ZMYND11-related syndromic intellectual disability: 16 patients delineating and expanding the phenotypic spectrum

Abstract

Pathogenic variants in ZMYND11, which acts as a transcriptional repressor, have been associated with intellectual disability, behavioral abnormalities, and seizures. Only 11 affected individuals have been reported to date, and the phenotype associated with pathogenic variants in this gene have not been fully defined. Here, we present 16 additional patients with predicted pathogenic heterozygous variants in including four individuals from the same family, to further delineate and expand the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of ZMYND11-related syndromic intellectual disability. The associated phenotype includes developmental delay, particularly affecting speech, mild-moderate intellectual disability, significant behavioral abnormalities, seizures, and hypotonia. There are subtle shared dysmorphic features, including prominent eyelashes and eyebrows, a depressed nasal bridge with bulbous nasal tip, anteverted nares, thin vermilion of the upper lip, and wide mouth. Novel features include brachydactyly and tooth enamel hypoplasia. Most identified variants are likely to result in premature truncation and/or nonsense-mediated decay. Two ZMYND11 variants located in the final exon—p.(Gln586*) (likely escaping nonsense-mediated decay) and p.(Cys574Arg)—are predicted to disrupt the MYND-type zinc-finger motif and likely interfere with binding to its interaction partners. Hence, the homogeneous phenotype likely results from a common mechanism of loss-of-function.

1 INTRODUCTION

The chromosome 10p15.3 microdeletion syndrome is characterized by developmental delay (DD) and intellectual disability (ID), craniofacial dysmorphism, behavioral abnormalities, hypotonia, and seizures (DeScipio et al., 2013). Haploinsufficiency of ZMYND11 (NCBI Gene ID: 10771) is believed to account for many of the features associated with chromosome 10p15.3 microdeletion (Tumiene et al., 2017). ZMYND11 has been shown to act as a transcriptional repressor by inhibiting the elongation phase of RNA polymerase II by recognizing the histone modification present in transcribed regions, specifically H3K36 trimethylation (Wen et al., 2014).

In support of the critical role of ZMYND11 in the chromosome 10p15.3 microdeletion syndrome, patients with de novo truncating variants in ZMYND11 have a similar phenotype, including ID, seizures, and behavioral issues (Coe et al., 2014; Popp et al., 2017). In addition, missense variants in this gene have also been associated with ID and seizures, although there is a more severe phenotype in patients with specific variants, which may be related to a gain-of-function mechanism (Cobben et al., 2014; Moskowitz et al., 2016). A splice site variant has also been reported in a child with autism spectrum disorder (Iossifov et al., 2012). In total, 11 patients with pathogenic variants in ZMYND11 (MIM# 616083) have been reported to date (Aoi et al., 2019; Cobben et al., 2014; Coe et al., 2014; Iossifov et al., 2012; Moskowitz et al., 2016; Popp et al., 2017).

Here, we present 16 previously unreported individuals with pathogenic variants in ZMYND11, including four from the same family. We further delineate and expand the genotype–phenotype correlations and phenotypic spectrum of ZMYND11-related ID.

2 METHODS

All patients were ascertained after routine referral to their local Clinical Genetics service. Patients 1, 3, 5, and 8 were gathered through international collaboration using GeneMatcher (Sobreira, Schiettecatte, Valle, & Hamosh, 2016). Patients 2, 6, 7, 9, 11, and 12 were identified through the Wellcome Trust Deciphering Developmental Disorders study (Wright et al., 2015). Patients 13–15 were identified as affected relatives of Patient 12. Patients 4, 10, and 16 were identified through personal communication. Exome sequencing was performed on all probands, with a trio approach on Patients 1, 3, 5, 6, 9–12, and 16; and a duo approach on Patients 2, 4, 7, and 8, as DNA samples were only available from one parent. Sanger sequencing only was used to ascertain the presence of the familial variant in Patients 13–15, and all other patients had their ZMYND11 variant confirmed using this method. All sequence variants were described with reference to the ZMYND11 transcript NM_006624.5. All variants were classified according to the American College of Medical Genetics guidelines (Richards et al., 2015). Further information is available in the Supporting Information Data. Patient variants have been uploaded to either ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/), Global Variome shared LOVD http://www.lovd.nl, or DECIPHER (https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk). Informed consent was obtained for all subjects for inclusion in this study.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Molecular results

Sixteen individuals (including 13 probands and two additional children of one affected mother) had a predicted pathogenic variant in ZMYND11. Of these, eight were de novo, one was inherited by three sibs from their affected mother, one was paternally inherited, and three were of unknown inheritance. Ten variants were predicted to result in protein truncation, two were missense, and one affected a splice site (Table 1). None of the variants in this series were present in the gnomAD database (v2.1.1; Karczewski et al., 2019). Of the two missense variants, one was located in a zinc-finger domain (c.1720T>C; p.(Cys574Arg)), and the other was not in a known functional domain (c.1246G>A; p.(Glu416Lys)). Further information is available in the Supporting Information Data.

| Proposed pathogenic mechanism | Haploinsufficiency: NMD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total |

| DECIPHER ID | SGS 306759 | SGS 307296 | CAR 279594 | SMB 307553 | |||||||

| ZMYND11 variant | c.46C>T | c.117-2A>T | c.630C>G | c.705_708delTGAG | c.1089G>A | c.1129del | c.1315_1318del | c.1525_1526del | c.1531C>T | c.1572dup | |

| Predicted effect on protein | p.(Gln16*) | Splice acceptor variant | p.(Tyr210*) | p.(Glu236Lysfs*52) | p.(Trp363*) | p.(Ser377Profs*11) | p.(Thr440Argfs*3) | p.(Lys509Glufs*6) | p.(Gln511*) | p.(Asp525Glyfs*5) | |

| Inheritance | De novo | Unknown | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | Unknown | Unknown | Pat | De novo | |

| Pathogenicity (ACMG criteria) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PS2, PM2, PP3) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PS2, PM2, PP3) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PS2, PM2) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PS2, PM2, PP3) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PS2, PM2, PP3) | Likely pathogenic (PVS1, PM2) | Likely pathogenic (PVS1, PM2) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3) | Likely pathogenic (PM2, PVS1_S, PS2_M) | |

| Age reported | 3 y | 8 y | 5 y 10 mo | 8 y | 8 y | 4 y | 13 y 8 mo | 18 y | 8 y | 2 y 7 mo | |

| Gender | F | F | F | M | M | M | M | M | M | F | |

| Feeding problems | Yes | No | nd | Yes (NG supplementation) | nd | No | Yes (NG supplementation) | Yes | Yes | No | 5/8 (63%) |

| Dysmorphic | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 6/10 (60%) |

| Delayed development | Yes | nd | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9/9 (100%) |

| Gross motor delay | 2 y | 17 mo | 2 y | 2 y | 2 y | Cannot walk unaided 4 y | 22 mo | 18 mo | 2–2.5 y | Not yet achieved | 8/10 (80%) |

| Speech delay | Limited vocabulary, difficult to understand | nd | Short sentences at 4 y | 2 y | First words 3 y; 2-word phrases 3.5 y | Not yet achieved | 2 y; difficult to understand until 3 y | 4 y | 2–2.5 y | 2 y | 9/9 (100%) |

| ID | nd | Mild, mainstream school with extra help | Mild | Mild | Mild | Mild | Moderate | nd | Mild, mainstream school with extra help. Dyspraxia. | Moderate | 8/8 (100%) |

| Behavioral difficulties | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9/10 (90%) |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity/impulsivity | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 5/10 (50%) |

| Aggression/anger | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | 4/10(40%) |

| Autism/autistic traits | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | 2/10 (20%) |

| Hypotonia | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | 4/10 (40%) |

| Epilepsy | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 2/10 (20%) |

| Proposed pathogenic mechanism | Predicted to disrupt MYND zinc-finger domain | Missense | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | Total | 16 | Overall Total |

| DECIPHER ID | BWH 264849 | GSH 282655 | ||||||

| ZMYND11 variant | c.1720T>C | c.1756C>T | c.1756C>T | c.1756C>T | c.1756C>T | c.1246G>A | ||

| Predicted effect on protein | p.(Cys574Arg) | p.(Gln586*) | p.(Gln586*) | p.(Gln586*) | p.(Gln586*) | p.(Glu416Lys) | ||

| Inheritance | De novo | Mat | Mat | Mat | Unknown | De novo | ||

| Pathogenicity (ACMG criteria) | Likely pathogenic (PS2, PM2, PP3) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3) | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3) | Likely pathogenic (PS2, PM2) | ||

| Age reported | 15 y | 17 y | 22 y | 20 y | 47 y | 2 y 5 mo | ||

| Gender | M | M | F | F | F | M | ||

| Feeding problems | No | No | No | No | nd | 0/4 (0%) | Yes | 5/13 (38%) |

| Dysmorphic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 4/5 (80%) | Yes | 11/16 (69%) |

| Delayed development | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | nd | 4/4 (100%) | Yes | 14/14 (100%) |

| Gross motor delay | 13 mo | 2.5 y | 18 mo | 4 y | nd | 2/4 (50%) | Not yet achieved | 11/15 (73%) |

| Speech delay | 2–2.5 y | 4–5 y | First words around 4 y | First words around 4 y | nd | 4/4 (100%) | Not yet achieved | 13/13 (100%) |

| ID | Moderate ID, attends special school | Yes, attended special school, now in simple employment | Yes, attended special school, not able to take GCSE, volunteering activities in school, currently in college | Yes, attended special school, not able to take GCSE but currently working in retail | Yes, attended special school | 5/5 (100%) | nd | 13/13 (100%) |

| Behavioral difficulties | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 4/5 (80%) | Yes | 14/15 (93%) |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity/impulsivity | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | 3/5 (60%) | No | 8/16 (50%) |

| Aggression/anger | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 4/5 (80%) | No | 8/16 (50%) |

| Autism/autistic traits | Yes | No | No | No | No | 1/5 (20%) | nd | 3/15 (20%) |

| Hypotonia | No | No | No | No | No | 0/5 (0%) | Yes | 5/16 (31%) |

| Epilepsy | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes (as child) | 3/5 (50%) | No | 5/15 (33%) |

- Note: Totals include only those patients for whom the presence or absence of the feature is reported. Mutation nomenclature according to Human Genome Variation Society recommendations (http://varnomen.hgvs.org/). All variants were analyzed according to transcript NM_006624.5. American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics sequence interpretation criteria according to Richards et al. (2015).

- Abbreviations: ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics; F, female; GCSE, the general certificate of secondary education; ID, intellectual disability; M, male; nd, not defined.

3.2 Patient phenotypes

Phenotypic information for all patients is shown in Table 1. In-depth patient summaries are available in the Supporting Information Data (Supporting Information Patient Summaries). Prominent phenotypic features are detailed below. The denominators refer to the number of patients for whom the specific information is available.

Birth weight was at or above the 98th centile in three patients (3/14; 21%). Feeding problems (e.g., excess vomiting after feeds, bottle feeding requiring more than 1 hour), were present in 6/13 patients (46%). Most patients had normal growth parameters and head circumference.

Development was delayed in all patients (14/14; 100%). The median age at independent walking was 24 months (with an age range of 17 months to 4 years). Three patients remained unable to walk at the ages of two-and-a-half (for two individuals) and 4 years, respectively. Speech delay was prominent, with 14/14 (100%) affected. First words were achieved at a median age of two-and-a-half years (with age range of 2–4 years). Two patients were nonambulatory and had not achieved speech at two-and-a-half and 4 years age, respectively (2/14; 14%). All patients had mild to moderate ID (13/13; 100%).

Almost all patients had behavioral issues (14/16; 88%). These include attention deficit, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (8/16; 50%), aggressive behavior (8/16; 50%), and autism spectrum disorder or autistic traits (3/15; 20%). Neurological abnormalities were detected in 10/16 (63%); mostly hypotonia (5/16; 31%) and epilepsy (5/16; 31%).

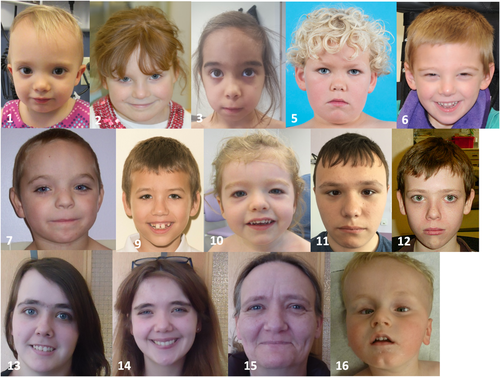

Photographs of patients in this series are shown in Figure 1. Dysmorphic facial features were judged to be present in 11/16 (69%). There were a number of shared facial features, including thick eyebrows, prominent eyelashes, a depressed nasal bridge with a bulbous nose, anteverted nares, and thin vermilion of the upper lip and wide mouth.

Photographs of patients in this series. Patient ages are as follows (y:- years; mo: months): 1–3 y, 2–8 y, 3–5 y 10 mo, 4–8 y, 6–4 y, 7–13 y 8 mo, 9–8 y, 10–2 y 7 mo, 11–15 y, 12–17 y, 13–22 y, 14–20 y, 15–47 y, 16–2.5 y. Note: Shared dysmorphic features (particularly in patients 1, 3–14, and 16) including prominent eyelashes and flattened nasal bridge with bulbous nasal tip

Patients 12–14 in this series inherited their ZMYND11 variant from their mother (Patient 15). All individuals in this family had special educational needs; two of the siblings are now in employment. The ZMYND11 variant found in Patient 9 was paternally inherited. Detailed phenotypic information is not available for the father.

4 DISCUSSION

Here, we present 16 new individuals with predicted pathogenic variants in ZMYND11. Comparison with all previously published patients allows further delineation of the phenotypic spectrum associated with mutations in this gene (Tables 2 and S1; Aoi et al., 2019; Cobben et al., 2014; Coe et al., 2014; Iossifov et al., 2012; Moskowitz et al., 2016; Popp et al., 2017).

| Proposed pathogenic mechanism | Haploinsufficiency: NMD | Disruption of MYND zinc-finger domain | Possible gain-of function | Total in all patients (including this series) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | Iossifov et al. | Coe et al. Nijmegen DNA05-04370 | Coe et al. Adelaide 3553 | Coe et al. Nijmegen DNA-017151 | Coe et al. Nijmegen DNA-002424 | Coe et al. Nijmegen DNA-013587 | Popp et al. | Aoi et al. | Coe et al. Adelaide 20124 | Total (where documented) | Cobben et al. | Moskowitz et al. | |

| ZMYND11 variant | c.1159-1G>A | c.1246_1247del | c.454_455insC | c.206dup | c.976C>T | c.561del | c.383del | c.1438del | c.1759_1761del | c.1798C > T | c.1262G>A | ||

| Predicted effect on protein | Splice variant | p.(Glu416Serfs*5) | p.(Asn152Thrfs*26) | p.(Thr70Asnfs*12) | p.(Gln326*) | p.(Met187Ilefs*19) | p.(Ser128Leufs*42) | p.(Asp480Thrfs*3) | p.(Gln587del) | p.(Arg600Trp) | p.(Ser421Asn) | ||

| Type of predicted variant effect | Splice variant | Frameshift | Frameshift | Frameshift | Nonsense | Frameshift | Frameshift | Frameshift | In-frame | Missense | Missense | ||

| Feeding problems | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | Yes | nd | Yes | 2/2 (100%) | Yes (NG supplementation) | Yes | 10/17 (59%) |

| Dysmorphic | nd | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | nd | Yes | Yes | 6/7 (86%) | Yes | Yes | 19/25 (66%) |

| Gross motor delay | nd | nd | Yes | Yes | nd | Yes | nd | nd | nd | 3/3 (100%) | Yes | Yes | 16/20 (80%) |

| Speech delay | nd | Nonverbal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | nd | nd | Yes | 6/6 (100%) | Yes | Nonverbal | 21/21 (100%) |

| ID | nd | Severe | nd | Mild | Mild | Mild | Severe | Yes | Mild | 7/7 (100%) | Severe | Severe | 21/21 (100%) |

| Behavioral difficulties | nd | nd | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/7 (100%) | nd | No | 21/24 (88%) |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity/impulsivity | nd | nd | nd | No | No | Yes | nd | No | nd | 1/4 (25%) | nd | Yes | 10/21 (48%) |

| Aggression/anger | nd | nd | nd | No | nd | Yes | Yes | No | nd | 2/4 (50%) | nd | No | 10/21 (48%) |

| Autism/autistic traits | Yes | Yes | nd | Yes | nd | No | nd | No | No | 3/6 (50%) | nd | No | 6/22 (27%) |

| Neurological abnormality | nd | Yes | Yes | No | nd | No | Yes | nd | Yes | 4/6 (67%) | Yes | Yes | 16/24 (67%) |

| Hypotonia | nd | Yes | No | Yes | nd | nd | Yes | nd | Yes | 4/5 (80%) | Yes | Yes | 11/23 (48%) |

| Epilepsy | nd | Yes | Yes | No | nd | No | Yes | nd | No | 3/6 (50%) | No | Yes | 9/24 (38%) |

- Note: Totals include only those patients for whom the presence or absence of the feature is reported. Mutation nomenclature according to Human Genome Variation Society recommendations (http://varnomen.hgvs.org/). All variants were analyzed according to transcript NM_006624.5. American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics sequence interpretation criteria according to Richards et al. (2015).

- Abbreviations: ID, intellectual disability; nd, not defined.

All patients (including our series) had DD, particularly affecting speech and ID. The severity of ID in this series is mild to moderate, but four patients have previously been described with severe ID (Cobben et al., 2014; Coe et al., 2014; Moskowitz et al., 2016; Popp et al., 2017). Behavioral issues are also a prominent feature both in our series and in those previously published (Coe et al., 2014; Popp et al., 2017), including aggression, attention deficit/hyperactivity, and autism/autistic traits. Therefore, this series provides further evidence that behavioral abnormalities are a significant part of the ZMYND11-associated phenotype. These behavioral problems may pose a substantial psychosocial burden, especially if the ID is mild. Hypotonia and epilepsy affect 48% and 39% of all patients, respectively (including our series). This enables us to indisputably establish hypotonia and epilepsy as part of the phenotype associated with this syndrome.

Dysmorphic features, particularly thick eyebrows, prominent eyelashes, and a bulbous nose, are present in the majority of patients (Figure 1). These are in line with the patients reported by Coe et al. (2014). These dysmorphisms may prove useful with regard to reverse phenotyping. Feeding difficulties were present in 59% of all patients (including our series), although only three patients required supplementary feeding.

Brachydactyly, seen in two patients in our series, is a possible novel feature. Interestingly, tooth enamel hypoplasia, present in one patient in our series, has previously been reported in another patient with a ZMYND11 variant (Coe et al., 2014), indicating this may be a rare and/or overlooked phenotypic feature, although formal dental assessment has not been documented for most patients.

In this series, three individuals inherited a predicted pathogenic ZMYND11 variant from their affected mother; another patient inherited the pathogenic variant from his father on whom detailed phenotypic information was lacking. Inheritance of a pathogenic ZMYND11 variant from an affected parent has been previously reported (Coe et al., 2014). Familial inheritance should, therefore, be considered in variant filtering and interpretation and reproductive counseling.

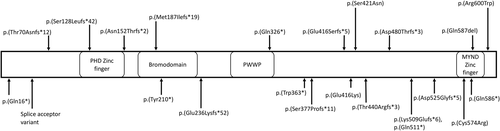

The majority of patients, including those in our series, have truncating variants, which are likely subject to nonsense-mediated decay, and hence, result in haploinsufficiency (Figure 2). Of note, the p.(Gln586*) variant in our series is located in the last exon and therefore may escape nonsense-mediated decay. The p.(Cys574Arg) variant is similarly located in the last exon. These variants may be expected to have a deleterious effect through disruption of the MNYD-type zinc-finger motif. This motif interacts with a number of intracellular partners, for example, the NCoR transcriptional corepressor (Masselink & Bernards, 2000), and amino acid variation within this motif has been shown to disrupt binding of these partners, resulting in reduced efficacy of ZMYND11-mediated transcriptional repression (Kateb et al., 2013; Masselink & Bernards, 2000). We suspect, therefore, that the two variants affecting the MYND-type zinc-finger motif domain in our series will at least result in a reduced function of the protein. The phenotype of these patients and a previously reported individual (Coe et al., 2014) with a p.(Gln587del) variant in this motif is not notably different to those patients harboring variants causing haploinsufficiency, supporting a loss-of-function mechanism. The p.(Glu416Lys) variant in this series is not in a functional domain. It has been classified as likely pathogenic given that it is de novo and not present in the gnomAD database; however further research is required to determine the effect of this variant.

ZMYND11 protein showing pathogenic variants in this series (below protein) and previously reported (above protein; Cobben et al., 2014; Coe et al., 2014; Iossifov et al., 2012; Moskowitz et al., 2016; Popp et al., 2017) (transcript NM_006624.5, Human Genome Build GRCh37.p13). Functional domains are labeled according to their location in the protein. The tandem PWWP (Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro)-Bromo domains function in recognizing H3K36 trimethylation

In contrast, two missense pathogenic variants have been reported in patients with notably different phenotypes to those in this series. The p.(Ser421Asn) variant resulted in a severe Angelman-like phenotype and the p.(Arg600Trp) variant caused distinct facial dysmorphism, moderate to severe ID, and short stature (Cobben et al., 2014; Moskowitz et al., 2016). Given these distinct phenotypes, it is possible that other mechanisms, including a gain-of-function, may be at play, but further research is required to characterize the effects of these specific variants.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We present a series of 16 patients with predicted pathogenic ZMYND11 variants, predicted to result in haploinsufficiency or reduced protein function, together with a review of the published literature, allowing further delineation of the associated phenotype. DD and ID, usually mild to moderate, are universally present. Behavioral issues are frequent, and hypotonia and seizures are common. Feeding difficulties occur but are usually mild. Subtle dysmorphism includes prominent eyelashes and eyebrows. Novel features include brachydactyly and tooth enamel hypoplasia. Our data will contribute to successful reverse phenotyping following genomic sequencing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the families involved for their permission to publish this study. The DDD study presents independent research commissioned by the Health Innovation Challenge Fund (Grant number HICF-1009-003). This study makes use of DECIPHER (http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk), which is funded by Wellcome. See Nature PMID: 25533962 or www.ddduk.org/access.html for full acknowledgment. Bert Callewaert is a Senior Clinical Investigator of the Research Foundation—Flanders.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Patient variants have been uploaded to either ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/), Global Variome shared LOVD http://www.lovd.nl, or DECIPHER (https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk). The accession numbers are: RCV000627377.1 (Clinvar), SGS 306759, SGS 307296, CAR 279594, SMB 307553, BWH 264849, GSH 282655 (DECIPHER), and via https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes/ZMYND11 (LOVD).