A Case of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis During Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma, Complicated by Pancytopenia Attributed to Cytomegalovirus Infection

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is characterized by macrophage and cytotoxic lymphocyte hyperactivation, fever, pancytopenia, liver dysfunction, and abnormal coagulation. However, no specific treatments have been established for HLH caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old male with clear cell renal carcinoma was treated with pembrolizumab and lenvatinib. Fifteen days later, he developed pancytopenia, liver and renal impairments, hypofibrinogenemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and elevated ferritin levels. Subsequently, he was admitted to the ICU for respiratory and circulatory instabilities. The patient was diagnosed with HLH and treated with high-dose corticosteroids and mycophenolate mofetil. Pancytopenia persisted and required massive blood transfusions. Cytomegalovirus infection was found to be the cause, and pancytopenia improved with ganciclovir. The patient was discharged from the ICU after 21 days.

Conclusion

We present the case of a patient who developed HLH as an immune-related adverse event along with a secondary cytomegalovirus infection, resulting in prolonged pancytopenia.

Summary

- HLH is one of the irAEs, but it is not yet well recognized and there is no established treatment for it.

- Furthermore, in this case, cytomegalovirus infection is associated with immunosuppressive therapies for irAE HLH.

- This is the first report of HLH caused by the IO-TKI combination therapy and complicated by pancytopenia caused by cytomegalovirus infection.

1 Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is characterized by the hyperactivation of macrophages and cytotoxic lymphocytes, resulting in progressive tissue injury and multiple organ failure [1]. HLH arises from immune dysregulation caused by genetic mutations, various infections, inflammation, and malignant triggers (mostly hematological) [2, 3]. The major clinical findings include fever, blood cell loss in two or more systems, elevated aminotransferase and ferritin levels, and coagulopathy. It is a rare but systemic syndrome and life-threatening disease [2].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) are widely used as antitumor treatments, but can cause adverse events by overactivating the immune system. HLH, as an immune-related adverse event (irAE), is still underreported and underrecognized [4]. According to the HLH-2004 chemoimmunotherapy, immunosuppressive therapies, including dexamethasone, etoposide, cyclosporine A, and methotrexate, are major treatment options for HLH [5], but no specific treatment regimens for HLH caused by ICI are available, and optimal treatment has not been established [6]. Further, attention should be paid to secondary infections caused by immunosuppressive therapies [7].

We report a patient who received pembrolizumab and lenvatinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, developed HLH, was treated with high-dose corticosteroids and mycophenolate mofetil, and developed pancytopenia because of cytomegalovirus infection.

2 Case Presentation

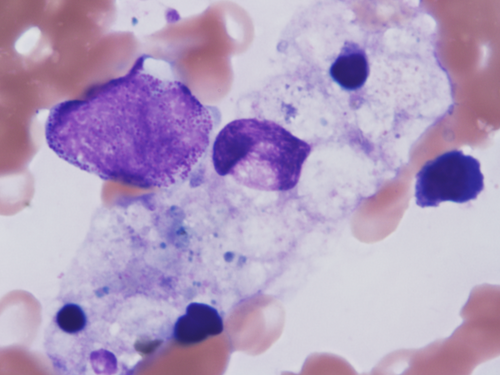

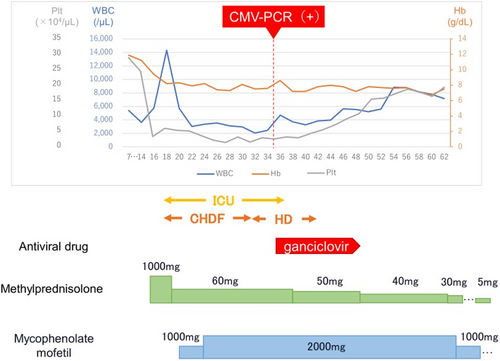

A 63-year-old male diagnosed with clear cell renal cell carcinoma with pulmonary and lymph node metastases (cT3bN2M1) was treated with pembrolizumab (200 mg) and lenvatinib (20 mg) based on IMDC risk factors (anemia, time from diagnosis to treatment < 1 year, and elevated corrected calcium) and a Karnofsky performance status of 100%. He was classified as having a poor International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) risk score. He had a medical history of hypertension, untreated diabetes mellitus, and smoking (Brinkman index, 880), but no allergies. Fifteen days after initiating pembrolizumab and lenvatinib, the patient showed no fever and stable hemodynamics. However, laboratory tests revealed anemia (hemoglobin level, 8.2 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (platelet level, 3.1 × 104 /μL), renal dysfunction (creatinine level, 2.6 mg/dL), liver dysfunction (transaminase level, 260 U/L), hypertriglyceridemia (triglycerides level, 373 mg/dL), elevated C-reactive protein (19.3 mg/dL), ferritin (167 656 ng/mL), creatinine kinase (1957 U/L), and D-dimer (319.8 μg/dL) (Table 1). Computed tomography showed no evidence of new thrombus formation or infection. Under consultation with the hematology, HLH was suspected. Despite the patient's low platelet count, a bone marrow biopsy was performed to rapidly differentiate it from other diseases that can cause pancytopenia, such as leukemia and aplastic anemia. Bone marrow biopsy revealed haemophagocytic phagocytosis by macrophages (Figure 1), leading to a diagnosis of HLH. High-dose corticosteroids (methylprednisolone, mPSL: 1, 000 mg/day) were initiated. However, 2 days later, the patient developed fever (38.6°C) and hypotension (systolic blood pressure 56 mmHg), and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). His renal function deteriorated (creatinine, 6.91 mg/dL), requiring continuous hemodiafiltration (CHDF). Methylprednisolone was tapered to 60 mg/day (1 mg/kg equivalent), and mycophenolate mofetil was initiated at 1000 mg/day and escalated to 2000 mg/day over 3 days. Liver function gradually improved with mycophenolate therapy. Although initial pancytopenia temporarily improved with corticosteroids and mycophenolate mofetil, it subsequently worsened and required daily blood transfusions. Due to the recurrence of pancytopenia, we initially considered a relapse of hemophagocytic syndrome and increased the dose of the immunosuppressant (mycophenolate mofetil instead of steroids due to elevated blood glucose levels). However, the response to treatment was poor, leading us to suspect a secondary factor other than hemophagocytic syndrome and prompting us to perform various viral tests. Further investigation revealed a positive cytomegalovirus PCR test result, indicating that secondary infection was the cause of prolonged myelosuppression. Ganciclovir initiation led to rapid improvement in myelosuppression; however, extensive transfusions (red blood cell concentrate, 22 units; platelet concentrate, 260 units) and frequent administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) were required because of delayed diagnosis. After 21 days in the ICU, the patient was discharged and able to discontinue dialysis. Systemic methylprednisolone was gradually tapered to 5 mg/day and mycophenolate was discontinued (Figure 2).

| Pre-administration | Day 15 | Pre-administration | Day 15 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | Blood chemistry | ||||||

| WBC | (×102/μL) | 70.2 | 28.2 | TP | (g/dL) | 8.2 | 5.5 |

| Neu | (%) | 74.3 | 68.5 | Alb | (g/dL) | 3.8 | 2.0 |

| Eos | (%) | 1.1 | 3.0 | AST | (U/L) | 14 | 260 |

| Bas | (%) | 0.3 | 0.0 | ALT | (U/L) | 9 | 91 |

| Lym | (%) | 19.5 | 16.0 | T-Bil | (mg/dL) | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Mono | (%) | 4.8 | 0.5 | LDH | (U/L) | 188 | 1979 |

| RBC | (×104/μL) | 387 | 325.0 | ALP | (U/L) | 96 | 207 |

| Hb | (g/dL) | 11.7 | 8.2 | ɤ-GTP | (U/L) | 100 | 163 |

| Plt | (×104/μL) | 28.8 | 3.1 | Cr | (mg/dL) | 1.23 | 2.6 |

| Na | (mmol/L) | 132 | 123 | ||||

| K | (mmol/L) | 4.6 | 4.1 | ||||

| Coagulation and fibrinolytic system | Cl | (mmol/L) | 99 | 96 | |||

| PT-INR | 1.08 | 1.50 | CRP | (mg/dL) | 2.67 | 19.3 | |

| Fibrinogen | (mg/dL) | 498 | 185 | TG | (mg/dL) | ー | 373 |

| FDP | (μg/mL) | 3.3 | 698.4 | Ferritin | (ng/mL) | ー | 167 665 |

| D-dimer | (μg/mL) | 1.1 | 319.8 | sIL-2R | (U/mL) | ー | 7389 |

Clinical course.CMV-PCR, cytomegalovirus PCR test; Plt: platelets; WBC, white blood cells; Hb, hemoglobin; ICU, intensive care unit; CHDF, continuous hemofiltration; HD, hemodialysis.

Cabozantinib treatment was sequentially initiated when the methylprednisolone dose reached 5 mg/day. Approximately 5 months after initiating cabozantinib treatment, the patient underwent cytoreductive nephrectomy while maintaining stable disease (RECIST version 1.1) on a CT scan. However, the patient's respiratory status deteriorated because of increased cancerous pleural effusion, leading to death approximately one and a half months post-surgery.

3 Discussion

HLH causes multi-organ dysfunction, pancytopenia, and coagulation disorders owing to excessive immune activation [5]. It is a fatal disease, requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment. However, HLH as an irAE is rare, with a limited number of reported cases.

Among the 3106 cases of HLH reported in VigiBase, which is the World Health Organization (WHO) international pharmacovigilance database, 177 (5.7%) were caused by ICI therapy. HLH was more frequently associated with nivolumab in monotherapy (21.3%), the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab (33.8%), and pembrolizumab (30.2%). All cases were serious, but 58.4% of patients recovered. However, 15.3% of the patients had a fatal course [4]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of HLH caused by the IO-TKI combination therapy.

Additionally, HLH symptoms can be similar to those of other conditions commonly observed in patients with cancer, such as acute liver dysfunction, sepsis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome, leading to delayed or overlooked diagnoses [8].

Our patient met the following diagnostic criteria outlined in the HLH-2004 guidelines: fever, myelosuppression, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, high ferritin levels, and hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow [9]. Although a bone marrow biopsy provides supportive evidence, it is not definitive for diagnosing HLH [10].

Treatment for HLH typically involves an HLH-2004 chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of dexamethasone, etoposide, cyclosporine A, and methotrexate [5]. However, owing to severe renal dysfunction, we did not choose cyclosporin A. Liver dysfunction worsened despite steroid use. We thus initiated treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, which is recommended for the steroid-resistant irAE hepatitis [7]. Although the lack of a liver biopsy precludes the confirmation of irAE hepatitis, liver function improved following mycophenolate mofetil initiation.

Vigilance against secondary infections through potent immunosuppressive therapies is paramount as they can be life-threatening [7]. In our case, although pancytopenia initially responded to steroid therapy, it worsened again because of a secondary cytomegalovirus infection. However, because of our assumption that pancytopenia was caused by the hemophagocytic syndrome, the diagnosis of the secondary infection causing another myelosuppression was delayed. The initiation of ganciclovir led to an improvement in pancytopenia, suggesting that the prolonged pancytopenia was caused by the concurrent cytomegalovirus infection; previous studies have also reported severe cases of pneumocystis pneumonia during treatment for irAEs [11].

However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing pancytopenia caused by cytomegalovirus infection associated with immunosuppressive therapies for irAE HLH.

Considering the use of high-dose corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs, treatment must be administered with a full awareness of the potential for secondary infections.

4 Conclusions

It is of paramount importance to acknowledge that HLH is a potential irAE that may manifest during ICI therapy. Early identification and prompt initiation of treatment based on clinical symptoms are essential for the effective management of HLH. Moreover, vigilant monitoring of opportunistic infections during immunosuppressive therapy for irAEs is imperative.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for giving us permission to publish this report.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Mikio Sugimoto is an Editorial Board member of International Journal of Urology and a co-author of this article. To minimize bias, he was excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication.