Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and inflammatory markers associated with gallbladder dysplasia: A case–control analysis within a series of patients undergoing cholecystectomy

Abstract

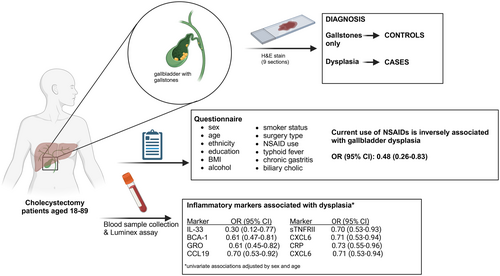

Inflammation has been associated with the development of gallbladder cancer (GBC). However, little is known about the associations of both, inflammation and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), with preneoplastic lesions. We analyzed the association of NSAIDs and gallbladder dysplasia in 82 patients with dysplasia and 1843 patients with gallstones among symptomatic patients from a high-risk population. We also analyzed associations for 33 circulating immune-related proteins in a subsample of all 68 dysplasia cases diagnosed at the time of sample selection and 136 gallstone controls. We calculated age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Biliary colic was reported among most cases (97.6%) and controls (83.9%). NSAID use was inversely associated with gallbladder dysplasia (OR: 0.48, 95%CI: 0.26–0.83). Comparing the highest versus lowest category of each immune-related protein, eight proteins were inversely associated with dysplasia with sex- and age-adjusted ORs ranging from 0.30 (95%CI: 0.12–0.77) for IL-33 to 0.76 (95%CI: 0.59–0.99) for MIP-1B. Of those, GRO remained associated with dysplasia (OR: 0.64, 95%CI: 0.45–0.91) and BCA-1 was borderline associated (OR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.54–1.01) after adjusting the logistic regression model for sex, age, and NSAIDs. In conclusion, NSAID users were less likely to have gallbladder dysplasia, suggesting that NSAIDs might be beneficial for symptomatic gallstones patients. The inverse association between immune-related markers and dysplasia requires additional research, ideally in prospective studies with asymptomatic participants, to understand the role of the inflammatory response in the natural history of GBC and to address the biological effect of NSAIDs.

Graphical Abstract

What's new?

Gallbladder cancer is associated with inflammation, especially in the context of gallstones. However, little is known about the association between inflammation or the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and pre-neoplastic lesions. In this case–control study of patients with symptomatic gallstones, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use was inversely associated with gallbladder dysplasia. Moreover, circulating inflammatory markers tended to exhibit lower levels in patients with dysplasia compared to gallstone patients with less severe diagnoses. The identification of factors associated with dysplasia, the stage prior to gallbladder cancer, might help guide future prevention and early detection efforts.

1 INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is an aggressive cancer, with a median survival time of 6 months.1 Although GBC is rare worldwide, high incidence rates have been observed in South America, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.2 In particular, Chile has one of the highest age-standardized incidence rates of 16/100,000 for women and 5/100,000 for men in the southern-central region.3 The poor prognosis of GBC, mostly due to its late diagnosis and limited effective treatments, underlines the urgent need for early GBC detection and prevention strategies.

GBC is associated with inflammation, especially in the context of gallstones.2, 4-7 Gallstones, which are the main risk factor for GBC, promote chronic inflammation due to persistent damage in the mucosa of the gallbladder.4, 8 The sustained inflammatory response may promote genetic alterations like TP53 mutation and COX-2 overexpression, contributing to the development of GBC through metaplasia-dysplasia preneoplastic lesions.4 Histopathological changes in the gallbladder mucosa are associated with inflammation in patients with gallstones, characterized by high infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages, and upregulation of COX-2.5-7 Additionally, we have shown that high levels of circulating inflammatory proteins were associated with gallstones and GBC.9-11 For example, gallstone patients had higher levels of IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12p70 than population-based controls,9 and GBC patients had increased levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), CCL20, IL-16, sTNFRI and sTNFRII compared to gallstones controls.10, 11 In the case of early stages of GBC, inflammation has been studied mainly in murine models. Increased infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages and upregulation of cytokines, such as IL-1beta, have been shown in gallbladders from in vivo models of gallstones induced by a lithogenic diet.8, 12, 13 Moreover, patients with hyperplasia and metaplasia have been shown to have high infiltration of inflammatory cells in the gallbladder mucosa.6 However, the association of inflammatory markers and preneoplastic lesions in patients with gallstones is unclear.

In addition to gallstones, other risk factors like a high-fat diet, obesity, and chronic bacterial infections, such as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, have also been associated with increased risk of GBC.2, 14, 15 These factors could contribute to a chronic inflammatory environment, promoting the development of GBC. In contrast, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) has been associated with decreased risk of GBC,16-18 as well as other inflammatory-associated gastrointestinal cancers, such as colon and stomach cancer.19, 20 These studies suggest that inflammatory pathways could be targeted for cancer prevention. However, there are concerns about whether the observed associations are due to the biological effect of NSAIDs or bias, such as healthy-user and healthy-adherer effects. Hence, more evidence is needed to understand the potential protective effect of anti-inflammatory drugs for GBC development.

To address these questions, we explored whether NSAID use impacts the gallbladder carcinogenesis process early by assessing the association of NSAIDs and inflammatory markers with gallbladder dysplasia, the precursor to GBC. Studying gallbladder dysplasia can provide valuable insight into how inflammation promotes GBC development and can provide more confidence in the etiologic factors associated with GBC. A better understanding of the factors associated with the stages of disease progression leading to GBC, including elucidation of risk factors for progression through the metaplasia-dysplasia cascade, might help identify better strategies for cancer prevention and early detection of GBC.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study population and samples: the Cholecystectomy Research Study (CRS)

From May 2014 to May 2019, we enrolled 1949 cholecystectomy patients with ultrasound-detected gallstones from three hospitals (Sótero del Río Hospital, Clínica Dávila and Public Hospital San José) in Santiago, Chile. These patients included all consecutive programmed cholecystectomy patients aged 18–89 years having surgery during business hours for whom we could collect pre-surgery blood and a subset of patients having urgent surgery (on weekends or after hours) when staff were available for recruitment. Participants who were not mentally capable of answering the study questionnaire, had received a previous cholecystectomy, or for whom we could not obtain pre-surgery blood were excluded from our study. Blood was collected from patients prior to cholecystectomy (before their histopathological diagnosis) to ensure that inflammatory proteins were not influenced by the surgery itself. Samples were processed within 3.5–5 h of blood draw and stored at −80°C for further analysis. Prior to surgery, we also collected epidemiologic information including sociodemographic and lifestyle data, and presence of biliary colic from each participant or their medical records. To increase the detection of gallbladder pre-neoplastic lesions, for each patient, nine sections (3 sections from the neck, body, and fundus of the gallbladder) were processed and reviewed by hospital pathologists. For a subset of 117 participants (42 with diagnoses less severe than dysplasia, 62 low-grade dysplasia, 3 unclassified dysplasia, 6 high-grade dysplasia and 4 GBC), digital H&E slide images were reviewed by two independent-blinded pathologists to confirm histopathological diagnosis; 96% of diagnoses agreed (112/117). For individuals with disagreement, a blinded third pathologist reviewed the digital images to determine the final diagnosis.

Of the 1949 CRS participants with gallstones, at the time of serum sample selection for immune markers measurement, 68 participants were diagnosed with gallbladder dysplasia (termed “dysplasia cases”; 60 low-grade, 5 high-grade and 3 indefinite dysplasia), 10 with GBC (termed “GBC cases”) and 1513 with less severe diagnoses (termed “controls”); the remaining 358 individuals received diagnoses after the time of sample selection (Figure S1). Controls were matched to dysplasia and GBC cases on sex, hospital and age (±5 years difference). From among all potential controls for each case, two were randomly selected (2:1 ratio) from those with a blood draw date no more than 60 days apart from the case. Thus, 68 dysplasia cases and 136 matched controls were analyzed to evaluate the associations of inflammatory proteins and dysplasia. Also, we explored the associations of these proteins and GBC using 10 GBC cases and 20 matched controls.

To study the associations of NSAIDs and dysplasia, we included the 14 dysplasia cases and 330 controls (344 total) who had not received diagnoses at the time of sample selection for the immune marker analysis (Figure S1). After confirmation of diagnosis, 1843 controls and 82 dysplasia cases (total N = 1925) were analyzed to evaluate the associations of NSAIDs and dysplasia. The 24 GBC cases were excluded from this analysis due to low sample size.

2.2 Laboratory procedures

We measured 66 circulating immune-related proteins in 234 serum samples (68 dysplasia cases and 136 controls; 10 GBC cases and 20 controls) using the Milliplex assay (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Serum samples were incubated with beads in 96-well plates and afterward, fluorescently labeled detection antibodies were added. The 96-well plates were analyzed using a modified flow cytometer (Bio-Plex 200, Bio-Rad), and data were reported as pg/ml using Bio-Plex Manager 6.1, as we have previously described.10, 11 To evaluate assay performance, we calculated the coefficients of variation (CVs) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) using 78 serum samples from 12 non-CRS cholecystectomy subjects recruited in Temuco and Pucón, Chile.21 CVs and ICCs were calculated based on a linear regression model fit to the log-transformed observed concentrations, as previously described.9 Analytes detectable in <25% of samples from these 12 non-CRS subjects, with a CV > 30%, or an ICC < 0.7 were excluded from the final analysis. Thirty-three of the 66 analytes (Table S1) were dropped due to these criteria, leaving 33 proteins to be analyzed.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics, including sex, age, self-reported ethnicity (Chilean/Latino, Mapuche), education (0–8, 9–12 and ≥ 13 years of schooling), smoking status (never, former, current), body mass index (BMI; categorical: normal weight1: ≥18.5 to <25 kg/m2, overweight: ≥25 to <30 kg/m2 and obese: ≥30 kg/m2), consumption of alcohol during the last year (no alcohol and >1–30 days per month), surgery type (elective or urgent), current use of non-aspirin NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, ketorolac and diclofenac; use one or more times during the last week), and presence of biliary colic (ever/never; episode of severe pain in the pit of the stomach or under the right ribs that lasted more than 30 min without diarrhea), typhoid fever and chronic gastritis were compared between dysplasia cases and controls using chi-square tests. We also explored the association of these variables with dysplasia using multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for sex and categorical age (<40, 40–50, 51–60 and > 60 years) in the minimally adjusted models and sex, age, the remaining sociodemographic and lifestyle variables, NSAID use, surgery type, biliary colic, typhoid fever and chronic gastritis in the fully adjusted models. Observations with missing data were excluded from the regression analyses. In addition, we assessed the association of NSAID use and dysplasia in normal weight, overweight and obese patients separately to identify effect modification of the NSAIDs-dysplasia association, i.e. interactions of NSAID use and BMI. For this analysis, we fit logistic regression models within each BMI category, adjusting for sex and categorical age, and we evaluated the interaction between NSAIDs and BMI by adding an interaction term between NSAIDs and BMI to this model. Two-sided Wald p-values were calculated.

For the immune-related protein analyses, as described previously,10, 11 samples with measurements below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) were assigned a value of half the LLOQ, and measurements above the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) were assigned the ULOQ value. Immune-related proteins were analyzed as categorical variables according to the proportion of subjects with detectable values as follows: (a) for proteins detectable in ≥75% of subjects, 4 categories were created based on quartiles of values above the LLOQ where subjects with undetectable values were included in the lowest quartile; (b) for detectable proteins in 50–75% of subjects, 4 categories were created: the first one included all subjects with undetectable values and the remaining 3 categories were based on tertiles of values above the LLOQ; (c) for detectable proteins in 25–50% of subjects, 3 categories were created: the first category included all subjects with undetectable values and the next 2 categories were split based on their median of the values above the LLOQ; (d) for low detectable proteins (<25%), 2 categories were created: one for values below the LLOQ and the other for values above the LLOQ.10, 11

For the biomarker component of the study, we first calculated partial Spearman rank correlations between the categorical immune-related proteins and patient characteristics in cases and controls separately, controlling for categorical age and sex using the pcor.test function in the R package ppcor.22

To evaluate the association of circulating immune-related proteins with dysplasia vs. controls, we included each marker separately in a conditional logistic regression model including categorical age (<40, 40–50, 51–60 and > 60 years) and sex. Immune-related proteins were modeled as ordinal variables to evaluate linear trend, and p-trend across categories was calculated using Wald tests. We provide the ordinal ORs, which reflect the linear change per category. We applied a multiple testing adjustment to all markers except for four a priori-identified immune-related markers, IL-16, CCL20, sTNFRI and CRP, which increased the risk of early GBC (p-values ≤ .001) in a prior study.11 Moreover, all immune-related markers associated with dysplasia (p-trend < .05) were included jointly in a multivariable logistic model, which was additionally adjusted for age, sex, and current use of NSAIDs. Furthermore, we fit a polytomous logistic regression model to assess the association of each marker, adjusted by categorical age and sex, with dysplasia and GBC outcomes as the case groups.

We explored the associations between current use of NSAIDs and each circulating immune-related protein using ordinal logistic regression models with markers categories as the outcome variable and NSAID use as the independent predictor, adjusted for age and sex (minimally adjusted) and surgery type as additional adjustment (fully adjusted). For IL-33, which had only two categories, we used a binomial logistic regression model. Characteristics of current NSAIDs users and non-users were compared using chi-square tests.

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.1.23

3 RESULTS

The 1925 CRS participants with and without dysplasia were similar except for current use of NSAIDs, biliary colic, and BMI (Table 1). Dysplasia cases were less likely to report current use of NSAIDs than controls (17.1% vs. 30.7%) and were more likely to report biliary colic (97.6% vs. 83.9%). Surprisingly, dysplasia cases were less likely to be obese than controls (25.6% vs. 38.7%).

| Controls, N = 1843 | Dysplasia, N = 82 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, N (%) | ||

| Women | 1441 (78.2) | 64 (78.0) |

| Men | 402 (21.8) | 18 (22.0) |

| Age, mean ± SD (min–max) | 45.8 ± 15.2 (18–89) | 48.5 ± 15.0 (19–89) |

| Categorical age, N (%) | ||

| < 40 years | 690 (37.4) | 21 (25.6) |

| 40–50 years | 440 (23.9) | 28 (34.1) |

| 51–60 years | 364 (19.8) | 17 (20.7) |

| > 60 years | 349 (18.9) | 16 (19.5) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | ||

| Chilean/Latino | 1743 (94.6) | 79 (96.3) |

| Mapuche | 66 (3.6) | 2 (2.4) |

| N/A | 34 (1.8) | 1 (1.2) |

| Education, N (%) | ||

| 0–8 years | 515 (27.9) | 22 (26.8) |

| 9–12 years | 928 (50.4) | 43 (52.4) |

| ≥ 13 years | 284 (15.4) | 10 (12.2) |

| N/A | 116 (6.3) | 7 (8.5) |

| Categorical BMI, N (%) | ||

| Normal weight | 349 (18.9) | 25 (30.5) |

| Overweight | 765 (41.5) | 35 (42.7) |

| Obese | 714 (38.7) | 21 (25.6) |

| N/A | 15 (0.8) | 1 (1.2) |

| Consumption of alcohol in the last year, N (%) | ||

| No alcohol | 1168 (63.4) | 54 (65.9) |

| More than 1 days per month | 673 (36.5) | 28 (34.1) |

| N/A | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Smoker status, N (%) | ||

| Never smoker | 1579 (85.7) | 75 (91.5) |

| Former smoker | 104 (5.6) | 3 (3.7) |

| Current smoker | 160 (8.7) | 4 (4.9) |

| Surgery type, N (%) | ||

| Urgent | 431 (23.4) | 17 (20.7) |

| Elective | 1411 (76.6) | 65 (79.3) |

| N/A | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Current use of NSAIDs, N (%) | ||

| No | 1277 (69.3) | 68 (82.9) |

| Yes | 565 (30.7) | 14 (17.1) |

| N/A | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Typhoid fever, N (%) | ||

| No | 1740 (94.4) | 78 (95.1) |

| Yes | 59 (3.2) | 3 (3.7) |

| N/A | 44 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) |

| Chronic gastritis, N (%) | ||

| No | 1738 (94.3) | 78 (95.1) |

| Yes | 61 (3.3) | 3 (3.7) |

| N/A | 44 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) |

| Biliary colic, N (%) | ||

| No | 258 (14.0) | 2 (2.4) |

| Yes | 1546 (83.9) | 80 (97.6) |

| N/A | 39 (2.1) | 0 (0) |

- Abbreviation: N/A, not available.

Minimally and fully adjusted logistic models produced similar associations for dysplasia vs. controls (Table 2). In the fully adjusted model, NSAID use and obesity were inversely associated with dysplasia (OR: 0.37; 95% CI: 0.17–0.78 and OR: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.22–0.79, respectively). In contrast, biliary colic was positively associated with dysplasia (OR: 7.63; 95% CI: 2.31–47.13).

| Variable | Controls | Dysplasia | Minimally adjusteda | Fully adjustedb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1843 | N = 82 | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | ||||||

| Chilean/Latino | 1743 (94.6) | 79 (96.3) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Mapuche | 66 (3.6) | 2 (2.4) | 0.69 (0.11–2.28) | .614 | 0.65 (0.10–2.19) | .561 |

| Education, N (%) | ||||||

| 0–8 years | 515 (27.9) | 22 (26.8) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| 9–12 years | 928 (50.4) | 43 (52.4) | 1.15 (0.65–2.07) | 1.28 (0.71–2.37) | ||

| ≥ 13 years | 284 (15.4) | 10 (12.2) | 0.96 (0.41–2.11) | .99 | 1.13 (0.47–2.56) | .652 |

| Categorical BMI, N (%) | ||||||

| Normal weight | 349 (18.9) | 25 (30.5) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Overweight | 765 (41.5) | 35 (42.7) | 0.64 (0.38–1.10) | 0.64 (0.36–1.13) | ||

| Obese | 714 (38.7) | 21 (25.6) | 0.41 (0.23–0.75) | .004 | 0.42 (0.22–0.79) | .007 |

| Consumption of alcohol in the last year, N (%) | ||||||

| No alcohol | 1168 (63.4) | 54 (65.9) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| >1 days per month | 673 (36.5) | 28 (34.1) | 0.91 (0.56–1.45) | .7 | 0.85 (0.50–1.40) | .530 |

| Smoker status, N (%) | ||||||

| Never smoker | 1579 (85.7) | 75 (91.5) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Former smoker | 104 (5.6) | 3 (3.7) | 0.64 (0.15–1.78) | 0.81 (0.19–2.36) | ||

| Current smoker | 160 (8.7) | 4 (4.9) | 0.57 (0.17–1.39) | .207 | 0.49 (0.12–1.37) | .227 |

| Surgery type, N (%) | ||||||

| Urgent | 431 (23.4) | 17 (20.7) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Elective | 1411 (76.6) | 65 (79.3) | 1.11 (0.66–1.98) | .714 | 0.72 (0.35–1.58) | .4 |

| Current use of NSAIDs, N (%) | ||||||

| No | 1277 (69.3) | 68 (82.9) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Yes | 565 (30.7) | 14 (17.1) | 0.48 (0.26–0.83) | .014 | 0.37 (0.17–0.78) | .012 |

| Typhoid fever, N (%) | ||||||

| No | 1740 (94.4) | 78 (95.1) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Yes | 59 (3.2) | 3 (3.7) | 1 (0.24–2.80) | 1 | 1.25 (0.29–3.66) | .716 |

| Chronic gastritis, N (%) | ||||||

| No | 1738 (94.3) | 78 (95.1) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Yes | 61 (3.3) | 3 (3.7) | 1.04 (0.25–2.89) | .954 | 0.95 (0.22–2.71) | .927 |

| Biliary colic, N (%) | ||||||

| No | 258 (14.0) | 2 (2.4) | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Yes | 1546 (83.9) | 80 (97.6) | 7.28 (2.26–44.52) | .006 | 7.63 (2.31–47.13) | .005 |

- Note: p-value was calculated by Wald test.

- a Adjusted for categorical age (<40, 40–50, 51–60 and > 60 years) and sex.

- b Adjusted for categorical age, sex, Mapuche ethnicity, education, smoker habit, alcohol consumption, current use of NSAIDs, surgery type, typhoid fever, chronic gastritis and biliary colic.

We further evaluated a possible interaction of obesity with NSAIDs given that obesity is also related to inflammation24 and GBC15 by first evaluating the association of NSAID use and dysplasia within each BMI category (Table S2). We found that NSAID users were less likely to have dysplasia with an OR of 0.30 (95% CI: 0.07–0.90) compared to non-users among patients with normal weight. The association was weaker among overweight (OR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.18–1.12) and obese (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.23–1.84) participants. However, there was no evidence of interaction on a multiplicative scale between categorical BMI and current use of NSAIDs (pinteraction of .5 and .2 for the interaction term of overweight and obesity with NSAID use; respectively), although sample size was limited.

3.1 Association of circulating inflammatory markers and dysplasia

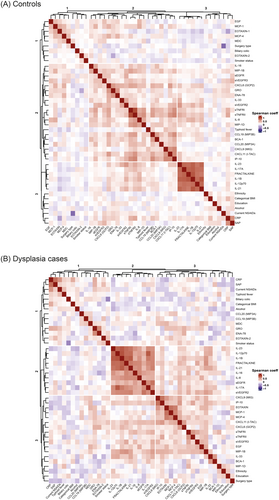

In a subset of 204 participants (68 dysplasia cases and 136 matched-controls), we evaluated the association between circulating inflammatory markers and dysplasia. First, we explored the correlations between inflammatory markers in controls and dysplasia cases, separately. We identified two groups of strongly positively correlated (coeff ≥ 0.6) immune-related markers in both, controls and cases. The first group included IL-23, FRACTALKINE, IL-17A, IL-12p70, IL-1B and IL-21, and the second group CXCL9, IP-10, sTNFRI, sTNFRII (Figure 1A,B; Table S3).

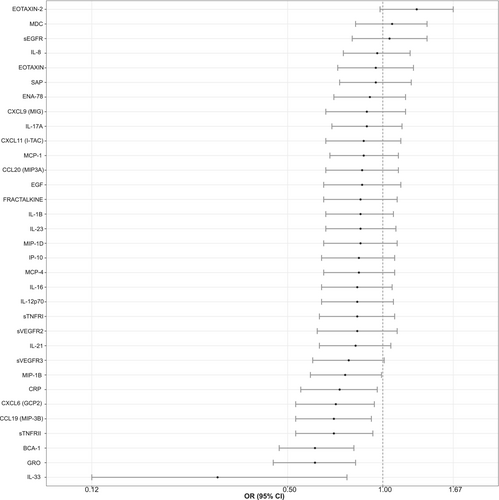

Next, we evaluated associations between the markers and dysplasia. Eight of the 33 immune-related markers (IL-33, BCA-1, GRO, CCL19 (MIP-3B), sTNFRII, CXCL6 (GCP2), CRP and MIP-1B) were inversely associated with dysplasia, with univariate ORs ranging from 0.30 (95%CI: 0.12–0.77) for IL-33 to 0.76 (95%CI: 0.59–0.99) for MIP-1B (Figure 2; Table S4). After Bonferroni adjustment, only GRO and BCA-1 remained statistically significantly associated (Table S4). The eight markers that exhibited univariate associations were not strongly correlated with each other (Spearman coeff < 0.6; Table S3). In a logistic regression model that included these eight markers jointly (adjusted for age, sex, and current use of NSAIDs), only GRO remained statistically significantly inversely associated with dysplasia with an OR (95% CI) of 0.64 (0.45–0.91), although BCA-1 showed a borderline association with dysplasia (OR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.54–1.01; Table S4).

Further, we explored the associations between inflammatory markers and GBC. More markers tended to be positively associated with GBC versus controls than dysplasia versus controls (Figure S2). For example, the OR for the association between CRP and GBC was 1.69 (95% CI: 0.86–3.34), whereas the association with dysplasia was inverse (OR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.54–0.95) (Figure S2; Table S4). However, the number of GBC cases was very small (N = 10), requiring a larger study to fully characterize these associations.

3.2 Circulating inflammatory markers in NSAIDs users

To illuminate the inverse association between immune-related markers and dysplasia, we evaluated the associations between current use of NSAIDs and immune-related markers in controls and dysplasia cases, separately. After adjusting for categorical age, sex and surgery type, current use of NSAIDs was associated with increased levels of sVEGFR3 (OR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.12–6.33) and GRO (OR: 2.55, 95% CI: 1.11–6.01) in controls and with higher levels of CRP (OR: 4.61, 95% CI: 1.47–15.64) in dysplasia cases (Tables 3 and 4).

| Outcome: categorical marker | Minimally adjusteda | Fully adjustedb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| sVEGFR3 | 2.53 (1.26–5.19) | .010 | 2.61 (1.12–6.33) | .030 |

| GRO | 2.30 (1.13–4.76) | .023 | 2.55 (1.11–6.01) | .029 |

| CRP | 2.11 (1.07–4.17) | .031 | 1.99 (0.88–4.55) | .101 |

| ENA-78 | 1.94 (0.98–3.88) | .059 | 1.65 (0.74–3.72) | .223 |

| BCA-1 | 1.87 (0.95–3.72) | .071 | 2.62 (1.16–6.05) | .022 |

| MIP-1B | 1.80 (0.92–3.57) | .089 | 1.63 (0.74–3.60) | .221 |

| sTNFRII | 1.79 (0.87–3.70) | .112 | 1.81 (0.79–4.13) | .159 |

| sTNFRI | 1.62 (0.82–3.19) | .164 | 1.53 (0.70–3.38) | .289 |

| MCP-1 | 1.57 (0.81–3.07) | .179 | 1.38 (0.63–3.04) | .416 |

| CXCL6 (GCP2) | 1.55 (0.80–3.05) | .198 | 1.11 (0.50–2.45) | .804 |

| CCL19 (MIP-3B) | 1.54 (0.79–3.04) | .208 | 2.46 (1.09–5.70) | .032 |

| IL-21 | 1.41 (0.72–2.75) | .313 | 1.09 (0.49–2.41) | .836 |

| sVEGFR2 | 1.38 (0.71–2.69) | .349 | 1.99 (0.89–4.51) | .094 |

| MCP-4 | 1.25 (0.64–2.41) | .514 | 1.15 (0.52–2.51) | .725 |

| IL-8 | 1.21 (0.62–2.39) | .573 | 0.78 (0.35–1.72) | .539 |

| IL-16 | 1.17 (0.58–2.35) | .653 | 1.35 (0.58–3.12) | .485 |

| MIP-1D | 1.11 (0.55–2.23) | .777 | 1.46 (0.65–3.32) | .360 |

| CXCL11 (I-TAC) | 1.09 (0.56–2.14) | .799 | 1.07 (0.49–2.34) | .865 |

| CXCL9 (MIG) | 1.08 (0.55–2.11) | .832 | 1.18 (0.54–2.60) | .679 |

| EOTAXIN-2 | 1.08 (0.54–2.14) | .834 | 0.95 (0.43–2.10) | .901 |

| IL-17A | 1.03 (0.53–1.99) | .934 | 0.71 (0.33–1.54) | .393 |

| CCL20 (MIP-3A) | 0.99 (0.50–1.92) | .966 | 1.04 (0.46–2.37) | .920 |

| IL-12p70 | 0.99 (0.51–1.93) | .988 | 0.84 (0.37–1.89) | .676 |

| IL-1B | 0.94 (0.48–1.84) | .85 | 0.87 (0.39–1.93) | .738 |

| IL-23 | 0.90 (0.46–1.76) | .749 | 0.90 (0.40–2.00) | .796 |

| SAP | 0.88 (0.45–1.71) | .707 | 0.84 (0.38–1.84) | .663 |

| sEGFR | 0.85 (0.43–1.67) | .636 | 1.04 (0.47–2.29) | .931 |

| MDC | 0.82 (0.41–1.60) | .552 | 1.47 (0.65–3.36) | .353 |

| EGF | 0.74 (0.37–1.47) | .396 | 0.62 (0.27–1.40) | .252 |

| IP-10 | 0.71 (0.35–1.41) | .326 | 0.82 (0.36–1.86) | .640 |

| FRACTALKINE | 0.63 (0.32–1.26) | .196 | 0.57 (0.25–1.26) | .165 |

| EOTAXIN | 0.59 (0.30–1.15) | .12 | 0.72 (0.31–1.65) | .432 |

- a Adjusted for categorical age and sex.

- b Adjusted for categorical age, sex and elective versus urgent surgery.

| Outcome: categorical marker | Minimally adjusteda | Fully adjustedb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| CRP | 5.70 (1.83–19.27) | .004 | 4.61 (1.47–15.64) | .011 |

| SAP | 2.47 (0.81–7.83) | .116 | 2.09 (0.67–6.71) | .207 |

| GRO | 2.38 (0.80–7.22) | .120 | 2.71 (0.88–8.59) | .084 |

| EOTAXIN-2 | 1.77 (0.58–5.61) | .317 | 2.07 (0.67–6.68) | .209 |

| CXCL6 (GCP2) | 1.71 (0.57–5.27) | .341 | 2.12 (0.67–6.85) | .201 |

| MIP-1D | 1.60 (0.50–5.11) | .425 | 1.60 (0.48–5.23) | .436 |

| ENA-78 | 1.59 (0.55–4.70) | .397 | 1.72 (0.56–5.37) | .341 |

| MCP-4 | 1.52 (0.49–4.73) | .463 | 1.70 (0.54–5.43) | .364 |

| sTNFRI | 1.26 (0.42–3.76) | .677 | 1.24 (0.39–3.89) | .711 |

| sVEGFR2 | 1.21 (0.39–3.80) | .743 | 1.18 (0.36–3.89) | .788 |

| IL-21 | 1.13 (0.36–3.50) | .827 | 0.98 (0.30–3.12) | .966 |

| CCL20 (MIP-3A) | 1.12 (0.30–3.97) | .861 | 1.12 (0.29–4.11) | .870 |

| BCA-1 | 1.09 (0.35–3.29) | .880 | 0.86 (0.26–2.69) | .798 |

| MCP-1 | 1.05 (0.36–3.02) | .927 | 1.01 (0.34–2.96) | .987 |

| CXCL11 (I-TAC) | 1.01 (0.33–3.10) | .980 | 0.93 (0.30–2.93) | .907 |

| sTNFRII | 0.93 (0.29–2.95) | .902 | 0.76 (0.22–2.53) | .660 |

| IL-16 | 0.87 (0.26–2.77) | .821 | 0.76 (0.21–2.60) | .668 |

| IL-8 | 0.78 (0.22–2.71) | .701 | 0.63 (0.16–2.27) | .480 |

| MIP-1B | 0.71 (0.21–2.31) | .575 | 0.68 (0.20–2.25) | .527 |

| MDC | 0.63 (0.19–1.99) | .429 | 0.68 (0.20–2.28) | .532 |

| sEGFR | 0.62 (0.19–2.02) | .430 | 0.47 (0.14–1.58) | .223 |

| sVEGFR3 | 0.61 (0.18–1.99) | .412 | 0.60 (0.17–2.03) | .408 |

| IL-12p70 | 0.60 (0.18–1.90) | .391 | 0.57 (0.17–1.85) | .356 |

| CCL19 (MIP-3B) | 0.59 (0.18–1.83) | .367 | 0.45 (0.13–1.47) | .197 |

| IL-1B | 0.52 (0.13–1.84) | .322 | 0.44 (0.11–1.60) | .225 |

| IL-23 | 0.50 (0.15–1.67) | .266 | 0.47 (0.13–1.60) | .232 |

| EOTAXIN | 0.49 (0.14–1.61) | .241 | 0.59 (0.17–2.08) | .412 |

| FRACTALKINE | 0.47 (0.14–1.55) | .222 | 0.45 (0.13–1.49) | .193 |

| IP-10 | 0.47 (0.14–1.51) | .209 | 0.41 (0.12–1.35) | .147 |

| IL-17A | 0.42 (0.12–1.32) | .147 | 0.41 (0.12–1.32) | .145 |

| EGF | 0.38 (0.11–1.32) | .129 | 0.37 (0.10–1.34) | .132 |

| CXCL9 (MIG) | 0.37 (0.09–1.33) | .138 | 0.29 (0.07–1.09) | .076 |

- a Adjusted for categorical age and sex.

- b Adjusted for categorical age, sex and elective versus urgent surgery.

Given the positive association of NSAIDs with sVEGFR3 and GRO in gallstones controls and with CRP in dysplasia cases, we added these three markers to the logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex and biliary colic for the subset of people with immune-related marker data. Adding these three markers to the model attenuated the inverse association between NSAIDs and dysplasia from 0.57 (95% CI: 0.27–1.14) to 0.79 (95% CI: 0.36–1.68).

Further, we compared the characteristics of current NSAID users to non-current users among all 1925 CRS patients (for controls and dysplasia cases, separately). Notably, among controls, current NSAID users were more likely to undergo urgent surgery (65.8% vs. 4.6%) and to report biliary colic (95.2% vs. 78.9%) than non-current NSAID users (Table S5). Similarly, among dysplasia cases, urgent surgery was more common in NSAID users than non-users (50% vs. 14.7%, Table S6).

4 DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first case–control study to evaluate the associations of NSAID use and circulating immune-related markers with gallbladder dysplasia among patients with symptomatic gallstones. We found that patients with dysplasia had lower levels of IL-33, BCA-1, GRO, CCL19 (MIP-3B), sTNFRII, CXCL6 (GCP2), CRP and MIP-1B compared to gallstones patients without dysplasia. When evaluating all CRS participants, we found that NSAID use was inversely associated with gallbladder dysplasia, with an OR of 0.37 (95% CI: 0.17–0.78).

An important aspect of our study is that all CRS patients have gallstones, which promote inflammation.2, 25 While the majority of individuals with gallstones are asymptomatic,25 most CRS patients (cases and controls) experienced biliary colic. Some may have taken NSAIDs to alleviate their symptoms. However, if the association were entirely due to biliary colic, one would expect to see a positive association between NSAID use and dysplasia. In our study, NSAIDs remained inversely associated with dysplasia after biliary colic adjustment, suggesting that the inverse association of NSAIDs and dysplasia was not biased due to symptoms.

The association of NSAIDs and dysplasia might also be influenced by other inflammation-related factors, like obesity.24 Obese patients might have increased levels of inflammatory proteins compared with non-obese patients. Hence, the use of NSAIDs might not have the same effect among all CRS patients. While the interaction between categorical BMI and NSAIDs was not statistically significant, the inverse association with dysplasia was strongest among patients with normal weight and weakest among obese patients. Similarly, Wang et al. found that NSAID use was strongly associated with reduced CRC risk among patients with normal weight whereas a mild protective effect was observed among overweight and obese patients.26 Taken together, these findings suggest that individuals with normal weight might be more likely to benefit from NSAID use.

Another concern might be that among symptomatic gallstone patients, those with severe symptoms might be more likely to use NSAIDs and undergo emergency surgery, potentially going to surgery before they develop dysplasia. We found that NSAID users were more likely to undergo urgent surgery. Hence, the inverse association of NSAIDs and dysplasia might be explained in part to earlier surgery of those patients with severe symptoms. While this explanation seems less likely given the strong association between biliary colic and dysplasia (OR: 7.63; 95% CI: 2.31–47.13), it is possible that symptom severity could have an impact. To avoid these issues, the association of NSAIDs and dysplasia would ideally be evaluated in ultrasound-detected gallstones patients, regardless of whether the gallstones are symptomatic or not. For example, the prospective Chile Biliary Longitudinal Study (Chile BiLS)27 offers a valuable setting for studying the potential impact of NSAIDs on gallbladder preneoplasia and will provide significant insights for a better understanding of the natural history of GBC. In particular, longitudinal measurements of immune-related markers are crucial to evaluate the potential beneficial effect of NSAID use on dysplasia and GBC.

This study also provides some hints as to a potential biologic mechanism for the inverse association between NSAID use and dysplasia. In the subset of participants with immune-related marker measurements, the age-, sex- and biliary colic-adjusted association between current use of NSAIDs and dysplasia was inverse, although not statistically significant (OR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.27–1.14). After including sVEGRF3, GRO and CRP (the immune-related markers associated with current use of NSAIDS) in the model, the association between NSAID use and dysplasia was attenuated (OR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.36–1.68). While this analysis was limited by sample size, the findings support the hypothesis that the association between NSAIDs and dysplasia might be mediated through immune-related processes.

Given that all participants in our study had gallstones, which cause tissue injury, promoting inflammation,2, 25 we expected the use of NSAIDs to reduce the levels of inflammation in our participants. Contrary to our expectations, current use of NSAIDs was associated with increased levels of sVEGFR3 and GRO in controls and with high levels of CRP in dysplasia cases after adjustment for age, sex, and surgery type. We also observed a higher frequency of biliary colic in NSAID users compared to non-users, which could be related to having increased inflammation due to more acute changes in the gallbladder in NSAID users. Greater frequency of acute gallbladder changes could also explain the higher likelihood of urgent (emergency) surgeries among NSAID users compared to non-users. Consistent with our findings, one study of colorectal adenoma reported that the use of NSAIDs was positively associated with high levels of other inflammatory proteins, IL-6 and TNF-alpha, which the authors concluded could be due to confounding by indication.28 Taken together, these results suggest that NSAID users could have higher baseline levels of immune-related proteins due to having more symptoms and acute changes in the gallbladder than non-users, resulting in a positive association between NSAIDs and inflammatory markers. For an accurate assessment of the effect of NSAIDs on systemic inflammation, longitudinal studies of immune-related proteins levels before and after taking NSAIDs are warranted.

Our results could also be influenced by the duration of NSAID use, which was not available in our study. Short- and long-term of NSAIDs has been associated with a reduced risk of gastrointestinal cancers. However, the strength of the effect seems to vary depending on the duration of NSAID use. In a randomized trial of 1121 patients with colorectal adenomas, one-year of low-dose of aspirin (81 mg per day) showed a moderate benefit in patients with advanced adenomas compared to the placebo group, with a relative risk of 0.59 (95% CI: 0.38–0.92).29 Additionally, a mild effect of a higher doses of aspirin (160 or 300 mg/day) over 1 year, showed a relative risk of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.52–1.04) in patients with a history of colorectal adenomas in the APACC intervention Trial.30 However, a prospective cohort study of 82,911 women showed that regular aspirin use ≥2 standard [325-mg] tablets within 1–5 and 6–10 years was not significantly associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer. A significant reduction in colorectal cancer risk was only shown in women who regularly used aspirin for more than 10 years of use (ptrend ≤ .001).31

Short-term use of NSAIDs may not be sufficient to reduce the high levels of inflammation seen in these symptomatic gallstones patients, resulting in elevated inflammatory markers in current-users compared to non-users, and/or in a small inverse association with gallbladder dysplasia. Measurement of the duration of NSAID use would facilitate understanding of potential differences in the effect of short- and long-term NSAID use on disease association. Even without information on duration of use, however, we showed an inverse association of NSAIDs with gallbladder dysplasia (OR: 0.48, 95%CI: 0.26–0.83).

We were also surprised to see a trend toward inverse associations between immune-related markers and gallbladder dysplasia given that gallstone-related GBC is associated with chronic inflammation4, 8, 10, 11, 32 and higher levels of immune-related markers compared to gallstone controls.10, 11 However, our inverse associations with dysplasia are consistent with a previous study that found that IL-2, IL-5, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13 and TNF-alpha tend to be downregulated in low-grade/moderate dysplasia of the pancreas compared to serous cystadenoma without dysplasia.33 Interestingly, in our study, the majority of dysplasias were low-grade. In the case of advanced lesions, pro-inflammatory cytokines like L-1beta, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-alpha were elevated in high-grade dysplasia/pancreatic cancer compared to low-grade/moderate dysplasia group,33, 34 suggesting that immune response patterns may change across the natural history of disease.

Furthermore, Delgiorno et al. and Leary et al. have shown that the levels of inflammation can be regulated by the presence of tuft cells, which are commonly present in the normal digestive and biliary tracts, and the amount of tuft cells can change as cancer progresses.35-37 Delgiorno et al. (2014) found that these cells are present in higher amounts in metaplasia but absent in pancreatic cancer. In addition, they showed that the depletion of these cells accelerates tumor progression in vivo accompanied by upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines.36 Furthermore, Leary et al.37 showed that that the depletion of these cells in the gallbladder promotes neutrophil infiltration and upregulation of cytokines, which could favor tumor progression. Moreover, gallstone formation could be promoted by tuft cells due to their sensitivity to bile acids, which can favor the development of GBC.37 Taken together, these findings suggest that levels of inflammatory proteins might change across metaplasia-dysplasia-GBC sequence which might explained the inverse association between inflammatory markers and dysplasia. Longitudinal studies are warranted to study the associations of inflammatory markers and gallbladder preneoplastic lesions.

Although we previously observed higher levels of immune-related markers in GBC cases,10, 11 we had limited ability to evaluate associations with GBC in the current study given the small number of cases. However, the association with inflammatory markers tended to be in a positive direction more often for GBC than for dysplasia in the current study. Longitudinal studies with larger numbers of GBC and dysplasia cases are warranted to assess inflammatory markers in the progression of GBC.

This study has several strengths. It is the first to our knowledge to assess the association of NSAID use and inflammatory markers with dysplasia, a precursor to GBC. We included surgery type and biliary colic in our analysis to address confounding by indication. Diagnosis misclassification was minimized through an extensive pathology review. Our study also has some limitations. For example, the size of the subsample with immune-related marker data limited the power to assess complex associations. Larger sample sizes are also needed to address the association between inflammation and GBC. Although we evaluated confounders, our results could be influenced by additional patient characteristics such as diet, use of medications and exercise, which were not measured in our study.

The potential for confounding is always of concern in studies of NSAIDs. Although symptoms can influence NSAID use, the inverse association between NSAID use and dysplasia remained after adjusting for symptoms, including biliary colic, and multiple other confounders. Diet, which was not measured in our study, could also affect the association of NSAIDs and gallbladder dysplasia since symptomatic patients may avoid high-fat diets to prevent nausea and bloating, cause for example by fried and fatty foods,25 and be more likely to use NSAIDs to alleviate pain from gastrointestinal symptoms. While we did not have information on diet, we did adjust for obesity, which is correlated with dietary behaviors. Taken together, we think it likely that the inverse association between NSAIDs and gallbladder dysplasia reflects a true association.

In summary, we found that NSAID use was inversely associated with gallbladder dysplasia among symptomatic patients. Additional studies, especially longitudinal studies with rich biorepositories, are needed to better understand whether NSAID use is biologically associated with gallbladder dysplasia and cancer, and if so, how NSAIDs influence disease progression and might be leveraged in effective prevention strategies. Moreover, immune-related markers tended to be inversely associated with dysplasia, suggesting a regulation of immune response at early stages in the natural history of GBC. Future studies at early stages of precursor lesions are warranted to understand the role of chronic inflammation and immune response in GBC progression.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lorena Rosa: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Paz Cook: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Ruth M. Pfeiffer: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; supervision; writing – review and editing. Troy J. Kemp: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Allan Hildesheim: Conceptualization; formal analysis; writing – review and editing. Burcin Pehlivanoglu: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Volkan Adsay: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Enrique Bellolio: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Juan Carlos Araya: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Ligia Pinto: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Catterina Ferreccio: Conceptualization; formal analysis; funding acquisition; methodology; writing – review and editing. Gloria Aguayo: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Eduardo Viñuela: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Jill Koshiol: Conceptualization; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Carolina Miranda, Patricio Madrid, María Lucía Escobar for their participation in the pathology review; Dr. Alfonso Díaz, Dr. Marcel Sanhueza, Dr. Nicolás Quezada and Dr. Alejandro Brañez for surgical practice; Daniela Soto and María Eliana Órdenes for assistance in patient recruitment and coordination of data and sample collection; Carolina Riveros, Jennifer Vilo, Vanessa Van de Wyngard, Ian Reyes and Miguel Carrera for support with study and data/sample management; Michael Curry and Greg Rydzack of Information Management Services, Inc., for analytical support; and Myron Levine and Rossana Lagos for providing data and samples from patients recruited in Clínica Dávila and Public Hospital San José.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by general funds from the Intramural Research Program of the US National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, and the Office of Research on Women's Health, National Institutes of Health. This research was also funded by Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT Regular 1,212,066) and Fondo de Financiamiento de Centros de Investigación en Áreas Prioritarias (FONDAP) (grant number 15130011).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All participants provided written consent for biospecimen and questionnaire data collection, and the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and the Chilean Ministry of Health ethical review boards approved this study.

PREVIOUS PRESENTATION

This work was previously presented in the poster section at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) in San Diego, California, USA, and was published as part of the conference proceedings in the abstract book: Cancer Res (2024) 84 (6_Supplement): 3446.

Endnote

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data contributing to the paper will be deposited in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (DCEG-PDR) at the National Cancer Institute, under controlled access with the following data use limitations: disease-specific (gallbladder disease), sensitive data, such as Mapuche ethnicity, will not be shared. Further information is available from the corresponding authors upon request.