The Kumagai Method Using the Pigeon Long Nipple for Dealing With Various Movements While Bottle Feeding Children With Cleft Lip And/or Palate: A Qualitative Descriptive Study

ABSTRACT

Background and Aims

Feeding poses a significant challenge for children with cleft lip and/or palate. The Kumagai method, a specialized approach for feeding these children, has been developed; its fundamental techniques have already been published. However, children often exhibit varied reactions to feeding, such as refusal and resistance. If not managed appropriately, these responses can hinder feeding progress. This study aimed to identify strategies for addressing different feeding-related movements in children with cleft lip and/or palate during bottle feeding.

Methods

In September 2022, five specialist nurses from a Japanese urban university, all trained in the Kumagai method—an experimental nursing procedure involving bottle feeding with a long-nipple bottle—participated in this descriptive study. Structured interviews were conducted to explore techniques for managing feeding-related movements, covering 14 scenarios that encompassed children's oral reactions and gross motor movements before, immediately before, and during feeding.

Results

The participants described their techniques for handling each scenario. Some strategies followed a predefined order of priority, while others were adapted based on the intensity of the child's movements. Additionally, some strategies were chosen according to the nurses' assessments of the child's needs.

Conclusions

The Kumagai method emphasizes observing a child's reactions and movements, interpreting their significance and applying appropriate handling strategies accordingly. These assessments and tailored interventions might help children develop a natural feeding posture, ultimately fostering their acceptance of and willingness to feed using a long-nipple bottle.

Summary

-

Feeding poses a major obstacle for children with cleft lip and/or palate (CLP).

-

The Kumagai method involves observing the child's reactions and movements, considering what these movements indicate, and developing strategies for handling the child accordingly.

-

These appropriate assessments and dealing strategies presented in the current study might help children with CLP develop a natural feeding posture and contribute to the child's acceptance of and willingness to be fed with a long nipple bottle.

1 Introduction

Feeding poses a major challenge for children with cleft lip and/or palate (CLP). CLP is one of the most common facial oral deformities [1]. Moderate or severe feeding difficulties have been reported in > 70% of children with CLP [2] owing to inadequate suctioning and nasal reflux, which in turn lead to insufficient feeding volume, inadequate weight gain, prolonged feeding time, and infant fatigue [3]. Since breastfeeding infants with CLP who cannot apply sufficient suction pressure is difficult, caregivers often rely on bottle feeding. In a Nigerian study, > 80% of 65 mothers of children with CLP initiated breastfeeding, but only < 20% could continue owing to infant's inability to be fed in this manner [4]. This inability to continue breastfeeding has been reported in many countries [5-9]; bottle feeding has become the factual means of oral feeding. Children with CLP have a passage leading from the oral cavity to the fragile part of the nasal septum. An ulceration is likely to occur when the nipple directly makes contact close to the nasal septum during bottle feeding [10]. Moreover, since each child with CLP experiences unique feeding difficulties, bottle-feeding techniques should be tailored to the needs of each child.

Despite recent survey studies on parents of children with CLP, difficulties with bottle feeding have persisted. Parents in Ghana [11] and Turkey [12] lack knowledge related to CLP, and their children face problems stemming from feeding or related to nutrition. Similarly, lack of parental access to medical advice and counseling for CLP has been reported in various other countries, including Japan [13], Thailand [14], the United States [15, 16], Nigeria [4], India [17], and Norway [6]. Parents in such environments experience high levels of stress, depression, and anxiety related to the child's feeding [8, 16, 18, 19]. Therefore, the feeding difficulties faced by children with CLP have attracted significant attention worldwide.

A recent article has published a strategy for feeding children with CLP, called the Kumagai method, which involves the use of the Pigeon bottle with a long nipple (Long Nipple) [20]. However, the paper reported the basic procedures of the Kumagai method for an immobile doll, rather than for a moving child. We present the differences between the previous paper and this present study in Table 1. During feeding, children often move in various ways to express refusal, resistance, or related habits; improvements in feeding patterns cannot be expected unless appropriate measures are taken to address these movements. Thus, this study aimed to identify strategies for dealing with the various movements of children with CLP regarding bottle feeding.

| Aspect | Basic Kumagai method ([20]) | Present study |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation setting | Assuming a baby who does not move | Assuming a real baby who moves in various ways |

| Focus of techniques | Basic Procedures demonstrated on an immobile training doll | Responsive techniques for undesirable movements |

| Feeding phase | Standard steps from initiating to ending of feeding | Phase-specific strategies based on observed infant behaviors |

| Presentation format | Narrative description with limited illustrations | Tables and figures with prioritized and categorized techniques |

| Intended contribution | Description and standardization of core bottle-feeding procedures | Practical knowledge about responding to real-time infant movements |

1.1 The Kumagai Method

Ms. Kumagai, director of the nursing department in a specialized dental hospital in Osaka, Japan, has been improving her feeding techniques for managing children with CLP for many years. Her technique series, called “the Kumagai method,” includes the basic procedures for using the Long Nipple [20].

The basic feeding posture includes “cuddling as if pulling the child toward oneself” and “holding the child straight in a slightly upright position.” The bottle is held with three fingers, while the nipple is pinched between the index and middle fingers. To insert the nipple, the nurse moves the bottle horizontally, lightly touches the lower lip with the nipple, then places it into the mouth so that it adheres to the lower lip and tongue. Milk is expressed by pinching the nipple with two fingers. The nipple is positioned at the center of the tongue. The time from touching the lower lip to pinching the nipple should be approximately 2 s. The timing of pinching is adjusted by observing the child's sucking, breathing, and swallowing [20].

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design

A qualitative descriptive design was used in the form of structured interviews. This study was conducted concurrently with another, which has been published [20]; the same participants were recruited in both studies. This study was conducted in accordance with qualitative research reporting guidelines, specifically the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ), ensuring transparency and reliability in participant selection, data collection, and analysis [21].

2.2 Setting

This study was conducted at a specialized dental hospital in Osaka, Japan, affiliated with an urban university. The CLP center in this hospital accepts patients from various regions of Japan. Ms. Kumagai works in that hospital, where she instructs and trains other nurses.

2.3 Participants

Five nurses in that hospital had mastered the Kumagai method. Therefore, those five nurses, including Ms. Kumagai, were recruited for participation in this study. No exclusion criteria for participation were set.

2.4 Data Collection

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews in September 2022. The participants were asked questions such as, “How do you respond when [the child exhibits undesirable movements]?” They provided verbal responses while demonstrating their techniques using a baby doll. The doll, Taa-kun (Medical Craft Corporation, Japan), is designed for lactation guidance, with its shape and weight modeled after a newborn. Therefore, the nurses estimated the simulated child's age to be under 3 months. To replicate the CLP condition, the doll's lips and palate were modified using a cutter.

The interviews were conducted by SU, a pediatric nursing researcher with experience in qualitative research and structured interviews, specializing in pediatric nursing. SU had no prior clinical relationship with the participants, minimizing potential bias in data collection. Reflexivity was maintained through regular discussions with co-authors to mitigate any personal preconceptions that could affect data interpretation.

The interview guide listed the child's undesirable movements exhibited before, immediately before, and during feeding. The child's movements are presented in Table 2. This list of child movements was reviewed by four experts before conducting this study. The experts included two nurses, Ms. Kumagai and Ms. Hirai, who was a subordinate of Ms. Kumagai and had mastered the Kumagai method, and two researchers (EN, SU) specialized in pediatric nursing but not having mastered the method. A video camera was placed in front of the participants at an approximate distance of 3 m, and a wearable camera was attached to them to record their viewpoint.

| Timing | Cases |

|---|---|

| Before feeding | Five gross motor movements: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Just before feeding | One oral reaction: |

|

|

| During feeding | Five gross motor movements: |

|

|

| Eight oral reactions: | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.5 Data Analyses

The researchers transcribed the verbatim data, incorporating participants' movements recorded in the video. Each participant was then contacted by mail to verify whether the transcription contained any errors or omissions. Since most of the verbatim data from participants remained consistent, we determined that data saturation had been reached.

Content analysis, which was employed to analyze the data, summarizes obtained data in terms of semantic code content without adding any interpretation while objectively examining the data [22]. One researcher (EN) extracted the codes of each technique in the transcript and categorized them. The researcher created a draft of the techniques for dealing with each movement.

To enhance the analysis validity, the draft was checked by two researchers (EN and SU). Furthermore, additional revisions were requested from two experts (YK and YH) regarding the validity of the techniques, prioritization, and detailed settings. A consensus was reached on content validity after eight rounds of discussions and revisions.

2.6 Ethical Considerations

The researcher explained the study outline to the participants and obtained their written consent. The consent form detailed the study's purpose and methods, data storage, research funding, and contact information. The participants were assured of their right to participate voluntarily or withdraw at any time, protection from potential harm, and privacy safeguards. To protect the participants' privacy, their faces in the recorded videos were blurred using a mosaic filter. Additionally, the collected data were secured with a password to prevent unauthorized access. All procedures involving infants in the present study were conducted using training dolls that were modified to simulate CLP. No real infants were involved in the study; therefore, parental consent was not required. This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of our institution (code: 22136-02).

3 Results

The five participants recruited in this study had 18–36 years of nursing experience. The mean duration of experience in caring for children with CLP using the Kumagai Method was 14.2 ± 9.37 years. All participants were female, with an average age of 46 ± 6.3 years. The average interview duration was 40.0 ± 10.6 min (range: 27.1–56.0 min).

The long nipple is used for infants with CLP who cannot feed from a Pigeon Squeezing Bottle. We use this long nipple when the child has no swallowing difficulties but is unable to apply pressure to the nipple due to weak sucking movements or a wide cleft. Reflex patterns vary with age, but since not all children develop at the same pace, we do not adjust our approach based on age. Instead, we focus on the child's movements and respond accordingly. The presence of an oral plate does not alter our feeding approach.

— Nurse D

| Category | Detailed cases |

|---|---|

| 1) Before or after oral surgery |

|

| 2) Having factors of feeding difficulty regarding CLP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3) Weak of feeding ability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

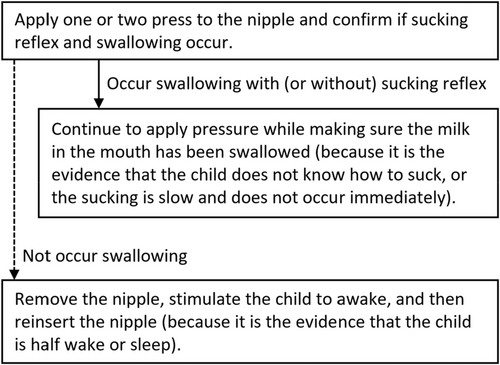

The dealing strategies for each undesirable movement at each period are shown in Figures 1-3 and Tables 4–7. Techniques for which priorities existed were indicated by number. In Figure 1, the solid lines indicate favorable situations in which feeding can continue, whereas the dotted lines indicate unfavorable situations in which further action is required. The child's movements might be compounded (e.g., when the child vomits together with the child arching his/her back). Even in such cases, the problem could be resolved by addressing each movement individually.

| Cases | Dealing strategies |

|---|---|

| When the child's upper extremities move violently |

|

|

|

|

|

| When the child's face tilts toward the breast of the nurse: | |

|

|

|

|

| When the child arches his/her back |

|

| When the child swings his/her face to the left or right |

|

|

|

|

- Note: The numbers indicate the order of priority.

| Cases | Dealing strategies |

|---|---|

| When the child's upper extremities move violently: | |

|

|

|

|

| When the child arches his/her back: | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| When the child swings the face to the left or right: | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cases | Dealing strategies |

|---|---|

| When the child pushes the nipple out with his/her tongue |

|

|

|

|

|

| When the child licks the nipple by moving the tongue up and down | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discontinue feeding (because it is evident that the child has reached satiety). |

| When the child moves the nipple toward the corner of the mouth with the tongue: | |

|

|

|

|

| When the child sucks with a collapsed nipple: | |

|

|

|

|

| When the force of the tongue strike up is too strong and the nipple is bent |

|

| When the child's sucking reflex is weak |

|

| When swallowing and gastrointestinal symptoms occur | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Note: The numbers indicate the order of priority.

3.1 Dealing With the Child's Gross Motor Movements Before Feeding

Before feeding, the child must be maintained in a stable position to enable drinking. If the child was violently crying, the nurse tried to handle the situation as priority by rocking the child from side to side or from up to down, walking around, patting on the child's hips, turning the child's body in the opposite direction, and attracting the child's attention through the senses of vision and hearing (drawing attention to sounds or lights, singing a song, showing a spinning washing machine, or showing a large picture).

I make this area (between the child's head and nurse's body) as narrow as possible and restrict the face so that it does not move. If this dealing strategy is done well (if the face does not move), I continue feeding. If the child's face continues to move, I place a small towel between the child's head and my body (Figure 4). If the nurse can feed from either the right or left side, re-holding the child with the opposite arm is also effective.

— Nurse B

3.2 Dealing With the Child's Mouth Just Before Feeding

First, I gently touch the lower lip using the nipple with the mouth closed and see if the mouth opens. If the mouth still does not open, I push the lower jaw down slightly and observe the inside of the mouth. If the child has a strong resistance to the nipple, the child will never open the mouth. But I have to feed, so I check to see if I can gently insert the nipple into the space between the palate and tongue while relaxing my hand holding the nipple. If it goes in, I flow out the milk. If you force the nipple into the mouth without checking the mouth, the nipple may stick to the underside of the tongue, and the upper and lower lips become entangled by inserting the nipple. That would be uncomfortable for the child and would cause strong feelings of rejection, so that is a bad practice that should be avoided.

— Nurse D

3.3 Dealing With the Child's Gross Motor Movements During Feeding

After nipple insertion, if the child exhibited rhythmic sucking with a closed mouth or if the tongue wrapped around the nipple, the nurses determined that the nipple had been accepted and continued feeding. However, some children displayed various reactions even after nipple insertion. Tables 5 and 6 and Figure 2 outline strategies for managing undesirable movements during this phase.

I pull it out and then I'll dandle the child.

— Nurse A

If the child starts crying when I put the nipple in, I often pull it out once. I then rock the child's body up and down and try to dandle the child.

— Nurse C

If the child cries even after the nipple is reinserted, I use the one-pressure method. This means that I pinch the nipple once, flow out milk, and pull it out immediately. This method is done when the child pushes out the nipple with the tongue or when the child moves violently and resists. If the child stops crying or cries less, I try the two-pressure method (pinch the nipple twice and pull it out immediately). Then, gradually increase the number of pinchings. If the child still cries violently, I stop feeding for a time and try to feed while keeping the child in a semi-awake state. If the child still moves, cries, or reacts in any way showing that the child does not want to be fed, I may have to decide to stop feeding.

— Nurse D

The nurses described how they attempted to maintain the nipple position consistency in the mouth even when the child's face was tilted or the child's body was arched. Additionally, they monitored the child's movements for signs that the child was reluctant to be fed or wanted to breathe (Figure 2, Table 6).

Regarding arching the child's back, if the arching is done gradually while sucking continuously, I assess that this situation implies that the child is in the habit of drinking while arching their back. When the child arches their back and returns immediately, I consider that the movement is intended for the child's breath and the child is accepting the nipple. However, if the child does not suckle rhythmically while arching, I assess that the child is not accepting the nipple, so I deal with the same situation as “the case of crying violently.

— Nurse D

If the child's face is tilted too much, I place a towel (between the child's head and my breast) or pull the child's body toward myself in tighter to make it difficult for the child's face to move. If there is staff around, I ask them to help the child's face turn forward naturally by such a playing drum.

— Nurse E

The child sometimes stops their suckle without disgust, turns the face outward, or arches the body back for a moment, and then returns to the right position. It is because the child wants to breathe, so I remove the nipple and let the child breathe. When the child's body comes back and the breath becomes stabilized, I reinsert the nipple.

— Nurse D

3.4 Dealing With the Child's Oral Reactions During Feeding

The rejecting action toward nipple is very important sign to observe the child's response. When the child pushes the nipple out with the tongue, I assess that the situation is a very rejecting reaction. When this happens, I always pull the nipple out, and I reinsert it again correctly. Repeating this is the only way. It is also helpful if I apply pressure earlier than the normal speed (one-pressure method). It will be to encourage the sucking reflex immediately and prevent the tongue from feeling the tip of the nipple by concentrating on feeding. When I use the one-pressure method, combining it with a quick knee-bending movement is more effective in briefly distracting the child from the nipple. The next rejecting reaction is to swing the tongue from side to side. In this case, I press the nipple a little to get milk into the mouth and observe if the sucking is encouraged. The reaction that the child moves the nipple to the corner of the mouth with their tongue is also rejection but not as strong. When this happens, the nipple should be gently moved back to the center of the tongue.

— Nurse D

I pull it out. I reinsert the nipple and set it in the right position. There is no problem if the child can drink by doing so. If the child still pushes out after several attempts, I would often leave for a little while.

— Nurse B

The case of not sucking in the child means that the child does not know how to suck, or when the sucking reflex does not occur immediately or is slow. In these cases, I apply pinching the nipple one or two times to induce the child's sucking. Then, the child swallows the milk in the mouth and begins to suck. When the sucking stops, I pinch the nipple again to induce swallowing and the child's sucking restarts. I continue this. This attempt of pinching for inducing suckling is different from the one- or two-pressure method. In the one- or two-pressure method, I remove the nipple immediately after pinching it. But in this case, I observe the child's swallowing while still placing the nipple in the mouth. Especially when the child licks the nipple, it indicates that they are not completely averse to it and feel somewhat comfortable with doubtfulness. Therefore, if I pull the nipple out repeatedly, the child's motivation will be broken.

— Nurse D

If the nipple was collapsed or bent in the mouth while feeding, this proved that the child actively wanted to be fed. Therefore, the nurses attempted to not compromise the child's desires in that situation.

When the child vomited too much milk, the feeding had to be interrupted; however, the nurses restarted feeding after the child had calmed down and tried to get the child to drink as much milk as possible.

I communicated my techniques that work for most children but not completely. Certainly, there are techniques that are implemented according to the situations. It almost works by using the techniques I explained, but sometimes it does not I am sure there are more things I could not explain this time.

— Nurse D

4 Discussion

When bottle-feeding, children often refuse feeding or exhibit distress [23]. Feeding problems are common in children with CLP [1, 2]. Previous research has shown that hunger cues in infants include bringing their hands to their mouths, crying, and sucking, while satiety cues include a decrease in sucking frequency, relaxation, and closing of the eyes [24]. Although observing infant movements is crucial for assessing feeding cues, accurately interpreting these cues requires specialized knowledge and experience. Therefore, this study presents strategies tailored to each child's movements. It highlights techniques used by nurses to manage undesirable infant movements before, immediately before, and during feeding. Following the guidance provided in these tables and figures, caregivers can better understand what to observe and how to determine the next appropriate action. The Kumagai method, which utilizes a long-nipple feeding technique, is a practical approach for managing undesirable infant movements and aims to correct feeding posture [20]. Addressing the child's gross motor movements and responding promptly to each reaction, caregivers can maximize the child's ability to feed. Clinical practice has reported improvements in the feeding of children with CLP using the Kumagai method. In cases of bilateral CLP with feeding difficulties, the method has been shown to improve both the volume and speed of milk intake [25]. Additionally, more than half of infants with CLP and nasal septum ulceration were able to consume the required amount of milk, with ulceration resolution, using the Kumagai method [26].

Various feeding bottles have been developed as a tool to improve feeding in children with CLP. The most commonly used bottles are the Pigeon feeding bottle for children with cleft palate in Japan [27] and Medela Special Needs Feeder and Dr. Brown's Specialty Feeding System in other countries [28]. However, no significant difference was observed in the child's feeding volume regardless of the bottle used [28]. Therefore, the key to improving infant feeding is not principally influenced by the bottle used but by the nurse's feeding technique in how it is used. Previous studies have reported the basic posture during feeding, when to squeeze the bottle during feeding, and some points to be observed [29-31]. However, those studies did not mention the undesirable movements of children. Our study presented several undesirable child movements and clarified how to deal with them. Specifically, identifying the child's response of the nipple rejection was significantly important for continuing and facilitating future feeding. Moreover, the one- or two-pressure methods for this rejection were unique and only possible with a Long Nipple. These findings potentially address the real difficulties and concerns associated with bottle feeding children with CLP worldwide.

Recently, videos of various feeding strategies by parents or medical providers are available on social media platforms. Although these are accessible and convenient for the audience, most of the video contents are inappropriate [32]. Moreover, actual parents of children with CLP show ineffective coping strategies [12]. The medical providers as informants also lack such skills [33] and wish to acquire them [27]. The present study presents practical knowledge because the specialists revealed skillful techniques that were developed in actual clinical practice. As a result, we hope that this technique will greatly contribute in clinical and educational settings worldwide, particularly for less experienced caregivers.

According to a recent study by Kucukguven et al. Kucukguven et al., [3], three of four patients used the feeding bottle; more than half of the children with CLP had to undergo nasal tube feeding. The current practice is to switch to tube feeding if the child cannot be bottle fed. Although tube feeding is excellent for preventing weight loss, it also has various adverse effects, including decreased taste and smell functions [34], oral aversion [35], and infection due to decreased salivation [36], suggesting the need for keeping the duration of tube feeding as short as possible [37]. The Kumagai method presented in our study does not require switching to tube feeding. This is a testament to the insistence on feeding from the oral route and capability of feeding sufficient amounts without switching to tube feeding. Adherence to the Kumagai method will increase the number of children with swallowing ability who can be fed orally.

This study has some limitations. Although we described various infant movements observed during feeding, certain motor behaviors might have been triggered by the nurses rather than being intrinsic to the infants. Additionally, strategies for managing undesirable behaviors cannot be judged solely based on whether they occur during feeding. Adjustments may be needed depending on the specific stage of feeding, such as whether the child is swallowing or still holding milk in their mouth. Although we identified techniques adaptable to many cases, they may not be applicable to all children. In practice, feeding difficulties are influenced by multiple factors, and approximately one-third of patients with CLP have coexisting congenital conditions [38]. Depending on individual feeding difficulties, nurses may prioritize different strategies or develop new approaches.

Although all participants in this study were nurses from the same institution, they had all mastered the Kumagai Method, and no major differences were observed in how they responded to various feeding difficulties. This consistency suggests the reliability and standardization of the method among trained users. Since the aim of this study was to clarify and describe the Kumagai Method itself—rather than to examine a variety of bottle-feeding strategies—we believe the study fulfilled its primary objective. Nevertheless, to further assess the broader applicability of the Kumagai Method and to explore whether other effective strategies are used in different clinical contexts, future studies should include participants from multiple institutions with diverse training backgrounds. In particular, larger and more diverse samples from various clinical settings are warranted to validate and expand the method's generalizability.

In addition to institutional diversity, the potential for broader dissemination also depends on how accessible the method is to less experienced providers. While this study focused on expert nurses trained in the Kumagai method, but its applicability by less experienced healthcare providers and caregivers should also be considered. Although basic techniques such as posture stabilization or nipple insertion may be teachable with structured guidance, adaptive responses to infant movements require more nuanced skills, potentially needing hands-on practice and supervision. Systematically organizing techniques in a phase-specific and logical manner, this present study provides a foundation framework that may help less experienced caregivers apply the Kumagai method without omissions or inconsistencies. Future studies should explore how caregivers or less experienced staff could adopt these techniques and identify potential challenges in real-world settings.

Another limitation is the challenge of fully conveying their own techniques through oral explanations. Therefore, acknowledging that the techniques developed by Ms. Kumagai might not have been comprehensively detailed, as she mentioned in the Results section, is important. The present findings should be carefully interpreted when applied in clinical settings. Moreover, beyond the techniques explicitly recognized by experts, there may be additional implicit knowledge that nurses apply unconsciously. Further studies should include direct observations of feeding instructions to assess the frequency of undesirable infant movements, the actual strategies nurses use to address them, and the effectiveness of these interventions. Additionally, this study did not recruit other experts in the field. Future research should include quantitative studies to determine whether the Kumagai method is unique or widely practiced and whether other effective strategies exist. Moreover, evaluating whether this method could be effectively implemented in different populations and clinical settings is necessary. Despite these limitations, we hope that the present study could provide foundational insights into guiding future research. Ultimately, these findings might contribute to the development of clinical guidelines or learning tools.

5 Conclusions

This study showcased expert techniques of dealing with undesirable movements of children with CLP during bottle feeding. The techniques included details that exceeded our predictions; they were selected after deep assessments. The Kumagai method involves observing the child's reactions and movements, considering what these movements indicate, and selecting strategies of handling the child accordingly. These appropriate assessments and dealing strategies may help children with CLP develop a natural feeding posture and may contribute to the child's acceptance of and willingness to be fed with a long nipple bottle.

Author Contributions

Eri Nagatomo: investigation, validation, writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Yukari Kumagai: validation, writing – review and editing. Yumi Hirai: validation, writing – review and editing. Shoko Miyauchi: investigation, validation, writing – review and editing. Takuro Inoue: investigation, validation, writing – review and editing. Qi An: investigation, writing – review and editing, supervision. Eri Tashiro: writing – review and editing. Junko Miyata: supervision, writing – review and editing. Shingo Ueki: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to all participants. This study was funded by the JSPS KAKENHI (grant number JP22K17504) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Tokyo, Japan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

E.N. had full access to all study data and assumes complete responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the analysis. E.N. affirms that this manuscript provides an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study; that no significant aspects have been omitted; and that any deviations from the original plan have been appropriately explained.