A successful case of urinary rediversion from a complicated cutaneous ureterostomy to a new ileal conduit

Abstract

Introduction

A ureteral stricture often develops after a cutaneous ureterostomy and can lead to complicated situations in some cases.

Case presentation

We performed surgery on a 54-year-old man who required routine replacement of a ureteral stent every 2 weeks after cystectomy. We surgically converted his cutaneous ureterostomy into a new ileal conduit. Following the surgery, his ureteral stent was removed, allowing him to resume his social activities.

Conclusion

We reported the possibility of urinary rediversion as a treatment option for a complicated cutaneous ureterostomy patient.

Abbreviations & Acronyms

-

- CT

-

- computed tomography

-

- CU

-

- cutaneous ureterostomy

-

- ICG

-

- indocyanine green

-

- PN

-

- percutaneous nephrostomy

-

- QoL

-

- quality of life

-

- US

-

- ureteral stent

-

- UTI

-

- urinary tract infection

Keynote message

We report a successful case of urinary rediversion from a complicated cutaneous ureterostomy to a new ileal conduit. For the number of potential patients, our report is rare and we believe it will be helpful to those concerned with similar cases.

Introduction

In certain patients, CU may result in ureteral stenosis, requiring US. Such patients need routine replacement of the US and prolonged hospital visits. Continuous replacement of the US results in complications such as pain and UTI. Furthermore, complications and frequent hospital visits can impair the patient's social activities and QoL. We report a case in which a patient who had undergone CU and developed ureteral stenosis was successfully treated by the creation of a new ileal conduit or “urinary rediversion,” resulting in improved QoL.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old man who has had diabetes mellitus for 10 years underwent open sigmoid colectomy and cystectomy due to bladder invasion of colon cancer, with a temporary ileostomy created on the left abdomen and a CU on the right. While the postoperative course after colon cancer was favorable, he developed ureteral strictures necessitating routine replacements of the US. Eventually, he required replacement of his US every 2 weeks due to frequent obstructions. At the 6th month after the surgery, his left US was dislodged accidentally and could not be replaced because we could not insert a new one. After this event, his serum creatinine concentration increased from 1.05 mg/dL to 2.04 mg/dL. Four months after the dislodgment of his left US, he presented at our hospital with abdominal pain and distention. CT revealed that the cause of the symptoms was a subcutaneous abscess containing urine. To address this problem, we created bilateral PNs. As we were concerned that the regular US replacement was impairing his QoL, we decided to perform urinary rediversion from the CU to a new ileal conduit.

Surgical procedure

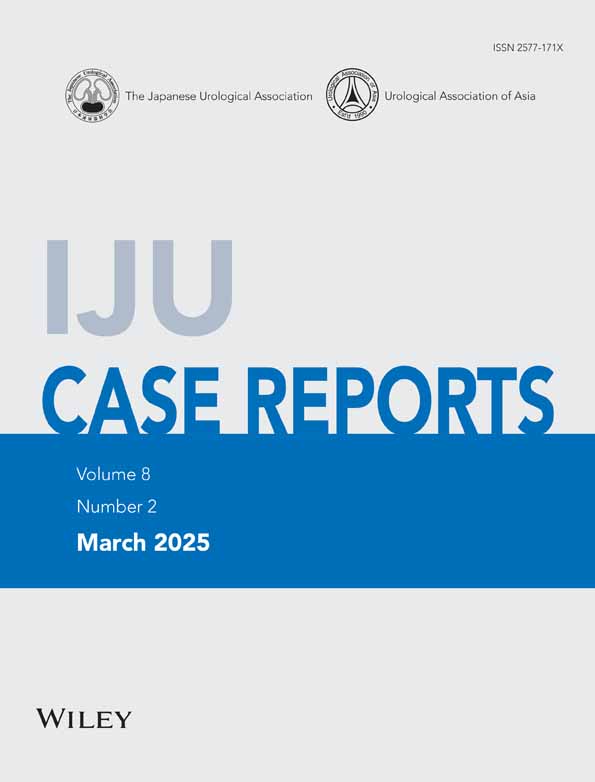

The procedure was performed with the patient in a supine position. Despite his medical history, there were only mild adhesions in the abdominal cavity and the intestinal tracts were easily separated. We taped the bilateral ureters near the ileocecal area and dissected the ureters. During this process, we did not detach the taped ureters proximally. We confirmed the ureteral blood flow both visually and using ICG fluorescence to determine the optimal location for the ureter–conduit anastomosis (Fig. 1a).

We decided to free 25 cm of the proximal end of the ileal stoma and 2 cm of the distal end of the ileal stoma by designing it into an ileal conduit approximately 20 cm in length (Fig. 1b). We performed the ureter–ileum anastomosis by the Nesbit procedure. We placed the ileal conduit stoma at the same site as the CU. During the procedure, we also closed his temporary ileostomy on the left side of his abdomen.

The total operation time was 7 h and 27 min, with approximately 500 mL of blood loss.

Postoperative course

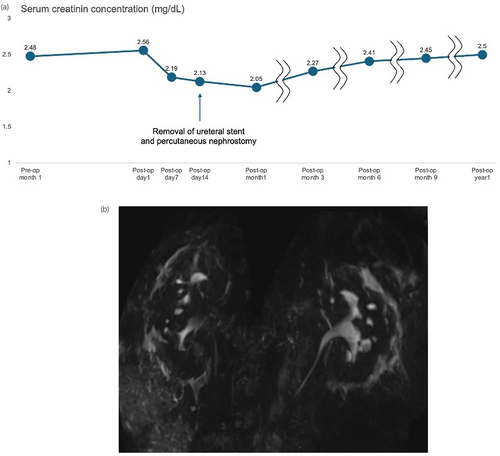

The postoperative course was almost uneventful. We removed the USs on postoperative day 14. Despite the presence of grade 1 left hydronephrosis, there was no increase in the serum creatinine concentration or flank pain after the removal of the USs. While the postoperative course of the urinary tract system was uneventful, a surgical site infection occurred. On postoperative day 9, the wound dehisced and leaked pus. We implemented daily wound washing, necrotic tissue excision, and application of ointments, and performed wound reconstruction under general anesthesia on postoperative day 28. Eventually, he was discharged with only a urostomy on postoperative day 37.

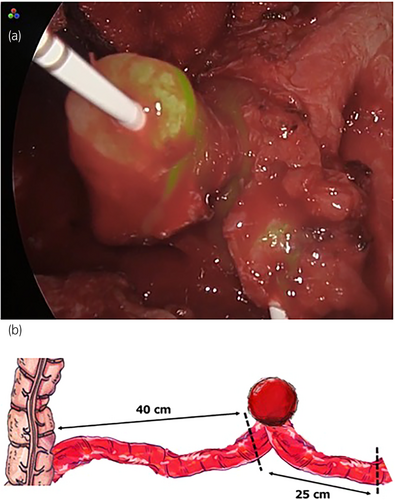

During follow-up, the left hydronephrosis resolved and the serum creatinine concentration was 2.41 mg/dL, representing only a moderate decrease from the preoperative concentration (Fig. 2a,b). Nine months after surgery, the patient was able to return to social activities (Fig. 3a–c).

Discussion

While a CU is generally considered a lower complication rate procedure than IC, it is concerning that CUs often result in ureteral strictures.1 In the short term, PN is a valid option for patients with complications from ureteral stricture secondary to CU, as in the present case. However, we do not consider PN to be an appropriate long-term management strategy. Patients with PN require routine replacements and are at risk of complications such as dislodgment, UTIs, and obstruction. Therefore, we considered creating a new ileal conduit for urinary rediversion to enable the patient to be catheter-free. However, the procedure is challenging due to difficulty in maneuvering the adhered ureters. Furthermore, there were concerns about the development of stenosis of the ureter-conduit anastomosis postoperatively. In general, anastomotic stenosis is known to be caused by impaired blood flow.2 Hence, we implemented the following two techniques. First, we minimized the dissection of the bilateral ureters as much as possible; this enabled us to preserve the blood flow of the ureters, which is necessary for implantation. Second, we performed the anastomosis between the ureter and conduit in ureteral regions with a rich blood supply. We confirmed the blood flow visually and using ICG fluorescence. Although the use of ICG is considered off-label in Japan, we obtained approval to use ICG from the Ethics Committee of Uji-Tokushukai Medical Center (approval number: 2023–06). Shen et al. reported that confirming the ureteral blood flow using visual inspection and ICG fluorescence prevents stenosis of the anastomosis.3

In addition, we need to mention about his renal function. As shown in Fig. 2a, his renal function gradually decreased after the procedure. We believe that the causes were chronic urinary tract obstruction, urine absorption in the ileal conduit and his medical history of diabetes mellitus. The procedure addressed one of the causes of kidney damage. If we had not performed the procedure, his impairment of renal function would have progressed more. Additionally, we, as urologists, should consider the methods of urinary diversion from the viewpoint of renal function. However, we prioritized his wishes for social recovery over the mild impairment of his renal function.

To our knowledge, there have been only four reported cases of urinary rediversion to an ileal conduit (Table 1).4-6 All four reports describe successful procedures without mentioning any complications. The small number of reported cases relative to the potential number of cases with ureteral stricture secondary to CU may be attributed to the avoidance of surgery due to the previously mentioned risks. However, in cases like the present one where serious complications arise and there is a need for improvement in mid- to long-term QoL, although the ileostomy closure may have contributed to some improvement in his QoL, rediversion to an ileal conduit may be beneficial. We were able to succeed in the surgery in this case because of the aforementioned techniques. However, due to the small number of case reports, it is difficult to conclude that rediversion surgery is generally recommended. Further research is warranted.

| Authors | Preoperative condition | Reason for rediversion | Complication | Catheter-free |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iketani (2000)4 | Bilateral ureterosigmoidostomy | Recurrent UTI | None | Achieved |

| Pak (1986)5 | Bilateral CU | Recurrent UTI | None | Achieved |

| Pain | ||||

| Catheter obstruction | ||||

| Yoshida (1982)6 | Bilateral CU | Recurrent UTI | None | Achieved |

| Bilateral CU | Recurrent UTI | None | Achieved | |

| Urinary tract stone formation |

Conclusions

Urinary rediversion with a new ileal conduit may be considered one of the treatment options for ureteral stenosis secondary to CU. Additional case studies are warranted to establish the optimal indications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kelly Zammit, BVSc, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Yu Tashiro: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing; writing – original draft. Mami Yamazaki: Writing – review and editing. Yasuaki Katsunaga: Writing – review and editing. Go Takeuchi: Writing – review and editing. Satoshi Nagayama: Writing – review and editing. Yasumasa Shichiri: Writing – review and editing. Masaaki Ito: Writing – review and editing; supervision.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study trial

Not applicable.

Funding information

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.