Dual process in parent–adolescent moral socialization: The moderating role of maternal warmth and involvement

Abstract

Introduction

It has been argued that moral identity can be conceptualized as implicit and automatic or explicit and controlled dualities of cognitive information processing. In this study, we examined whether socialization in the moral domain may also exhibit a dual process. We further tested whether parenting that is warm and involved may play a moderating role in moral socialization. We assessed relations between mothers' implicit and explicit moral identity, warmth and involvement, and the prosocial behavior and moral values of their adolescent children.

Methods

Participants were 105 mother–adolescent dyads from Canada, with adolescents between 12 and 15 years of age and 47% girls. Mothers' implicit moral identity was measured using the Implicit Association Test (IAT), adolescents' prosocial behavior was measured using a donation task, and the remaining mother and adolescent measures were self-reported. Data were cross-sectional.

Results

We found that mothers' implicit moral identity was associated with adolescents' greater generosity during the prosocial behavior task, but only when mothers were warm and involved. Mothers' explicit moral identity was associated with adolescents' more prosocial values.

Conclusions

Moral socialization may occur through dual processes, and as an automatic process may only take place when mothers are also high in warmth and involvement, setting the conditions for adolescents' understanding and acceptance of the moral values being taught and ultimately their automatic morally relevant behaviors. Adolescents' explicit moral values, on the other hand, may be aligned with more controlled, reflective socialization processes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Considerable research has addressed the question of how children acquire moral values, beliefs, and actions through the assistance of their parents. A general conclusion is that agents of socialization, such as parents, successfully promote their children's internalization of moral values (their acceptance of these values as internally motivated and as reflecting their own viewpoint) in two ways: by rewarding and modeling moral behaviors and by talking with their children about the importance of moral values. Work supporting this premise shows that adolescent children of parents who volunteer and donate are likely to do the same (Ottoni-Wilhelm et al., 2014), even as adults (Mustillo et al., 2004), and that parents and their children tend to share similar prosocial orientations (Headey et al., 2014; Soenens et al., 2007; Yaban & Sayil, 2021). Parenting behavior that produces these positive outcomes is motivated or guided by the parent's moral identity, that is, by the extent to which parents see morality as a central part of their self-concept. Parents who have a strong moral identity are likely to engage in socialization behaviors that promote moral values because such actions emerge naturally and consistently through a need to act consistently with their identity (Blasi, 2004; Emde et al., 1991).

In the present study, we examined moral identity as reflected in a dual process model of cognitive information processing. A dual process model posits cognition as involving an automatic and impulsive process that may be relatively more implicit, and a controlled and reflective process that may be relatively more explicit (e.g., Deutsch & Strack, 2006; Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977). In this view, parents' implicit and explicit moral inclinations may be linked to different child implicit and explicit outcomes in turn. In the present study, we examined this hypothesis by investigating the relation between mothers' implicit and explicit moral identity and two manifestations of outcomes for their adolescent children: prosocial behavior in the form of generosity to needy others and guided by implicit values, and self-reported values that are guided by explicit values. We also investigated the moderating role of the mother–child relationship in associations between maternal explicit and implicit moral identity and these child outcomes.

1.1 Implicit and explicit moral identity

A substantial body of research has applied the dual process approach to moral cognitions, with moral decision-making proposed to be guided by both automatic and controlled processes (e.g., Greene, 2009; Guglielmo, 2015; Lapsley & Hill, 2008). In line with this view, there is evidence that implicit and explicit moral identity have different moral correlates. Thus, Perugini and Leone (2009) found that an implicit measure of moral identity predicted resistance to temptation (return of a mistakenly received lottery ticket) in young adults whereas an explicit measure did not. In contrast, the explicit measure predicted moral responses to hypothetical vignettes whereas the implicit one did not. M. E. Johnston et al. (2013) found that implicit moral identity was a predictor of physiologically measured moral outrage whereas explicit moral identity was not. In contrast, the explicit measure predicted self-reported religiosity whereas the implicit one did not.

Taken together, these studies support the hypothesis of a dual process model of moral cognition and identity that includes both impulsive-automatic processing and reflective-controlled processing (Deutsch & Strack, 2006). Implicitly measured moral identity is more likely associated with automatic thoughts, emotions, and the behavior controlled by them. Accordingly, in the studies described above, implicit moral identity was linked to automatic reactions such as physiological arousal and spontaneous moral action. On the other hand, explicitly measured moral identity was more closely related to cognitively reflective moral attributes that included responses to hypothetical situations involving moral dilemmas and adherence to formal religious views.

Applying this perspective to the parenting domain, parents' implicit and explicit moral values may also be differently linked to the kinds and forms of moral behaviors they encourage in their children. Research on implicit and explicit parent characteristics in relation to child outcomes is limited. However, the few studies focusing on implicit and explicit parent attitudes have found that mothers' implicit and explicit positive attitudes toward their children are independently linked to less negative parenting (C. Johnston et al., 2017), that less positive implicit attitudes are linked to less maternal sensitivity toward the child (Sturge-Apple et al., 2015), and that activating negative implicit attitudes toward children is linked to more negative views of child behavior (Farc et al., 2008). These findings suggest that implicit cognitive processes in parents, such as implicit moral action, may be linked to more positive socialization practices and, therefore, more positive child outcomes. However, these and other existing studies have yet to explore the socializing role of implicit and explicit parental values independently and their distinct links to adolescent moral value learning.

In the present study, we examined mothers' implicit and explicit moral identity and adolescent prosocial behavior and self-reported values. We reasoned that moral socialization, like moral identity, may involve a dual process approach depending on the implicit or explicit nature of mothers' moral identity. That is, mothers who view themselves as moral individuals more generally would have children who also have strong moral self-concepts. However, mothers with high implicit moral identity should be relatively more consistent and clearer in their displays of moral action by reacting positively to prosocial behavior, by modeling it, and by talking about moral issues. With these clear, multifaceted, and repeated messages to their children that moral action is of singular importance, children would be socialized to hold an internalized moral identity that facilitates behaving in line with moral values. On the other hand, mothers with high explicit moral identity may hold less internalized moral beliefs. Although adept in discussing moral issues with their children, these mothers' teachings would not necessarily be consistent with their behaviors. In turn, children of these mothers would learn to hold explicit moral values but there may be no association with behaving in line with those values.

In consideration of these distinctions, in the present study, we expected that mothers with high implicit moral identity would have children who behaved in line with moral values (prosocial behavior), whereas mothers with high explicit moral identity would have children who reported having highly moral values. These proposed distinctions in socialization of implicit and explicit moral identity would thus extend existing knowledge of socialization by showing that a distinction between automatic and controlled information processing is important in understanding how children acquire moral values (see Bugental & Goodnow, 1998).

1.2 The role of warmth and involvement

Grusec and Goodnow (1994) have argued that, in order for values to be internalized, they must not only be perceived accurately but they must also be accepted. Parents who are consistent and clear in their example and teaching will not be effective unless they set the conditions for reproduction of those actions. In the present study, we assessed the role of warmth and involvement in that reproduction for a variety of reasons. First, warmth in parent–child relationships may lead to children's eagerness to be similar to and to please the parent. Among early adolescent children, warm parenting has been linked to prosocial behavior across many societies (Pastorelli et al., 2016). In particular, when parents use warm and affectionate parenting, particularly in response to adolescents' prosocial behavior, adolescents are more likely to behave prosocially, potentially due to the rewarding nature of the positive interaction with parents (Carlo et al., 2007, 2011).

Second, parents who are warm and responsive establish a more positive environment for internalization of values, whereas highly controlling interactions threaten the child's autonomy and, therefore, undermine feelings of intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017). In line with this perspective, warm and responsive parenting has been shown to increase adolescents' perceived support of their needs (e.g., Ahmad et al., 2013), which in turn has been found to promote adolescent children's prosocial value endorsement (Miklikowska et al., 2011).

Finally, with respect to involvement, involved parents are more likely to have knowledge of their children's activities and can use this knowledge to shape the social environment that would increase their children's positive behavior. Maiya et al. (2020) found that parental involvement was both directly and indirectly related to adolescent prosocial tendencies through less affiliation with delinquent peers and heightened connectedness with teachers and peers at school. The heightened knowledge associated with involvement appears to be particularly important: Kil et al. (2018) reported that, in adolescent-parent pairs who disclosed to one another about distressing events in their everyday lives, adolescents were better able to cope with their emotions and tended to be rated by their teachers as being more prosocial. For these reasons, then, warmth and involvement should facilitate acceptance of prosocial values and actions: only children of mothers who are high in moral identity and high in warmth and involvement would be expected to actually engage in prosocial activity.

1.3 The present study

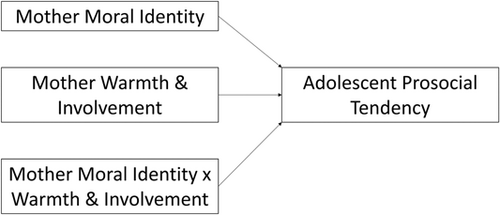

In the present study, we assessed mothers' moral identity using both implicit (task-based) and explicit (questionnaire) measures and examined their association with adolescents' generous behavior (task-based) and with their self-reported values. We predicted that mothers' implicit moral identity would be related to their children's prosocial behavior and mothers' explicit moral identity would be related to their children's self-reported prosocial values, given that different socialization processes may underlie children's understanding of and their behaving in line with moral values. Additionally, we predicted that these links would be significant only when mothers were warm and involved, thereby setting the tone for adolescents' understanding and acceptance of the behaviors or values that mothers embodied. Thus, we expected that mothers' warmth and involvement would moderate the link between mothers' moral identity and adolescents' prosocial tendencies, as depicted in our proposed model (Figure 1). We chose to study adolescents between the ages of 12 and 15 years, as the social and cognitive changes that occur in early to mid-adolescence make this a particularly important time for the socialization and development of morality and prosociality (Eisenberg & Morris, 2004; Steinberg & Silk, 2002).

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Participants

Participants were 105 adolescents and their mothers living in a large Canadian city. Data were collected between 2011 and 2013. Adolescents (56 males, 49 females) ranged in age from 12 to 15 years (M = 13.65, SD = 0.95). Mothers (M age = 46.83 years, SD = 4.10) were primarily of European ethnic origin (78.1%), with others of East Asian origin (11.4%), multiple ethnic origins (5.7%), or other backgrounds (4.8%). All mothers had completed high school and 55.2% had completed college or university; 83.8% of mothers were employed.

2.2 Procedure

All procedures in this study were approved by the university's research ethics board. Mothers who had previously agreed to consider participation in research conducted at a local university were contacted by telephone and provided a description of the study. Mother and adolescent dyads interested in participating were then scheduled for an on-campus session. At the session, mothers were assessed for implicit and explicit moral identity and warmth and adolescents for generosity and self-reported moral values.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Mother explicit moral identity

Mothers completed measures of explicit moral identity using the two subscales of Benevolence and Universalism from the 21-item Portrait Values Questionnaire (Schwartz, 2003; Verkasalo et al., 2009). Benevolence represents concern for the welfare of others (e.g., “It is important to her to be loyal to her friends. She wants to devote herself to people close to her”; “It is important to her to listen to people who are different from her. Even when she disagrees with them, she still wants to understand them”). Universalism represents concern for the welfare of all people (e.g., “She thinks it is important that every person in the world be treated equally. She believes everyone should have equal opportunities in life”; “She wants everyone to be treated justly, even people she doesn't know. It is important to her to protect the weak in society.”). The two subscales fall under the overarching value dimension of self-transcendence (Schwartz, 2003), which has been theoretically and statistically associated with prosociality (Bardi & Schwartz, 2013; Caprara & Steca, 2007). Participants rated their own similarity to a hypothetical gender-matched person who possessed the value on a 6-point scale (1 = not like me at all; 6 = very much like me). To calculate the prosocial values composite score, an overall mean of all 21 items from the PVQ was first computed. This mean was then subtracted from the Benevolence and Universalism scores to obtain the relative importance ascribed to each value. The two relative scores were then summed for the final prosocial values score.

2.3.2 Mother implicit moral identity

Mothers' completed Perugini and Leone's (2009) IAT as a measure of moral identity. The IAT is a computer-based keyboard sorting procedure that has the advantage of reducing self-presentational biases (Greenwald et al., 1998). Mothers were presented with stimulus words in the center of the computer screen and asked to assign these as quickly and accurately as possible to one of two target dimensions (“moral” or “immoral”) and one of two category dimensions (“self” or “other”) using a right or left key stroke. The stimulus words were: honest, faithful, sincere, modest, and altruist (moral) and cheater, dishonest, deceptive, arrogant, and pretentious (immoral) and pronouns referring to the self or others (M. E. Johnston et al., 2013; Perugini & Leone, 2009).

In the critical phase of the task, mothers made a decision for stimuli from the two dimensions simultaneously, with both the target dimension (moral vs. immoral) and the category dimension (self vs. other) presented on the screen. Two types of combinations were presented. In one combination (Set 1), “moral” and “self” were paired on the same side, while “immoral” and “other” were paired on the other side; in the other combination (Set 2), “moral” and “other” were paired and “immoral” and “self” were paired. For instance, the stimulus word “honest” should be sorted to the Moral side of the screen, regardless of whether Moral was paired with Self or Other.

Scores of moral identity rest on the assumption (consistent with the IAT literature) that those with a higher moral identity will be faster to sort “honest” and other moral stimuli into the Moral category when it is paired with Self than with Other. Average response latencies for Set 1 and Set 2 combination phases were calculated using the D600 algorithm for IAT scoring (see Greenwald et al., 2003). Difference scores obtained by subtracting Set 1 latencies from Set 2 latencies were used as the final scores of moral identity. Positive scores indicate higher moral identity (shorter response latencies to Set 1) whereas negative scores indicate lower moral identity (longer response latencies to Set 1). This measure has been shown to predict moral behavior (lying, cheating) and moral affect in the form of anger aroused by a conversation criticizing displays of prosocial behavior (M. E. Johnston et al., 2013; Perugini & Leone, 2009). Perugini and Leone (2009) found reasonable reliability of the moral identity IAT in their sample of adults (α = .68–.83), reasonable test–retest correlations (r = .67), and predictive validity in correlations with task measures of honesty and cheating. Split-half reliability in this work following steps outlined by Kurdi et al. (2019) was 0.57, which was considered acceptable. However, no participants showed signs of random responding, such as excessive errors or short latencies, and as such we retained the full sample despite the modest internal reliability score.

2.3.3 Mother warmth and involvement

Mothers completed a measure of warmth and involvement using the 11-item Warmth and Involvement subscale of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ; Robinson et al., 2001). This subscale assesses mothers' responsiveness and affection toward their children as well as knowledge about their children's lives, for example, “I have warm and intimate times together with my child,” “I am aware of problems or concerns about my child in school.” Items were rated on a 5-point scale from never (1) to always (5), and averaged for a final score of warmth and involvement. Interitem reliability as indicated by Cronbach's alpha was α = .75.

2.3.4 Adolescent generosity

Adolescents completed a donation task as a measure of generosity. As a token of appreciation, all adolescents were given an envelope containing a $5 bill, two $2 coins, and a $1 coin at the beginning of the study session. Toward the end of the session, they were given a brief description of a well-known Canadian charity that grants wishes (e.g., a trip to Disneyland) to children with life-threatening diseases. They were directed to look at a display of posters for this charity on the other side of the room, in front of which was a donation box for the charity that was approximately two-thirds full of bills and coins. The box had a slit where money could be inserted. The interviewer indicated that it was the adolescent's choice whether he or she donated any money or not.

To explore the effects of interviewer presence, adolescents were randomly assigned to one of two generosity conditions: private or public. In the private condition, adolescents were left alone in the room and decided by themselves whether to donate. In the public condition, adolescents were asked by the interviewer whether or not they would like to donate and, if willing to donate, were then instructed to do so while the interviewer remained in the room. All money collected throughout the course of the study was donated to the charity. Some adolescents who had their own money in their pockets chose to donate from their personal pocket money rather than or in combination with money given in the envelope. Donations ranged from $0.50 to $10, and the amount donated served as the measure of generosity. Of the 105 adolescents, 77 donated money, with an average donation of $2.57 (SD = $2.76).

2.3.5 Adolescent prosocial values

Adolescents completed a measure of prosocial values using the PVQ, that is, the same measure used to assess mothers' explicit moral identity. Thus, the adolescent prosocial values measure was also an indicator of adolescents' explicit moral identity.

2.4 Analytic plan

Four moderation analyses were carried out using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (Hayes, 2013; Preacher & Hayes, 2004), with each model testing a different combination of maternal moral identity (implicit, explicit) measure matched with an adolescent prosocial outcome (donation, values). We ruled out structural equation modeling due to the small sample size relative to the number of paths to be tested. Mothers' moral identity scores and warmth and involvement were both mean-centered before analyses. Gender and adolescent prosocial values were correlated and so gender was controlled for in the models predicting adolescent prosocial values. Adolescent donation condition (private vs. public) was controlled for in the models predicting generosity, as having the interviewer present resulted in more money being donated (M = $3.37, SD = 3.06) than when the interviewer was not present (M = $1.96, SD = 2.32). Significant interactions between mother moral identity and mother warmth and involvement were probed using the Johnson–Neyman technique (Hayes & Matthes, 2009; Preacher et al., 2006). This procedure defines regions of significance that represent the range of z-scores within which the simple slope of y on x is significantly different from zero at a chosen level of significance (α). A manual adjustment in the Bonferroni method was applied to account for multiple tests (two per outcome), with a p value cut-off for significance set at .025.

3 RESULTS

Descriptive statistics and correlations are depicted in Table 1. Mothers' implicit moral identity was positively associated with adolescent generosity. Mothers' explicit moral identity was positively correlated with adolescent prosocial values. Adolescent age was correlated with less mother warmth and involvement. Adolescent generosity and adolescent reports of their prosocial values were positively correlated. Adolescents' own reports of their prosocial values were higher for girls than for boys.

| M | SD | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | M implicit MI | −62.18 | 328.20 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.26** | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.13 |

| 2. | M explicit MI | 1.56 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.23* | −0.01 | −0.07 | |

| 3. | M warmth and involvement | 4.29 | 0.40 | −0.06 | 0.12 | −0.23* | −0.01 | ||

| 4. | A generosity (donation) | 2.57 | 2.76 | 0.21* | 0.04 | 0.15 | |||

| 5. | A prosocial values | 0.75 | 1.12 | 0.15 | 0.23* | ||||

| 6. | A age | −0.01 | |||||||

| 7. | A sexa |

- Abbreviations: A, adolescents; M, mothers; MI, mothers' moral identity.

- a Male = 1, Female = 2.

- * p < .05

- ** p < .01.

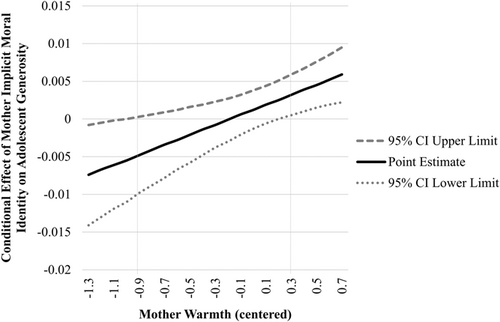

Results of all moderation models are depicted in Table 2 and were largely in line with our hypotheses. First, mothers' implicit moral identity and mother warmth and involvement were not significant predictors of adolescent generosity once all variables of interest were entered into the model. However, there was a significant interaction effect. As depicted in the Johnson–Neyman graph in Figure 2, at higher levels of warmth and involvement (centered score of 0.21 and higher), mothers' implicit moral identity was a significant positive predictor of adolescent generosity, B ≥ 0.003, p < .05, while at lower levels (centered score −1.00 and lower), the association was negative, B ≤ −0.01, p < .05. Second, mothers' explicit moral identity was a significant predictor of adolescents' more prosocial values, echoing the correlation results. However, mothers' warmth and involvement did not significantly predict adolescent prosocial values, directly or in interaction with mothers' explicit moral identity. Finally, neither the direct nor interaction effects with warmth and involvement were significant for mothers' implicit moral identity on adolescent prosocial values or mothers' explicit moral identity on adolescent generosity.

| Models with implicit MI | Models with explicit MI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | B | SE | t | p | |

| Adolescent generosity | ||||||||

| Public/Private (covariate) | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.96 | .34 | 1.55 | 0.54 | 2.84 | .006 |

| Mother implicit MI | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.90 | .37 | ||||

| Mother explicit MI | −0.08 | 0.30 | −0.26 | .80 | ||||

| Mother warmth and involvement | −0.45 | 0.67 | −0.67 | .51 | −0.34 | 0.71 | −0.48 | .63 |

| Interaction (MI × WI) | 0.01 | 0.002 | 3.01 | .003 | −1.12 | 0.81 | −1.39 | .17 |

| Adolescent prosocial values | ||||||||

| Gender (covariate) | 0.48 | 0.22 | 2.21 | .03 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 2.69 | .009 |

| Mother implicit MI | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.40 | .69 | ||||

| Mother explicit MI | 0.30 | 0.12 | 2.57 | .01 | ||||

| Mother warmth and involvement | 0.39 | 0.29 | 1.38 | .17 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 1.08 | .28 |

| Interaction (MI × WI) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.03 | .30 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.51 | .61 |

- Note: Four process models are depicted: models using Implicit MI as “predictor” with the two separate adolescent prosocial “outcomes” appear on the left set of columns, while models using explicit MI as “predictor” with the same separate “outcomes” appear on the right set of columns. Significant paths are bolded to aid interpretation.

- Abbreviations: MI, moral identity; WI, warmth and involvement.

4 DISCUSSION

In this study we asked how adolescents' self-reported prosocial values and their prosocial behavior might be linked to their mothers' moral values and features of the mother–adolescent relationship. Our findings were generally in line with our hypotheses and with dual process models of moral cognition. First, we found that mothers' implicit moral identity was a positive predictor of adolescent generosity, particularly when mothers were high in warmth and involvement. This finding suggests that mothers who endorse moral values and actions and who also set the socialization conditions (warm, responsive) for teaching those values and actions will have adolescents who behave prosocially. Based on the Johnson–Neyman values, we also found modest evidence for active rejection of values involving donation behavior in the case of negative forms of parenting. In line with existing socialization literature (e.g., Van Petegem et al., 2015), our findings suggest that when parents have highly internalized moral values (implicit moral identity) and also behave in line with those values even with their children (warm and involved parenting), children may better internalize parental values and act in accord with them (generosity). Further, echoing previous work with adolescents (e.g., Hardy et al., 2008; Michalik et al., 2007), our results point to a particular emphasis on parental warm and engaged behaviors as crucial for children's moral tendencies.

Second, we found that mothers' explicit moral identity was a significant predictor of adolescents' own self-reported values. In this case, the association was not dependent on levels of warmth and involvement, contrasting some existing work suggesting that more authoritative parenting is linked to higher parent–adolescent prosocial value concordance (e.g., Pratt et al., 2003). This finding suggests perhaps a more direct route of value transmission from mothers' explicit moral identity to adolescents' own developing explicit moral identity, as opposed to the more complex associations between mothers' implicit moral identity and adolescents' observed prosociality that may be dependent on contextual aspects of the mother–child relationship. These findings largely echo existing work showing moderate, significant correlations in self-reported prosocial orientations between adolescents and their parents (Soenens et al., 2007; Speicher, 1994; Yaban & Sayil, 2021). It is possible that when mothers explicitly state their moral values publicly and in the presence of their children, children come to learn that those are more socially acceptable values. Thus, when asked to state how prosocial they are on a questionnaire form in the lab, a public setting, children may respond in line with their mothers' stated values, thereby showing social desirability bias (Fisher & Katz, 2000). This may be particularly true for adolescents, who have a heightened sensitivity to social norms as well as a growing need for social belonging (Telzer et al., 2018). For example, Pratt et al. (2003) reported that parent demandingness was linked to adolescents' higher self-reported ratings of prosociality; the present study may echo a similar process in which adolescent children of parents who preach (Spinrad et al., 2019) prosocial values may respond with higher self-reported prosocial values. However, we note that prosocial giving tasks such as the one used in the present work are also affected by social desirability bias: donation tasks in the lab setting may not always translate to real-world generosity.

These different results for implicit and explicit moral identity provide further evidence for a dual process model of moral cognition (e.g., Greene, 2009), highlighting the importance of distinguishing between the reflective, controlled aspects of moral identity (explicit) and the automatic, spontaneous components (implicit). Both components of mothers' moral identity appear to be associated with their adolescents' prosociality, but in distinct ways and with different forms of prosociality. In particular, mothers' implicit moral identity seems to be conditionally linked to adolescent prosociality: only when mothers parent in a warm and involved way that facilitates adolescents' acceptance and willingness to engage in prosocial behavior (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994), do adolescents appear to share their mothers' prosocial inclinations and embody these values in their behavior.

There has been considerable research on the development of moral identity during adolescence, with results underlining the importance of parenting styles in its facilitation (Hardy et al., 2010; Hart & Atkins, 2004; Pratt et al., 2003). The present study is the first to look at how individuals with already developed moral identities might pass on that identity, or the beginnings of that identity, to their offspring. We found that, at least for our implicit measure, moral identity interacted with one particular parenting style—warmth and involvement—in affecting adolescent outcomes. There are no doubt other styles of parenting that would also act as moderators of a link between parent moral identity and adolescent moral outcomes. These include parenting that is seen as appropriate and fair by the adolescent as well as parenting that does not threaten the adolescent's feelings of autonomy. These are conditions that might lead, for example, to feelings that value systems have been self-generated and that behavior is guided by intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

We suggest that parent moral identity affects many different aspects of parenting: how parents discuss moral issues with their children, their emotional reactions to antisocial behavior, their parenting goals and the goals they set for their children, as well as the models of prosociality that they provide. There is support for this contention in a number of findings with respect to the positive relation between moral identity and behavior (Frimer et al., 2012; M. E. Johnston et al., 2013; Narvaez et al., 2006; Perugini & Leone, 2009). To build upon this argument, research is required to identify the specific mechanisms through which the abstract construct of “moral identity” in parents relates to parenting, in turn leading to different developmental outcomes for children.

4.1 Limitations

Our findings pertain to mothers and research questions need to be extended to the role of fathers in moral development. Our sample was relatively well-educated and primarily Western European in ethnicity, and replication of these findings is needed in more diverse contexts. The study was correlational, and the direction of effect may be different from the present conceptualization. For example, perhaps a mother's moral identity is affected by the nature of her child's moral predisposition, although it seems more likely that a mother's self-identity is relatively firmly fixed by early adulthood and not so susceptible to external pressures. This is not to deny that children can be quite effective in changing the value systems of their parents (Kuczynski et al., 2015). Another limitation lies in our measurements. Our adolescent prosocial behavior measure in the form of donations may not reflect purely internalized motivations to be prosocial. Adolescents may have donated due to self-presentation and social desirability biases in an unfamiliar and public setting. Finally, the IAT measure we used to measure implicit moral identity has received criticism due to its often unstable nature and inconsistent associations with conceptually related constructs (Hofmann et al., 2005; Kurdi et al., 2019).

4.2 Conclusion

Previous research has demonstrated that people's moral identity is linked to their moral behavior and emotion in the case of implicit moral identity and to how they talk about their own moral positions and choices in the case of explicit moral identity. In contrast, implicit moral identity is not linked to talking about moral choices and explicit moral identity is not linked to behavior and emotion (M. E. Johnston et al., 2013; Perugini & Leone, 2009). In the present study we expanded on these known dual process links in the family context. We found that mothers high in implicit (automatic) moral identity have adolescents who are more generous, but only when mothers also show high warmth and involvement. Mothers high in explicit (controlled) moral identity have adolescents who report placing greater importance on prosocial values (an indicator of their own developing explicit moral identity). The results extend the dual process model, focusing on moral identity in a parent–child socialization context. The findings of this study suggest that there are different forms of prosociality and that there are different ways prosociality is socialized, with some more effective when positive parenting coincides.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant to the third author from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The participation of families in the research is deeply appreciated as is the work of undergraduates who contributed to data collection. Megan Gath is now at the Child Well-being Research Institute, University of Canterbury, New Zealand.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.