_0407 | None | MAB_4633 | 36 | MAV_2461 | 39 | Rv0926c | 39 |

| pks | MSMEG_0408 | Fatty acid synthesis+ | MAB_0939 | 79 | MAV_1763 | 76 | Rv3825c | 43 |

| Rv2048c | 41 | |||||||

| papA3 | MSMEG_0409 | Transfer of the fatty acid from Pks to the peptide synthase+ | MAB_0938c | 77 | MAV_1762 | 76 | Rv1182 | 55 |

| mmpL10 | MSMEG_0410 | Members of the MmpL family* | MAB_0937c | 76 | MAV_1761 | 67 | Rv1183 | 57 |

| fadD23 | MSMEG_0411 | acyl-CoA synthase* | MAB_0935c | 73 | MAV_1759 | 71 | Rv1185c | 61 |

| pe | MSMEG_0412 | None | MAB_0936c | 64 | MAV_1760 | 67 | Rv1184c | 45 |

| gap-like | MSMEG_0413 | Integral membrane protein* | MAB_0934 | 55 | MAV_1758 | 57 | Rv3821 | 44 |

| Rv1517 | 30 | |||||||

- +, Experimentally validated function; *, predicted function.

- a Percentage of identity between M. abscessus, M. avium or M. tuberculosis genes and M. smegmatis genes.

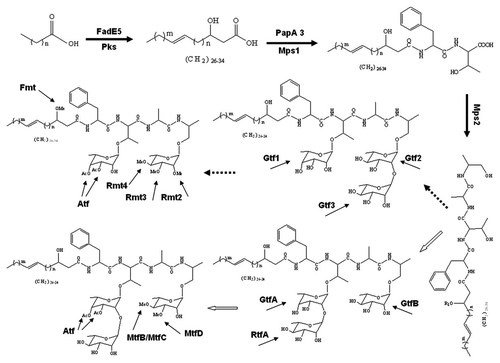

SYNTHESIS OF THE LIPOPEPTIDE CORE

It is believed that an Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (FadE5) incorporates an unsaturation into the fatty acyl chain generated by the fatty acid synthase system in mycobacteria (FAS I and FAS II), then this fatty acyl chain is extended and hydroxylated by the polyketide synthase Pks [Trivedi et al., 2004; Mukherjee and Chatterji, 2012]. The hydroxylated fatty acyl chain transferred from Pks to the peptide synthase (Mps), with the help of the polyketide synthase associated protein (PapA3), is attached to the tripeptidyl amino-alcohol [Trivedi et al., 2004; Mukherjee and Chatterji, 2012; Tatham et al., 2012]. Mps identified by Billman-Jacobe and his colleagues in 1999 from the Tn insertion mutant library of M. smegmatis consists of four function modules responsible for the formation of tripeptidyl amino alcohol skeleton. The first three modules with racemase activity generate the D configuration of the target amino acids and add these D form amino acids to the fatty acyl chain. The module IV without racemase activity incorporates a L-alanine into the tripeptide D-Phe-D-alloThr-D-Ala and further reduces this L-alanine to a L-alaninol [Billman-Jacobe et al., 1999; Mukherjee and Chatterji, 2012]. The above enzymes synergize to form the lipopeptide core. In the following studies, mps was annotated three ORFs, namely mbtH, mps1, mps2 [Sondén et al., 2005], and the last two might be responsible for the synthesis of the dipeptides and the amino alcohol, respectively [Ripoll et al., 2007]. A recent report revealed that mbtH-like gene (MSMEG_0399) played an important role in GPLs biosynthesis though its concrete function remained unknown [Tatham et al., 2012]. mbtH may affect the formation of the lipopeptide core due to its invariably adjacent position to mps1 in many mycobacteria GPLs loci. Being Mps homologous proteins, PstA and PstB in MAC are essential for peptide core formation [Freeman et al., 2006].

GLYCOSYLATION OF GPLs

In M. smegmatis, the glycosyltransferases encoded by gtf1 and gtf2 are responsible for the transfer of dTal and Rha to the allo-threonine and the alaninol respectively, while the production of the polar GPLs depends on Gtf3 which, under carbon starvation, transfers a 3-O-Me-Rha or 3,4-di-O-Me-Rha to the 3,4-di-O-Me-Rha residue linked to L-alaninol. The expression of gtf3 regulated by environmental factors such as the nutrient condition or sigma factor is usually repressed [Miyamoto et al., 2006]. rmlA and rmlB found in the GPLs locus of M. smegmtis encode the putative glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyl transferase and dTDP glucose 4,6 dehydrogenase, respectively. These two enzymes might be involved in the synthesis of some substrates for GPLs biosynthesis like deoxyhexoses, Tal and Rha [Billman-Jacobe, 2004]. In the case of M. avium, GtfA and GtfB share the function of M. smegmatis Gtf1 and Gtf2 [Eckstein et al., 2003]. In 1991, Belisle et al. isolated from M. avium serovar 2 strain TMC 724 the ser2 gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of oligosaccharide residues attached to the dTal [Belisle et al., 1991]. This cluster consists of ser2A-ser2D four functional regions among which ser2A encodes the rhamnosyltransferase, ser2B and ser2D encode methyltransferases required for the methylation of the fucose at C3 and C2, respectively. The fucosyltransferase is encoded by ser2C or ser2D, both are involved in the synthesis of fucose [Mills et al., 1994]. The ser2A locus contains three ORFs, one of which designated rtfA encodes the rhamnosyltransferase required specifically to transfer a Rha to the 6dTal instead of the alaninol [Eckstein et al., 1998; Maslow et al., 2003]. The incorporation of the fucose in serovar 2 GPL is dependent on gtfD, and the adjacent genes mdhtA and merA are responsible for the formation of fucose [Miyamoto et al., 2007]. In MAC serovar 8 strain, gtfTB encodes the glucosyltransferase essential for serovar 8-specific GPL [Miyamoto et al., 2008]. In the serovar 4 strain frequently isolated from HIV AIDs patients, there is a 4-O-Me-Rha via 1 → 4 linkage to the fucose in ssGPL. A rhamnosyltransferase encoded by hlpA transfers this rhamnose residue to the fucose residue of serovar2-specific GPL to form serovar4-specific GPL [Miyamoto et al., 2010]. There were some studies on the glycosylation of other ssGPL such as serovar 7-specific GPL [Fujiwara et al., 2006] and serovar 12-specific GPL [Nakata et al., 2008].

METHYLATION AND ACETYLATION OF GPLs

In the M. smegmatis methyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of GPLs, the 3-O-methyltransferase encoded by rmt3 (formerly designated mtf1) can methylate the terminal rhamnose at C3 position [Patterson et al., 2000], whereas the methylations at C2 and C4 are executed by the products of rmt2 (formerly designated mtf4) and rmt4 (formerly designated mtf3) [Jeevarajah et al., 2004]. Fmt (formerly designated Mtf2) catalyses the conversion of the fatty acid chain from the 3-hydroxyl form to the 3-O-methyl form [Jeevarajah et al., 2002]. In M. avium, the 3-O-methylatransferase (the product of mtfD) and 4-O-methyltransferases (encoded by MtfB and MtfC respectively) can modify the rhamnose linked to the alaninol. MtfA might be involved in the methylation of the distal fucose in ssGPLs [Jeevarajah et al., 2004]. In MAC serotype 12 strain, there are two novel ORFs (orfA and orfB) encoding methyltransferases which catalyze O-methylations at the C4 in the Rha residue next to the distal hexose and at the C3 in the terminal hexose respectively. The O-methylations at these positions can distinguish the serotype 12 GPL from the serotype 7 GPL [Nakata et al., 2008]. The function of OrfB is absent in serotype 13 strain, so the difference between serovar 13 GPL and serovar 12 GPL is the absence of methylation at the terminal hexose [Naka et al., 2011]. M. avium genome lacks fmt, therefore the methylated fatty acid chain is not found in its GPLs [Jeevarajah et al., 2004]. The dTal in M. smegmtis GPLs is usually acetylated, and atf1 encodes the enzyme required for the acetylation at these positions. It was shown that the acetylation of the dTal residue occurred independently of the methylation of the Rha residue in M. smegmatis [Recht and Kolter, 2001]. The presence of Atf1 homolog in M. avium genome implies that M. avium GPL dTal might be acetylated in its native pattern. The proposed biosynthesis pathways of GPLs in M. smegmatis and M. avium 104 stain are illustrated in Figure 3.

The proposed pathway of GPLs biosynthesis. Major steps include (1) fatty acyl chain extension, unsaturation and hydroxylation by Pks and FadE5, (2) tripeptidyl amino-alcohol synthesis by Mps1 and Mps2, (3) glycosylation of allo-threonine and alaninol by various glycosyltransferases, (4) methylation and acetylation of the sugars added to the lipopeptide core by the enzymes for the modification of GPL core. The processes following the lipopeptide core formation occurring in M. smegmatis is shown through the dotted arrows, while the counterparts in MAC is represented through the hollow arrows. (Pks, polyketide synthase; FadE5, fatty acyl desaturase; Mps, mycobacterium peptide synthetase; PapA3, Pks associated protein; Gtf, glycosyltransferase; Rmt, rhamnosyl methyltransferase; Fmt, fatty acyl methyltransferase; Atf, acetyltransferase; Rtf, rhamnosyltransferase).

ASSEMBLY OF GPLs SYNTHASES AND EXPORT OF GPLs

GPLs are biosynthesized in the cytoplasm, while their ultimate location is the outmost layer of the cell wall. Which protein transports GPLs across the cell membrane? The members of the mycobacterium membrane proteins (MmpSL) family including MmpS proteins and MmpL proteins contribute to the transportation of many molecules, but not GPLs. The mycobacterium specific integral membrane protein Gap was reported to be responsible for the export of GPLs. Different from the members of MmpSL family, Gap is a new transport protein for small molecules in mycobacteria [Sondén et al., 2005]. Before the function of Gap was reported, Recht et al. found that tmtpC (designated MmpL4b now) disrupted M. smegmatis failed to produce GPLs. Sequence alignment suggested that TmtpC might be responsible for the export of GPLs to the surface of the cell wall [Recht et al., 2000]. A recent report showed that MmpS4 promoted GPLs synthesis and export by acting as a scaffold with MmpL4 for the assembly of GPLs biosynthases on the membrane [Deshayes et al., 2010]. This might underlie the indirect role of TmtpC in GPLs export. Elucidation the function of ORFs in GPLs locus will give more details for the biosynthesis of GPLs.

ABILITY TO AFFECT MYCOBACTERIUM SURFACE PROPERTIES

The hydrophobic fatty acyl chains and the hydrophilic carbohydrate groups make GPLs amphipathic molecules. The head-tail orientation of GPLs on the cell wall remains unknown. GPLs might be linked to the mycolic acids via fatty acyl chains, thereby exposing the polysaccharides [Chatterjee and Khoo, 2001; Mukherjee and Chatterji, 2012]. It also might be true that the hydrophobic tails (composed of the fatty acids chains) exposed outside boost the hydrophobicity of mycobacteria cell walls [Recht et al., 2000; Recht and Kolter, 2001].

The cell wall located GPL is reasonably able to alter the property of the cell wall and phenotypes such as colony morphology, hydrophobicity of cell wall and aggregation of bacteria. It is well known that members of MAC normally exhibit different colony morphologies including smooth transparent (SmT), rough transparent (RgT), smooth opaque (SmO), rough (Rg) ones [Kansal et al., 1998; Torrelles et al., 2002]. Irreversible spontaneous conversion from a smooth strain to a rough strain can accidentally occur. M. abscessus also has smooth and rough strains, but the conversion between these two different strains is reversible [Howard et al., 2006]. It is generally thought that the conversion from the smooth strain to the rough stain results from the deletion or structural change of GPLs. M. smegmatis displays Rg strain due to the mutation of genes involved in GPLs biosynthesis like mps, gtf3, or atf1 [Recht and Kolter, 2001; Deshayes et al., 2005]. In M. avium, the deletion of ser2 genes cluster or gtfA results in the absence of GPL and appearance of Rg strain [Belisle et al., 1993; Eckstein et al., 2003]. M. abscessus Rg strain is devoid of GPLs as well [Byrd and Lyons, 1999]. The GPLs-deficient strain usually exhibits the increase of the cell hydrophobicity and the cellular aggregation [Etienne et al., 2002], which supports the head-tail orientation of GPLs referred in some literatures [Chatterjee and Khoo, 2001; Mukherjee and Chatterji, 2012]. Interestingly gtf3 overexpressed M. smegmatis displays Rg colony morphology identical to that done by GPL-deficient strain, and the cell hydrophobicity and aggregation of this strain also increase [Deshayes et al., 2005].

SUSCEPTIBILITY TO ANTIBIOTICS AND MYCOBACTERIUM PHAGES

GPLs might play a role in the resistance to antibiotics. In M. smegmatis, the absence of GPLs increases the uptake of chenodeoxycholate by the cell wall, indicating GPLs may work as a permeability barrier [Etienne et al., 2002], but the mutant increases moderately the sensitivity only to cephalosporins among many kinds of antibiotics like isoniazid, streptomycin, erythromycin, rifampicin, ethambutol, quinolones, when GPLs of this strain decreases significantly due to the deletion of mbtH-like gene gplH [Tatham et al., 2012]. We also found that GPL-deficient strain had the same susceptibility to rifampicin, streptomycin, isoniazid, and capreomycin as the parent strain. GPLs maybe do not play an expectantly essential role in the integration of permeability barrier of the mycobacteria cell walls.

There are some relationship between GPL and mycobacteriophage. It was reported that nsGPL was the receptor of mycobacteriophage D4 and I3, and the methylated Rha in GPLs was the active sit, while the mutant absent of GPLs remained sensitive to D29 and Bxz1 [Dhariwal et al., 1986; Chen et al., 2009]. The GPL-deficient mutant of M. smegmatis was sensitive to mycobacteriophage D29 and TM4, indicating GPL is the selective receptor for the particular mycobacteriophage.

IMPACT ON SLIDING MOTILITY AND BIOFILM FORMATION

Mycobacteria surface motility exemplified by the transparent halo can be an indication of the feature of their cell wall [Recht et al., 2000]. Both fast-growing saprophytic M. smegmatis and slow-growing conditions pathogenic M. avium can slide [Martínez et al., 1999; Carter, 2003]. In the natural environment, mycobacteria can effectively colonize and spread by sliding motility or biofilm formation. In the water distribution systems, M. avium in the biofilms represents a source of infection of NTM [Freeman et al., 2006]. In animals, the formation of biofilms or sliding favors the epithelial cell invasion and drug-tolerance of mycobacteria [Ojha et al., 2008].

NTM GPLs are believed to contribute to biofilm formation or sliding motility. In M. smegmatis, the formation of biofilm is affected significantly by the deletion [Recht et al., 2000] or change [Recht and Kolter, 2001] of GPLs. This is true for M. avium [Martínez et al., 1999] and M. abscessus [Howard et al., 2006] as well, but the core GPL is dispensable for M. avium biofilm formation, at least on the Permanox and silanized glass surface [Freeman et al., 2006]. The precise mechanism of the effect of GPLs on mycobacterium biofilms formation or sliding motility remains unknown. The electrostatic interaction between the fatty acyl tails of GPLs and the hydrophilic agar surfaces represents one explanation [Recht et al., 2000; Recht and Kolter, 2001]. Currently, no experimental data supporting this interpretation can be found.

ROLE IN THE MYCOBACTERIUM PATHOGENESIS

The location and immunogenecity of M. avium GPLs imply that they might play a role in the pathogenesis. The macrophages infected with GPL-deficient M. avium 2151 strain produces more cytokines and inflammatory chemokines like tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-12p40 (IL-12p40), and RANTES [Bhatnagar and Schorey, 2006]. It was found that ssGPLs as one of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) agonists could promote macrophages activation in myeloid differentiation primary-response protein88 (MyD88)-dependent manner, which stimulated MAPKs p38, Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and NF-κB to facilitate cytokines secretion [Sweet, 2006]. ssGPLs differs in their ability to activate host immune systems with serotype 1 and 2 stimulating the activation of MAPK and NF-κB as well as the release of TNF-α in MyD88 and TLR2-dependent manner, while serotype 4 fails to function in the same manner [Sweet, 2006]. It was also reported in the early study that serovar 8-specific GPLs but not serovar 4 and serovar 20 had the capability to induce secretion of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBM) [Barrow et al., 1995]. In macrophage infections, GPLs can interact with the host membranes and promote mycobacterium survival in the host cells by interfering with membrane-mediated functions [Bhatnagar and Schorey, 2007]. Acetylation plays a key role in the recognition for GPLs by the host immune systems. Only when C4 of 6dTal is acetylated, the serovar 2-specific GPL can induce MyD88- and TLR2-dependent signaling response [Sweet et al., 2008]. The acetylation occurring in the serovar 13-specific GPL is also required for its cognition by TLR2 [Naka et al., 2011]. It is generally believed that nsGPLs cannot stimulate the immune response of the hosts, however it was reported that IgG responses to nsGPLs with acetylated dTal indeed occurred in the guinea pigs with MAC infection. In addition, the pool of anti-ssGPL antibodies was different from that of anti-nsGPL antibodies due to the different recognition fragments (oligosaccharide and acetylation respectively) [Matsunaga et al., 2008]. The acetylation at C4 of dTal and the methylation at C3 of Rha are indispensable for nsGPLs to activate macrophages in MyD88- and TLR2-dependent manner [Sweet et al., 2008]. nsGPLs as well as the mannosylated arabinan can delay phagosome maturation, which depends on the expression of the mannose receptor (MR) [Sweet et al., 2010]. The surface-exposed nsGPLs of M. smegmatis can inhibit the phagocytosis of many mycobacteria including M. smegmatis, M. kansasii, M. avium, and M. tuberculosis, by human macrophages [Villeneuve, 2003]. The internalization of GPL-deficient M. smegmatis by macrophages is also more rapid than that of the parent strain [Etienne et al., 2002].

The impact of GPLs on the virulence is often reflected indirectly by the virulences of the strains with different colony morphologies. In MAC, the relation between the virulence and the colony morphology is complex. M. avium Rg strain is more virulent than SmT and SmO variants in chickens and mice [Schaefer et al., 1970]. Compared with SmT strain, M. avium 101 RgT variant leads to 6–8 times fatality rate in the mice-infection model [Kansal et al., 1998]. It seems plausible that GPL-deficient Rg strain is more virulent than GPL-expressing SmT strain, but there were some contradictory reports, for example, M. avium 104 Rg strain with the lower virulence in mice significantly induced high level of TNF-α production [Krzywinska et al., 2005]. In M. abscessus, the reports about the relation between the colony morphology and the virulence are consistent. It was observed that M. abscessus Rg strain could persist and propagate in the lungs of the infected murine while the smooth variant was cleared soon [Byrd and Lyons, 1999]. Catherinot also found that the GPL-deficient Rg strain led to the higher death rate in the infected mice by intravenous injection [Catherinot et al., 2007]. The absence of GPLs because of the disruption of mmpL4b facilitates the M. abscessus mutant to replicate in the macrophages and activate TLR2 [Nessar et al., 2011]. Clinical data and epidemiological data also showed that the M. abscessus Rg strain was more virulent [Sanguinetti et al., 2001; Jonsson et al., 2007; Catherinot et al., 2009].

The variation among the studies may result from the differences in the strains used and the underlying causes of the morphological changes [Schorey and Sweet, 2008]. For example, the mechanism of conversion between the M. avium strains with colony morphologies is different from that of M. abscessus strains. In M. avium, the irreversible conversion from the smooth strain to the rough variant is due to the deletion of some genes involved in GPL biosynthesis, while the conversion between M. abscessus different strains is bidirectional, indicating they adopt a reversible mechanism rather than lost in GPL synthesis genes. In fact, M. abscessus Rg strain can produce few GPLs instead of the complete deficiency of GPLs [Howard et al., 2006]. The virulence of M. abscessus is not directly reflected with GPLs for it only expresses nsGPLs without strong immunogenicity. These surface-exposed GPLs will mask underlying cell wall lipids involved in stimulating the host immune responses. When GPLs lose or reduce, the underlying bioactive lipids are exposed to interact with the host immune systems, for example, the underlying mannose-containing lipids can activate TLR2 to promote IL-8 and HβD2 expression [Rhoades et al., 2009; Fessler et al., 2011; Nessar et al., 2011; Roux et al., 2011].

Some facets of the GPLs have been established, such as the structure, biosynthesis, and function. However, many outstanding questions remain, such as the regulation of the GPLs biosynthesis, the mechanisms underlying the effect of GPLs on the sliding motility and biofilm formation, the roles of GPLs in the permeability barrier of mycobacteria cell walls and in the interaction between mycobacteria and the hosts. Given the important contributions of GPLs to the physiology and pathogenesis of mycobacteria, the genes participating in the GPLs biosynthesis or/and the regulation might be potential drug target candidates for the drugs against mycobacterium infection, particularly the NTM-caused infection in the immuno-compromised or aged population.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 81071316 and 81271882), National Megaprojects for Key Infectious Diseases (no. 2008ZX10003-006 and 2012ZX10003-003), New Century Excellent Talents in Universities (NCET-11-0703), Excellent PhD Thesis Fellowship of Southwest University (grant nos. kb2009010 and ky2011003), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. XDJK2012D011, XDJK2012D007, XDJK2013D003, and XDJK2011C020), Natural Science Foundation Project of CQ CSTC (grant no. CSTC, 2010BB5002).