Associations between low- and high-fat dairy intake and recurrence risk in people with stage I–III colorectal cancer differ by sex and primary tumour location

Abstract

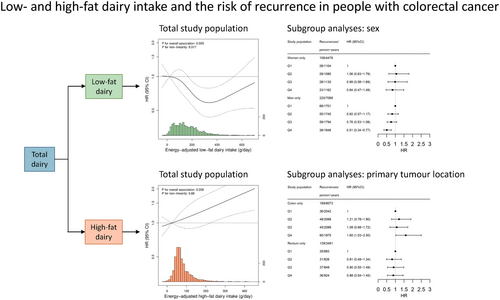

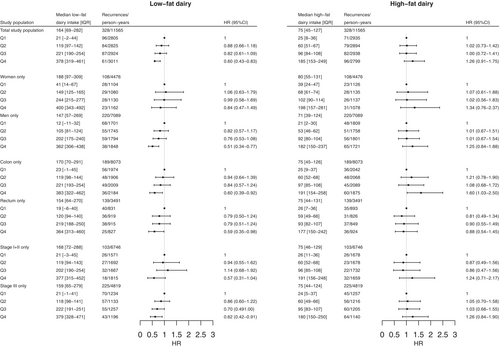

We previously demonstrated that intake of low-fat dairy, but not high-fat dairy, was associated with a decreased colorectal cancer (CRC) recurrence risk. These risks, however, may differ by sex, primary tumour location, and disease stage. Combining data from two similar prospective cohort studies of people with stage I–III CRC enabled these subgroup analyses. Participants completed a food frequency questionnaire at diagnosis (n = 2283). We examined associations between low- and high-fat dairy intake and recurrence risk using multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, stratified by sex, and primary tumour location (colon and rectum), and disease stage (I/II and III). Upper quartiles were compared to lower quartiles of intake, and recurrence was defined as a locoregional recurrence and/or metastasis. During a median follow-up of 5.0 years, 331 recurrences were detected. A higher intake of low-fat dairy was associated with a reduced risk of recurrence (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.60, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.43–0.83), which seemed more pronounced in men (HR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.34–0.77) than in women (HR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.47–1.49). A higher intake of high-fat dairy was associated with an increased risk of recurrence in participants with colon cancer (HR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.03–2.50), but not rectal cancer (HR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.54–1.45). No differences in associations were observed between strata of disease stage. Concluding, our findings imply that dietary advice regarding low-fat dairy intake may be especially important for men with CRC, and that dietary advice regarding high-fat dairy intake may be specifically important in people with colon cancer.

Graphical Abstract

What's new?

There is strong evidence that dairy intake is associated with a reduced risk of developing colorectal cancer. However, its relation to the risk of colorectal cancer recurrence remains unclear. Combining data from two prospective cohort studies of patients with stage I–III colorectal cancer, this study found that a higher intake of low-fat dairy was associated with a reduced risk of recurrence in men, where as a higher intake of high-fat dairy was associated with an increased risk of recurrence in people with colon cancer. With a global transition towards more plant-based diets and increasing numbers of colorectal cancer survivors, the findings may contribute to more personalised dietary guidelines.

1 INTRODUCTION

There is strong evidence that dairy intake is associated with a reduced risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC).1, 2 However, even though some studies have assessed the intake of different types of dairy and dairy products in relation to CRC-specific mortality,3-7 no studies thus far other than our previous work8 have assessed its relation to a more direct indicator of neoplastic growth after diagnosis: the risk of CRC recurrence. We previously observed that a higher pre-diagnostic intake of low-fat dairy, but not high-fat dairy, was associated with a reduced risk of recurrence in people with stage I–III CRC.8 The current study includes a larger study population with more recurrence data available, which enables us to build on our previous findings by identifying clinically relevant subgroups of individuals who may benefit most from dietary advice regarding dairy intake.

Tumour recurrences develop in 3%–38% of individuals with CRC within 3 years after a resection with curative intent, depending on stage at diagnosis.9 Risk of recurrence has been reported to be higher in men than in women, and in people with rectal cancer compared to people with colon cancer.9, 10 Furthermore, the localisation of recurrences also seems to differ per location of the primary tumour,9, 11 and may differ for men and women,11 implying different underlying mechanisms are involved leading to cancer recurrence.

The association between dairy intake and risk of recurrence may also differ for subgroups of people with CRC based on sex, primary tumour location, and disease stage. First, prior studies have demonstrated that higher intakes of low-fat dairy7 and calcium from dairy12 may be associated with a reduced risk of CRC-specific mortality in men, but not in women. Second, colon and rectal cancer differ in terms of embryonical origin, genetic and molecular characteristics, microbiome, oncogenesis, and treatment,9, 13 and may also have different risk factors for recurrence.9 Thirdly, taking into account the wide variation in risk of recurrence across different stages of disease at diagnosis,9 we aim to study whether dairy intake is similarly related to risk of recurrence for stages I–III of disease.

Based on our previous work,8 where we observed a reduced risk of recurrence and all-cause mortality with higher intakes of low-fat dairy, but an increased risk of all-cause mortality with higher intakes of high-fat dairy, we assess low- and high-fat dairy separately in the current study. Hypotheses about how dairy components influence risk of recurrence in CRC are largely derived from research on the risk of CRC occurrence. Calcium may decrease risk of CRC via binding secondary bile acids and free fatty acids in the colonic lumen, and by inhibiting cell proliferation, promoting cell differentiation, and inducing apoptosis in tumour cells.14-20 Lactic acid-producing bacteria in fermented dairy have been proposed to inhibit colorectal neoplastic growth.2, 21 Furthermore, it has been proposed that dairy intake may affect microbial diversity and associated microbial metabolites in the gut,22 thereby inhibiting neoplastic growth of the colonocytes.23

With the current study we aim to investigate the association between low- and high-fat dairy intake and risk of CRC recurrence in subgroups of sex, primary tumour location and stage at diagnosis. These subgroup variables are usually readily available in clinical practice and do not require further testing, ultimately enhancing the applicability of our results in daily practice.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study population

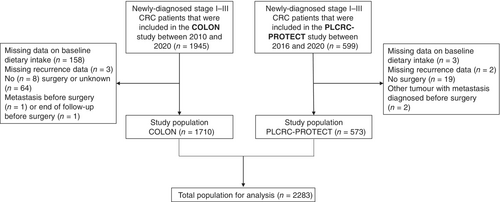

The initial study population consisted of 2544 adults who were newly diagnosed with stage I–III CRC, from two prospective cohort studies: the COLON study (n = 1945)24 and the PLCRC-PROTECT study (n = 599).25 Details of the COLON study and overall PLCRC study have been described previously.24, 25 Briefly, participants of the COLON study were recruited from 11 hospitals in the Netherlands between August 2010 and February 2020. Recruitment for the PLCRC-PROTECT study started in February 2016 and was ongoing at the time of data analysis in 21 hospitals in the Netherlands. Participants who were recruited before December 2020 were included in the current study population. For the current analyses, we excluded participants with missing data on dietary intake (n = 161), missing data on recurrence (n = 5), no confirmed surgery (n = 91), and those who appeared to have a metastasis before surgery (n = 3) or whose follow-up ended before surgery (n = 1) (Figure 1). The final population for analysis contained 2283 participants.

2.2 Assessment of exposure

In both studies, participants filled out an identical self-administered semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) of 204 items at diagnosis,26, 27 reflecting on dietary intake in the month prior to the measurement. Building on our previous work,8 which showed associations between dairy intake at diagnosis, but not 6 months after diagnosis, in relation to risk of recurrence, the current study focuses on pre-diagnostic dairy intake.

Dietary intake of low-fat dairy and high-fat dairy was calculated in grams per day. Low-fat dairy included low-fat or skimmed versions of milk, yoghurt, custard, and soft curd cheese. High-fat dairy included whole-fat versions of milk, yoghurt, custard, soft curd cheese, and all other cheeses, condensed milk, ice cream, whipped cream, and butter. Ready-made breakfast drinks were not included, because not all ready-made breakfast drinks on the Dutch market contain dairy. Energy and nutrient intakes were calculated using the online Dutch Food Composition Table (version 2011/3.0).28 Low- and high-fat dairy intakes were adjusted for total energy intake using the energy residual method.29 To improve interpretability, the predicted dairy intake at the median total energy intake was added to individual residuals. Mean differences between absolute and energy-adjusted intakes were very minimal: energy-adjusted low- and high-fat dairy intakes were on average 3 (SD: 31) and 4 (SD: 36) g/day lower than absolute intakes, respectively.

2.3 Assessment of outcome

Recurrences were defined as a locoregional recurrence and/or metastasis occurring after surgery. Locoregional recurrence was defined as a recurrence in the same segment as the primary tumour, in the lymph nodes of the same segment, or in the draining lymph nodes. For both cohorts, updated recurrence data were requested from the Netherlands Cancer Registry via the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation.

Follow-up time was calculated starting from date of surgery until date of recurrence, until the date recurrence status was updated, or until end of follow-up (e.g., due to death, occurrence of another primary tumour with metastasis, or moving abroad), whichever came first. If date of surgery was unavailable (n = 2), date of filling out the FFQ was used.

2.4 Assessment of covariates

At diagnosis, participants from both cohorts also filled out a questionnaire on demographics, anthropometrics, cancer family history, and lifestyle habits, including questions about age (years), sex (man/woman), education (low/medium/high), body weight (kg), height (cm), smoking status (current/former/never), and calcium and vitamin D supplement use in the past year (including multivitamins, yes/no). Physical activity was assessed using the Short QUestionnaire to ASsess Health-enhancing physical activity (SQUASH).30 Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (hours/week) included all activities with a metabolic equivalent value ≥3 according to Ainsworth et al.31 Clinical data, such as disease stage (I–III), tumor location (colon: caecum to the sigmoid colon; rectum: rectosigmoid junction and rectum) and type of treatment (only surgery, surgery and chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy, surgery and chemoradiation) were collected via the Dutch ColoRectal Audit (COLON)32 or the Netherlands Cancer Registry (PLCRC-PROTECT). To assess possible confounding by other dietary factors previously associated with CRC risk,2 we also calculated total intake of wholegrains, red meat, processed meat, dietary fibre, and alcohol. Definitions of red and processed meat were as in the Continuous Update Project Expert report of 2018 from the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research.2

2.5 Data analysis

Sex-specific quartiles of dairy intake were constructed. Population characteristics are presented as medians [interquartile range (IQR)] or numbers (percentage).

Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were used to calculate Hazard Ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the associations between low- and high-fat dairy intake and risk of recurrence, and for the associations between low- and high-fat dairy and total recurrence in strata of sex (man/woman), primary tumour location (colon/rectum), and stage of disease at diagnosis (I–II/III). Log–log curves were visually inspected for non-parallelism to check the proportionality assumption for the Cox proportional hazards model. The lowest quartile was used as the reference category in categorical analyses. ptrend values were computed over quartiles of intake using the medians of the corresponding quartiles. For continuous analyses, increments of 100 g/day were used. First, a crude model was created, adjusting for age and sex (except for analyses in strata of sex). Then, potential confounders were added to the model when they changed the HR by >10%. The following covariates were considered as confounders based on literature: primary tumour location (except for analyses in strata of primary tumour location), disease stage (except for analyses in strata of disease stage), BMI (continuous), education level (low, medium, high), smoking status (current, former, never), moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (continuous), and total dietary intake of wholegrains, dietary fibre, red meat, processed meat and alcohol (g/day). The fully adjusted model included age, sex, disease stage, and total daily intakes of energy, dietary fibre, and alcohol. Simultaneous adjustment for high-fat dairy (in low-fat dairy analyses) and low-fat dairy (in high-fat dairy analyses) did not change conclusions.

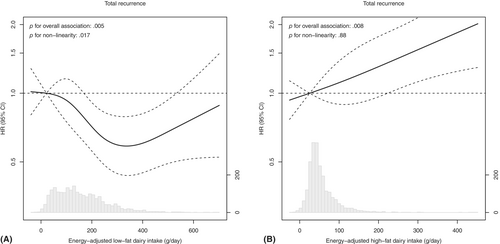

We also evaluated restricted cubic splines (RCS) to study linearity of the associations between dairy exposures and CRC recurrence, using the fully adjusted model. For low-fat dairy, the model was observed to fit best with 4 knots based on Akaike's information criterion, and knots were placed at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentile. For high-fat dairy, the model was observed to fit best with 3 knots, and knots were placed at the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentile. Graphs were truncated at the 1st and 99th percentile. The median intake of the first quartile of each exposure was used as the reference.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted excluding participants who had a recurrence within 6 months after filling out the FFQ, and those who were diagnosed with CRC before the age of 50 years. As butter has a specifically high fat content within the high-fat dairy category, we also conducted analyses for high-fat dairy intake excluding butter.

Data analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.0.5). p-values below .05 were considered statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

Participants were on average 66 years (IQR: 60–72) at CRC diagnosis, and 38% were woman (Table 1). Participants in the highest quartile of low-fat dairy intake (with a median energy-adjusted intake of 378 g/day) were older, less often current smokers, consumed more dietary calcium, and consumed less high-fat dairy and alcohol, compared to participants in the lowest quartile of low-fat dairy intake (with a median energy-adjusted intake of 21 g/day). Participants in the highest quartile of high-fat dairy intake (with a median energy-adjusted intake of 186 g/day) were older, had a lower level of education, more often had a tumour in the proximal colon, consumed more dietary calcium, and consumed less total energy, dietary fibre, wholegrains, low-fat dairy, processed meat, and alcohol, compared to participants in the lowest quartile of high-fat dairy intake (with a median energy-adjusted intake of 25 g/day).

| Characteristics | Total population (n = 2283) | Quartile of energy-adjusted dairy intake | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-fat dairy | High-fat dairy | ||||

| Q1 (n = 571) | Q4 (n = 571) | Q1 (n = 571) | Q4 (n = 571) | ||

| Age, years | 66 [60–72] | 65 [59–71] | 67 [60–73] | 64 [58–69] | 67 [62–73] |

| Women | 863 (37.8) | 216 (37.8) | 216 (37.8) | 216 (37.8) | 216 (37.8) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.0 [23.9–28.7] | 25.7 [23.6–28.3] | 26.3 [24.2–28.7] | 25.7 [23.9–28.4] | 25.4 [23.2–28.1] |

| Waist-hip-ratio | 0.95 [0.90–1.01] | 0.95 [0.90–1.00] | 0.95 [0.90–1.00] | 0.95 [0.89–1.01] | 0.95 [0.90–1.00] |

| Level of educationa | |||||

| Low | 899 (39.4) | 225 (39.4) | 219 (38.4) | 197 (34.5) | 251 (44.0) |

| Medium | 586 (25.7) | 145 (25.4) | 143 (25.0) | 156 (27.3) | 138 (24.2) |

| High | 788 (34.5) | 196 (34.3) | 205 (35.9) | 217 (38.0) | 175 (30.6) |

| Unknown | 10 (0.4) | 5 (0.9) | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.2) |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Current | 209 (9.2) | 81 (14.2) | 35 (6.1) | 50 (8.8) | 59 (10.3) |

| Former | 1312 (57.5) | 316 (55.3) | 318 (55.7) | 332 (58.1) | 318 (55.7) |

| Never | 715 (31.3) | 164 (28.7) | 202 (35.4) | 181 (31.7) | 180 (31.5) |

| Unknown | 47 (2.1) | 10 (1.8) | 16 (2.8) | 8 (1.4) | 14 (2.5) |

| Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, hours/weekb | 11 [5–19] | 11 [5–20] | 12 [6–20] | 12 [6–20] | 10 [5–19] |

| Calcium supplement userc | 498 (21.8) | 127 (22.2) | 124 (21.7) | 123 (21.5) | 117 (20.5) |

| Vitamin D supplement userd | 708 (31.0) | 170 (29.8) | 186 (32.6) | 188 (32.9) | 171 (29.9) |

| Dietary intake | |||||

| Total energy, kcal/day | 1794 [1482–2159] | 1832 [1487–2205] | 1825 [1543–2163] | 2005 [1688–2339] | 1825 [1517–2180] |

| Low-fat dairy, g/day, energy-adjusted | 164 [69–282] | 21 [−2–44] | 378 [319–461] | 203 [88–326] | 112 [31–222] |

| High-fat dairy, g/day, energy-adjusted | 75 [45–126] | 94 [53–172] | 62 [38–100] | 25 [7–37] | 186 [153–249] |

| Milk, g/day, energy-adjusted | 51.9 [15.2–144.1] | 20.2 [−2.2–42.3] | 175.6 [51.2–291.2] | 33.9 [0.5–133.6] | 67.4 [21.4–165.1] |

| Yoghurt, g/day, energy-adjusted | 73.2 [19.3–141.3] | 19.6 [2.9–64.7] | 136.4 [55.3–240.5] | 60.0 [10.4–138.8] | 98.2 [40.1–166.7] |

| Cheese, g/day, energy-adjusted | 27.0 [15.6–42.0] | 25.9 [14.2–43.1] | 26.0 [14.4–39.1] | 17.2 [8.5–26.9] | 30.7 [17.3–48.6] |

| Dietary fibre, g/day | 19.6 [15.7–24.3] | 18.8 [15.2–23.4] | 20.5 [16.7–24.9] | 22.5 [18.9–26.8] | 19.0 [14.9–23.9] |

| Wholegrains, g/day | 107.3 [73.0–148.3] | 102.0 [65.0–145.3] | 112.8 [76.9–152.2] | 124.3 [82.9–167.7] | 99.4 [62.9–140.6] |

| Red meat, g/day | 34.3 [19.5–48.5] | 34.6 [18.7–50.1] | 34.7 [19.5–46.9] | 37.3 [23.3–51.1] | 31.2 [18.9–44.8] |

| Processed meat, g/day | 26.7 [12.9–43.5] | 29.9 [14.1–45.8] | 24.8 [13.3–44.4] | 33.1 [16.0–50.8] | 24.4 [11.1–40.0] |

| Alcohol, g/day | 7.9 [0.9–20.5] | 9.6 [1.0–24.1] | 5.0 [0.7–16.0] | 12.3 [2.3–26.9] | 4.3 [0.1–14.5] |

| Dietary calcium, mg/day | 851 [647–1079] | 669 [512–906] | 1081 [895–1301] | 828 [614–1048] | 950 [766–1209] |

| Saturated fat, g/day | 25 [19–32] | 27 [20–33] | 24 [19–31] | 24 [19–30] | 28 [23–36] |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Location of the tumoure | |||||

| Proximal colon | 709 (31.1) | 174 (30.5) | 173 (30.3) | 165 (28.9) | 200 (35.0) |

| Distal colon | 853 (37.4) | 222 (398.9) | 234 (41.0) | 222 (38.9) | 186 (32.6) |

| Rectum | 719 (31.5) | 174 (30.5) | 164 (28.7) | 184 (32.2) | 185 (32.4) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Disease stage | |||||

| I | 630 (27.6) | 157 (27.5) | 163 (28.5) | 155 (27.1) | 155 (27.1) |

| II | 629 (27.6) | 146 (25.6) | 163 (28.5) | 161 (28.2) | 170 (29.8) |

| III | 1002 (43.9) | 264 (46.2) | 238 (41.7) | 248 (43.4) | 243 (42.6) |

| Unknown | 22 (1.0) | 4 (0.7) | 7 (1.2) | 7 (1.2) | 3 (0.5) |

| Type of treatmentf | |||||

| Surgery only | 1280 (56.1) | 306 (53.6) | 331 (58.0) | 318 (55.7) | 320 (56.0) |

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 562 (24.6) | 161 (28.2) | 130 (22.8) | 143 (25.0) | 135 (23.6) |

| Surgery + radiotherapy | 228 (10.0) | 50 (8.8) | 57 (10.0) | 49 (8.6) | 64 (11.2) |

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 213 (9.3) | 54 (9.5) | 53 (9.3) | 61 (10.7) | 52 (9.1) |

- Note: Values are presented as median [IQR] or number (percentage).

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

- a Low education was defined as primary school and lower general secondary education; medium as lower vocational training and higher general secondary education; high as higher vocational training and university.

- b Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity included all activities with a metabolic equivalent value ≥3.31 Data were missing for 99 participants.

- c Data was missing for 28 participants.

- d Data were missing for 24 participants.

- e Proximal colon includes the caecum, appendix, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, and transverse colon. Distal colon includes the splenic flexure, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. Rectum includes the rectosigmoid junction and rectum.

- f Treatment includes neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment.

During a median follow-up time of 5.0 years (IQR: 3.0–7.3), 331 recurrences were detected. A higher intake of low-fat dairy was associated with a reduced risk of recurrence in the total population (HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.43–0.83, p for overall association: .005, p for non-linearity: .017, Table 2, Figure 2A). When assessing the relationship between low-fat dairy intake and risk of recurrence in subgroups, a higher intake of low-fat dairy was associated with a reduced risk of recurrence in men (HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.34–0.77), while no statistically significant association was observed in women (HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.47–1.49) (Figure 3). A higher intake of low-fat dairy was associated with a reduced risk of recurrence in participants with colon (HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.39–0.92) and rectal cancer (HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.35–0.98). Similarly, a higher intake of low-fat dairy tended to be associated with a reduced risk of recurrence in participants with stage I–II disease (HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.31–1.04) and stage III disease (HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.42–0.91).

| Dietary variable | Total recurrence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median energy-adjusted intake [IQR]a | n | No. of recurrences/person-years | Model 1 HR (95% CI)b | n | No. of recurrences/person-years | Model 2 HR (95% CI)c | |

| Low-fat dairy | |||||||

| Q1 | 21 [−2–44] | 571 | 97/2823 | 1.00 | 567 | 96/2805 | 1.00 |

| Q2 | 119 [97–142] | 570 | 84/2866 | 0.85 (0.63–1.14) | 564 | 84/2825 | 0.88 (0.66–1.18) |

| Q3 | 221 [190–254] | 571 | 89/2941 | 0.88 (0.66–1.17) | 566 | 87/2924 | 0.82 (0.61–1.09) |

| Q4 | 378 [319–461] | 571 | 61/3059 | 0.60 (0.44–0.83) | 564 | 61/3011 | 0.60 (0.43–0.83) |

| ptrend | .003 | .002 | |||||

| Continuous (per 100 g/day) | 164 [69–282] | 2283 | 331/11,689 | d | 2261 | 328/11,565 | d |

| High-fat dairy | |||||||

| Q1 | 25 [7–37] | 571 | 73/2964 | 1.00 | 564 | 71/2935 | 1.00 |

| Q2 | 60 [51–67] | 570 | 80/2925 | 1.03 (0.74–1.42) | 565 | 79/2894 | 1.02 (0.73–1.42) |

| Q3 | 96 [84–108] | 571 | 82/2978 | 1.03 (0.75–1.43) | 564 | 82/2938 | 1.00 (0.72–1.41) |

| Q4 | 186 [153–249] | 571 | 96/2822 | 1.30 (0.96–1.78) | 568 | 96/2799 | 1.26 (0.91–1.75) |

| ptrend | .06 | .11 | |||||

| Continuous (per 100 g/day) | 75 [45–126] | 2283 | 331/11,689 | 1.16 (1.05–1.27) | 2261 | 328/11,565 | 1.18 (1.06–1.31) |

- Note: Cut-off points for quartiles in women were as follows: 97.6, 188.7 and 309.3 g/day for low-fat dairy; 55.1, 79.9, and 130.4 g/day for high-fat dairy. Cut-off points for quartiles in men were as follows: 56.4, 147.2, 269.5 g/day for low-fat dairy; 38.6, 71.0, and 123.0 g/day for high-fat dairy.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range.

- a Dairy intake was adjusted for daily total energy intake using the energy residual method.29 To improve interpretability, the predicted dairy intake at the median total energy intake was added to individual residuals.

- b Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex and total energy intake (as part of the energy residual method).

- c Model 2 was additionally adjusted for disease stage, dietary fibre intake, and alcohol intake.

- d This association was observed to be non-linear in restricted cubic splines. See Figure 2 for the continuous analysis.

In contrast, a higher intake of high-fat dairy tended to be associated with a higher risk of recurrence (HRQ4 vs Q1: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.91–1.75, p for overall association: .008, p for non-linearity: .88, Table 2, Figure 2B). This association was similar but did not reach statistical significance for subgroups of sex and disease stage (Figure 3). For subgroups of primary tumour location, a higher intake of high-fat dairy was associated with a higher risk of recurrence in participants with colon cancer (HRQ4 vs Q1: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.03–2.50), while no association with risk of recurrence was observed in participants with rectal cancer (HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.54–1.45).

Sensitivity analyses excluding participants who had a recurrence within 6 months after filling out the FFQ (n = 20) did not substantially alter results (low-fat dairy intake in total study population: HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.43–0.84, p for overall association: 0.013, p for non-linearity: .038; high-fat dairy intake in total study population: HRQ4 vs Q1: 1.31, 95% CI: 0.93–1.84, p for overall association: .012, p for non-linearity: .79). Also, results did not change or were even slightly stronger when excluding participants with a CRC diagnosis before the age of 50 years (low-fat dairy intake in total study population: HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.43–0.84, p for overall association: .006, p for non-linearity: .017; high-fat dairy intake in total study population: HRQ4 vs Q1: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.00–1.97, p for overall association: .015, p for non-linearity: .93). Furthermore, excluding butter from high-fat dairy did not substantially change results for high-fat dairy (HRQ4 vs Q1: 1.28, 95% CI: 0.92–1.78, p for overall association: .032, p for non-linearity: .78).

4 DISCUSSION

In the current study, a higher intake of low-fat dairy was associated with a decreased risk of recurrence in people with stage I–III colorectal cancer, which seemed more pronounced in men than in women. In contrast, a higher intake of high-fat dairy tended to be associated with a higher risk of recurrence, which seemed limited to people with colon cancer.

Low- and high-fat dairy contained similar amounts of calcium in our study, but the saturated fatty acid content was higher in high-fat dairy than in low-fat dairy (weighted average saturated fat content: 9.1 g/100 g vs. 0.6 g/100 g). A previous study in people with metastatic colon cancer observed that replacing 5% of energy from carbohydrates with saturated fat was associated with an increased risk of cancer progression or death (HR: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.04–1.45), and that replacing 10% of energy from carbohydrates with animal fat tended to be associated with an increased risk of cancer progression or death (HR: 1.17, 95% CI: 0.98–1.40).33 However, no significant associations were observed when assessing quartiles of saturated fat or animal fat intake, which was also observed in previous work of the same authors in people with stage III colon cancer.34 In our study, we also observed no statistically significant association between high-fat dairy intake and risk of recurrence when assessing intake in quartiles (HRQ4 vs Q1: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.91–1.75), but we did detect a statistically significant association with risk of recurrence when assessing continuous intake (HRper 100 g/day: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.06–1.31, p for overall association: .008, Table 2, Figure 2B). Possibly, the difference in saturated fatty acid content among quartiles of high-fat dairy intake is too low to detect an association with risk of recurrence. Furthermore, the abundance of long-chain saturated fatty acids in high-fat dairy may form insoluble complexes with calcium that are excreted in the faeces,35-37 preventing calcium from performing its hypothesised protective action. The calcium-soap forming capacity and inhibition of calcium absorption were observed to be most prominent for long-chain saturated fatty acids,35, 38 which is the predominant fat source in milk.39 In humans, a meta-analysis of different randomised controlled trials also demonstrated that short-term dietary fortification of calcium increases faecal fat content.40 In conclusion, saturated fatty acids in high-fat dairy, at a certain threshold, may be associated with an increased risk of recurrence, possibly by preventing the calcium from performing its protective action.

Nevertheless, our results for low-fat dairy did not change or were even slightly stronger when adjusted for calcium intake from dairy sources (total study population: HRQ4 vs Q1: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.36–0.77), implying that calcium is at least not the only component in dairy responsible for its relation to risk of recurrence in CRC. Different dairy products have also been described to influence the microbiota composition in the gut.22 Drinking buttermilk has been associated with an increased microbial diversity, and specifically with the presence of the industrial fermentation-related species Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactococcus lactis, whereas drinking whole milk has been associated with a decreased diversity.22 Loss of microbial diversity has been associated with an increased risk of chronic inflammatory diseases,41, 42 and may also be involved in CRC progression.43 To increase our understanding of how low- and high-fat dairy influence risk of CRC recurrence, future research could study the calcium-related pathways and the extent to which calcium soaps are formed in people with CRC upon low- and high-fat dairy consumption.

Inherent to the lack of consensus in literature on how dairy components influence neoplastic growth in CRC, we can only speculate about the biological mechanisms underlying our sex- and tumour location-specific findings. In subgroup analyses, we observed that low-fat dairy was associated with a reduced risk of CRC recurrence in men, whereas this association appeared weaker in women. Previous studies have demonstrated associations between dairy or calcium from dairy and CRC-specific mortality to be more prominent in men than in women.7, 12 A possible explanation for these sex-specific findings is that calcium absorption has been observed to decrease with age, especially after menopause.44, 45 As the majority of women included in our study was at a reasonable age to be peri- or post-menopausal upon inclusion (median age: 65 [IQR: 59–71] years),46 a decreased calcium uptake in post-menopausal women could hypothetically explain why the association between low-fat dairy and risk of recurrence was less pronounced in women than in men. Our sample size did not allow for further stratification by calcium supplement use in women.

Furthermore, a higher intake of high-fat dairy seemed to be associated with an increased risk of recurrence in participants with colon cancer, but not in those with rectal cancer. Colon and rectal cancer differ in, among other aspects, genetic and molecular characteristics, oncogenesis, treatment, and possibly also risk factors for recurrence.9, 13 Besides, as proximal and distal colon cancer also differ in terms of etiological and molecular characteristics,47 it would be interesting to study the association between high-fat dairy intake and risk of recurrence in proximal and distal colon cancer separately. Although we have merged two datasets of relatively large cohort studies in CRC cases, our sample size did not allow for such analyses. Future investigations should confirm whether high-fat dairy is associated with an increased risk of colon cancer recurrence, and not rectal cancer, if possible further classified into proximal colon and distal colon cancer.

A strength of the current study is the availability of CRC recurrence data, which was retrieved in a standardised manner by specialised data managers from an experienced institute. A recurrence is a direct indicator of neoplastic growth and a common fear of cancer survivors,48 and therefore a highly relevant outcome measure. Another strength of this study is its relatively large sample size, that was achieved by merging the datasets of two large prospective cohort studies with similar methods and even identical questionnaires. This enabled us to follow up on previous findings and study associations between dairy and risk of recurrence in subgroups of sex, primary tumour location, and disease stage. Nevertheless, our sample size did not allow for stratification by age, or for further stratification by menopausal status or calcium supplement use in women, which would have been interesting to investigate potential sex-specificity of the association between low-fat dairy and risk of CRC recurrence. Furthermore, a limitation of the current study is that even though the extensive, 204-item FFQ we used has been successfully validated for fats, cholesterol, vitamin B12 and folate,27, 49 it has not been specifically validated for dairy. However, previous studies have demonstrated that FFQs in general can capture dairy intake reasonably well.50-52

In conclusion, our findings imply that dietary advice regarding low-fat dairy intake may be especially important in men with CRC, and that dietary advice regarding high-fat dairy intake may be specifically important in people with colon cancer. Understanding how dairy intake relates to the risk of recurrence in specific subgroups of individuals with CRC may prove especially relevant in a world that is transitioning towards more plant-based diets,53, 54 and where the number of CRC survivors is increasing.55 We recommend future studies investigating associations between dairy intake and CRC prognosis to split total dairy into low- and high-fat dairy, as these seem to be associated to CRC prognosis in opposite directions. Future observational and ultimately intervention studies should confirm our findings before they can be translated to more personalised dietary guidelines for people with CRC who aim to improve their disease prognosis.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anne-Sophie van Lanen: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing-original draft. Dieuwertje E. Kok: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing-reviewing and editing. Evertine Wesselink: Investigation, Writing-reviewing and editing. Jeroen W. G. Derksen: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing-reviewing and editing. Anne M. May: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing-reviewing and editing. Karel C. Smit: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing-reviewing and editing. Miriam Koopman: Funding acquisition, Resources, Project administration, Writing-reviewing and editing. Johannes de Wilt: Resources, Writing-reviewing and editing. Ellen Kampman: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing-reviewing and editing. Fränzel J. B. van Duijnhoven: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing-reviewing and editing. The work reported in the paper has been performed by the authors, unless clearly specified in the text.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all participants of the COLON and PLCRC-PROTECT studies, the involved co-workers in the participating hospitals, and the investigators at Wageningen University & Research and University Medical Center Utrecht. Also, the authors would like to thank the registration team of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL) for the collection of data for the Netherlands Cancer Registry.

Members of COLON and PLCRC studies: Hester van Cruijsen (Department of Medical Oncology, Antonius Hospital, Sneek, The Netherlands), Jan Willem T. Dekker (Department of Surgery, Reinier de Graaf Hospital, Delft, The Netherlands), N. Tjarda van Heek (Department of Surgery, Hospital Gelderse Vallei, Ede, The Netherlands), Danny Houtsma (Department of Medical Oncology, Haga Hospital, Den Haag, The Netherlands), Ewout A. Kouwenhoven (Department of Surgery, Hospital Group Twente ZGT, Almelo, The Netherlands), Ron C. Rietbroek (Department of Medical Oncology, Rode Kruis Hospital, Beverwijk, The Netherlands), Ruud W.M. Schrauwen (Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Bernhoven Hospital, Uden, The Netherlands), Dirkje W. Sommeijer (Department of Internal Medicine, Flevo Hospital, Almere, The Netherlands), Dirk J.A. Sonneveld (Department of Surgery, Dijklander Hospital, Hoorn, The Netherlands), Frederiek Terheggen (Department of Medical Oncology, Bravis Hospital, Roosendaal, The Netherlands).

FUNDING INFORMATION

The COLON study was supported by Wereld Kanker Onderzoek Fonds (WKOF) & World Cancer Research Fund International (WCRF International) as well as by funding (2014/1179, IIG_FULL_2021_022 and IIG_FULL_2021_023) obtained from the Wereld Kanker Onderzoek Fonds (WKOF) as part of the World Cancer Research Fund International grant programme; Alpe d'Huzes/Dutch Cancer Society (UM 2012-5653, UW 2013-5927, UW 2015-7946); ERA-NET on Translational Cancer Research (TRANSCAN: Dutch Cancer Society (UW2013-6397, UW2014-6877) and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Netherlands) and the Regio Deal Foodvalley (162135). The Prospective Dutch Colorectal Cancer (PLCRC) cohort is an initiative of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG), and is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society; Stand Up to Cancer; ZonMw; Health Holland; Maag Lever Darm Stichting; Lilly (unrestricted grant); Merck (unrestricted grant); Bristol-Myers Squibb (unrestricted grant); Bayer (unrestricted grant); Servier (unrestricted grant); Province of Utrecht, the Netherlands; and the Regio Deal Foodvalley (162135). The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

MK reports having an advisory role for Eisai, Nordic Farma, Merck-Serono, Pierre Fabre, and Servier, and to have received institutional scientific grants from Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Personal Genome Diagnostics (PGDx), Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sirtex, and Servier. MK is PI of the international cohort study PROMETCO with Servier as sponsor. MK is chair of the ESMO RWD-DH working group, co-chair of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG), PI of PLCRC (national observational cohort study), and is involved in several clinical trials as PI or co-investigator in CRC. The other co-authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Both studies were approved by a medical ethics committee (COLON: region Arnhem-Nijmegen, 2009-349, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03191110; PLCRC-PROTECT: University Medical Center Utrecht, 15-770/C, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02070146), and all study participants provided written informed consent.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

For the COLON study, requests for data can be sent to Dr. Fränzel J. B. van Duijnhoven, Division of Human Nutrition and Health, Wageningen University & Research, Netherlands (e-mail: [email protected]). For the PLCRC-PROTECT study, access to cohort resources for future collaborative research projects may be requested through the Scientific Committee of PLCRC (email: [email protected]) that reviews all research projects for approval. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request.