Masked acute rejection of the graft kidney under the recovery of native kidneys in a patient who underwent simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation

Abstract

Introduction

Simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation is a life-saving procedure for patients with liver failure and irreversible renal dysfunction. However, some studies have reported the recovery of native renal function after simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman initially underwent living-donor liver transplantation for liver failure. When graft liver failure developed, she also sustained acute renal failure and required continuous hemodiafiltration for 6 weeks. Simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation from a brain-dead donor recovered her liver and renal function. A 1-year protocol graft kidney biopsy revealed acute cellular rejection despite stable serum creatinine levels. Renal scintigraphy showed functional native kidneys masking acute rejection of the graft kidney. The rejection was improved by pulse steroid therapy.

Conclusion

Acute rejection of the graft kidney may silently progress due to recovery of the native kidney function after simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation. Renal scintigraphy and graft kidney biopsy should be considered even if blood tests indicate stable total renal function.

Abbreviations & Acronyms

-

- CHDF

-

- continuous hemodiafiltration

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- OPTN

-

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

-

- SLKT

-

- simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation

Keynote message

It is difficult to predict recovery of the native kidney function after SLKT. Functional native kidneys may mask acute rejection of the graft kidney. Therefore, renal scintigraphy and graft kidney biopsy should be considered after SLKT to evaluate the individual functions of native and graft kidneys.

Introduction

SLKT has recently been gaining attention as the treatment of choice in patients with liver failure and concurrent renal dysfunction.1, 2 Although simultaneous kidney transplantation is indicated only for irreversible renal dysfunction, it is often difficult to predict recovery from liver failure-induced acute kidney injury after LT alone. Indeed, it was reported that the recovery of native renal function was observed in 32–52.2% of SLKT recipients.3-5

An incidence of rejection to kidney graft in SLKT recipients is lower than in those of renal transplant alone.6 However, compromised renal function due to rejection has been reported in SLKT recipients,7 suggesting the need for optimal monitoring during follow-up.

Here we present a case of acute T cell-mediated rejection without changes in serum creatinine levels that were detected on a protocol biopsy 1 year after SLKT. We observed recovery of native renal function that had masked the graft kidney function impairment. Thus, the management of the present case highlights the need for specific care and attention to monitoring renal function in SLKT recipients, particularly those with sustained pretransplantation acute kidney injury.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman was diagnosed to have liver and kidney failures after a living-donor LT from her mother. She had initially presented with portal hypertension due to hepatic arterioportal shunt, which had subsequently progressed to severe liver failure. Unfortunately, the first transplantation had failed due to delayed primary dysfunction and the patient had developed renal dysfunction for which CHDF was introduced.

An SLKT from a brain-dead donor was performed 2 months after the first transplantation. By that time, she had been on CHDF for 6 weeks and her renal failure was considered irreversible. The donor was a man in his 20s who died of a head injury. The kidney transplantation was performed after the LT with the standard procedure, and a graft biopsy at 1 h after blood reperfusion showed no abnormalities. The posttransplantation course was uneventful; the serum bilirubin and creatinine levels rapidly decreased, prompting CHDF withdrawal on day 5 after surgery. The maintenance immunosuppression regimen consisted of prednisolone (5 mg/day), mycophenolate mofetil (1500 mg/day), and tacrolimus (target trough concentration of 3–5 ng/mL); the serum creatinine levels were stable around 0.6 mg/dL (Fig. 1).

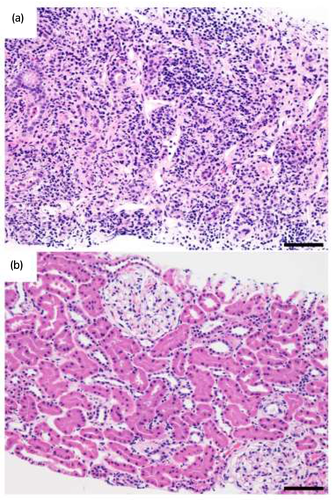

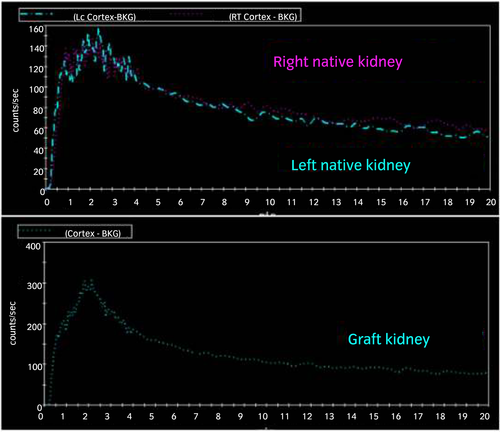

According to our protocol, a graft kidney biopsy was performed at 4 months after SLKT, showing modest cellular infiltration around the glomeruli with mild interstitial fibrosis. The pathological diagnosis was borderline changes (Banff: t3, i1, g1, v0), and the patient was placed under observation with stable serum creatinine levels. However, a protocol biopsy conducted 1 year after the transplantation showed acute T cell-mediated rejection (Banff: t3, i2, g0, v0, ptc0) (Fig. 2a). 99mTc-mercaptoacetyltriglycine renal scintigraphy revealed recovered native renal function (Fig. 3) with individual effective renal plasma flows (mL/min/1.73 m2) of 223.2 for the graft kidney, 84.9 for the right native kidney, and 95.3 for the left native kidney. Pulse steroid therapy was administered, and a confirmatory – performed 2 months after 1 year biopsy – biopsy showed no remaining signs of acute rejection (Banff: t0, i0, g0, v0) (Fig. 2b). Target tacrolimus trough levels were increased to 4–6 ng/mL thereafter; the patient is doing well with normal hepatic and renal functions at 2 years post-SLKT.

Discussion

For a long time, there used to be no standard criteria for LT candidates on SLKT since it is difficult to predict the postoperative recovery of renal function. Indeed, many centers used to utilize their own criteria for simultaneous kidney transplantation8 until the OPTN incorporated new and strict criteria for liver and kidney transplantations in 2017.2 For those with sustained acute kidney injury, it requires at least one of the following criteria or a combination of both during the preceding 6 weeks: (i) glomerular filtration rate ≤25 mL/min at least once every 7 days; or (ii) being on dialysis at least once every 7 days.

We considered the present case met the OPTN criteria, as the patient had been on CHDF required for over 6 weeks. Nonetheless, native renal function was restored by 1 year after the transplantations. According to previous reports, 32–52.2% of patients recovered their native kidney function after SLKT.3-5 Practically, however, it is very difficult to know whether post-SLKT recovery of total renal function depends on the graft or native kidney, or both.5

Blood tests, such as serum creatinine, are widely used for the early detection of graft kidney dysfunction because renal function in kidney transplant recipients almost completely depends on the graft kidney. When native kidney function is restored, as in the present case, graft kidney rejection may not be detected by tests representing total renal function.

Some investigators reported that a simultaneously transplanted liver could protect the kidney allograft against rejection, and the rate of acute rejection episodes in the kidney was low.4, 9, 10 On the other hand, Nilles et al. reported that various forms of kidney rejection occurred in approximately 20% of SLKT recipients, indicating that the transplanted liver may not always confer complete immunological tolerance.7 Thus, physicians should be aware of both native kidney function recovery and graft kidney rejection in SLKT recipients. The usefulness of renal scintigraphy for evaluating the individual functions of native and graft kidneys was reported.3 The authors believe that individual kidney function should be evaluated with renal scintigraphy 6–12 months after SLKT. When native kidney function recovery is demonstrated on renal scintigraphy, a protocol biopsy should be more strongly considered to monitor graft function, which can consequently improve the prognosis of the kidney graft in SLKT recipients.11, 12

Conclusions

Since SLKT recipients sometimes achieve native kidney function recovery, which makes early detection of graft kidney rejection using serum creatinine monitoring difficult, functional and pathological evaluations of each individual kidney should be considered.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.