From Education to Action—The Impact of Hepatitis C Micro-Elimination Education on Healthcare Provider Confidence and Linkage to Care: A Quasi-Experimental Study

ABSTRACT

Background and Aim

Micro-elimination education can improve access to life-saving treatments for patients with hepatitis C, co-occurring mental health conditions, and alcohol and other drug use disorders. The Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is disproportionately prevalent among people with mental health conditions and alcohol and other drug issues, reducing their life expectancy. Although hepatitis C is a curable condition, this population frequently remains untested and untreated. Micro-elimination programs are necessary to enhance hepatitis C virus screening and treatment rates. This study aims to evaluate the impact of micro-elimination education on healthcare providers' confidence in identifying high-risk HCV populations, conducting HCV screenings and treatments, and managing comorbid substance use disorders. Additionally, it will assess referrals to a nurse-led HCV treatment clinic.

Methods

A quasi-experimental pre-posttest intervention design was used. The intervention was an education program targeted at HCV micro-elimination and linkage to care.

Results

Questionnaires were administered to (n = 101) healthcare providers to measure changes in confidence in screening and treating HCV in people with comorbid mental health conditions and alcohol and other drug disorders pre- and post-intervention. Pre-intervention, healthcare providers reported the highest confidence levels in treating mental health conditions. A significant increase in post-education confidence in screening and treating the HCV across all healthcare provider roles was observed (p < 0.05). Twenty-three referrals were received at the nurse-led hepatitis C virus treatment clinic, with the majority (n = 11) of referrals received from nurses.

Conclusion

This study underscores the significance of micro-elimination education programs in enhancing healthcare provider confidence in treating hepatitis C. Leveraging the mental health nursing workforce to connect high-risk populations with hepatitis C care will expand timely access to life-saving treatments and optimize healthcare outcomes. Targeted hepatitis C micro-elimination education will further accelerate progress toward the 2030 elimination goals, enhancing the overall well-being of vulnerable populations.

1 Introduction

Micro-elimination programs that focus on high-risk populations have been developed due to the World Health Organization (WHO) plan for eliminating the HCV by 2030 [1-3]. Micro-elimination is the targeted elimination of a specific infectious disease within defined populations [4]. Micro-elimination strategies for hepatitis C include targeted screening, access to treatment and support services, provision of education, and effective reduction of the disease's prevalence within these populations. Marginalized groups identified for micro-elimination are people who inject drugs (PWID), people with mental health conditions, and substance use disorders [1, 5-7]. The prevalence of hepatitis C remains high among PWID, and people with mental health conditions face a 5 to 10-fold increased risk of HCV infection compared to the general population [1, 4, 7].

There is now an urgent need to intensify elimination goals, as HCV diagnosis rates declined during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, causing a delay in screening and antiviral treatments [2, 5, 8, 9]. To meet the 2030 targets of 90% testing and 80% treatment coverage for HCV elimination, a significant simplification of care pathways is necessary to address access to HCV testing and treatment for the most vulnerable populations [8, 10, 11].

Hepatitis C is a life-threatening blood-borne virus, primarily transmitted through blood-to-blood contact, often linked to intravenous drug use. Direct-acting antiviral medicines (DAA) can cure more than 95% of persons with HCV infection, but access to diagnosis and treatment is low [12, 13]. Hepatitis C prevalence remains elevated within populations engaged in intravenous drug use [6], and comorbid mental health conditions and alcohol and other drug (AOD) use disorders. Both the WHO Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, 2016–2021 and the report Australian Recommendations for the Management of hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Consensus Statement 2022 identified several key priorities to achieve zero elimination targets [14, 15]. These priorities are educating healthcare providers (HCP), linkage to expert providers, and simplifying testing pathways incorporated into nurse-led care models [2, 14, 16].

The best linkage to care and treatment outcomes is evidenced by the health networks that offer onsite test and treatment models of care [17-19]. A nurse-led HCV treatment clinic model is available in the Perth South primary health network. A nurse practitioner works with GPs and other mental health services to improve physical health for people living with mental health conditions, substance use disorders, and hepatitis C [13, 20]. The nurse-led HCV treatment clinic offers a simplified HCV test and treatment strategy [2, 19]. Thus, offering HCV rapid screening, with DAA treatments in a single visit, facilitates engagement for prioritized micro populations [13, 20].

This study aims to evaluate micro-elimination education's impact on healthcare providers' confidence in identifying high-risk HCV populations, HCV screening and treatment, and comorbid substance use disorders. It will also measure referrals to a nurse-led HCV treatment clinic. It is hypothesized that micro-elimination education will improve the confidence in screening and treating HCV, including people with mental health conditions and AOD use disorders. The study will test two null hypotheses namely no significant difference in confidence levels pre- and post-education across healthcare provider roles and secondly, no difference in pre-education confidence levels among healthcare providers.

2 Methods

2.1 Design

A quasi-experimental pre-test-posttest design was used to evaluate the effectiveness of HCV micro-elimination education on participant confidence levels and the subsequent number of linkage to care referrals generated. This study followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) guidelines [21, 22]. (Supplementary File 1).

2.2 Study Setting and Recruitment

The micro-elimination education program was delivered through various forums, including general practitioner lunch meetings. We conducted our study between November 2022 and December 2023. Education was conducted at a tertiary hospital mental health journal club, a hepatitis C virus seminar, and a mental health nursing conference. The study was conducted within the Perth South Primary Health Network (PHN), with approximately 974,000 people living in high-density suburbs, metropolitan areas, and agricultural communities [23]. The region has a high burden of mental health issues, with 9.4% of the population experiencing anxiety and 9% experiencing depression, contributing to 12% of the total disease burden [23]. The region has a diverse population, with 20% of residents born in non-English speaking countries and 2.4% identifying as of Aboriginal descent [23]. Additionally, a significant proportion of the population (25%) is at risk of long-term harm from their alcohol consumption, and 0.6% have been diagnosed with hepatitis C [23, 24]. All participant attendance was voluntary. The educational sessions aimed to equip healthcare providers with the necessary knowledge and skills to identify and refer people with HCV.

2.3 Participant Inclusion Criteria

Healthcare providers who care for people with mental health conditions or alcohol and other substance disorders were invited to participate. Medicare bulk billing general practices and tertiary hospital services were included. The study was not limited to age or gender identity.

2.4 Intervention

The primary objective of micro-elimination education was to increase HCPs confidence in their clinical knowledge and in-depth understanding of HCV and its interplay with co-morbid mental health conditions and AOD. Education was also expected to empower HCPs with the knowledge and confidence to identify and refer patients to linkage to care. The educational program was delivered in a forty to 60-min presentation, which consisted of seven comprehensive sections designed to provide a thorough understanding of the subject matter as described in Table 1.

| Section | Topic | Key points | Expected outcomes | Research implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Epidemiology and prevalence. | Global distribution, regional trends, Australian modelling projections, and WHO micro-elimination targets [4, 6]. | Enhanced understanding of HCV epidemiology, identification of high-risk populations | Inform public health policy and target interventions. |

| 2 | Vulnerable populations. | Demographics, risk factors, mental health burden, intersection with HCV, and social impact [7, 23-26]. | Improved characterization of vulnerable populations, targeted interventions | Develop tailored prevention and treatment strategies. |

| 3 | Neurological manifestations. | HCV neuro-virulence, cognitive impairment, and neurological symptoms [27]. | Better understanding of HCV-related neurological effects, improved diagnosis | Investigate pathophysiology, develop neuroprotective therapies. |

| 4 | Diagnostic challenges | Diagnostic overshadowing, complex presentations, and screening strategies [28, 29]. | Enhanced diagnostic accuracy, improved treatment outcomes | Evaluate diagnostic tools, optimize clinical algorithms. |

| 5 | Direct-acting antivirals. | Efficacy, safety, treatment outcomes, and simplified therapeutic options [14, 28, 29]. | Increased knowledge of DAA treatment, improved treatment uptake, and prescribing. | Compare treatment regimens, investigate real-world effectiveness. |

| 6 | Point-of-care testing. | Test-and-treat models, linkage to care, and treatment initiation [2, 19, 30]. | Enhanced testing and treatment rates, improved patient outcomes, and models of care. | Evaluate POC testing strategies and optimize care pathways. |

| 7 | Clinical best practices. | Evidence-based recommendations, practical insights, HCV management guidelines [6, 14]. | Improved clinical practice, enhanced patient care, increased confidence in HCV management, and referral. | Inform clinical guidelines, promote best practices. |

2.5 Data Collection

Before the start of the education, all participants completed a pre-post micro-elimination education questionnaire. Questionnaires were a combination of paper-based or project postcards and a quick-response code. The questionnaire was a custom-designed instrument developed by the research team for the purpose of this study. Although not formally validated, the tool was reviewed and approved by the ‘Curtin University’ Human Ethics Committee Approval number: HRE2021-0476, to ensure compliance with ethical standards. The tool's development was informed by existing literature and expert consensus, but its psychometric properties were not established. Data was captured using Qualtrics survey software to collect responses [31]. Demographic data; gender, age in years, and role (years in role) were collected. A five-point Likert scale was used to gather experiences of treating people with HCV, mental health conditions, and AOD use disorders (patient numbers per year). Pre and post-visual analogue scales (0%–100%) were used to measure confidence levels assessed across seven domains. Finally, the number of client referrals received at a HCV treatment clinic was collected.

2.6 Data Analysis

All collected data from Qualtrics survey software [31] was exported into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 28 software for Windows [32]. Descriptive analysis was used to report the number of HCPs attending education meetings and people referred for screening. Descriptive statistics (mean and median) and dispersion measures (standard deviation and range) were used to describe the study's variables. Improvements in confidence post-education were determined using Wilcoxon Sign Ranked tests for non-parametric data and paired samples t-tests for normal distributed data. The Kruskal-Wallis test method is used to determine if there are significant differences between roles. Pairwise comparisons are reported using Dunn's non-parametric post-hoc test to examine variations in mean confidence levels across and within different roles within each group. Alpha was set at p < 0.05 level of significance.

2.7 Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was granted from Curtin University Human Ethics Approval - HRE2021-0476. The study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the National Health and Medical Officers Research Council of Australia (National Health and Medical Officers Research Council, 2019). Verbal/written consent was obtained from all participants. All research studies were carried out in compliance with the applicable COVID-19 government and relevant institution's restrictions.

3 Results

The total sample size was (n = 101), consisting of 55 female and 46 male participants, with a mean age of 43.73 (SD 2.66) years. The respondents' roles in the practice are diverse, with the largest proportion being nurses (40.6%, n = 41), followed by GPs (24.8%, n = 25). Four major groups of healthcare professionals were identified: allied health workers, medical officers, general practitioners, and mental health nurses.

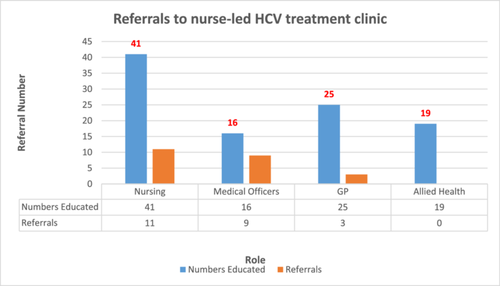

A total of (n = 25) GPs received education, and a total of (n = 23) people were referred to the nurse-led HCV treatment clinic post-intervention. These findings provide insights into the referral patterns based on the roles of healthcare professionals, indicating variations in the likelihood of individuals seeking further assistance from nurse-led HCV treatment clinics after receiving education from different roles (Figure 1)

Pre-education confidence in treating mental health conditions is highest in all groups: allied health (M = 48.37, SD = 21.99), medical officers (M = 74.37, SD = 19.47), GP (M = 69.24, SD = 13.22), and nursing (M = 62.12, SD = 25.20) (Table 2).

| Allied health | Medical officers | GP | Nursing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 19) | (n = 16) | (n = 25) | (n = 41) | |||||

| Please indicate your confidence: | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Screening people for HCV | 20.2 | 19.4 | 38.9 | 25.9 | 44.3 | 13.8 | 27.5 | 26.2 |

| Treating HCV | 24.4 | 24.8 | 42.5 | 27.8 | 45.4 | 13.1 | 31.5 | 28.6 |

| Treating HCV with direct-acting antiviral agents | 18.7 | 18.3 | 35.3 | 24.6 | 41.7 | 12.4 | 28.1 | 26.6 |

| Treating mental health conditions | 48.4 | 22.0 | 74.4 | 19.5 | 69.2 | 13.3 | 62.1 | 25.2 |

| Treating drug and alcohol use disorders. | 39.5 | 18.9 | 67.8 | 20.3 | 56.4 | 13.8 | 58.1 | 24.5 |

| Identifying people with mental health conditions who are at risk of HCV | 28.5 | 21.7 | 51.4 | 22.9 | 43.3 | 12.3 | 45.5 | 27.5 |

| Treating people with mental health conditions and co-occurring HCV with direct-acting antiviral agents | 23.4 | 19.2 | 43.4 | 19.92 | 43.5 | 11.58 | 35.8 | 26.3 |

Chi-square tests reveal significant differences (p < 0.05) in the numbers of healthcare practitioners who treat mental health conditions and AOD disorders. Table 3 highlights statistical differences in the number of HCV cases health professionals treat. Most nurses, allied health professionals, and Medical Officers practitioners treat 0–50 cases of HCV. In comparison, more than 50% of GPs treat > 51 cases of HCV annually, so they are more experienced in treating this condition. In addition, most GPs (92%) and 89% of allied health professionals treat > 51 people for mental health conditions within a year, compared to 63% of nurses and 62% of medical officers. This suggests that GPs and allied health professionals have more experience treating mental health conditions. Allied health professionals and GPs reported treating a high number (> 51 per year) of people with AOD issues (94.7% and 96%, respectively), while only 60% of nurses and 62.5% of medical officers treated > 51 of people with AOD issues.

| Total | X2 | df | Sig. (2-sided) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience HCV | 0–50 | > 51 | n | 14.07 | 3 | 0.002* | |

| Role in all groups | Allied health | 18 | 1 | 19 | |||

| Medical officers | 12 | 4 | 16 | ||||

| GP | 12 | 13 | 25 | ||||

| Nursing | 34 | 7 | 41 | ||||

| Total | 76 | 25 | 101 | ||||

| Experience mental health conditions | 0–50 | > 51 | n | 10.34 | 3 | 0.013* | |

| Role in all groups | Allied health | 2 | 17 | 19 | |||

| Medical officers | 6 | 10 | 16 | ||||

| GP | 2 | 23 | 25 | ||||

| Nursing | 15 | 26 | 41 | ||||

| Total | 25 | 76 | 101 | ||||

| Experience AOD | 0–50 | > 51 | n | 16.57 | 3 | < 0.001* | |

| Role in all groups | Allied health | 1 | 18 | 19 | |||

| Medical officers | 6 | 10 | 16 | ||||

| GP | 1 | 24 | 25 | ||||

| Nursing | 16 | 25 | 41 | ||||

| Total | 24 | 77 | 101 |

- * Significant p < 0.05 (2-sided), Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact Test.

Running Shapiro-Wilk tests and Quantile-Quantile plots on the differenced data, data sets with significant p values, and the alternative hypothesis that the data is not normally distributed was accepted. Therefore, a non-parametric test was selected.

A mix of paired sample t-tests for normally distribution and Wilcoxon Sign Ranked tests for non-parametric data was used when comparing pre-test and posttest scores from the same group. Using Hommel's adjustment, p values have been adjusted for spurious significant p values across roles. Significant p values at 0.05 level have been highlighted; the alternative hypothesis is that the central tendency of the difference is greater than zero. The only nonsignificant result was for treating mental health conditions for GPs (Table 4).

| Allied health (n = 19) | Medical (n = 16) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Statistic | df | p | d | Mean (SD) | Statistic | df | p | d | |

| Screening people for HCV | 26.6 (16.0) | 7.25 | 18 | < 0.01a | 1.66 | 28.1 (26.4) | 4.26 | 15 | < 0.01a | 1.06 |

| Treating HCV | 24.1 (17.5) | 5.99 | 18 | < 0.01a | 1.38 | 22.5 (27.8) | 118.5 | 15 | 0.00485b | 1.18 |

| Treating HCV with DAA | 28.7 (17.2) | 7.26 | 18 | < 0.01a | 1.66 | 28.4 (24.5) | 122.5 | 15 | 0.00261b | 1.47 |

| Treating mental health conditions | 15.1 (11.9) | 5.44 | 18 | < 0.01a | 1.27 | 7.3 (20.9) | 93 | 15 | 0.0324b | 0.309 |

| Treating AOD | 19.3 (15.6) | 5.37 | 18 | < 0.01a | 1.23 | 11.2 (19.1) | 2.31 | 15 | 0.0167a | 0.597 |

| Identifying people with mental health conditions who are at risk of HCV | 27.2 (25.6) | 4.62 | 18 | < 0.01a | 1.06 | 21.1 (17.8) | 126.5 | 15 | 0.0013b | 0.871 |

| Treating people with mental health conditions and co-occurring HCV with DAA | 32.6 (25.2) | 5.63 | 18 | < 0.01a | 1.29 | 22.6 (17.9) | 126.5 | 15 | 0.00135b | 1.31 |

| GP (n = 25) | Nursing (n = 41) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | Statistic | df | p | d | Mean (SD) | Statistic | df | p | d | |

| Screening people for HCV | 11.3 (11.9) | 315.5 | 24 | < 0.01b | 0.82 | 29.5 (23.1) | 723.5 | 40 | < 0.01b | 0.8 |

| Treating HCV | 9.5 (8.4) | 5.65 | 24 | < 0.01a | 1.13 | 27.9 (23.7) | 7.55 | 40 | < 0.01a | 1.18 |

| Treating HCV with DAA | 13.4 (7.5) | 8.86 | 24 | < 0.01a | 1.77 | 32.5 (22.1) | 9.41 | 40 | < 0.01a | 1.47 |

| Treating mental health conditions | 1.1 (10.6) | 0.527 | 24 | 0.302 | — | 4.3 (21.9) | 525.5 | 40 | < 0.01b | 0.309 |

| Treating AOD | 8.5 (9.4) | 4.54 | 24 | < 0.01a | 0.91 | 10.0 (17.5) | 656 | 40 | < 0.01b | 0.597 |

| Identifying people with mental health conditions who are at risk of HCV | 13.5 (7.0) | 9.69 | 24 | < 0.01a | 0.76 | 21.9 (25.2) | 5.58 | 40 | < 0.01a | 0.871 |

| Treating people with mental health conditions and co-occurring HCV with DAA | 10.4 (7.9) | 6.58 | 24 | < 0.01a | 0.32 | 28.5 (21.7) | 8.4 | 40 | < 0.01a | 1.31 |

- Note: Significance p < 0.05. Medium effect size: Cohens d = 0.5, Large effect size: Cohens d = 0.8. SD = Standard deviation.

- a Paired sample t-test.

- b Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test statistic (W).

The Kruskal-Wallis test is a nonparametric method for comparing the medians of three or more groups of independent samples to determine whether a statistically significant difference exists between them. Kruskal-Wallis test is an omnibus test as it determines if there are significant differences between three or more groups but does not specify which pairs of groups differ. All variables are highly significant at 0.05 level (Table 5).

| Variable | Chi-squared | df | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening people for HCV | 15.073 | 3 | < 0.01* |

| Treating HCV | 12.847 | 3 | < 0.005* |

| Treating HCV with DAA | 19.119 | 3 | < 0.001* |

| Treating mental health conditions | 13.61 | 3 | < 0.001* |

| Treating AOD | 8.49 | 3 | 0.020* |

| Identifying people with mental health conditions who are at risk of HCV | 8.384 | 3 | 0.021* |

| Treating people with mental health conditions and co-occurring HCV with DAA | 20.922 | 3 | < 0.001* |

- Note: Kruskal-Wallis Test.

- * Significance p < 0.05.

Pairwise comparisons of post-education changes in the confidence of roles are reported using Dunn's test. Dunn's test is a non-parametric statistical post-hoc test and is used after a significant Kruskal-Wallis test to determine which specific pairs of groups are significantly different. p-value adjustments have been made using the Holm-Bonferroni method, with significant p-values after adjustment. The Holm-Bonferroni method is a statistical technique used to counteract the problem of multiple comparisons (Table 6).

| Screening people for HCV | Z value | p unadjusted | p adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP-allied health | 2.776 | 0.005 | 0.021* |

| Allied health-medical officers | −0.414 | 0.678 | 1 |

| GP-medical officers | −3.079 | 0.002 | 0.01* |

| Allied health-nursing | −0.096 | 0.923 | 0.923 |

| GP-nursing | −3.435 | 0.0005 | 0.003* |

| Nursing-medical officers | 0.387 | 0.698 | 1 |

| Treating HCV | Z value | p unadjusted | p adjusted |

| GP-allied health | 2.495 | 0.012 | 0.05* |

| Allied health-medical officers | −0.278 | 0.78 | 1 |

| GP-medical officers | −2.667 | 0.007 | 0.038* |

| Allied health-nursing | −0.291 | 0.77 | 1 |

| GP-nursing | −3.311 | 0.0009 | 0.005* |

| Nursing-medical officers | 0.046 | 0.963 | 0.963 |

| Treating HCV with DAA | Z value | p unadjusted | p adjusted |

| GP-allied health | 3.114 | 0.0001 | 0.007* |

| Allied health-medical officers | −0.31 | 0.756 | 1 |

| GP-medical officers | −3.289 | 0.001 | 0.005* |

| Allied health-nursing | −0.236 | 0.813 | 1 |

| GP-nursing | −3.993 | 0.00006 | 0.003* |

| Nursing-medical officers | 0.134 | 0.892 | 0.892 |

| Treating mental health conditions | Z value | p unadjusted | p adjusted |

| GP-allied health | 3.667 | 0.0002 | 0.001* |

| Allied health-medical officers | 1.523 | 0.127 | 0.255 |

| GP-medical officers | −1.871 | 0.061 | 0.183 |

| Allied health-nursing | 2.157 | 0.03 | 0.154 |

| GP-nursing | −2.039 | 0.041 | 0.165 |

| Nursing-medical officers | 0.277 | 0.783 | 0.781 |

| Treating AOD | Z value | p unadjusted | p adjusted |

| GP-allied health | 2.811 | 0.004 | 0.029* |

| Allied health-medical officers | 1.417 | 0.156 | 0.625 |

| GP-medical officers | −1.17 | 0.241 | 0.725 |

| Allied health-nursing | 2.31 | 0.02 | 0.104 |

| GP-nursing | −0.845 | 0.397 | 0.795 |

| Nursing-medical officers | 0.543 | 0.587 | 0.587 |

| Identifying people with mental health conditions who are at risk of HCV | Z value | p unadjusted | p adjusted |

| GP-allied health | 2.682 | 0.007 | 0.043* |

| Allied health-medical officers | 0.692 | 0.488 | 0.977 |

| GP-medical officers | −1.816 | 0.069 | 0.277 |

| Allied health-nursing | 0.898 | 0.368 | 1 |

| GP-nursing | −2.234 | 0.025 | 0.127 |

| Nursing-medical officers | 0.048 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Treating people with mental health conditions and co-occurring HCV with DAA | Z value | p unadjusted | p adjusted |

| GP-allied health | 4.06 | 0.00004 | 0.0002* |

| Allied health-medical officers | 1.222 | 0.221 | 0.664 |

| GP-medical officers | −2.564 | 0.01 | 0.041* |

| Allied health-nursing | 0.895 | 0.37 | 0.74 |

| GP-nursing | −3.891 | 0.00009 | 0.0004* |

| Nursing-medical officers | −0.564 | 0.572 | 0.572 |

- Note: Significance values were adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni method correction for multiple tests.

- * Significance p < 0.05.

4 Discussion

This study evaluates micro-elimination education's effectiveness in enhancing healthcare professionals' confidence and knowledge in identifying high-risk HCV populations, screening, and treatment. It also measures the impact of education on referral rates to a nurse-led HCV clinic. The results demonstrate that micro-elimination education improves healthcare professionals' confidence in HCV screening, treatment with DAAs, and managing co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders, ultimately increasing access to care and treatment for those affected by HCV. This study provides compelling evidence that supports our hypothesis. This confidence boost facilitates earlier diagnosis, screening, and treatment, reduces liver disease progression and transmission, and ensures evidence-based DAA prescribing, maximizing cure rates. Additionally, it narrows the confidence gap between GPs and nurses, fostering collaborative care and enhancing comprehensive patient outcomes.

Contrary to our expectations, allied health professionals reported surprisingly high levels of experience in treating mental health conditions and substance abuse within the past year. This could be attributed to the small sample size, which might overrepresent clinical psychologists, social workers, and occupational therapists with extensive experience in managing mental health conditions [33]. Government initiatives have also made allied health mental health services more accessible and affordable [33]. However, despite their experience, allied health professionals didn't refer patients to a nurse-led clinic for HCV treatment. One possible reason is that some professionals might not consider HCV treatment their core business, resulting in low case loads [34]. Effective communication between allied health and primary care practitioners is crucial for delivering high-quality patient care and increasing referrals to nurse-led HCV treatment. Another contributing factor may be the need for more experience with HCV care, collaborative networking, and HCV knowledge among allied health professionals [35, 36] Furthermore, allied health professionals might prioritize mental health conditions over somatic physical health conditions, potentially overlooking HCV symptoms [29, 37-39].

Interestingly, one study found that dietitians were the most accessed allied health clinicians for people with liver cirrhosis, while mental health and social work services were underutilized [40]. Specifically, only 14.1% of participants reported accessing a psychologist; mental health service usage was 17.7% [40]. This highlights the need for increased awareness and collaboration among healthcare professionals to address the comprehensive needs of patients with mental health conditions and HCV.

Addressing the gaps in HCV knowledge, communication, and prioritization among allied health professionals is essential for improving patient outcomes and increasing referrals to HCV treatment. With approximately 200,000 registered allied health professionals in Australia, providing micro-elimination education to this workforce can significantly enhance HCV diagnosis and treatment [41]. This education can empower 33,000 psychologists, 2,800 mental health occupational therapists, and 2,900 accredited mental health social workers to identify at-risk individuals and link them to care [41, 42]. Additionally, leveraging lived experience workers' insights can improve HCV care linkage [42].

Healthcare professionals across all roles demonstrated high pre-education confidence in treating mental health conditions, indicating a general comfort level and self-assuredness. This confidence may stem from comprehensive education and training programs and exposure to mental health challenges in their professional practice [43]. The high prevalence of mental health issues in Australia likely contributes to this confidence. Almost half of all Australians (45.5%) experience mental health conditions in their lifetime, and one in five (20.0%) experience mental health conditions annually [44]. This aligns with national trends, where mental health issues are a significant concern [44].

General Practitioners are pivotal in HCV management. They are highly confident in HCV screening, treatment, and mental health management and are more likely to identify and treat individuals with HCV and mental health conditions. As the primary point of contact, GPs (approximately 32,200 in Australia) play a crucial role in addressing the HCV epidemic, especially for complex cases [45]. In addition, GPs play a critical role in managing mental health conditions. According to the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2022), GPs consistently report psychological issues, such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances, as the top three reasons for patient presentations [46]. This has increased from 61% in 2017% to 71% in 2022 [46]. General practitioners, and nurses often have extensive experience treating individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders [25, 26, 47, 48]. People with mental health conditions are more likely to use illicit drugs, with 58% of PWID experiencing depression [25, 26, 47]. Co-occurring disorders increase mortality rates and reduce life expectancy [48]. However, PWID face significant barriers to healthcare access, including stigma, social marginalization, and financial constraints, highlighting the need for tailored support and inclusive healthcare services [47].

The second aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of micro-elimination education in enhancing referrals to a nurse-led HCV clinic. Nurses were more likely to refer patients than GPs (Figure 1), highlighting their crucial role in identifying and referring patients with mental health and HCV-related disorders. Targeted education for nurses may improve patient outcomes [49]. Lower GP referrals may be due to alternative clinic referrals. Research shows that practitioner-level barriers persist in HCV treatment [50-52]. Australian GPs demonstrate suboptimal HCV knowledge, with 72% referring patients to specialists and 55% uncertain about treating individuals who inject drugs, emphasizing the need for enhanced education and guidance [52].

General Practitioners face challenges in treating PWID and managing HCV cases, with some reluctant to treat PWID or consider HCV outside their scope [50, 52]. Workload pressure and limited time for initial patient assessments exacerbate these issues, leading to lower referral rates, overlooked intravenous drug use, and diagnostic overshadowing [12, 27-29, 37, 52]. Targeted education on HCV linkage to care referral sources can enhance GP care for micro-priority populations, addressing these gaps and improving patient outcomes [17].

Nursing professionals generated the highest number of referrals for HCV screening and care, likely due to their broad scope of practice involving direct patient care, health promotion, and care coordination [34]. Nurses' prolonged engagement and continuous patient interaction enable them to identify individual needs, convey vital health information, and foster trust and open communication, making patients more receptive to wellness program referrals [49, 53, 54]. Effective interdisciplinary collaboration with healthcare professionals and community resources is crucial for successful referrals [38, 55-57].

Nursing professionals are uniquely equipped to address co-occurring AOD and mental health conditions, providing comprehensive, holistic care that leads to effective treatment outcomes [58, 59]. Their extensive experience enables early identification, personalized treatment plans, and streamlined services, reducing relapse risk and healthcare costs [58]. By establishing trust and rapport, nursing professionals promote patient engagement, adherence to treatment, and optimized recovery prospects [58, 59]. This underscores the vital role of nursing professionals in addressing complex health needs, highlighting the need for support and resources to deliver exceptional care.

To eradicate hepatitis C as a public health concern, efforts should prioritize key populations such as PWID and people with mental health conditions [60, 61]. Improving health literacy and awareness among HCPs through training and mentorship is essential for task-sharing with nonspecialist doctors and nurses. This process requires targeted training, ongoing mentorship, and access to specialist support for complex cases. Training in mental health and substance risk assessments will enhance identification and linkage to care for those reluctant to access mainstream services. Raising awareness and ensuring non-stigmatizing care for vulnerable populations will promote prevention, harm reduction, treatment adherence, and post-cure management. People who remain untreated often have limited healthcare engagement and are considered “hard to reach” [55]. Micro-elimination efforts, simplified same-day testing, diagnosis, and access to HCV treatment can significantly improve treatment rates for those diagnosed with HCV [17, 55, 60]. These initiatives will also expand treatment access for co-morbid mental health and AOD disorders in this vulnerable population.

Chronic HCV infection can be cured, presenting a unique opportunity for elimination. Targeted interventions, noninvasive testing, and access to DAA can eradicate HCV. Tailored micro-elimination education and enhanced healthcare professionals' confidence, particularly in HCV and alcohol and other drugs. Enhanced awareness and understanding of diagnostic overshadowing also will have significant implications for people with mental health conditions. Thus, the mental health nurse workforce is crucial in HCV referral and care linkage for vulnerable populations.

The conclusions of our study are compelling, yet there are certain limitations worth mentioning. The COVID-19 pandemic affected the number of GP practice visits, with numerous appointment cancellations occurring. A limitation of this study is the lack of a control group. However, the pre-post design offset this limitation, which allowed for a robust analysis of within and between group changes. A strength of the study was the utilization of the TREND guidelines, which are developed to enhance the transparency and completeness of reporting for nonrandomized intervention studies [22]. The 22-item checklist improves the quality of data reporting, increases the rigor of nonrandomized methods, and ultimately serves as a valuable tool for intervention evaluation studies employing nonrandomized designs [21, 22].

Finally, nurses, the largest group of registered health professionals globally, play a vital role in identifying and caring for individuals with HCV and co-morbid mental health conditions [62]. With approximately 25,000 mental health nurses in Australia, their scope includes direct care, and health promotion [62, 63]. Nurses' established relationships with patients foster trust, encouraging open communication about risk behaviors and facilitating blood-borne virus screening [63]. Mental health-trained nurse practitioners specializing in HCV can significantly improve access to treatment services, providing comprehensive care through education, support, and interprofessional collaboration [25]. Enhanced awareness and early recognition of HCV symptoms can improve health outcomes and quality of life and contribute significantly to achieving the 2030 HCV elimination targets.

Author Contributions

Regan Preston: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Eric Lim: supervision, writing – review and editing. Shirley McGough: supervision, writing – review and editing. Glenn Boardman: data curation, formal analysis, methodology. Karen Heslop: formal analysis, methodology, supervision, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

There is a statistician on the author team. Glenn Boardman, Glenn. boardman@health. wa. gov. au. The authors have checked to make sure that our submission conforms as applicable to the Journal's statistical guidelines. The author(s) affirm that the methods used in the data analyses are suitably applied to their data within their study design and context, and the statistical findings have been implemented and interpreted correctly. The author(s) agrees to take responsibility for ensuring that the choice of statistical approach is appropriate and is conducted and interpreted correctly as a condition to submit to the Journal. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript [Regan Preston] had full access to all of the data in this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Open access publishing facilitated by Curtin University, as part of the Wiley - Curtin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.