Daily association between parent−adolescent relationship and life satisfaction: The moderating role of emotion dysregulation

Abstract

Introduction

In adolescence, life satisfaction is an early indicator of later psychological well-being. However, researchers know little about how daily family relationships shape adolescent life satisfaction. The current study examined the day-to-day associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction, and whether adolescent emotion dysregulation moderated these associations.

Methods

A total of 191 adolescents (Mage = 12.93, SDage = 0.75, 53% female) recruited from junior high schools in Taiwan participated in a 10-day daily diary protocol. We conducted multilevel analyses to examine within-family and between-family processes.

Results

At the within-family level, adolescents reported higher life satisfaction on days when parent–adolescent closeness was higher, but lower life satisfaction on days when parent–adolescent conflict was higher. At the between-family level, higher parent–adolescent closeness was associated with greater life satisfaction on average, while parent–adolescent conflict was not related to adolescent life satisfaction. Cross-level interactions indicated that within-family changes in parent–adolescent closeness and conflict were only associated with life satisfaction for adolescents with higher levels of emotion dysregulation, indicating emotion dysregulation may intensify the role of daily parent–adolescent relationships in shaping adolescent life satisfaction.

Conclusions

This study expands current literature and provides novel evidence that changes in day-to-day parent–adolescent relationships have important implications for adolescent life satisfaction, especially for youth higher in emotion dysregulation. The findings underscore the importance of evaluating family and individual characteristics to better support adolescent well-being.

1 INTRODUCTION

During adolescence, life satisfaction is an important indicator of developmental outcomes such as happiness, well-being, and psychopathology (Haranin et al., 2007; Huebner, 2004; Proctor et al., 2009). Satisfaction with life is also a key construct in the science of positive psychology, which emphasizes the presence of positive outcomes and optimal individual functioning rather than traditional focus on the prevention of mental health problems and psychological disorders (Shogren et al., 2006; Suldo et al., 2014). Adolescence is a sensitive period of development, during which adolescents are more vulnerable to changes in family relationships as well as their own emotional disturbances (Squeglia & Cservenka, 2017; Timmons & Margolin, 2015; Yap et al., 2007). Based on cross-sectional and longitudinal data, past studies have found that the quality of parent−adolescent relationships is consistently associated with adolescent life satisfaction (Jiménez-Iglesias et al., 2017; Schwarz et al., 2012; Shek, 1998). For instance, conflict frequency between parents and adolescents was associated with lower levels of life satisfaction (Zhao et al., 2015). However, relatively little research has investigated the potential day-to-day changes in adolescent life satisfaction and how parent−adolescent relationships may shape these fluctuations. A growing body of research points out that both family relationships and adolescent well-being may shift on a daily basis (e.g., positive and negative mood; eudaimonia) (Fosco et al., 2021; Van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). To address these gaps in literature, the current study sought to examine how daily parent−adolescent relationship (i.e., closeness, conflict) is related to ups and downs in life satisfaction across days. Together, this study aimed to investigate and compare the associations between parent−adolescent relationship quality at both within-family and between-family levels, to contribute to our understanding of family relationships in relation to adolescent life satisfaction.

1.1 Parent−adolescent relationship and life satisfaction

In adolescence, parent–adolescent relationships are important for shaping adolescent well-being and development. Research shows a link between a close, warm, and connected relationship between parents and adolescents and adolescents' positive developmental outcomes, including higher self-esteem, life satisfaction, and psychological functioning (Barber et al., 2003; Gilman & Huebner, 2006; Oberle et al., 2011; Yucel & Yuan, 2016). Parent–adolescent closeness generally refers to the intimacy and connectedness in the relationship between parents and adolescents. For example, previous studies have shown that feeling close to parents was associated with lower depressive symptoms in adolescence (Mak et al., 2021). Lower parent–adolescent connectedness and warmth were associated with higher rates of unhealthy weight control behaviors, suicidal attempts, low self-esteem, and depression (Ackard et al., 2006; Chiang et al., 2022). For instance, studies showed a relationship between perceived higher admiration from parents and higher life satisfaction among adolescent samples across 11 cultures (e.g., the United States, Germany, and China) (Schwarz et al., 2012). In contrast, parent–adolescent conflict is a possible determinant of poor mental well-being and quality of life. Although conflicts between parents and adolescents are normative and sometimes constructive for adolescent development (Laursen et al., 2017), studies have found that high levels of parent–adolescent conflicts are consistently associated with negative outcomes, such as psychological and behavioral problems, adjustment difficulties, and suicidality (Feeney, 2006; Kuhlberg et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2006; Weymouth et al., 2016). As such, researchers found higher conflict frequency and intensity linked to adolescents' lower life satisfaction (Shek, 1998; Zhao et al., 2015).

To date, however, few studies have examined the within-family associations between parent–adolescent relationships and adolescent life satisfaction in day-to-day processes. Past studies regarding life satisfaction did not disentangle between-family differences from within-family changes. These findings have several limitations. First, between-family associations are limited to interfamilial effects and mask the within-family processes. Second, adolescent life satisfaction may not be static; life satisfaction may vary daily. Prior studies using daily diary methods support that adolescent well-being changes over time (i.e., day-to-day fluctuations), including their family relationships (Fuligni & Hardway, 2006; Silva et al., 2020). Last, repeated assessments would provide more robust measures for evaluating adolescents' family relationships and well-being. Together, this study utilized daily diary methods to understand within-family changes in parent–adolescent relationships and how they are related to adolescent life satisfaction.

1.2 Studying life satisfaction in daily life

The daily diary method is useful for assessing the day-to-day fluctuations in adolescents' life and their associated factors. The daily diary method provides more reliable and accurate data than the retrospective assessments common in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Bolger et al., 2003). One advantage of daily diary data is that it can distinguish within-family associations between one family's interpersonal relationships, behaviors, and feelings from between-family characteristics. For instance, on days when adolescents have conflicts with their parents, do they report lower life satisfaction? In contrast, do adolescents experience higher life satisfaction on days when they feel emotionally closer to their parents? As such, the daily diary method allows researchers to disentangle within-family effects from between-family differences, providing valuable information on how changes in day-to-day parent–adolescent relationships are associated with adolescent well-being.

Past research has utilized daily diary methods to examine the links between everyday family relationships and adolescent psychological and emotional responses (Chiang et al., 2023; Mercado et al., 2019; Timmons & Margolin, 2015). For example, adolescents reported more sadness and anger on days when the mother–adolescent conflict was higher than on other days (Mastrotheodoros et al., 2020). Conversely, on days when adolescents perceived more warmth and less conflict than usual, they felt more loved by their parents (Coffey et al., 2022). Additionally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, parents who experienced job loss reported greater parent–adolescent conflicts, which predicted increases in negative affect and decreases in positive affect among adolescents (Wang et al., 2021). These findings suggest that adolescents may experience day-to-day fluctuations in emotions and well-being related to within-family changes in parent–adolescent relationships. However, most existing studies on life satisfaction or quality of life are limited to either cross-sectional or longitudinal panel data that only assessed between-family associations (e.g., Jiménez-Iglesias et al., 2017; Schwarz et al., 2012; Yucel & Yuan, 2016). Thus, our study using daily diary methods may extend the literature by investigating the daily associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction, and assessing whether these associations differ based on individual characteristics.

1.3 Emotion dysregulation as a moderator

Adolescents' emotion dysregulation may moderate the association between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction. Emotion dysregulation refers to the maladaptive emotional responsiveness characterized by dysfunctional emotion regulation and difficulties in managing emotions (Carpenter & Trull, 2013; Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Mennin et al., 2007). The current study drew upon Gratz and Roemer's (2004) definition of emotion dysregulation as a theoretical framework, since past research has widely used it in studies with adolescents, including (a) nonacceptance of emotional responses (denial of distress or not accepting one's emotions), (b) difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior (problems with completing tasks while experiencing negative emotions), (c) impulse control difficulties (difficulties in controlling impulse behaviors as desired), (d) lack of emotional awareness (inattentive to one's emotions), (e) limited access to emotion regulation (perceived beliefs of ineffective emotion regulation strategies, and (f) lack of emotional clarity (unclear about what emotions the individual is experiencing). Emotion dysregulation is a transdiagnostic risk factor associated with adolescents' psychopathology. Over the past decade, an increasing number of studies have reported findings linking emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychological and behavioral problems, including anxiety symptoms, eating pathology, and aggressive behaviors (Herts et al., 2012; McLaughlin et al., 2011; Paulus et al., 2016; Vogel et al., 2021). Systematic reviews also indicate a positive link between emotion dysregulation and suicidal ideation and attempts, as well as schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Liu et al., 2020; Turton et al., 2021).

Although past research has identified a strong relationship between emotion dysregulation and developmental outcomes in adolescence, no study to date has examined the moderating role of emotion dysregulation in the association between parent–adolescent relationships and adolescent life satisfaction. Drawing on the differential susceptibility hypothesis (Belsky, 2005; Ellis & Boyce, 2011), we conceptualized emotion dysregulation as a susceptibility marker that may position emotionally dysregulated adolescents to be more sensitive to both positive and negative environmental influences, compared to less dysregulated adolescents. The differential susceptibility hypothesis suggests that individuals characterized by heightened susceptibility benefit more from supportive environments, but are also more negatively influenced by adverse environments, indicating a for-better-or-for-worse pattern (Belsky et al., 2007; Hartman & Belsky, 2016). Past research has shown that children higher in negative emotionality or difficult temperament exhibited more behavioral problems when faced with lower-quality rearing environments (e.g., poor parenting) and fewer behavioral problems when they were in higher-quality contexts (Belsky, 2005; Pluess & Belsky, 2009). Thus, negative characteristics such as difficult temperament and negative emotionality are not only risk factors related to maladjustment but also can predispose children to benefit from supportive environments (Belsky & Pluess, 2013).

Consistent with the notion of differential susceptibility, we hypothesized that adolescents with high emotion dysregulation might be more sensitive to both positive and negative aspects of parent–adolescent relationships because of their difficulties in effectively and properly regulating emotional distress. When adolescents are more emotionally dysregulated, parent–adolescent relationships may have greater impacts, compared to when adolescents have better emotion regulation skills and can adaptively regulate their emotions. For instance, adolescents higher in emotion dysregulation might be more likely to experience lower life satisfaction on days when parent–adolescent conflict is higher than usual, due to negative emotional arousal and responses to conflicts. In contrast, adolescents lower in emotion dysregulation might be more self-directed and less affected by changes in parent–adolescent relationships. Taken together, the association between life satisfaction and adolescents' experiences of closeness and conflict in their relationships with parents is likely to differ based on the levels of emotion dysregulation.

1.4 The current study

The current study examined the daily associations between parent–adolescent relationships (e.g., closeness, conflict) and life satisfaction in a daily diary sample of Taiwanese adolescents. First, although no study to our knowledge has examined the within-family process of life satisfaction, we hypothesized that adolescents might report higher life satisfaction on days when parent–adolescent closeness was higher than usual, based on previous findings on between-family associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction. In contrast, adolescents might report lower life satisfaction on days when parent–adolescent conflict was higher than usual. Therefore, we simultaneously explored the between-family associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction, to evaluate and control for the between-family differences in the effect of parent–adolescent closeness and conflict. Next, we investigated the role of adolescents' emotion dysregulation in moderating the associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction at the within-family and between-family levels. We hypothesized that, for adolescents with higher emotion dysregulation, same-day parent–adolescent closeness would be associated with greater life satisfaction, while parent–adolescent conflict would be related to lower life satisfaction. In addition, we also explored whether between-family associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction varied based on adolescents' emotion dysregulation. However, the between-family patterns might be different from the within-family processes.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants and procedure

The participants were 191 adolescents (Mage = 12.93, SDage = 0.75, 53% female) recruited from northern cities in Taiwan. All adolescents identified as Taiwanese, and most of their parents (95%) were Taiwanese. We recruited participants through schools, where the research team introduced the study purpose and procedures with the approval of school principals. We required families with adolescents to participate in the baseline and daily diary studies and meet the following eligibility criteria: participating parents were the primary caregivers, they had access to the Internet and daily surveys, and the parents and adolescents had to live together most of the time. Participating adolescents came from families where parent education ranged from below high school (3.7%), high school (20.2%), college degree (60.7%), and graduate degree (15.3%). We conducted data collection online for privacy protection.

We collected diary surveys from Monday to Friday (i.e., school days) for 2 consecutive weeks. We sent all surveys with person-specific links to participants' preferred communication platforms (e.g., emails, phone apps) with secured individualized passwords. Adolescents completed daily surveys twice each day after school and in the evening (i.e., before bed). We only included evening dailies for parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction in the current study, since these two measures were only assessed in the evening. Adolescents completed informed assent, and parents completed informed consent, followed by baseline questionnaires relating to demographics, family relationships, and well-being. We compensated adolescents with cash or gift cards up to $35 after the completion of the study. The compliance rates were high (98.83%) in daily diary data based on the total study days each adolescent could report, and there were no missing data in baseline assessments. The Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved all procedures.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Daily parent−adolescent relationship

Adolescents completed two items concerning parent–adolescent closeness and two on parent–adolescent conflict. Items for closeness included: “I feel close to my parent today” and “I feel supported and loved by my parent today.” Items for conflict included: “My parent and I argued with each other today” and “I had conflicts with my parent today.” Respondents rated items on a slider from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very much) with one increment and averaged to create a single score for parent–adolescent closeness and conflict. Higher scores reflected higher levels of parent–adolescent closeness and conflict. We calculated the within-family (RC) and between-family (R1F) reliability scores to evaluate the scale reliability (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013; Cranford et al., 2006). Daily parent–adolescent closeness (Rc = 0.79; R1F = 0.85) and conflict (Rc = 0.74; R1F = 0.82) had meaningful within-family and between-family changes.

2.2.2 Daily life satisfaction

Adolescents reported their daily life satisfaction each evening with five items: “I was satisfied with my life today,” “I felt good about myself today,” “I was satisfied with my day in school today,” “I was satisfied with my health today,” and “I was satisfied with my relationships today.” They rated the items on a slider from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very much/very satisfied) with one increment and averaged to create a life satisfaction score. Higher scores reflected higher levels of quality of life. Daily life satisfaction demonstrated meaningful within-family and between-family changes (RC = 0.80; R1F = 0.89).

2.2.3 Baseline emotion dysregulation

Adolescents' emotion dysregulation was assessed at baseline using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Short Form (DERS-SF) (Kaufman et al., 2016), a reliable and valid 18-item measure to assess adolescents' difficulties in emotion regulation (e.g., nonacceptance of emotional responses, lack of emotional awareness). Sample items included “When I'm upset, it takes me a long time to feel better” and “When I'm upset, I lose control over my behavior.” Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Items were averaged to create a single score of emotion dysregulation with higher scores indicating higher levels of emotion dysregulation. The Cronbach's ⍺ was .89 in this study.

2.3 Data analysis

Multilevel modeling was used to account for the nested structure of the daily diary data, in which daily reports are nested within adolescents. Data analyses were conducted in R Version 4.2.1. Following the recommendations for exploring within-family and between-family effects in daily diary methods (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013), we used person mean centering and grand mean centering to decompose daily ratings of parent−adolescent closeness and conflict into day-level and person-level predictors. At the day level, person-mean centered scores reflected the deviations within an individual, showing higher or lower than usual levels for an adolescent. At the family level, family-centered means were grand mean centered to reflect the between-family levels in the entire sample over daily diaries. In addition, emotion dysregulation was also grand mean centered to reflect individual levels of emotion dysregulation among adolescents. Models were estimated using the maximum likelihood with the AR (1) error parameter to account for potential autocorrelated errors in the analyses.

A series of model-building processes was conducted to examine the main effects of parent−adolescent closeness and conflict on daily life satisfaction, as well as the moderating role of emotion dysregulation in these effects. First, we examined the effects of both day-level and person-levels of parent−adolescent closeness or conflict, while also controlling for adolescent gender, time, and prior-day life satisfaction. Next, we investigated the moderating role of emotion dysregulation in the within-family association between daily parent−adolescent closeness or conflict and adolescent life satisfaction. Last, we also examined the moderating role of emotion dysregulation in the between-family association between average parent−adolescent closeness or conflict and adolescent life satisfaction.

3 RESULTS

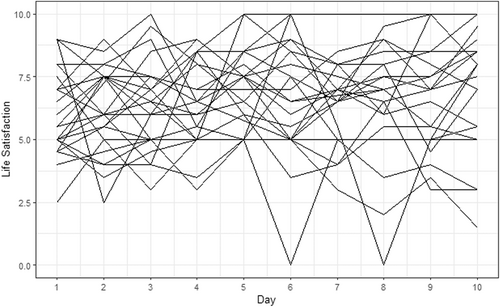

Descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables are presented in Table 1. At both within-family and between-family levels, parent−adolescent closeness was positively correlated with life satisfaction, whereas parent−adolescent conflict was negatively correlated with life satisfaction. In addition, emotion dysregulation was also negatively correlated with life satisfaction at both levels. The Intraclass correlation coefficients were .76, .56, and .69 for parent−adolescent closeness, parent−adolescent conflict, and life satisfaction, respectively. These results showed that a large amount of variability existed on the day level (within-family), compared to the between-family level. To illustrate the variability in daily life satisfaction, a plot of day-to-day life satisfaction is presented in Figure 1.

| Within-family correlations | Between-family correlations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 1. | 2. | 3. | |

| 1. Parent−adolescent closeness | 7.41 | 2.74 | ||||||

| 2. Parent−adolescent conflict | 1.07 | 2.06 | −.29*** | −.19*** | ||||

| 3. Life satisfaction | 7.27 | 2.45 | .52*** | −.25*** | .53*** | −.36*** | ||

| 4. Emotion dysregulation | 2.78 | 0.62 | -.25*** | .14*** | −.25*** | -.28*** | .18*** | −.30*** |

- *** p < .001.

Results of multilevel models were shown in Table 2. The variance explained (R2) in multilevel models was 0.11 for parent−adolescent closeness and 0.10 for the parent−adolescent conflict main effect models. The first model examined the main effects and the following models tested two-way interactions. On days when parent−adolescent closeness was higher than usual, adolescents reported higher life satisfaction (b = 0.16, p < .001), over and above the prior day's life satisfaction. At the between-family level, adolescents higher in parent−adolescent closeness reported higher life satisfaction (b = 0.50, p < .001) on average. However, adolescents higher in emotion dysregulation reported lower life satisfaction (b = −0.51, p = .03), on average. The interaction between daily parent−adolescent closeness and emotion dysregulation was significant; thus, we conducted a simple slope analysis at high (+1SD) and low (−1SD) levels of emotion dysregulation. The results showed that adolescents higher in emotion dysregulation reported greater life satisfaction on days when parent−adolescent closeness was higher (b = −0.22, p < .001). In contrast, parent−adolescent closeness was not associated with life satisfaction for adolescents lower in emotion dysregulation (b = 0.05, p = .19).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-family level | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE |

| Intercept | 7.25*** | 0.17 | 7.25*** | 0.17 | 7.20*** | 0.18 |

| Daily parent−adolescent closeness | 0.16*** | 0.02 | 0.14*** | 0.03 | 0.16*** | 0.03 |

| Prior day life satisfaction | 0.07** | 0.03 | 0.07** | 0.03 | 0.07** | 0.03 |

| Between-family level | ||||||

| Average parent−adolescent closeness | 0.50*** | 0.05 | 0.50*** | 0.05 | 0.51*** | 0.05 |

| Emotion dysregulation | −0.51* | 0.20 | −0.51* | 0.20 | −0.47* | 0.20 |

| Interactions | ||||||

| Daily closeness × emotion dysregulation | 0.13*** | 0.04 | ||||

| Average closeness × emotion dysregulation | −0.11 | 0.09 | ||||

- Note: Adolescent gender and study day were entered as covariates.

- * p < .05

- ** p < .01

- *** p < .001.

Results from models testing parent-adolescent conflict were reported in Table 3. On days when parent−adolescent conflict was higher than usual, adolescents reported lower life satisfaction (b = −0.13, p < .001), over and above the prior day's life satisfaction. At the between-family level, average parent−adolescent conflict was not associated with life satisfaction (b = −0.19, p = .18). Simple slope analysis was conducted to examine the significant moderation of emotion dysregulation in the association between daily and average parent-adolescent conflict and life satisfaction. The results indicated that daily parent−adolescent conflict was not associated with life satisfaction for adolescents lower in emotion dysregulation (b = −0.15, p = .21). In contrast, daily parent−adolescent conflict was negatively associated with life satisfaction for adolescents higher in emotion dysregulation (b = −0.27, p = .005).

| Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-family level | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE |

| Intercept | 7.35*** | 0.21 | 7.35*** | 0.21 | 7.20*** | 0.22 |

| Daily parent−adolescent conflict | −0.13*** | 0.02 | −0.12*** | 0.02 | −0.13*** | 0.02 |

| Prior day life satisfaction | 0.08** | 0.03 | 0.08** | 0.03 | 0.07** | 0.03 |

| Between-family level | ||||||

| Average parent−adolescent conflict | −0.19 | 0.17 | −0.20 | 0.17 | −0.22 | 0.19 |

| Emotion dysregulation | −0.82** | 0.25 | −0.82** | 0.25 | −0.70** | 0.25 |

| Interactions | ||||||

| Daily conflict × emotion dysregulation | −0.10* | 0.04 | ||||

| Average conflict × emotion dysregulation | 0.08 | 0.26 | ||||

- Note: Adolescent gender and study day were entered as covariates.

- * p < .05,

- ** p < .01,

- *** p < .001.

Alternative analyses were conducted to explore whether the associations between parent−adolescent relationship and life satisfaction varied across adolescent gender and age, parent gender, and family income. Only one interaction was significant between daily parent−adolescent conflict and family income; on days when parent−adolescent conflict was higher than usual, adolescents from low-income families reported lower life satisfaction, while this association was not significant for adolescents from high-income families.

4 DISCUSSION

This study examined the within-family associations between parent–adolescent relationships and adolescent life satisfaction in a daily diary sample of Taiwanese adolescents. Specifically, we investigated the relationship between daily changes in parent–adolescent closeness, conflict, and daily fluctuations in life satisfaction, and the moderating role of emotion dysregulation. The results showed that adolescents reported higher life satisfaction on days when parent–adolescent closeness was higher than usual, but lower life satisfaction on days when parent–adolescent conflict was higher than usual. We found these daily associations while accounting for the previous day's life satisfaction (i.e., preventing the carryover effects). Moreover, emotion dysregulation moderated the daily associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction. Adolescents higher in emotion dysregulation reported higher life satisfaction on days when closeness was higher than usual, but lower life satisfaction on days when the conflict was higher than usual. Together, the current study fills the gaps in the existing literature by utilizing daily diary methods to examine associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction at within- and between-family levels.

The findings contribute to the growing body of literature on links between parent–adolescent relationships and adolescent life satisfaction. The associations between higher parent–adolescent closeness and adolescents' greater life satisfaction at within- and between-family levels supports our hypotheses. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with and extend prior research (Fosco et al., 2021; LeCroy, 1988; Yucel & Yuan, 2016) supporting the importance of quality of parent–adolescent relationships (e.g., intimacy, closeness, connectedness) in promoting adolescent well-being and quality of life. Specifically, when adolescents feel closer to their parents, they are more likely to perceive intimacy and love with their parents, which are essential features in promoting life satisfaction (Pavot & Diener, 2008; Proctor et al., 2009).

Partly consistent with previous studies (Shek, 1997; Zhao et al., 2015), we found a negative association between parent–adolescent conflict and life satisfaction only at the within-family level. This result suggests that higher-than-usual conflicts with parents were more closely linked to adolescents' life satisfaction than the average level of parent–adolescent conflict. Another interpretation may be that parent–adolescent conflicts are an early risk factor for adolescents' decreased satisfaction, especially for those with relatively low conflicts, such as our sample. These results also lent support for our emphasis on disaggregating the within- and between-family associations. Thus, daily changes in parent–adolescent conflict may have more significant impacts on same-day life satisfaction among adolescents than the average level of parent–adolescent conflicts.

As hypothesized, the present findings showed the moderating role of adolescent emotion dysregulation in the associations between daily parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction. Previous research on differential susceptibility has indicated that children with higher levels of negative emotionality or difficult temperament (e.g., irritability) displayed greater sensitivity to both positive and negative contextual factors (Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, et al., 2011; Pluess et al., 2018; Roisman et al., 2012). In line with the notions of differential susceptibility, adolescents with higher emotion dysregulation were more sensitive to daily changes in parent−adolescent relationships. Within-family changes in parent–adolescent closeness and conflict had stronger associations with life satisfaction for adolescents with high emotion dysregulation than those with low emotion dysregulation. Consistent with past research (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Mennin et al., 2007), emotion dysregulation may represent increased emotional reactivity that augments the influences of parent–adolescent relationship fluctuations on adolescents' daily well-being. As such, adolescents higher in emotion dysregulation were more likely to report higher or lower life satisfaction on days when their relationships with parents were closer or more conflictual. Therefore, our findings suggest that emotion dysregulation may reflect heightened differential susceptibility, in which adolescents are more sensitive to daily changes in closeness and conflict with their parents.

Results also showed that emotion dysregulation did not moderate the associations between average parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction. The findings suggest that the effects of average parent−adolescent closeness and conflict on adolescents' life satisfaction were not dependent on the levels of emotion dysregulation. Instead, the moderation effects of emotion dysregulation were only evident at the within-family level, supporting that within-family processes may differ from between-family relationships (e.g., Kapetanovic et al., 2019; Van Lissa et al., 2019). Given the importance of emotion dysregulation in adolescent development, this study extended previous findings by examining its moderating role on life satisfaction at both within-family and between-family levels. The findings showed that parent–adolescent closeness and conflict effects vary at the within-family level, depending on adolescent emotion dysregulation.

4.1 Limitations

Although this study provides several important insights, it has limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, similar to many studies using daily diary methods, adolescent self-reports could be subject to bias (Herres et al., 2016; Silk et al., 2003). Future research would benefit from collecting multi-informant data, such as parent reports of parent–adolescent relationships, and examining their associations with adolescent life satisfaction. Second, the study was limited to school days from Monday to Friday. Future studies should consider whether parent–adolescent relationships have different impacts on adolescent life satisfaction on weekends. Third, previous studies suggest that the effects between parent–adolescent relationships and adolescent well-being may be bidirectional, indicating adolescents are active agents in affecting their relationships with parents (e.g., Chiang & Bai, 2022b; Fanti et al., 2008). It is unclear in the current study whether adolescent life satisfaction also influenced parent–adolescent relationships. Last, we recruited adolescent participants in Taiwan, which may limit the generalization of the results to other cultures and regions. For instance, research has shown that compared to independent and egalitarian values in Western families, Taiwanese families tend to emphasize the interdependence between family members (Chiang & Bai, 2022a). This may exacerbate the close links between family relationships and adolescent psychological well-being across adolescence. Future research should examine the associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction with diverse families (e.g., different types of families, cultures, and nationalities).

4.2 Implications and conclusion

The present findings have several theoretical and practical implications for adolescent well-being. First, the results underscore the importance of parent–adolescent relationships in adolescents' daily lives. Adolescents' daily life satisfaction varies when they experience changes in parent–adolescent closeness and conflict. From a developmental perspective, this study supports the central role of parent–adolescent relationships in influencing child psychological well-being and optimal development during adolescence. Second, investigating positive (closeness) and negative (conflict) aspects of parent–adolescent relationships contribute to the existing literature on family processes, in which adolescents' interactions with parents have critical implications for adolescent development. Third, this study utilized a daily diary methodology to capture the concurrent associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction in the everyday lives of adolescents. The findings highlight the importance of assessing adolescent life satisfaction and well-being as day-to-day processes, during which adolescents develop in response to changes in family relationships. Finally, the current study offers new insights into the pivotal role of emotion dysregulation that can shape how daily fluctuations in parent–adolescent relationships affect adolescents. As such, there is a closer link between emotionally dysregulated adolescents' life satisfaction to parent–adolescent closeness and conflict than emotionally well-regulated adolescents.

Furthermore, this study has practical implications for family-based preventions, interventions, and policies for improving adolescent life satisfaction. These results support the perspective of family relationships as a risk and protective factor for the adolescent quality of life. Prevention and intervention efforts should facilitate adolescents' overall feelings of closeness with their parents, and prevent or de-escalate the times when parent–adolescent conflicts are higher than usual. For instance, school counselors and psychologists can focus on promoting family-based interventions by working with families, as well as identifying adolescent emotion dysregulation (e.g., Chen et al., 2018). Although adolescents high in emotion dysregulation reported lower life satisfaction on days when parent–adolescent conflicts were higher than usual, they also reported higher life satisfaction on days when parent–adolescent closeness was higher than expected. Thus, prevention and intervention programs should focus on adolescents' emotion regulation abilities to provide optimal delivery of family risk assessments and interventions. Finally, policymakers should encourage innovative methodologies such as daily diaries used in this study to understand adolescents' developmental processes in everyday life.

To our best knowledge, this study was the first to test the day-to-day associations between parent–adolescent relationships and adolescents' life satisfaction and the moderating role of emotion dysregulation in these links. The results suggest that parent–adolescent closeness contributes to adolescent life satisfaction at daily and average levels, whereas day-to-day parent–adolescent conflicts have adverse effects on life satisfaction. Emotion dysregulation plays a moderating role, such that daily associations between parent–adolescent relationships and life satisfaction were stronger for more emotionally dysregulated adolescents. The findings have implications for enhancing prevention and intervention programs that aim to promote family relationships and adolescent well-being, such as mitigating within-family changes in parent–adolescent conflicts and adolescents with vulnerable characteristics (i.e., emotion dysregulation). Our findings underscore the importance of examining parent–adolescent relationships in daily life and add to our understanding of family and individual characteristics that shape life satisfaction during adolescence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Shou-Chun Chiang was supported by the Prevention and Methodology Training Program (T32 DA017629; MPIs: J. Maggs & S. Lanza) with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. Data collection was supported by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 110-2410-H-004-109). MOST had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved and carried out under the Institutional Review Board of the National Chengchi University (NCCU-REC-202105-I038). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.