How much and how long? The transmission of external shocks on stock market in Chinese hospitality and tourism industry

Abstract

In this study, we employ the synthetic control method to evaluate the transmission of external shocks, taking COVID-19 as an example, on the stock market in the Chinese hospitality and tourism industry, specifically in the catering, hotel, cultural landscape, natural landscape, and travel agency sectors. We find an increasingly negative causal effect on stock returns in all five sectors within 1–2 days after the external shock occurred. However, this impact then gradually shrank, disappearing after 7 days. We also show that the short- and long-term causal effects of the external shock on stock volatility in the above sectors are positive and significant, due to the great uncertainty induced by the pandemic. We examine the sensitivity of stock market reactions and find that hotels are the most vulnerable among the five sectors in terms of the duration of the pandemic's negative impact. Finally, we report that larger firms in the catering and hotel sectors (compared to the other three sectors) show a greater increase in volatility. These findings provide valuable insights into financial market reactions to an external shock and offer implications for crisis management in the hospitality and tourism industry during such events.

1 INTRODUCTION

The catastrophic economic and social impact of an unforeseen external shock such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, usually raises widespread public concern and comes to the forefront of academic discussion. According to the World Bank, the global economy will experience the deepest downturn since World War II because of the pandemic, contracting by 5.2% in 2020 alone (The World Bank, 2020). Additionally, mental health problems such as anxiety, fear, and depression have been observed among the public, which may negatively affect market sentiment and social trust (Cao et al., 2020; Torales et al., 2020). Investors' crippling fear of a recession has led to a stock market crash regarded as the most devastating since the Wall Street Crash of 1929, with a plunge in the S&P 500 index of approximately 34% in the first quarter of 2020 (Ding et al., 2021). Meanwhile, high levels of economic uncertainty have led to a substantial increase in market volatility (Baker et al., 2020a; Zhang, Ouyang, et al., 2020).

Among the numerous industries exposed to risks from an external shock such as COVID-19, the hospitality industry is particularly vulnerable (Nicola et al., 2020), as travel usually relies on individuals' dispensable income and prearranged itineraries. With the implementation of global travel restrictions and social distancing measures, many scheduled trips have been disrupted, triggering a severe recession in the hospitality industry (Hao et al., 2020). In addition, growing safety concerns have made people reluctant to spend money on traveling and eating out, even in societies where the disease has been brought under control. A survey conducted by the National Restaurant Association suggests that about 70% of restaurant operators have laid off employees and reduced their operating hours, while nearly half of all restaurants have permanently or temporarily closed as the COVID-19 pandemic rages throughout the world (National Restaurant Association, 2020). Global data from the World Travel & Tourism Council (World Travel & Tourism Council, 2020) indicate that as of April 28, 2020, approximately 100.8 million jobs in tourism had been lost due to COVID-19. The overall economic impact of such a pandemic on the industry is almost five times greater than that of the 2008 global financial crisis, with a decline of approximately 30% in travel and tourism GDP relative to 2019 (World Travel & Tourism Council, 2020). This paper explores the devastating impact of COVID-19 on the hospitality and tourism industry by examining stock market reactions.

Although some studies explore the overall impact of such external shock on stock markets (Baker et al., 2020b; Liu et al., 2020; Wagner & Ramelli, 2020), the specific impact of the pandemic on stocks in the hospitality and tourism industry remains unknown. Research on the impact of the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak on Taiwanese hotel stock performance suggests that the abnormal returns of Taiwanese hotel stocks were significantly negatively affected by the outbreak of SARS (Chen, Jang, et al., 2007, Chen, 2007; Chen, 2011). Given the gap in the literature, this study provides a good foundation for further understanding of the following questions. First, what are the stock market reactions to an external shock such as a public health crisis, particularly across different sectors of the Chinese hospitality and tourism industry? Second, how do stock returns and volatility in this industry react differently to such crises in the short term and long term? Third, does firm size matter in this process? By exploring these questions, we can better understand the stock market reaction to an external shock closely related to consumers' travel needs and keep an eye on changes in investor sentiment in response to the crisis. This study also provides valuable insights into the relative vulnerability and resilience of different hospitality and tourism sectors, which will assist businesses on their respective paths to recovery.

To address the above questions and gain further understanding of the transmission of the external shock on stocks in the Chinese hospitality and tourism industry, we are the first to apply the Synthetic control method (SCM) to explore stock market reactions in representative sectors, specifically the catering, hotel, cultural landscape, natural landscape, and travel agency sectors. We compare the dynamic treatment effects and consider the impact of firm size on the reactions. We find that in each sector, the pandemic had an increasingly negative effect on stock returns within 1–2 days after the city of Wuhan was locked down on January 23, 2020 (hereafter referred to as the lockdown day). However, this negative effect gradually faded away over the long term. Regarding stock volatility, the short-term (first 7 days following the lockdown day) and long-term effects (beyond 7 days after the lockdown day) of the pandemic are all significant and positive. Next, we find that the hotel sector is the most vulnerable of the five sectors under study, in terms of enduring the longest-lasting negative shock. Last, we find an interesting relationship between firm size and stock market reactions: larger firms in the catering and hotel sectors (vs. the other three sectors) show increased stock volatility.

This study makes several contributions to the literature. First, among studies of stock market reactions to the unprecedented external shock, ours is the first to quantitatively examine these causal impacts in the Chinese hospitality and tourism industry by applying the SCM. Our study thus enriches the literature and contributes to the application of empirical research in this field. Second, this study compares stock market reactions in the short term and long term, and considers the sensitivity of reactions in different sectors, thus filling another gap in the literature. Third, this study enhances our understanding of the characteristics of companies most affected during the unanticipated crisis by revealing a positive relationship between firm size and increased stock volatility in the catering and hotel sectors.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Overall, this paper sheds light on the transmission of the COVID-19 pandemic on stock market in the Chinese hospitality and tourism industry. Studies on the impacts of infectious diseases on the hospitality and tourism industry and stock market serve as valuable references for our research. In addition, previous studies using the SCM offer guidance for the methodology of this study.

2.1 Impact of COVID-19 on the hospitality and tourism industry

Several studies focus on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the hospitality industry, and generally conclude that the crisis has had devastating effects on relevant sectors, exceeding those of previous crises, such as SARS in 2002 and the avian influenza in 2009 (Gössling et al., 2020; Gursoy & Chi, 2020). Compared with these infectious diseases that have threatened human health, COVID-19 is less lethal; however, this also means that numerous asymptomatic carriers can spread the virus before measures such as social distancing and mobility restrictions are taken (Bai et al., 2020; Gössling et al., 2020). In this context, sectors such as restaurants, hotels, and airlines are bound to suffer particular hardship (Nicola et al., 2020). Specifically, most restaurants have been negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has massively reduced the number of sit-in guests (Dube et al., 2021; Baker et al., 2020). Meanwhile, due to travel bans and stay-at-home orders, there has been a sharp decline in hotel occupancy and revenue (Gursoy & Chi, 2020; Nicola et al., 2020). Airlines have faced similarly great losses due to the suspension of international flights and reduced demand for domestic air travel (Hao et al., 2020). According to McKinsey & Company (2020), the decline in U.S. airline capacity caused by COVID-19 is between 7 and 17 times larger than that caused by the global financial crisis of 2008.

As the first country affected by the crisis, China has inevitably suffered greater losses than other countries (Hao et al., 2020). Since the Chinese government first implemented travel restrictions and lockdown policies on the initial breakout day, people have been reluctant to travel, resulting in a sharp decline in the number of airline passengers. Meanwhile, a series of travel bans has been imposed all over the world to suspend international flights and restrict the entry of travelers from infected areas, further increasing the number of flight cancelations (USA Today, 2020). Along with the crisis in aviation, catering and other hospitality sectors have fallen into a deep recession. For example, the hotel occupancy rate in China decreased by 89% between the beginning of 2020 and mid-January and remained at around 10% until the end of February (Hospitality Net, 2020). Unquestionably, given the damage caused by COVID-19, such as grounded flights and the shutting down of restaurants, hotels, and parks, the hospitality and tourism industry will take some time to regain its prosperity (Zenker & Kock, 2020).

In brief, the reasons why the hospitality and tourism industry is among the hardest hit are both objective and subjective. The objective factors are the restrictive measures implemented by governments around the world to increase social distancing and prevent unnecessary person-to-person contact (Anderson et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020). These policies have significantly decreased demand for hospitality services, resulting in the temporary or permanent shutdowns of some hotels and restaurants (Gursoy & Chi, 2020; Hao et al., 2020). The subjective factors that make the hospitality and tourism industry particularly vulnerable include consumers' concerns about safety and economic uncertainty, which are hindering the industry's recovery. Prior studies show that perceived safety risks can influence decision-making and that tourists prefer to visit places not subject to safety hazards (Enz, 2009; Kozak et al., 2007). Due to the safety concerns and economic uncertainty associated with COVID-19, people will likely be reluctant to spend money on travel for some time.

2.2 Impact of COVID-19 on stock market performance

As a contagious disease affecting almost all countries worldwide, COVID-19 has severely damaged stock market performance. In the U.S., the Dow Jones Industrial Average, S&P 500, and NASDAQ Composite Index fell dramatically after the outbreak of COVID-19, bottoming out on about March 23. In Asia, the Shanghai Composite Index, Hang Seng Index, and NIKKEI 225 Index were similarly affected (MarketWatch, 2020). Feverish fluctuations in the stock market caused panic among investors, and pessimistic investor sentiment, as both a mediator and a transmission channel, triggered a stock market crash, forming a vicious circle (Liu et al., 2020). Ashraf (2020) examines stock market reactions to the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and suggests that stock returns responded negatively to the increased number of confirmed cases from January 22, 2020 to April 17, 2020 in 64 countries. Consistent with Ashraf, (2020) argument, Al-Awadhi et al. (2020) indicate that both the daily growth in total confirmed cases and the number of fatalities caused by COVID-19 negatively affect stock returns across all companies. Despite the overall economic recession, however, stocks with higher environmental and social ratings generally show better performance, manifested as higher returns and lower volatility, during the crash (Albuquerque et al., 2020). Focusing on the U.S. restaurant industry, Song et al. (2020) examine how pre-pandemic firm characteristics moderate the effects of COVID-19 on stock returns, and report that larger firms with more leverage and greater cash flow are less vulnerable to the negative effects of the pandemic.

Regarding short-term and long-term stock market reactions, researchers hold various viewpoints. Using an event study method and focusing on Chinese and other Asian stock markets, Liu et al. (2020) report a significant short-term negative impact on the transportation, lodging and catering sectors, given the continuous and enormous decline in the cumulative abnormal returns in the 10 trading days following the outbreak. Zhang, Hu, et al. (2020) argue that the long-term impact of COVID-19 may take the form of mass unemployment and business failures in certain industries and sectors, such as tourism and aviation. A more optimistic view holds that despite market volatility in the short term, global stock markets still have the potential to bounce back in the long run (Outlook Money, 2020).

2.3 The synthetic control method

Developed by Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003), the SCM is widely used in comparative case studies to examine the causal effect of a specific event or policy intervention (Abadie et al., 2010). Using traditional empirical methods, it is generally difficult to assess the economic effects of a shock, such as an act of terrorism, due to a lack of knowledge of how the economic outcomes would have evolved in the absence of the shock (Abadie & Gardeazabal, 2003). The SCM makes up for the deficiency of traditional empirical methods by providing an effective means of examining the impact of an intervention. Using several potential comparison units, this method precisely estimates treatment effects by constructing a synthetic treated group to represent the counterfactual situation in which the treated group did not receive the treatment (Kreif et al., 2016). In comparative case studies, the selection of comparison units is crucial, as this directly affects the correctness of the conclusions. Instead of using a single comparison unit, the SCM selects a weighted average of all potential comparison units that best resemble the characteristics of the treatment group. This is deemed an outstanding advantage of the SCM method (Abadie et al., 2015).

Prior studies apply the SCM to the impacts of unexpected events and government policies. For instance, Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003) use this method to investigate the economic costs of a conflict and find that per capita GDP in a region decreases by about 10% after a terrorist act relative to a synthetic control region in which this act of terrorism does not occur. In a later study, Kleven et al. (2013) use this method to analyze the effects of tax rates on the international migration of football players and demonstrate that a foreign-specific tax break can successfully attract foreign players. An even more recent study applies the SCM in the context of COVID-19 to analyze the effect of face masks on the spread of coronavirus in Germany and concludes that wearing face masks considerably prevents the Coronavirus infections and results in an approximately 40% reduction in the daily growth rate of confirmed cases (Mitze et al., 2020).

3 METHODOLOGY AND DATA

3.1 Methodology

To evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the stocks of the hospitality and tourism industry in China, we need to compare the outcomes of units exposed to this shock with those in the absence of this shock. However, due to the global spread of COVID-19, it is difficult to find an effective real-life sample not affected by the disease to serve as a control group. Inspired by Abadie et al. (2010) and Hsiao et al. (2012), we apply a panel data method to construct a synthetic control group that does not experience the shock, enabling us to perform counterfactual analysis. This method allows us to precisely estimate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by comparing the counterfactual outcomes in the absence of the shock with the observed outcomes under the shock.

The main steps in our research proceed as follows. First, based on the Standard Industrial Classification, we select five representative sectors of the hospitality and tourism industry, namely the catering, hotel, cultural landscape, natural landscape, and travel agency sectors, using a weighted average of total market value. Here, the cultural landscape refers to the tourist attraction intentionally designed and created by humans, such as parks and zoos. Contrary to this, the natural landscape is the original landscape that exists in nature and is not apparently affected by human activity, such as mountains and ocean. Second, using the SCM, we create a synthetic control group using the stock index of the corresponding sector (referred to interchangeably as the sector index or stock index by sector) from previous years. After that, we obtain the treatment effects by calculating the differences between the returns of the real index and the predicted returns of the synthetic one. Next, we employ a difference-in-differences (DD) method to evaluate the short-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a parametric method, the DD approach allows us to obtain point estimates and interval estimates with ease.

3.2 Data

We obtain Chinese stock market data, including yearly market value, daily returns, and daily volatility, from the RESSET database, a professional platform that provides reliable financial data for researchers and is widely used in recent empirical studies (Broadstock et al., 2012; Yang & Zhang, 2014). On January 23, 2020, the strictest lockdown measures were implemented in Wuhan, the city where the pandemic broke out. As the first public health intervention implemented by the Chinese government, the Wuhan lockdown raised public awareness of the severity of the pandemic. Meanwhile, strict travel restrictions negatively affected the Chinese hospitality and tourism industry. Therefore, we take January 23, 2020, the date that the Wuhan lockdown began, as the beginning of this shock. This date is hereafter referred to as the lockdown day. Our initial sample covers all stocks in the hospitality and tourism industry, totaling 35, that are listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange. After removing two stocks under special treatment, we obtained 33 stocks in the five representative sectors listed above. Table A1 lists the individual stocks by each of the five sectors.

As the whole stock market has been exposed to the shock since early 2020, it is difficult to find any unaffected stocks to serve as controls. Therefore, we turn to the performance of the selected stocks in previous years, before the pandemic occurred. Recall that the SCM allows us to construct a synthetic group by choosing appropriate weights. Here, therefore, the synthetic group represents the treatment group in the absence of COVID-19. In this paper, our donor pool includes data on the selected stocks in 2017, 2018, and 2019, while the treatment group comprises stocks from December 2019 to March 2020. To optimize our synthetic group, we take a 3-day moving average of daily returns and gather the daily stock volatility, calculated using a 20-day moving average.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Impact of COVID-19 on stock return and volatility

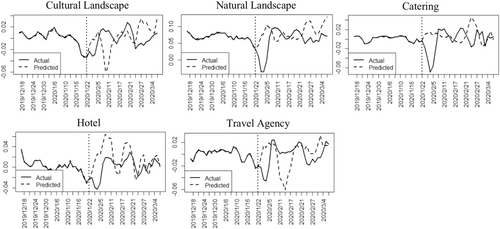

As explained above, we evaluated the impacts of COVID-19 on different sectors by averaging all individual stocks within each sector (catering, hotels, cultural landscape, natural landscape, and travel agencies), weighted by market value, to create a sector-specific index. We then applied the SCM to assess the impact on each sector. The results are displayed below.

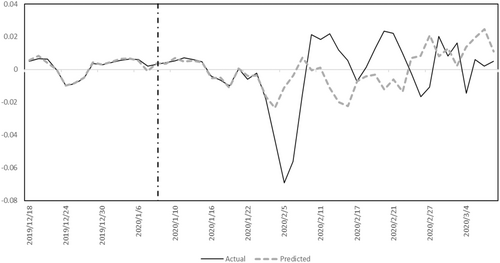

Figure 1 displays the returns of the stock index for each real sector and its synthetic counterpart between December 18, 2019, and March 4, 2020. On January 23, 2020, the central government of China imposed a lockdown in Wuhan and other cities in Hubei province, so we take this date as the beginning of the shock. We observe that for each sector, the trend of the synthetic sector index returns closely aligns with the trend of the actual sector index before the lockdown day, with an R-squared value higher than 0.98. This suggests that each synthetic sector index provides a precise estimate of its corresponding return in the absence of COVID-19, indicating the validity of the SCM.

The estimated effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on stock returns is the difference between actual returns and predicted returns after the date on which Wuhan was locked down. As shown in Figure 1, we observe that immediately after the lockdown day, the actual stock returns decreased noticeably, especially for the natural landscape, catering, hotel, and travel agency sectors, while the predicted stock returns showed obvious upward trends. This indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic has a short-term negative effect on stock returns in the Chinese hospitality and tourism industry. In addition, we observe that after their sharp decline, the actual stock returns of these sectors rapidly bounced back. Therefore, the long-term effect of the COVID-19 pandemic seems to be smaller than the short-term effect. Figure 1 also shows that the cultural landscape sector is less vulnerable to the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic than the other sectors, with a smaller decline in its actual stock return. As of early March 2020, we see a positive jump in stock returns following the plunge caused by the Wuhan lockdown. Baker et al. (2020b) attribute this to the guiding roles of policy and news. This explanation makes sense based on the reality in China. Since February 28, the daily number of cured cases has outnumbered that of confirmed new cases in China, and the number of persons under medical observation has substantially decreased, indicating that the pandemic has been brought under initial control. This has conveyed positive signals to the public, probably relieving investors' anxiety and fear and encouraging the recovery of the stock market. The weights used to form the synthetic group of return and volatility for each sector, reflecting the contributions from each of the three prior years, are shown in Tables A2 and A3, respectively.

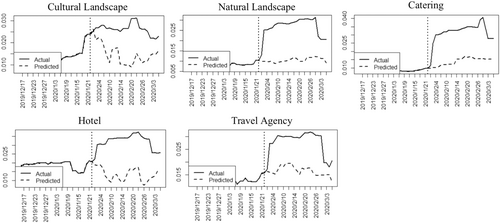

Figure 2 displays the actual stock volatility and its synthetic counterpart from December 17, 2019 to March 5, 2020. Similar to the results above, there is no difference between the actual volatility and the synthetic volatility for each sector before Wuhan lockdown, which indicates that the synthetic stock index closely resembles the actual stock index in each case. However, immediately after the lockdown day, we observe a sharp increase in actual volatility compared with the relatively moderate trend of synthetic volatility. Meanwhile, the overall volatility of the actual stock index consistently exceeds that of the synthetic indices after the lockdown day. This trend persists even into early March, when the pandemic was under control, indicating that the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened stock volatility in both the short term and long term.

4.2 Sensitivity of responses to the COVID-19 pandemic

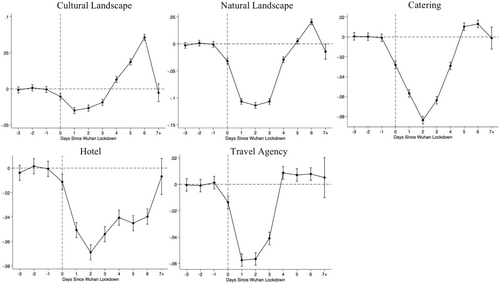

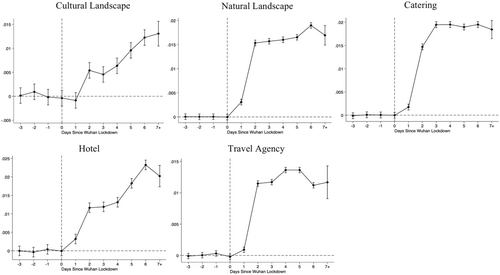

As explained above, the estimated effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sector performance of the hospitality and tourism industry are the differences between the returns and volatility of the actual stock indices and their synthetic counterparts after the pandemic. Therefore, to quantify the treatment effects, test their levels of significance, and precisely evaluate the sensitivity of stock response, particularly in short term, we conduct a DD analysis, using each individual stock as the unit of analysis. The results are presented in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3 displays the dynamic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on stock returns across different sectors. We observe that before the Wuhan lockdown, the daily treatment effects are around 0 and insignificant, confirming that a parallel pre-trend exists between the treatment group and control group. This assumption is a key criterion for the validity of the DD method. From the date on which Wuhan was first locked down, we choose the next 7 consecutive days as an event window to examine short-term stock market reactions. This approach is consistent with the literature (Walker et al., 2005). It reveals that on the day of the event, the stock return of each sector suffered a significant decline, which was even greater on the following day. However, we also observe that the duration of this reduction varied among the five sectors, implying that their market reactions have different degrees of sensitivity. Compared with the other four sectors, whose returns decreased in the 3 or 4 days after Wuhan's lockdown and then increased again, becoming positive, the hotel sector experienced a longer-lasting decline in returns. This suggests that the hotel sector is the most vulnerable to the shock of COVID-19 in terms of stock returns. Figure 3 also shows that after the first week following the event, the gap between real return and predicted return converges to 0 for each sector, suggesting that the long-term effect of COVID-19 on stock return is insignificant.

Figure 4 plots the dynamic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on stock volatility across the five sectors we examined. Notably, for the first 7 days following the Wuhan lockdown, real stock volatility is consistently higher than the predicted volatility of the synthetic stocks, with high levels of significance. Furthermore, we observe the sharpest increase in the treatment effects on the second day after the event rather than the day of the event, indicating that a lag exists between the external shock and stock market reactions. However, in contrast to the insignificant long-term effects of COVID-19 on stock returns, the positive effects of this shock on market volatility are ongoing and significant. According to prior studies, the perceived risk of disasters leads to high market volatility in the long term (Berkman et al., 2011; Wachter, 2013). Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic has generated widespread concern about a crisis-prone and highly uncertain future, which may be responsible for the continued increase in market volatility.

Table 1 presents the estimated daily treatment effects on stock return and volatility in the first week following the Wuhan lockdown. On average, the five hospitality and tourism sectors under study experienced a decline in their returns of 0.019 on the day of the event and 0.060 on the following day. Note that the decline in the stock return of the natural landscape sector is much greater than that of the other four sectors, which indicates that the natural landscape sector is the most severely affected in terms of the magnitude of impact. In China, the natural landscape sector was particularly hard hit by the strict lockdown policies, including extensive domestic and intercity quarantine measures. These restrictions drastically reduced the flow of tourists to natural attractions, which are heavily dependent on visitor attendance. As a result, revenues from ticket sales and related tourism services plummeted, leading to a more significant negative impact on stock returns in this sector. In contrast, the hotel sector, although severely impacted, did not suffer as much in magnitude as the natural landscape sector. While global lockdowns and travel restrictions led to a sharp decline in leisure and travel-related activities, some hotels were able to maintain occupancy through business travelers and by being designated as government-regulated quarantine destinations. Similarly, in the catering sector, while there was a significant reduction in dine-in services, a notable increase in food delivery services was observed. Our finding that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on different subsectors of tourism varies significantly across different episodes is consistent with Abdelsalam et al. (2023).

| Return | Volatility | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Cultural landscape | (2) Natural landscape | (3) Catering | (4) Hotel | (5) Travel agency | (6) Cultural landscape | (7) Natural landscape | (8) Catering | (9) Hotel | (10) Travel agency | |

| Day 0 | −0.011 | −0.032 | −0.028*** | −0.011*** | −0.014*** | −3.80E-4 | −2.19E-5 | −2.42E-5 | −5.47E-5 | −2.03E-4 |

| Day 1 | −0.030*** | −0.107*** | −0.057 | −0.051*** | −0.057 | −8.64E-4 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003*** | 9.06E-4*** |

| Day 2 | −0.027 | −0.114*** | −0.084*** | −0.069*** | −0.057*** | 0.005*** | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.012*** | 0.011 |

| Day 3 | −0.019 | −0.107*** | −0.064 | −0.054 | −0.041*** | 0.005*** | 0.016*** | 0.019*** | 0.012 | 0.012*** |

| Day 4 | 0.013*** | −0.029*** | −0.029*** | −0.040 | 0.009*** | 0.006*** | 0.016 | 0.020*** | 0.013*** | 0.014 |

| Day 5 | 0.037 | 0.005 | 0.010*** | −0.045*** | 0.007*** | 0.010*** | 0.017 | 0.019*** | 0.018*** | 0.014 |

| Day 6 | 0.071*** | 0.041*** | 0.013 | −0.040*** | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.019 | 0.020*** | 0.023 | 0.011 |

- Note: ***, **, and * denote significance levels at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively.

It is also obvious from Table 1 that the daily effects on the returns of the hotel sector are continuously negative, while the effects on the other four sectors become positive on Day 4 or Day 5. This suggests that in terms of the duration of negative impact, the hotel sector is the most vulnerable to COVID-19, which is consistent with the findings illustrated in Figure 3. The treatment effect on stock volatility of the hotel sector tends to fluctuate around 0.012, with a maximum of 0.023 reached on day 6. The prolonged negative effect of the hotel sector may be due to its operational structure, which includes high operating costs such as maintenance, staffing, and utilities that persist regardless of occupancy levels. This prolonged financial strain, even after restrictions were lifted, resulted in a slower recovery of occupancy rates and revenues to pre-pandemic levels. While some hospitality businesses demonstrated greater risk preparedness, with better profitability and financial liquidity, the prolonged consequences of the pandemic may erode these advantages, particularly as cash inflows diminish and financial slack resources deplete (Wieczorek-Kosmala, 2021).

Finally, the varied impact across sectors can be attributed to differences in customer base, business models, fixed costs and operational flexibility. These distinctions provide valuable avenues for future research.

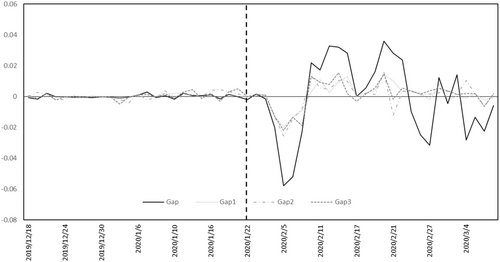

4.3 Placebo tests

To test the validity of the causal interpretation of our results, we conducted two placebo tests. First, we performed a placebo test by selecting a different, unaffected stock index from the donor pool as a fictitious treated group and reapplying the SCM. As an example, Figure 5 shows the placebo test based on the return of the catering sector. The gap represents the baseline effect. Gap 1, Gap 2, and Gap 3 are the pseudo effects using one index of the donor pool as the fictitious treated group. The results indicated that all pseudo effects were smaller than the baseline effect in magnitude. Second, we randomly assigned the timing of COVID-19 to a period preceding the actual occurrence. The results suggest no significant impact, as shown in Figure 6. These placebo tests confirm that the observed effects are not driven by pre-existing trends or other confounding factors.

4.4 Small versus large enterprises: Which are more vulnerable?

Table 2 presents the impact of firm size on the treatment effects of COVID-19 on stock return and volatility. Columns (1) and (2) show the results of the single-factor models. The dependent variables are the treatment effects, which are estimated in the previous sections by calculating the differences between the returns and volatility of the real stocks and the synthetic stocks using the DD method. The independent variable is firm size, which is measured by the log of total assets, following prior studies (Song et al., 2020). In column (1), for all sectors, the coefficients of firm size are insignificant, indicating that there are no significant differences in the treatment effects across firms of different sizes in terms of stock returns. However, in column (2), we observe that for the catering and hotel sectors, the coefficients are positive and significant, while for the natural landscape and travel agency sectors, they are negative and significant. Thus, it is not surprising that the total effect is insignificant when we consider all five sectors. The inconsistent results are interesting and might reveal the different relationships between firm size and the treatment effects of COVID-19 on stock volatility in different sectors. This finding suggests that large enterprises in the catering and hotel sectors have experienced a greater increase in volatility due to COVID-19 than those in the natural landscape and travel agency sectors. A possible explanation for these findings lies in media attention. Manela and Moreira (2017) hold that news coverage can, to some extent, influence the disaster risk perceived by investors. In the catering and hotel sectors, which are key areas of investment in China, large enterprises generally obtain more media attention than their small counterparts. Mixed media coverage leads to rising concerns and uncertainty about their survival during the pandemic, thus boosting their stock volatility. In other sectors, investors tend to focus less on large enterprises, as these companies are expected to have the capacity to withstand the crisis, resulting in reduced stock volatility.

| (1) Return | (2) Volatility | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Coefficient | 1.407E-4 | 1.13E-5 |

| p-Value | 0.856 | 0.964 | |

| Catering | Coefficient | −0.009 | 0.028 |

| p-Value | 0.498 | 0.000 | |

| Hotel | coefficient | 9.93E-4 | 6.37E-4*** |

| p-Value | 0.252 | 0.003 | |

| Cultural landscape | Coefficient | −0.002 | −0.001 |

| p-Value | 0.637 | 0.355 | |

| Natural landscape | Coefficient | −0.002 | −0.004*** |

| p-Value | 0.516 | 0.009 | |

| Travel agency | Coefficient | −8.29E-4 | −0.002** |

| p-Value | 0.690 | 0.044 |

- Note: ***, **, and * denote significance levels at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Using the SCM, this paper first discusses the short-term and long-term transmission of the COVID-19 pandemic on stock returns and volatility in the Chinese hospitality and tourism industry. The empirical results show that in the first 3 days after the Wuhan lockdown, the stock returns of firms belonging to Chinese hospitality and tourism industry experienced a dramatic plunge, swiftly followed by a rebound from the bottom. This suggests that the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on stock returns are insignificant. As explained by Liu et al. (2020), investors' pessimistic sentiment is the primary factor responsible for the short-term decline in stock returns. Government restrictions on traveling and commercial activity have also exerted an enormous negative effect on the service industries, which is the main reason why the stock market has reacted to COVID-19 much more severely than it did to previous epidemics (Baker et al., 2020b).

We also find that the COVID-19 shock has given rise to a long-term increase in stock volatility in the hospitality and tourism industry. High stock volatility translates into great uncertainty in the financial market. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, market sentiment is unstable, and its instability is amplified through social media, which may well cause extreme price movements and boost stock volatility (Zhang, Hu, et al., 2020).

To examine the sensitivity of different sectors to this shock, we further conduct a DD analysis to quantitatively evaluate the treatment effects of the COVID-19 pandemic for the five representative sectors. The empirical results show that hotels are the most vulnerable sector in terms of the duration of the pandemic's negative impact and that recovery will be particularly challenging for this sector. To address these challenges, policy interventions could include extending financial support programs, incentivizing enhanced risk management strategies, providing liquidity assistance, and implementing initiatives to stimulate occupancy rates, thereby supporting the industry's recovery and long-term resilience. Meanwhile, hotel managers must develop appropriate strategies to cope with the ensuing economic crisis (Hao et al., 2020).

Finally, we use additional regressions to explore the relationship between the treatment effects and firm size. The empirical results show that for the catering and hotel sectors, firm size is positively correlated with the treatment effects on stock volatility. This means that larger hotels and restaurants have generally suffered a greater increase in stock volatility due to COVID-19. Surprisingly, however, this effect is not observed in the other three sectors. One possible explanation is that firm size is strongly related to default risk (Glennon & Nigro, 2005; Zhang, Hu, et al., 2020). However, other factors such as higher leverage, increased cash flows, lower ROA, and greater internationalization may also contribute to a firm's resilience against external disruptions, providing avenues for further research.

Furthermore, given the significant impact of external shocks on stock volatility, it is essential to enhance financial resilience strategies within the industry. There is an urgent need for designing systemic interventions aimed at alleviating liquidity tensions (Wieczorek-Kosmala, 2021). Meanwhile, encouraging firms to build financial buffers and invest in risk management practices can better prepare them to withstand future crises.

Our study provides inspiration and suggests directions for future research. First, this paper introduces the SCM method to the study of COVID-19. Most previous studies in this area use linear regressions or draw conclusions solely from existing data trends; they may thus ignore some potential endogenous factors. Our use of the SCM addresses this limitation by constructing counterfactuals and analyzing the pure treatment effects of the COVID-19 shock. Future research could also adopt the SCM method as an excellent tool for analysis of other issues relating to the impacts of external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, although we examine the impact of firm size on the treatment effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the transmission channel and influencing mechanism remain unaddressed and are worthy of further exploration. Third, this paper examines only stock market reactions during the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research should study stock market reactions in the post-pandemic era, as this will not only provide effective guidance for the recovery of the hospitality and tourism industry but also shed light on post-pandemic market sentiment and investor confidence.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yuan Chen: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; project administration; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Qikexin Yu: Software; validation; writing—review and editing. Peiwen yuan: Data curation; methodology; resources; software; writing—original draft. Yeyang Zhao: Software; validation; writing—review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This research involves no human subjects, animal experiments, or collection of personal data, and therefore does not require ethics committee approval.

APPENDIX

| Sectors | Individual stocks |

|---|---|

| Cultural landscape | 300144 (宋城演艺) 600088 (中视传媒) 600593 (大连圣亚) |

| Natural landscape | 000430 (张家界) 000888 (峨眉山) 000978 (桂林旅游) 600054 (黄山旅游) 600749 (西藏旅游) 603099 (长白山) 603136 (天目湖) 603199 (九华旅游) 900942 (黄山B股) |

| Catering | 000721 (西安饮食) 002186 (全聚德) |

| Hotel | 000428 (华天酒店) 000613 (大东海A) 200613 (东海B) 600258 (首旅酒店) 600754 (锦江酒店) 601007 (金陵饭店) 900934 (大锦江B股) |

| Travel agency | 000524 (岭南控股) 000610 (西安旅游) 000796 (凯撒旅业) 002033 (丽江股份) 002059 (云南旅游) 002159 (三特索道) 002707 (众信旅游) 300178 (腾邦国际) 600138 (中青旅) 600706 (曲江文旅) 601888 (中国中免) 900929 (锦旅B股) |

| Sectors | Weights | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2017 | Year 2018 | Year 2019 | |

| Cultural landscape | 0.155 | 0.232 | 0.613 |

| Natural landscape | 0.214 | 0.403 | 0.383 |

| Catering | 0.232 | 0.370 | 0.398 |

| Hotel | 0.214 | 0.472 | 0.314 |

| Travel agency | 0.221 | 0.590 | 0.189 |

| Sectors | Weights | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2017 | Year 2018 | Year 2019 | |

| Cultural landscape | 0.342 | 0.425 | 0.233 |

| Natural landscape | 0.242 | 0.339 | 0.419 |

| Catering | 0.366 | 0.272 | 0.362 |

| Hotel | 0.335 | 0.319 | 0.346 |

| Travel agency | 0.217 | 0.224 | 0.559 |