Aging, inadequacy, and fiscal constraint: The case of Thailand

Abstract

We use an overlapping generations model to study the challenge in developing countries with a large informal sector and aging population. We use Thailand as a case study and incorporate its labor market structure and its public pension system into the calibrated model. Unlike developed countries, workers in developing countries commonly transit from the formal sector to the informal sector, which can be in the early stage of their working life. This labor market feature crucially limits the coverage of the contributory social security (SS) system. We find that 66% of Thai elderly (aged 60 or over) are ineligible for SS annuity benefits because of an insufficient number of years paying into the SS fund. In addition, we use our model to evaluate two schemes to raise the existing universal basic pension income to the poverty line, namely, uniform benefits and pension-tested benefits. We find that pension-testing effectively improves the targeting efficiency, and nontrivially lowers the cost of the basic pension income program.

1 INTRODUCTION

Compared to rich industrialized nations, several middle-income developing countries experienced a much faster rate of population aging. For instance, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand saw their elderly shares double in just 20 years, whereas it took the United States and the United Kingdom 69 and 45 years, respectively, for the share of the population aged 65 or over to double from 7% to 14% (World Bank, 2015). Despite experiencing a rapidly aging population, these middle-income countries suffered late implementation of compulsory public pension programs. Thus, unlike rich developed counterparts, the public pension system in these middle-income countries faces more challenges and must address dual problems, namely, its fiscal sustainability and its large coverage gap.

The reforms to achieve the fiscal sustainability of the public pension system in rich developed countries have been extensively studied in the existing literature. However, what we learned from these studies cannot be applied to developing countries where the labor market is strikingly different with typically sizeable informal sectors (see e.g., Duflo & Banerjee, 2011; La Porta & Shleifer, 2008) and there is a large pension coverage gap (Palacios & Knox-Vydmanov, 2014). In addition, the mandatory retirement age and age discrimination commonly seen in their formal sector make a typical reform of raising the full pensionable age a less compelling option to sustain the social security (SS) program and close the pension coverage gap.

Our study is among the few to develop an overlapping generations model to assess public pension schemes for developing countries featuring an aging population and a large informal sector where workers are not subject to income tax filing and compulsory SS contributions.1 An important model component is the dynamics between formal and informal sectors; one starting their working life in the formal sector can exit to the informal sector later on. While early literature views the formal and informal sectors as dual disconnected labor markets (Rauch, 1991), recent studies document that workers switch between the two sectors throughout their lives (Bosch et al., 2007; Meghir et al., 2015). Since individuals' pension benefits depend on the number of years they contribute to the SS program, the transition between sectors is an important feature for accurately evaluating pension reforms in developing countries.

Our full life-cycle model is developed for the Thai economy. Compared to other middle-income countries, the population aging in Thailand is at the forefront while its SS system, which is a combination of a compulsory SS program for formal workers and a universal basic pension income or old-age-allowance (OAA), was introduced only around 20 years ago. Unlike the SS program, every elderly is entitled to the OAA after reaching a certain age. Both schemes, however, have been criticized as outdated due to the lack of indexation to wage growth and inflation. Consequently, their benefit values have diminished over time (see, e.g., ILO, 2022; World Bank, 2021). In addition, even with indexation, many parties believe that the universal pension benefit is inadequate. In the past few years, there were at least eight bills proposing to increase its benefit amount.2,3

We construct an overlapping generations model of the Thai economy which matches several features in the data related to labor supply, consumption, and accumulated wealth across educational groups and over life-cycle, and use it to study (i) the fiscal sustainability of the SS and OAA programs after indexing benefits to wage growth and (ii) the reforms to increase the OAA from currently 600–1000 THB per month to 3000 THB (approximately the poverty line or 16% of GDP per capita).4 The OAA program is currently funded by the general government revenue, and we assume that the government increases consumption tax (or VAT) to finance its reform.

Our study delivers three sets of key results. We first document that the fraction of formal workers is quickly declining with age. From the social security administrative data, the exit from the formal sector to the informal sector is noticeably higher among the younger age groups. Since the SS benefits depend on the duration in the formal sector, our documentation implies that reforming the SS program alone will be insufficient to provide a pension income for many formal workers who exit early to the informal sector. The simulation from our life cycle model shows that, in the long-run aging population, 66% of people older than 60 years are ineligible for the SS annuity benefits and exposed to longevity risk even after the SS program is financially sustainable. Thus, without a drastic change in the Thai labor market structure, a typical reform to raise the eligible age for SS benefits will have a marginal effect on the SS coverage. A more feasible option to close the coverage gap is to reform the universal basic pension or OAA program.

Second, we find that indexing the existing SS and OAA programs are costly. It requires a substantial hike in SS contribution after the SS fund is depleted in 2045. In the long run aging economy, both employers' and employees' contributions must be increased from currently 3% to over 20% to balance the SS budget. In addition, indexing the OAA to wage growth will quickly raise the public debt to the debt ceiling (60% of GDP) in 2035, and the consumption tax must be increased by 1.4% (from currently 7% to 8.4%) to finance its long-run cost (2% of GDP).

Third, once introducing a uniform increase of the OAA benefits to the poverty line (3000 THB), the program cost rises further to 8.3% of GDP. Consequently, the consumption tax needs to increase substantially to 15.9% in the long run. However, the larger transfer through the OAA benefits brings a large ex ante welfare gain (1.57% of consumption equivalence). The high cost of the uniform benefit scheme is driven by its inefficient targeting. We show that “pension testing” is an effective screening tool to target the elderly in need. Following an ILO proposal, the pension testing will decrease the OAA benefit by 1 THB for every 3 THB of SS annuity income. By introducing the pension testing, the long-run consumption tax needed to finance the OAA reform is lower at 13.6%, while the fraction of elderly (older than 70 years) whose after-tax consumption below the poverty line drops to 3.9%, compared to 4.2% under the uniform OAA benefits. The ex ante welfare gains further increase to 1.63% of consumption equivalence. The additional welfare gain is due to the consumption tax reduction, thus lowering the intra-temporal distortion between consumption and leisure. In addition, the OAA program becomes better targeting by lowering the benefits among the college-educated group who likely have a long career in the formal sector while maintaining the full benefits among the lower-educated groups who likely exit the formal sector soon after entering the labor markets.

Broadly, our paper belongs to literature using a quantitative framework to study the SS system. These studies offer several insights into the SS system in developed countries. Börsch-Supan (2000), French (2005), and Keane and Wasi (2016) studied the effect of SS programs on labor supply, and Zhao (2014) examined the effect of SS program on aggregate healthcare spending. Gustman and Steinmeier (2004), Pashchenko and Porapakkarm (2022), and Coile et al. (2002) studied SS claiming behaviors. Related to ours are Auerbach and Kotlikoff (1987), Imrohoroğlu and Kitao (2012), Kitao (2014), Nishiyama (2015), Huggett and Ventura (1999), Conesa and Krueger (1999), Attanasio et al. (2007), and Kudrna et al. (2019) who, among others, studied the fiscal sustainabilities of the SS programs and reform options. Related to our pension-testing scheme is Bagchi (2023) who found that means-testing can lower the cost of the SS program in the United States.

Closer to ours is a subset of the literature evaluating pension reforms in middle-income developing countries with aging populations. Jung and Tran (2012), Song et al. (2015), and Kudrna et al. (2022) studied the case of Brazil, China, and Indonesia, respectively. Our paper focuses on the pension system in Thailand. In addition, departing from these studies where formal and informal sectors are viewed as parallel labor markets, using the administrative data of the Thai SS program, we document the age- and education-dependent exit from the formal sector to the informal sector and incorporate it into our study. We show that in this environment “pension testing” is an effective screening tool to redistribute from high-educated people who likely work longer in the formal sector to low-educated ones who likely exit the formal sector early.

The article is organized as follows. The next section provides a background of Thai economy and its public pension programs. Sections 3 and 4 present our life cycle model and its calibration, respectively. Section 5 discusses our findings from indexing the SS and OAA program and raising the OAA benefit to the poverty line. The last section provides the conclusion.

2 BACKGROUND OF THAI ECONOMY

2.1 Economic structure

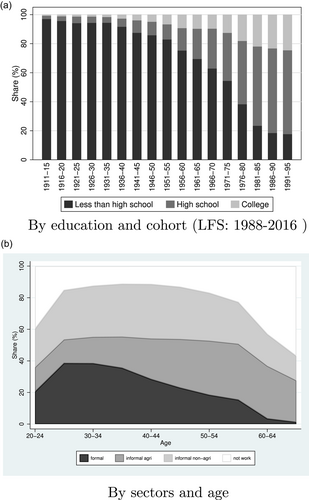

Over the past two decades, the Thai economy grew modestly with an average annual growth rate of GDP per capita at 3.6%. The country is, however, aging rapidly. Between 1980 and 2019, fertility rates declined from 3.4 to 1.5 birth per woman and life expectancy increased from 64 to 77 years. Consequently, the share of the population aged 65 years or older is predicted to double from 13% to 26% in the next 20 years.5 Thanks to its series of educational reforms in 1978, 1999, and 2009, the composition of the later cohorts has shifted from mainly lower than high school toward high school or higher education. As seen in Figure 1a, the share of people without high school degrees for cohorts born before 1960 was more than 75%. For those born in 1990 or later, the share of the high school and college-educated group rose and became stable at around 60% and 20%, respectively.

Concurrently with the education reform, the agriculture sector has largely shrunk from approximately two-thirds to one-third of the labor force. The decline is offset by the rise in shares of the manufacturing, trade, and service sectors with a mix of both formal and informal businesses. Labor force survey (LFS) has information on workers' types of jobs, whether workers contribute to the SS program, and their occupations. In Figure 1b, we classify individuals into agricultural, informal, and formal sectors and report the composition by age in the years 2016–2019. It shows that the share of formal workers quickly declines after age 40. This rapid decline likely reflects a common practice of age discrimination in Thailand, where formal businesses, for example, large corporations, often require job applicants to be younger than 30 or 35 years (Lekfuangfu et al., 2016).

For the rest of the paper, we will define formal workers as those who currently work in registered firms and must participate in the compulsory SS program. In Section 4, we use the SS Administrative data to further document and estimate the education- and age-dependent exit rate from the formal sector.

2.2 Social security (SS) and old-age allowance (OAA) programs

Thailand has three main public pension schemes: the government workers' pension scheme; the contributory SS scheme for formal workers; and the noncontributory OAA scheme.6 We focus on the last two schemes, which cover approximately 90% of the population.

The SS scheme, also known as Article 33, was set up in 1990 as a broad scheme combining together several welfare programs and public insurance programs for formal workers. The initial scheme included unemployment insurance, disability insurance, maternity benefits, and so on (see Table A1 in Appendix A for details). The old-age public pension program of Article 33, or the so-called SS program in our study, was added to the scheme in 1998 and became mandatory for workers in all registered firms in 2002.7 Since its incipient, the number of registered workers increased from 6 million in 2002 (17% of the workforce) to more than 11 million (29% of the workforce) in 2020.

The old-age public pension fund (or called SS fund in this study) receives contributions from three parties, specifically, 3% of earnings from both employees and employers and 1% from the government.8 The maximum SS taxable earnings has remained fixed at 15,000 THB from the start. To be eligible for the SS annuity benefits, SS participants must pay contributions for at least 180 months (15 years). SS members who contributed between 12 and 179 months will receive lump sum benefits which are the sum of their own and their employer's contributions. For those who contributed less than 12 months, their lump sum benefits are equal to the total of their own contributions. The earliest eligibility age to collect their SS benefits is 55 years old. Unlike the SS program in developed countries, there is no benefit adjustment from delaying claims.

All Thai citizens aged 60 years or older, excluding retired civil servants, are eligible for the OAA benefits which were launched in 2009. The program is tax-financed. The initial benefit amounts were 500 THB per month for all age groups but were changed in 2011 to 600–1000 THB, depending on the age of recipients.

There are also three voluntary public pension savings accounts, specifically targeting informal workers, namely: (i) SS Article 39 for those who formerly participated in the Article 33 scheme; (ii) SS Article 40 for those who cannot join the SS Article 39; and (iii) the National Savings Fund (NSF) which was established in 2015. To give incentives to participate in these programs, the government offers a matched contribution. However, the matched rate is relatively small and the overall participation rates in these voluntary programs remain low (see Wasi et al., 2021). Thus, we abstract from these small voluntary pension programs in this paper.

3 MODEL

Our model is a small opened economy where the interest rates are fixed and the average labor productivity exogenously grows at a constant rate to capture the long-run economic growth. The model period is corresponding to 5 years. We use the year 2000 as our base year, which is before the introduction of SS and OAA programs. Afterward, the economy is in transition due to the following forces. First, the population structure is aging and reaches its new stable structure in the year 2200. Second, the SS and OAA programs are introduced in the year 2005, requiring policy variables adjustments to balance budgets.

This section describes our overlapping generations model with two private sectors, namely, formal and informal sectors. To study the effects of the aging population on the SS and OAA programs, we focus on individuals working in the private sector who are the main beneficiaries of the two programs. Their economic model is explained in Section 3.1. In Section 3.2, we discuss the Thai government budgets which also take into account several other spending and revenues not explicitly modeled in Section 3.1.

For convenience, we normalize variables in our model by real GDP per capita. Thus, one unit in our model is corresponding to real GDP per capita in that period.

3.1 Households in private sectors

An individual enters the private labor market at age 25, and can live up to 99 years old with the age-dependent survival probability  . The survival probability is also specific to the birthyear cohort

. The survival probability is also specific to the birthyear cohort  . Denote age as

. Denote age as  where

where  is corresponding to age 25–29 years and the maximum age

is corresponding to age 25–29 years and the maximum age  which is equivalent to 95–99 years old. Individuals are ex ante different in their education level, namely, less than high school, high school, and college:

which is equivalent to 95–99 years old. Individuals are ex ante different in their education level, namely, less than high school, high school, and college:  .

.

and leisure, and derive utility from consumption

and leisure, and derive utility from consumption  and leisure:

and leisure:

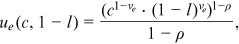

()

() and

and  are the coefficient of relative risk aversion and leisure weights. The future utility is discounted by

are the coefficient of relative risk aversion and leisure weights. The future utility is discounted by  . We set

. We set  to 2.0, which is in the range used in the quantitative macroeconomic literature. To capture different economic outcomes across education groups, we allow

to 2.0, which is in the range used in the quantitative macroeconomic literature. To capture different economic outcomes across education groups, we allow  and

and  to be education-specific and calibrate their values by matching simulated working hours and accumulated assets from our model to the corresponding statistics from the Thai data.

to be education-specific and calibrate their values by matching simulated working hours and accumulated assets from our model to the corresponding statistics from the Thai data.Individuals can save in risk-free assets  and receive a fixed interest rate of

and receive a fixed interest rate of  . We set

. We set  to 4% (per year). We assume that individuals enter the labor market with zero assets. Since we abstract from an intergenerational link, we assume that assets of deceased individuals are equally distributed among living individuals with the same education level.9

to 4% (per year). We assume that individuals enter the labor market with zero assets. Since we abstract from an intergenerational link, we assume that assets of deceased individuals are equally distributed among living individuals with the same education level.9

3.1.1 Formal and informal sectors

During their working age, individuals are exogenously assigned to work in either the formal or informal sectors. Denote  , where

, where  if an individual gets an offer from the formal sector and

if an individual gets an offer from the formal sector and  if otherwise. Informal workers can flexibly adjust their working hours. In contrast, the working hours in the formal sector are inflexible and formal workers can only work full time:

if otherwise. Informal workers can flexibly adjust their working hours. In contrast, the working hours in the formal sector are inflexible and formal workers can only work full time:  . We set

. We set  , which is a fraction of 112 total available weekly hours or equivalent to working 45 h per week.10

, which is a fraction of 112 total available weekly hours or equivalent to working 45 h per week.10

To replicate the declining fraction of formal workers with age as documented in Figure 1, we assume that individuals with a formal job offer can lose their offer in the next period with an education- and age-dependent probability  . Given that the reverse transition rate from being informal workers to formal workers in the data is rather small, we assume that individuals can only continue working in the informal sector till their retirement age after exiting from the formal sector. Thus, being in the informal sector is an absorbing state.

. Given that the reverse transition rate from being informal workers to formal workers in the data is rather small, we assume that individuals can only continue working in the informal sector till their retirement age after exiting from the formal sector. Thus, being in the informal sector is an absorbing state.

Following the mandatory retirement practice in Thailand, we fix the mandatory retirement ages in the formal sector at 55 and 60 years for high school and college groups, respectively. In contrast, those moving to the informal sector before their mandatory retirement ages can continue working till age 70 years.

Note that once reaching their mandatory retirement age, people in the formal sector cannot move to the informal sector. This is consistent with the SS administrative data where there is a large increase in retirement at ages 55 and 60. The assumed large friction to move from the formal sector to the informal sector among older workers can be attributed to the difference in required human capital and skills between sectors. The assumption also replicates the selection into retirement observed in the data. Specifically, those who plan to retire early would choose to stay in the formal sector till their mandatory retirement while those who plan to continue working longer would be better off moving to the informal sector earlier to accumulate new skills.

Everyone working in the formal sector compulsorily participates in the SS program and receives SS benefits once they reach their eligible age  . Depending on the number of years they work and participate in the program, the benefits can be paid either in a lump sum or annuities till death. The benefit amount is calculated from the SS benefit formula described in Section 3.1.3.

. Depending on the number of years they work and participate in the program, the benefits can be paid either in a lump sum or annuities till death. The benefit amount is calculated from the SS benefit formula described in Section 3.1.3.

The earliest eligible age to collect the SS benefits is 55 years old. Since there is no benefit increase from delaying claims, we assume that people who stay in the formal sector collect their benefits at their mandatory retirement ages while SS participants who move to the informal sector take their benefits at age 55.

From age 60 onward, everyone receives OAA benefits  of which amount varies by age. We summarize the retirement age

of which amount varies by age. We summarize the retirement age  and age to collect the SS benefit

and age to collect the SS benefit  and OAA benefits

and OAA benefits  for each group in Table 1.

for each group in Table 1.

| Retirement | SS benefita | OAA benefit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All education in informal sector | 70  |

55  |

60  |

| High school in formal sector | 55  |

55  |

60  |

| College in formal sector | 60  |

60  |

60  |

- a For people ever paying the SS contribution.

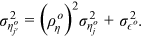

3.1.2 Labor productivity shock

In each period  , working-age individuals aged

, working-age individuals aged  receive a labor productivity shock,

receive a labor productivity shock,  , which depends on age, education, and current working sector. Once they are retired, we set their productivity to zero.

, which depends on age, education, and current working sector. Once they are retired, we set their productivity to zero.

()

() is the average productivity in period

is the average productivity in period  . Denote the exogenous growth rate of

. Denote the exogenous growth rate of  as

as  . We set

. We set  to 3.2% (per year) which is the average growth rate of Thai GDP per capita in 2010–2019.

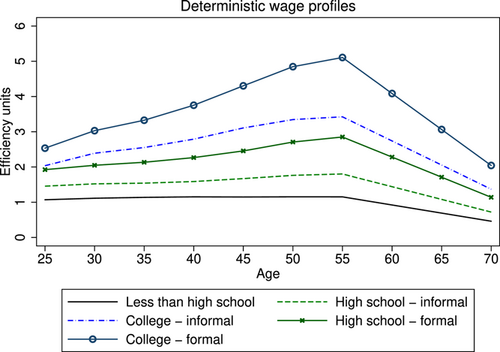

to 3.2% (per year) which is the average growth rate of Thai GDP per capita in 2010–2019.  is the age-dependent deterministic productivity profile, capturing return to experience which differs for each education and sector.

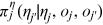

is the age-dependent deterministic productivity profile, capturing return to experience which differs for each education and sector.The persistent productivity shock  follows a first-ordered discrete Markov process. Given the next period sector

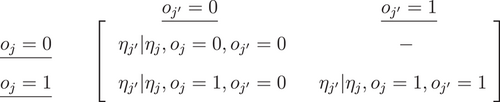

follows a first-ordered discrete Markov process. Given the next period sector  , we denote its conditional transition probability as

, we denote its conditional transition probability as  . Combining this transition probability with the probability to continue being in the formal sector

. Combining this transition probability with the probability to continue being in the formal sector  , we can compute the transition probability from state

, we can compute the transition probability from state  to the next period state

to the next period state  .

.

3.1.3 SS and OAA programs

of 3% of his or her SS taxable earnings.11

of 3% of his or her SS taxable earnings.11

()

() is the maximum earnings subject to SS payroll taxes, which is 15,000 THB. The SS contribution or payroll tax is

is the maximum earnings subject to SS payroll taxes, which is 15,000 THB. The SS contribution or payroll tax is

()

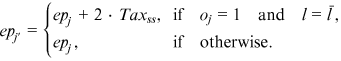

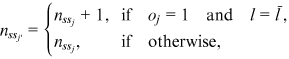

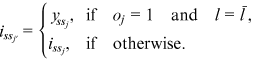

()Once reaching eligible age  , individuals participating in the SS program are eligible for pension benefits. Those contributing less than 15 years (three model periods) will receive their benefits as a lump sum of which amount is equal to their accumulated contribution from both employers' and employees' parts. For those contributing at least 15 years, they receive annuity pension benefits. The annuity amount depends on the number of contributing years

, individuals participating in the SS program are eligible for pension benefits. Those contributing less than 15 years (three model periods) will receive their benefits as a lump sum of which amount is equal to their accumulated contribution from both employers' and employees' parts. For those contributing at least 15 years, they receive annuity pension benefits. The annuity amount depends on the number of contributing years  and the average earnings during the last five contributing years

and the average earnings during the last five contributing years  .

.

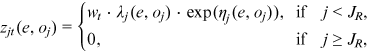

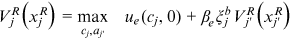

from both employers' and employees' parts, called earnings points, as

from both employers' and employees' parts, called earnings points, as  . For working-age individuals

. For working-age individuals  , the dynamic of accumulated contributions to the next age

, the dynamic of accumulated contributions to the next age  is defined as12

is defined as12

()

() ()

() ()

() , SS participants receive their SS benefits, which is calculated as follows:

, SS participants receive their SS benefits, which is calculated as follows:

()

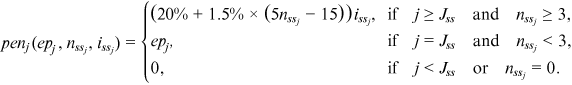

()For SS participants who contribute at least 15 years ( ), their annuity benefits are a fraction (or replacement rate) of their earnings during the last 5 contributing years. The fraction is set to 20% plus 1.5% for each additional year of their contribution after 15 years. Thus, the replacement rate of SS annuity benefits is increasing in the number of contributing years. Those who contribute less than 15 years get a lump sum benefit

), their annuity benefits are a fraction (or replacement rate) of their earnings during the last 5 contributing years. The fraction is set to 20% plus 1.5% for each additional year of their contribution after 15 years. Thus, the replacement rate of SS annuity benefits is increasing in the number of contributing years. Those who contribute less than 15 years get a lump sum benefit  at age

at age  . Since there is no benefit adjustment from delaying their claim, SS participants claim benefits at the eligible ages

. Since there is no benefit adjustment from delaying their claim, SS participants claim benefits at the eligible ages  (see Table 1).

(see Table 1).

In contrast to the SS program where beneficiaries must work in the formal sector and pay their contributions, everyone is entitled to receive OAA benefits once reaching age 60 years.13 The benefit schedule is increasing in age as shown in Table 2.

| Age | Monthly OAA | |

|---|---|---|

| younger than 60 |  |

- |

| 60–69 |  |

600 THB |

| 70–79 |  |

700 THB |

| 80–89 |  |

800 THB |

| 90 or older |  |

1000 THB |

3.1.4 Taxation

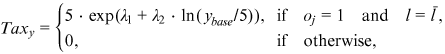

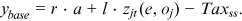

includes both earnings net of the SS contribution and interest income. We parameterize the progressive tax function as follows:

includes both earnings net of the SS contribution and interest income. We parameterize the progressive tax function as follows:

()

() ()

()The parameters  and

and  are estimated from the annual tax filing in 2015–2017 from the Revenue Department. Thus, in Equation (9) we convert the 5-year income tax base into annual income before applying the tax function. In addition, everyone pays consumption taxes (value-added tax). The existing tax rate

are estimated from the annual tax filing in 2015–2017 from the Revenue Department. Thus, in Equation (9) we convert the 5-year income tax base into annual income before applying the tax function. In addition, everyone pays consumption taxes (value-added tax). The existing tax rate  is 7%.

is 7%.

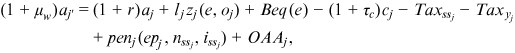

3.1.5 Household's optimization problems

We can now formalize the households' problems during their working age and retirement using the above setup. The time subscript  is omitted to simplify the notation.15

is omitted to simplify the notation.15

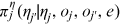

Working-age individuals (j < JR)

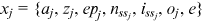

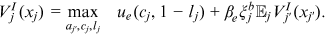

) depending on their education and the current working sector as described in Table 1. In each period, the set of state variables of an individual aged

) depending on their education and the current working sector as described in Table 1. In each period, the set of state variables of an individual aged  in both formal and informal sectors is

in both formal and informal sectors is  . Denote the value function of an individual in the formal and informal sector as

. Denote the value function of an individual in the formal and informal sector as  and

and  , respectively. The recursive problem of an individual in the formal sector is16

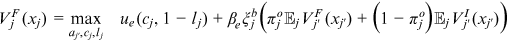

, respectively. The recursive problem of an individual in the formal sector is16

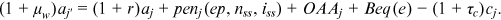

()

() ()

()The utility function  is specified in Equation (1) and the conditional expectations on the RHS of Equations (11) and (12) are over the labor productivity shock described in Equation (2). The term

is specified in Equation (1) and the conditional expectations on the RHS of Equations (11) and (12) are over the labor productivity shock described in Equation (2). The term  in the budget constraint is derived from normalizing the budget equation by the real GDP per capita.

in the budget constraint is derived from normalizing the budget equation by the real GDP per capita.  is the equally redistributed asset of deceased individuals with the same education.

is the equally redistributed asset of deceased individuals with the same education.

The SS contribution  and income tax

and income tax  are defined in Equations (4) and (9), respectively, and only formal workers pay them. Once reaching their eligible ages

are defined in Equations (4) and (9), respectively, and only formal workers pay them. Once reaching their eligible ages  , individuals who previously pay their SS contributions will receive their benefits

, individuals who previously pay their SS contributions will receive their benefits  of which amount is calculated from Equation (8).

of which amount is calculated from Equation (8).

The  is the universal income support for all elderly who are at least 60 years old

is the universal income support for all elderly who are at least 60 years old  .

.  is computed from the monthly benefit schedule in Table 2. In the base year (2000) before the introduction of the SS and OAA systems,

is computed from the monthly benefit schedule in Table 2. In the base year (2000) before the introduction of the SS and OAA systems,  ,

,  , and

, and  are set to zero.

are set to zero.

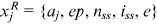

Retirees (j ≥ JR)

. Note that

. Note that  are no longer changed but fixed to the values at age

are no longer changed but fixed to the values at age  . Their recursive problem is

. Their recursive problem is

()

() ()

()3.2 Government budgets

The government runs two separate budgets: the SS program and the general government budget. Since we model only individuals in the private sector, to fully capture the total fiscal budget of the Thai government, we need to add its other revenue sources and spending. We discuss each budget in detail below.

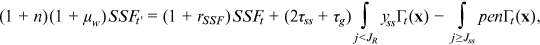

3.2.1 SS budget

The SS program is assumed to be launched in 2005, which is corresponding to the first period during the transition. There are two sources of revenue for the SS fund (SSF). First, both workers and their employers in the private formal sector contribute equally to the fund. Second, the government gives subsidies which are set to  of SS taxable earnings from formal workers.

of SS taxable earnings from formal workers.

Let  be the state variables of households in period

be the state variables of households in period  and

and  is its corresponding measure, of which total measure is normalized to one

is its corresponding measure, of which total measure is normalized to one  .

.

can be written as:

can be written as:

()

() is the fixed rate of return on SSF. We set

is the fixed rate of return on SSF. We set  at 2.24% per year which is the average historical return between 2016 and 2020 (3.61%) subtracted by the average inflation (1.36%).18

at 2.24% per year which is the average historical return between 2016 and 2020 (3.61%) subtracted by the average inflation (1.36%).18

The last term is its spending on SS benefits. The term  and

and  are derived from normalizing the SS budget by GDP. This allows us to conveniently express the aggregate variables as a fraction of GDP. We set the initial

are derived from normalizing the SS budget by GDP. This allows us to conveniently express the aggregate variables as a fraction of GDP. We set the initial  in the year 2005 to zero.19

in the year 2005 to zero.19

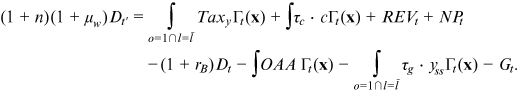

3.2.2 General fiscal budget

Our general fiscal budget replicates the actual structure of government expenditures and revenues during 2000–2020.

Government expenditures

We divide the expenditures into four categories, namely: (i) the debt repayment; (ii) the OAA expenses for individuals in the private sector; (iii) the subsidies related to the SS earnings, and (iv) the general public spending. The subsidy rate to the SS fund  is 1%.20 The general public spending

is 1%.20 The general public spending  includes salaries and pensions of civil servants, the government's consumption and investment, and other public expenses. We assume that the general public spending is a fixed proportion of GDP and the fraction is set to 15.9%, which balances the general fiscal budget in the base year (2000).

includes salaries and pensions of civil servants, the government's consumption and investment, and other public expenses. We assume that the general public spending is a fixed proportion of GDP and the fraction is set to 15.9%, which balances the general fiscal budget in the base year (2000).

Government revenues

In our model, we divide the revenue into four groups, namely: (i) the income tax from the formal workers; (ii) consumption tax from individuals in the private sector; (iii) income tax and consumption taxes from the nonprivate sector, denoted as  ; and (iv) other sources of revenue, denoted as

; and (iv) other sources of revenue, denoted as  . The first two groups are explicitly captured by the private sector in Section 3.1.

. The first two groups are explicitly captured by the private sector in Section 3.1.

For each individual in the nonprivate sector, we assume that one's income tax is equal to the average income tax of formal private workers and one's consumption tax is equal to the average consumption tax of those who start their career in the formal sector, that is, those who receive SS benefits. This assumption reflects the fact that the excluded group—civil servants, state enterprise workers, and employers—are likely in the upper-income groups. To compute the income and consumption taxes from nonprivate sector  , we multiply the average income and consumption taxes by the size of the nonprivate sector relative to the private sector

, we multiply the average income and consumption taxes by the size of the nonprivate sector relative to the private sector  , which is set to the ratio of individuals in the nonprivate sector and the private sector in the LFS data:

, which is set to the ratio of individuals in the nonprivate sector and the private sector in the LFS data:  . Finally, we fixed the revenue from other sources at 9% of

. Finally, we fixed the revenue from other sources at 9% of  , which is the average value during 2000–2020.

, which is the average value during 2000–2020.

. Equation (17) is the general fiscal budget normalized by GDP per capita.21

. Equation (17) is the general fiscal budget normalized by GDP per capita.21

()

() ()

() is the interest rate for government debts. We set

is the interest rate for government debts. We set  to 0.9% (per year) which is the average return of 10-year government bonds during 2015–2020 (2.26%) subtracted by the 10-year average inflation (1.36%).

to 0.9% (per year) which is the average return of 10-year government bonds during 2015–2020 (2.26%) subtracted by the 10-year average inflation (1.36%).

4 PARAMETERS AND INITIAL DISTRIBUTIONS

4.1 Population structure

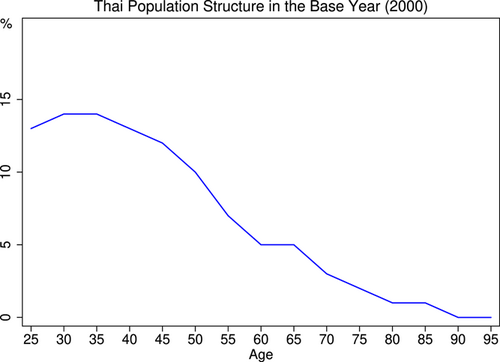

The base year's population structure is assumed to be stationary and constructed from the United Nations (UN) estimates of survival probability  and the shares of the population by age group in the year 2000 (Figure 2).

and the shares of the population by age group in the year 2000 (Figure 2).

Once the economy experiences the aging population from 2005 onward, we introduce cohort-specific survival probabilities and entry rates of new cohorts at age 25.22 Since the UN's projection is only available till the year 2100, we linearly extrapolate the increasing survival rates trend until 2150, after which it no longer changes.

The left panel of Figure 3 presents the survival probabilities of the cohorts living in the base year (2000) and the new entering cohorts during the selected transitional years (2050, 2100, and 2150 onward). Over time, the dependency ratio (population older than 65 divided by population aged 25–65 years) increases from 14% in the base year (2000) to 69% in 2200 (the right panel of Figure 3).

4.2 Formal and informal sectors

4.2.1 Initial distributions (25 years old)

We obtain the educational share of people aged 25–29 from the LFS. The first column of Table 3 reports the education in the base year. We assume that the educational shares of entering cohorts aged 25 years are constant once the transition starts (the second column).

| % of population | % of population | % in formal sector | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (base year 2000) | (2005–2200) | (2000–2200) | |

| Less than high school | 34% | 18% | 0% |

| High school | 47% | 58% | 83% |

| College | 19% | 24% | 100% |

The share of formal workers by education in the LFS, however, remains relatively stable throughout all waves. The last column reports the initial fraction of people working in the formal sector by education in our model. Since only a small fraction of workers with less than high school degree work in the formal sector, we assume all of them are informal workers.

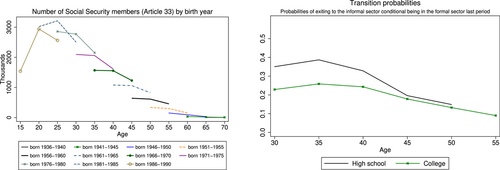

4.2.2 Transition from the formal to informal sectors:

A key feature of our model is that there is a transition from the formal to informal sectors. We utilize both the SS Administrative data (2005–2015) and the LFS data to estimate the age- and education-specific probabilities to leave the formal sector. The SS Administrative data has a large advantage since it contains all SS participants' earnings history till they left their employers in the formal sector. However, it does not have educational information. To impose individuals' education, we turn to the sample of formal workers in the LFS (2016–2019) and estimate an ordered logit model of their education using a set of covariates observed in both the LFS and the SS Administrative data. The covariates in the ordered logit model include wage at age 25, gender, firm size, residence area (urban/rural), and their interactions. Individuals' education in the SS Administrative data is, then, assigned to the most likely education level predicted by our estimated ordered logit model. Finally, for each education and 5-year age group, we estimate  from the corresponding fraction of people who left the program in the SS Administrative data.

from the corresponding fraction of people who left the program in the SS Administrative data.

The left panel of Figure 4 presents the actual number of SS members by age group and birth year. For each birth year cohort, the number of members quickly declined as they are approximately older than 30–35 years old. The right panel of Figure 4 shows the estimated exit probability by education conditional on being in the formal sector last period  . The high school group is more likely to leave the formal sector than the college group. In addition, the exit rate is noticeably high among young workers (around 40% and 25% for high school and college groups, respectively) and continuously declines with age.

. The high school group is more likely to leave the formal sector than the college group. In addition, the exit rate is noticeably high among young workers (around 40% and 25% for high school and college groups, respectively) and continuously declines with age.

(right).

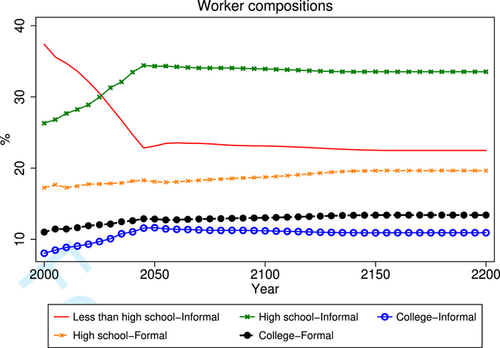

(right).4.2.3 Composition of workers during the transition

Figure 5 shows the changes in education and sector composition of the working-age population. The shares of workers with less than high school, high school, and college degrees converge to 23%, 53%, and 24% around the year 2070, respectively, which is roughly in line with the shares in developed economies. As education improves, the shares of young formal workers increase. But the overall share of formal workers (black line and orange line) only slightly increases because the increasing share of young formal workers is offset by the rising share of older workers who exit into the informal sector.

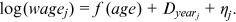

4.2.4 Labor productivity

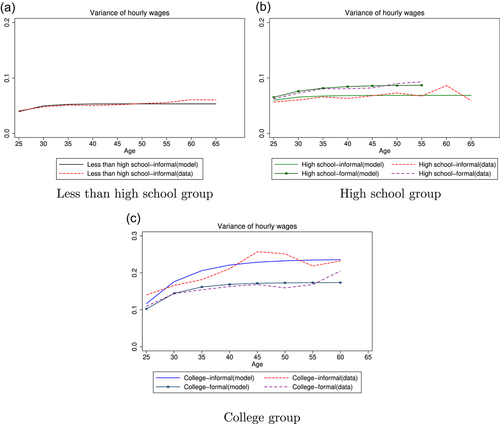

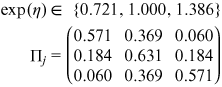

As discussed in Section 3.1.2, our hourly wage shock is characterized by three components: (i) the economy-wide labor productivity  , which exogenously grows at a constant rate

, which exogenously grows at a constant rate  , (ii) the age-deterministic profile

, (ii) the age-deterministic profile  , and (iii) the first-ordered Markov shock process

, and (iii) the first-ordered Markov shock process  . The latter two components are specific to education and sector. For each education and sector, we estimate the profiles

. The latter two components are specific to education and sector. For each education and sector, we estimate the profiles  from age 25 to 55 as a quadratic function of age using the LFS (2016–2019), and assume a linearly declining trend till zero at age 80.23 The profiles

from age 25 to 55 as a quadratic function of age using the LFS (2016–2019), and assume a linearly declining trend till zero at age 80.23 The profiles  are, then, scaled to match the average income of workers by sector and education in the LFS.

are, then, scaled to match the average income of workers by sector and education in the LFS.

for each education and sector from the LFS. In our model, an individual draws his hourly wage shock every 5 years and its 5-year transition can be partitioned into three blocks, depending on the current and next period sectors.

for each education and sector from the LFS. In our model, an individual draws his hourly wage shock every 5 years and its 5-year transition can be partitioned into three blocks, depending on the current and next period sectors.

, we parameterize their hourly wage shock as an AR(1) process:

, we parameterize their hourly wage shock as an AR(1) process:

()

() for each age can be written recursively as

for each age can be written recursively as

()

() by regressing the log-wage equation separately for individuals working in the formal and informal sectors:

by regressing the log-wage equation separately for individuals working in the formal and informal sectors:

and

and  are individual's hourly wage and year-dummy variable.

are individual's hourly wage and year-dummy variable.  is polynomial degree two of age. By assuming that

is polynomial degree two of age. By assuming that  , we can estimate

, we can estimate  and

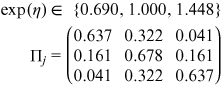

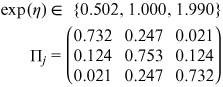

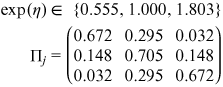

and  by minimizing the sum square difference between the cross-sectional variance in Equation (20) and the corresponding empirical variance from the LFS.24 Table 4 reports our estimates for each education and sector.25 We discretize the estimated AR(1) process into a 3-state Markov process using the Rouwenhorst method. We report the 5-year transition matrix and the corresponding grid values of our hourly wage shock process in Appendix B1.

by minimizing the sum square difference between the cross-sectional variance in Equation (20) and the corresponding empirical variance from the LFS.24 Table 4 reports our estimates for each education and sector.25 We discretize the estimated AR(1) process into a 3-state Markov process using the Rouwenhorst method. We report the 5-year transition matrix and the corresponding grid values of our hourly wage shock process in Appendix B1.

(5-year period).

(5-year period). |

|

|

| Less than high school | 0.039 | 0.5119 |

| High school in informal sector | 0.044 | 0.5965 |

| High school in formal sector | 0.043 | 0.7088 |

| College in informal sector | 0.116 | 0.7111 |

| College in formal sector | 0.102 | 0.6401 |

Since the LFS is cross-sectional, we cannot estimate the hourly shock process of formal workers who exit into the informal sector  . We assume that its discrete Markov process has the same transitional probabilities as workers who consecutively work in the informal sector

. We assume that its discrete Markov process has the same transitional probabilities as workers who consecutively work in the informal sector  .

.

4.3 Preference parameters

We use leisure weight to match the average working hours of informal workers by education in the LFS.26 Discount factors are calibrated to match the net worth of people aged 30–54 by education in the Household Socioeconomic Survey (SES). Table 5 reports the estimated  and

and  by education. As shown in the second column, people from a lower education group put less weight on their leisure. This is driven by the fact that people with low education on average have a lower wage but work longer hours than their higher-educated counterparts. The third column shows that compared to the lower educated groups, the college-educated are more patient and, consequently, have a noticeably more accumulated net worth.

by education. As shown in the second column, people from a lower education group put less weight on their leisure. This is driven by the fact that people with low education on average have a lower wage but work longer hours than their higher-educated counterparts. The third column shows that compared to the lower educated groups, the college-educated are more patient and, consequently, have a noticeably more accumulated net worth.

Leisure weight ( ) ) |

Discount factors ( ) ) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Less than high school | 0.608 | 0.936 |

| High school | 0.608 | 0.941 |

| College | 0.668 | 1.028 |

Tables 6 and 7 compare selected moments from our model and the data.27 The targeted moments are marked with  . The first column in Table 6 shows that the average weekly hours worked by education in the model and the data are well matched, and the lowest educated group works longer hours than the high school and college graduates.28 For high school and college groups, our average weekly working hours are lower than the average hours worked in the LFS because the number of hours per week for all formal workers in our model is fixed. Since everyone in our model starts with zero asset, we target the average net worth among people at least 30 years old. As seen in the first column of Table 7, our model can closely match the targeted net worth among working-age group (30–54 years old).

. The first column in Table 6 shows that the average weekly hours worked by education in the model and the data are well matched, and the lowest educated group works longer hours than the high school and college graduates.28 For high school and college groups, our average weekly working hours are lower than the average hours worked in the LFS because the number of hours per week for all formal workers in our model is fixed. Since everyone in our model starts with zero asset, we target the average net worth among people at least 30 years old. As seen in the first column of Table 7, our model can closely match the targeted net worth among working-age group (30–54 years old).

| 25-54 years old | 55-69 years old | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly hours | Monthly labor income | Monthly consumption | Monthly consumption | |

| Baseline model | ||||

| All | 47 | 8453 | 6221 | 5334 |

| Less than high school | 49* | 5153 | 4127 | 3390 |

| High school | 47* | 7938 | 6039 | 4928 |

| College | 43* | 15,466 | 10,323 | 9714 |

| Thai data | ||||

| All | 45 | 7793 | 5487 | 5898 |

| Less than high school | 49 | 5021 | 3724 | 3574 |

| High school | 46 | 7167 | 5385 | 5954 |

| College | 46 | 14,139 | 8819 | 9818 |

- Note: Income and consumptions are in THB using the year 2000 prices. The weekly hours and labor income data are from the LFS while the consumption is from the SES, which is converted into the individual-level using the OECD adult-equivalence scale. Our targeted moments are denoted by *.

| Baseline model | Thai data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–54 years old | 55–69 years old | 30–54 years old | 55–69 years old | |

| All | 347,007 | 664,480 | 366,898 | 873,507 |

| Less than high school | 195,629* | 344,163 | 199,794 | 372,920 |

| High school | 287,519* | 566,574 | 321,792 | 798,699 |

| College | 754,912* | 1,460,368 | 766,645 | 1,926,420 |

- Note: The values are in THB based on the year 2000 price. The data is from the SES, which is converted into the individual level using the OECD adult-equivalence scale. Our targeted moments are denoted by *.

To externally validate our calibrated model, we report several nontargeted moments (numbers without  ) from our model and compare with the data in Tables 6 and 7. Overall, our model can reasonably replicate the variation on average labor income, consumption, and net worth across education and age groups.

) from our model and compare with the data in Tables 6 and 7. Overall, our model can reasonably replicate the variation on average labor income, consumption, and net worth across education and age groups.

5 RESULTS

In this section, we introduce the aging population, the SS program, and the OAA program into our calibrated model. All changes are unexpected to the households living in the base year. Section 5.1 discusses the indexation of the SS and OAA programs and their fiscal sustainability in the long run. Section 5.2 studies different schemes to increase the basic pension income (OAA).

5.1 Indexing the SS and OAA programs

Due to the lack of indexation of the SS and OAA programs to economic growth, the economic value of the SS and OAA programs diminishes over time and eventually becomes a negligible fraction of average wage and consumption. To maintain the economic value of the programs, we index both SS and OAA programs to the average wage growth. Specifically, the maximum SS taxable earnings  and the OAA benefits

and the OAA benefits  are scaled up by the average wage growth

are scaled up by the average wage growth  .

.

To finance both programs in the aging economy we use the following arrangement. For the SS program, when the SS fund is depleted, we increase both employers' and employees' contributions to balance the SS budget in Equation (16). In addition, the increasing government spending from the OAA program is firstly financed by the government debt ( ). Once the government debt hits the legislative debt ceiling at 60%, we increase the consumption tax

). Once the government debt hits the legislative debt ceiling at 60%, we increase the consumption tax  to balance the general government budget in Equation (17). In our context, the consumption tax is the only feasible tax instrument. Unlike developed countries, the personal income tax base in developing countries with a large informal sector is rather small, and capital gains are commonly under-reported, making it infeasible to raise a large revenue from income-based taxation. In addition, raising earnings tax is often viewed as discouraging formality.

to balance the general government budget in Equation (17). In our context, the consumption tax is the only feasible tax instrument. Unlike developed countries, the personal income tax base in developing countries with a large informal sector is rather small, and capital gains are commonly under-reported, making it infeasible to raise a large revenue from income-based taxation. In addition, raising earnings tax is often viewed as discouraging formality.

5.1.1 Projected costs of indexation

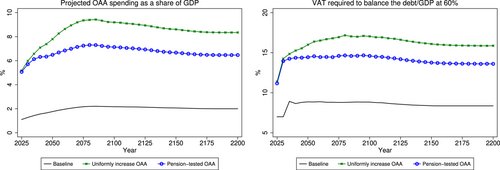

Figure 6 shows the cost projection of the OAA program which is indexed to the wage or GDP growth. Due to the aging population, its spending quickly increases from 2005 when it was introduced. The government debt hits its ceiling in 2035 and the consumption tax has to increase. In the long-run aging steady state (2200), the total spending of the OAA program is almost 2% of GDP which requires an increase in consumption tax from currently 7% to 8.4%.

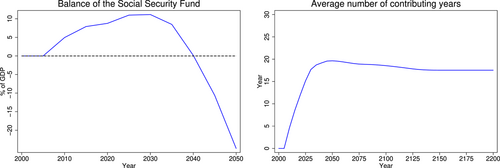

The left panel of Figure 7 reports the projected balance of the SS fund when benefits are indexed to wage growth.29 The fund will be in deficit in 2045, which is less than four decades after its incipient. The rapid depletion of the SS fund is partly due to the aging population as commonly discussed in the case of developed countries. A less discussed reason for the case of Thailand is its nonfinancially viable benefit formula. Specifically, following the earnings profile, individuals' SS contribution increases over age. But their annuity benefits are computed from the last 5 years of contributions, which is likely higher than their average contributions. Thus, as more people start collecting annuity benefits, the SS fund grows slower.30 As shown in the right panel of Figure 7, the average contributing years among people aged 60 years who ever pay SS contributions quickly increases after 2005, thus hastening the depletion of the SS fund. To keep paying the promised benefits in the long run steady state (2200), the contribution rate must considerably increase from 3% to 22.5% (or 45% in total from both employer and employee parts).31

5.1.2 Long-run adequacy of the SS program

Two salient features of the Thai labor market are the mandatory retirement age among formal workers and their exit into the informal sector, which can happen in the early stage of their working life. Accounting for the formal–informal transition for people allows our model to generate a rich heterogeneity in contribution histories, from which SS benefits are calculated. Table 8 presents the long-run distribution of contributing years among the retirees aged older than or equal to 70 years in 2200. The elderly in the lowest educated group is always in the informal sector, hence neither contributing to nor receiving benefits from the SS program. More importantly, even though the majority of higher educated groups enter the labor market as formal workers, 66% (44%) of the high school (college) group pays contributions less than 15 years over their working life and receives benefits as a lump sum payment. Consequently, 66% of the elderly population receives no annuity SS benefit even after the program is indexed and financially sustainable.

) in 2200.

) in 2200.| By education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Less than high school | High school | College | |

|

66% | 100% | 66% | 44% |

|

34% |  |

34% | 56% |

The above result illustrates that once taking into account the structure of the Thai labor market, a reform of the SS program cannot provide sufficient insurance against longevity risk and old-age poverty. In contrast, the basic pension income (OAA) is an entitled program, thus covering all elderly. However, a reform to increase its benefits is costly. In the next section, we discuss different schemes to raise the basic pension income.

5.2 Increasing basic pension income (OAA)

In this section, we consider two schemes to raise the OAA benefits for everyone aged 60 years or above to 3000 THB per month (approximately the poverty line or 16% of GDP per capita); namely: (i) uniform OAA benefits and (ii) pension-tested OAA benefits. Unlike the uniform scheme where every elderly receives the same benefit amount, the OAA benefits are reduced by one THB for every three THB of SS annuity income under the pension-testing scheme. While some developed countries, such as Australia, adopt means-tested pension benefits, pension-testing is readily implementable in developing countries where income and assets are likely under-reported and unverifiable.

Raising the OAA benefits has been currently in debate and proposed to the Thai parliament. Thus, we assume that the OAA benefits increase starts in 2025, which is a few years from now and is unexpected. Similar to Section 5.1, both SS and OAA programs are indexed to wage growth, and in the following discussions, we benchmark their long-run outcomes with the outcomes in the baseline economy with indexation.

5.2.1 Costs of increasing OAA benefits

Figure 8 illustrates the cost of raising the OAA benefits to the poverty line. In the long run steady state (2200), the total spending under the uniform benefits and the pension-tested benefits is equal to 8.3% and 6.5% of GDP, respectively, compared to 2% in the baseline case with indexation. The public debt hits the debt ceiling (60% of GDP) once the OAA benefits increase, requiring a large increase in consumption tax to balance the government budget. The required long-run consumption tax is raised to 15.9% and 13.6% for the uniform and pension-tested benefit cases, respectively. The corresponding tax rate is 8.4% in the baseline case with indexation.

Our results show that while raising the OAA benefits to the poverty line is very expensive, the pension-testing option can help offset the program cost (as a percentage of GDP) and the required increase in consumption tax as large as two percentage points.

5.2.2 Long-run responses of households

The last two columns of Tables 9 and 10 report the households' responses to the increase in OAA benefits in the long-run steady state (2200), whereas the first column is the baseline case with indexation. Overall, people work less and save less when the OAA benefits increase to 3000 THB. The decrease in savings is more pronounced among the high school and lower educated groups for all age groups. Since the OAA benefits are paid out as long as one is alive, it is equivalent to an annuity. As shown in Table 8, a large fraction of high school and lower educated groups pay SS contributions for less than 15 years and receive no SS annuity benefits. The increase in OAA benefits reduces their exposure to longevity risk, consequently lowering their self-insurance through saving.

| Indexation | Indexation + uniform OAA | Indexation + pension-tested OAA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 48 | 47 | 47 |

| Less than high school | 50 | 48 | 48 |

| High school | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| College | 45 | 44 | 44 |

| Indexation | Indexation + uniform OAA | Indexation + pension-tested OAA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30–54 years old | |||

| All | 381,312 | 317,487 | 323,788 |

| Less than high school | 262,073 | 186,947 | 186,947 |

| High school | 236,277 | 173,111 | 178,669 |

| College | 808,090 | 750,835 | 763,409 |

| 55–69 years old | |||

| All | 893,954 | 715,031 | 732,368 |

| Less than high school | 504,108 | 298,135 | 298,135 |

| High school | 621,746 | 445,593 | 461,600 |

| College | 1,814,232 | 1,648,226 | 1,681,141 |

- Note: The values are THB based on the year 2000 prices.

The decreased exposure to longevity risk after retirement partly accounts for the lower labor supply among the working-age population. In our model, the large increase in consumption tax also affects labor supply through the intratemporal distortion. Specifically, when pretax consumption becomes more expensive, people substitute their consumption with leisure, consequently working less.32

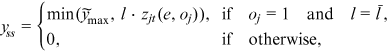

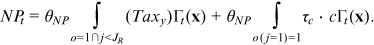

In the following, we use two measures to compare the two OAA schemes: poverty rate among the elderly and ex ante welfare gains/losses. Since the OAA reform directly targets at the elderly, the former is a measurable statistic of interest for policymakers. However, the latter is a more comprehensive measure of the reform outcomes.

5.2.3 Poverty rate reduction

Table 11 compares the poverty rate among retirees older than 70 years in the long run steady state in 2200. We define an elderly living in poverty if her after-tax consumption is below the poverty line. The poverty line in 2200 is constructed by inflating the poverty line in the base year with the average wage growth.

70) in year 2200.

70) in year 2200.| Baseline + indexation | Indexation + uniform OAA | Indexation + pension-tested OAA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 4.8% | 4.2% | 3.9% |

| Less than high school | 16.7% | 14.7% | 12.9% |

| High school | 3.2% | 2.9% | 2.8% |

| College | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Overall, the increase in OAA benefits reduces the poverty rate among the elderly from 4.8% in the baseline to 4.2% and 3.9% under uniform and pension-tested OAA schemes, respectively. The largest reduction is among the lowest educated group. Notice that even though the benefit amount in both schemes is the same, the poverty rate is lower when using pension-testing. This is due to the fact that consumption tax under the pension-testing scheme is lower and the elderly can enjoy a higher after-tax consumption.

5.2.4 Welfare evaluation

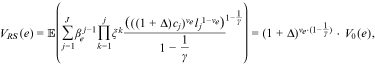

a new entrant at age 25 in the baseline case with indexation is willing to give up to be as well off as if she enters into an economy with the raised OAA benefits. Formally, it is calculated from the following33:

a new entrant at age 25 in the baseline case with indexation is willing to give up to be as well off as if she enters into an economy with the raised OAA benefits. Formally, it is calculated from the following33:

()

() and

and  are the value function of a new entrant with an education

are the value function of a new entrant with an education  in the baseline with indexation and an economy with increased OAA benefits, respectively.

in the baseline with indexation and an economy with increased OAA benefits, respectively.

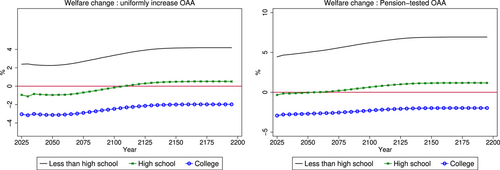

Table 12 presents the long-run welfare gains/losses from the two OAA reforms among people entering the economy after the year 2200. Our welfare measure captures the key trade-off of the reforms. On the one hand, the lump sum transfer through increased OAA benefits creates welfare gains where the gain among the lower-educated group is higher than the higher-educated ones. On the other hand, the increase in consumption tax lowers welfare by distorting individuals' consumption and labor supply decisions.34 The first row of Table 12 shows that overall the former effect is larger. The uniform OAA reform generates a large welfare gain of 1.57% in terms of consumption equivalence. In addition, when introducing the pension-testing scheme, the welfare gain goes up further to 1.63% because of the lower consumption tax distortion and the progressive benefit schedule.

| Uniform OAA | Pension-tested OAA | |

|---|---|---|

| Average | 1.57% | 1.63% |

| Less than high school | 5.5% | 7.5% |

| High school | 1.5% | 1.4% |

| College | −1.2% | −2.1% |

The last three rows of Table 12 report the welfare gains/losses of new entrants at age 25 by education. Under the uniform OAA reform, the lowest educated group benefits most while the college-educated group bears the welfare losses: 5.5% and −1.2% in terms of consumption equivalence, respectively. When introducing the pension-testing, the lowest educated group enjoys a higher welfare gain (7.5%) from the lower consumption tax while the college-educated counterpart incurs a higher welfare loss (−2.1%) since they are now less likely to receive OAA benefits.

Figure 9 shows the ex ante welfare gains/losses across entering cohorts during the transition periods. For all education groups, the welfare gains (losses) among the latter cohorts are higher (less) than the earlier cohorts. Since the OAA benefits are paid out as annuities and the latter cohorts tend to live longer, they value the raised OAA amount more than the earlier cohorts.

6 CONCLUSION

In this paper, we discuss the challenge to provide income support for the elderly in middle-income developing countries with a large informal sector and aging population. Using Thailand as a case study, we develop an overlapping generations model featuring its formal-informal labor market structure and its two public pension programs, namely, the contributory SS program and the universal basic pension income (so-called old-age allowance or OAA). The model is calibrated to match several statistics from Thai data.

We show that if the SS program is indexed to wage growth, its balance is projected to quickly run into deficit in 2045, which is less than four decades after its launch and driven by the rapidly aging population, the late introduction of the SS program, and the annuity benefit formula which is not financially viable. To make the program financially sustainable in the long run, the contribution rate must substantially increase from the current 3% to 22.5% (or 45% in total from both employers' and employees' parts).

More importantly, we document that the exit rate of formal workers to the informal sector is age-dependent, with a high exit rate among young workers. Since only people contributing longer than 15 years are eligible for SS annuity benefits, more than half (66%) of the elderly population (60 years old or above) are ineligible for SS annuity income and exposed to longevity risk even after the program is financially sustainable. Our finding shows that not only the size of the informal sector, but the dynamics between formal and informal sectors are also important in studies of SS reforms in developing countries with an informal sector. Thus, to expand the pension coverage, a typical reform to raise the pensionable age is ineffective while the alternative reform of the universal basic pension or OAA program is more feasible.

While uniformly increasing the OAA benefits for all elderly aged 60 or above can better insure everyone against the longevity risk, it is costly. We illustrate that pension-tested benefits can lower the cost of uniformly increasing OAA benefits to the poverty line (3000 THB) from 15.9% of GDP to 13.6%, and reduce the poverty rate among the elderly (70 years old or above) from 4.2% to 3.9%. In addition, since college graduates are more likely to work and stay in the formal sector while the lower-educated group more likely works in or exits early into the informal sector, the pension-testing scheme allows the program to channel resources toward those with low lifetime earnings and limits the OAA benefits among those with high lifetime earnings.

Overall, our results show that pension-testing can effectively improve the targeting efficiency of the basic pension income program and nontrivially lowers its cost. More importantly, it is readily implementable in countries where other income sources are prone to under-reporting. Unlike the simple linear pension-testing schedule studied here, the optimal pension-testing schedule is likely nonlinear. In our future work, we plan to extend our current framework to examine the optimal pension-testing schedule.

The public pension system in developing countries is an integrated system of contributory and noncontributory programs which, together, provide income support for the elderly with different working histories in formal and informal sectors. Thus, a promising research avenue to explore is a more comprehensive reform that includes all pension programs. This integrated reform can further improve efficiency and, thus, lower the overall cost of the public pension system. Specifically, in the case of Thailand, the replacement rate of SS annuity benefits is increasing in the number of contributing years. Since the number of contributing years is positively correlated with labor income, the existing redistribution within the SS program is regressive; individuals who stay long in the formal sector enjoy both high lifetime earnings and high replacement rates. This is in contrast to developed countries where the replacement rate is declining with lifetime earnings. A reform that makes the SS benefits progressive combined with an increase in pension-tested OAA benefits studied here will likely lower the cost of OAA program further.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank researchers at the ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR), and Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research (PIER) and panelists at the Bank of Thailand Symposium 2021 for useful comments. Coding and computation partly benefited from the discussion with George Kudrna. Financial supports from Australian Research Council linkage grant (LP190100681) and Policy Research Center grant (P222RP212) from GRIPS are acknowledged. Porapakarm thanks Swinburn Samuel Leyton for his excellent research assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

APPENDIX A: ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND OF THAI SOCIAL SECURITY SCHEME

In Thailand, there are several welfare and public program for formal workers which are lumped together under the social security scheme and receives funding from the contributions of employees, employers, and the government. Table A1 reports how the contributions are allocated. We explicitly incorporate only the contribution for the 2-benefit type (old-age pension and child allowance) in our studies.

| Employee (%) | Employer (%) | Government (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment benefits | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.25 |

| 4-benefit type (health, maternity, disability, and death) | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| 2-benefit type (old-age pension and child allowance) | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Total | 5 | 5 | 2.75 |

APPENDIX B: SUPPLEMENTARY FOR THE MODEL CALIBRATION

B1. Labor productivity

Figure B1 below plots the age-dependent wage profile  for each education and sector which is estimated from the LFS (2016–2019) while Figure B2 compares the variance of wage shock

for each education and sector which is estimated from the LFS (2016–2019) while Figure B2 compares the variance of wage shock  from our estimated wage shock process and the corresponding residual from the wage regression as explained in Section 4.2.4.

from our estimated wage shock process and the corresponding residual from the wage regression as explained in Section 4.2.4.

.

.

In the following, we report the discretized 3-state Markov process of the wage shock process  as described in Section 4.2.4.

as described in Section 4.2.4.

B2. Summary of model parameters

See Table B1.

| Parameters | Values | Sources/comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Survival probabilities |  |

See Section 4.1 | United Nations |

| Retirement age |  |

See Table 1 | |

| SS eligible age |  |

See Table 1 | |

| Maximum age |  |

99 | |

| Preferences | |||

| Discount factor (annual) |  |

See Section 4.3 | Target average net worth age 25-54 |

| Taste parameter of consumption |  |

See Section 4.3 | Target average working hours |

| Deterministic age earnings profile |  |

See Section 4.2.4 | |

| Wage shock process |  |

See Section 4.2.4 | Labor Force Survey (LFS) |

| Government | |||

| Progressive income tax |  |

|

Revenue department |

| Old-age allowance (THB per month) |  |

See Table 2 | Actual rate |

| Government spending (% GDP) |  |

15.90% | Balance the government budget in 2000 |

| Consumption tax |  |

7% | Actual rate |

| Government contribution to SSF |  |

1%a | Actual rate |

| Other sources of revenue |  |

9% of GDP | Average value during 2000-2020 |

| Social security | |||

| Transition probabilities (exit formal) |  |

See Section 4.2.2 | SS administrative data and LFS |

| Social security benefits |  |

See Section 3.1.3 | Actual SS formula |

| SS contribution rate |  |

3% | Actual rate |

| Maximum taxable earnings (per month) |  |

15,000 | Actual rate |

| Price variables | |||

| Return on savings (annual) |  |

4% | |

| Return on SS fund (annual) |  |

2.24% | Average real returns on SSF investmentb |

| Return on government debt (annual) |  |

0.9% | Average real 10-year government bond yieldc |

| growth rate of labor productivity |  |

3.2% | Average growth rate of GDP per capita (2010–2019) |

| Poverty line | 1627 THB | NESDC value of 2000–2004 | |

- a 1% of SS taxable earnings.

- b The real return on SSF is the average historical return between 2016 and 2020 which equals 3.61% per year, subtracted by the 10-year average rate of inflation 1.36%.

- c Average real 10-year government bond yield 2015–2020 is 2.26%.

APPENDIX C: SOCIAL SECURITY FUND: MODEL AND DATA (2000–2015)

To evaluate our model performance in terms of its financing projection of the SS program, Table C1 compares our projected SS fund balance (after converted into nominal values) with the available historical data. Note that the model assumes the SS fund started with zero balance in 2005. As described in Section 2.2, the social security scheme started collecting contributions in 1998 before expanding its coverage to all registered firms in 2002. If we were to assume an actual 2005 balance of 273,730 million THB, the model's SS fund balance in 2015 would be 1.18 trillion THB, which is close to the actual SS fund balance (1.28 trillion THB).

| Year | Actual | Model |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 57,530 |  |

| 2005 | 273,730 | 0 |

| 2010 | 653,139 | 483,744 |

| 2015 | 1,280,147 | 904,811 |

REFERENCES

- 1 This is due to a lack of enforcement and asymmetric information. For example, in Thailand, a single person with an annual income less than 120,000 THB is exempt from tax filing. Since the earnings of many self-employed or small businesses cannot be verifiable by the government, a large fraction of workers can avoid reporting their earnings.

- 2 See https://lis.parliament.go.th for details of each bill.

- 3 There is also an effort to introduce voluntary retirement savings programs for Thai informal workers and participants receive a government subsidy. Even though the program was introduced around the same time as the SS program for formal workers, its participation rate is very low.

- 4 Using the average exchange rate during 2000–2007, this is equivalent to 85 USD a month.

- 5 See data.worldbank.org.

- 6 See Ratanabanchuen (2019) for details of government workers’ pension scheme.

- 7 The SS Act initially required employers in nonagricultural sectors with 20 or more employees to register. After its expansion in 1993, employers with 10 or more employees must join, and it subsequently expanded to employers with at least one employee in 2002.

- 8 In reality, these contributions are also spent on the child allowance benefits. However, this is a small part of the fund. Therefore, we assume that the contributions go into the old-age public pension fund.

- 9 For an alternative assumption where there exists an actuarially fair one-period annuity market, see Storesletten et al. (2004).

- 10 We assume 16 available hours per day.

- 11 We abstract from the payroll taxes for unemployment and other benefits in Table A1.

- 12 In practice, we need to keep track of

only among SS participants whose contributing years is no more than 15 years (

only among SS participants whose contributing years is no more than 15 years ( ) since

) since  does not affect the annuity benefits.

does not affect the annuity benefits. - 13 As of 2015, around 72% of eligible people takes the OAA benefits. We abstract from modeling a (one-time) fixed cost to participate in the program. It is likely that the application and benefit transfer processes will be easier in the future, and participation will increase.