Views of Family Caregivers on Advance Care Planning in Advanced Dementia Care in Hong Kong: A Qualitative Thematic Content Analysis Study

ABSTRACT

Background

Advance care planning (ACP) can be useful for person-centered dementia care, but it is unfamiliar in Hong Kong. Without advanced discussion of care preferences, it can add stress to family caregivers in decision-making for future care and impact patients' quality of life. The study aimed to explore family caregivers' views on ACP as well as to understand their perceived outcomes.

Methods

This qualitative study involved 23 interviews with family caregivers who attended the ACP information talks. The interviews were transcribed and then coded using a thematic content analysis framework.

Results

Emerging themes include (1) receptive to ACP, (2) mixed emotions, (3) barriers to ACP, (4) family consensus in decision-making, and (5) benefits of ACP. Family caregivers were open to ACP when initiated by the healthcare team, particularly if patients had previously expressed a desire to forgo treatments, experienced prior crisis episodes, or had multiple hospital admissions. They found starting the conversation challenging, and local culture evaded the topic. Other barriers included the interpretation of filial expectation, building family consensus, and ACP knowledge gap. They needed to overcome internal emotional struggle and related barriers to progress the ACP process. The benefits of ACP included family cohesiveness, enhanced family communication, as well as better preparation for the patient's death, such as minimized unfinished business. For families that could not work through the barriers, the ACP process could become stagnant. Healthcare providers could play a pivotal role in facilitating ACP by addressing the ACP barriers.

Conclusions

Healthcare professionals can encourage ACP discussion in early dementia care. ACP can raise family caregivers' expectations in end-of-life care. The ACP outcome of quality care is more important than documentation of forgoing life-sustaining treatments or advance (medical) directives. Proper training for healthcare professionals is crucial for initiating and facilitating ACP as well as upholding quality end-of-life care.

1 Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) supports adults in understanding and sharing their personal values, goals, and preferences regarding future healthcare [1]. Discussing ACP with individuals suffering from advanced dementia is challenging due to its unique disease trajectory. Globally, over 55 million people are affected by dementia [2]. ACP has the potential to address patients' EOL care needs [3]. ACP is considered a vital component of person-centered care, yet it remains unfamiliar in Hong Kong. Without advance discussions, family caregivers remain unaware of patients' end-of-life (EOL) care preferences, often compromising their quality of life as the disease progresses [4].

Although ACP is new in Hong Kong, older adults and patients with progressive and life-limiting illnesses are beginning to embrace the concept. The recent gazettal of the Advance Decision on Life-sustaining Treatment Ordinance [5] with a prominence on the Advance Medical Directive (AMD) offers a timely opportunity to promote community education on ACP.

According to a 2020 survey conducted in the medical wards of Shatin Hospital, a convalescent and rehabilitation facility, up to one-third of admitted patients had severe chronic diseases and had been hospitalized more than twice in the past 6 months. Despite their high risk of deterioration and death within 1–2 years, most had not received structured information on ACP. Since 2021, family caregivers of patients with dementia (PWD) and serious medical conditions have been invited to attend structured ACP information sessions during patients' hospitalization. This period was considered a suitable time to initiate ACP discussions with family caregivers. The participants only learned about the formal concept of ACP and the pros and cons of various life-sustaining treatment (LST) options in the sessions.

In 2023, family caregivers who attended these ACP sessions were invited for interviews to gain deeper insights into the patient's journey in dementia care. For those who have completed the ACP process, the study aims to delve into their experiences during the discussion process and their perceived outcomes.

2 Methods/Design

This qualitative study, using thematic content analysis, involved individual telephone interviews with the family caregivers of elderly people with advanced dementia (PWAD). The recorded interviews were transcribed and coded using a thematic content analysis framework [6, 7]. The study design was a team effort to achieve the research objectives, involving an inter-disciplinary team.

2.1 The Setting and Participants

The ACP information sessions of 1.5 h were divided into two parts: the first, facilitated by a social worker, focused on exploring values and preferences. The second part, led by a geriatrician, covered end-of-life care, ACP, AMD, and LST. For ease of reference, a table highlighting the definition of terms can be found in Table 1 [8].

| Terms | Definition |

|---|---|

| Advance care planning (ACP) | A process for the patient to express preferences for future medical and personal care. A mentally competent and properly informed patient may make an AMD refusing LST, including DNACPR. The patient can assign a family member to be the key person for future consultation. The family members of a mentally incompetent adult or a minor, together with the healthcare team, may make plans for future medical or personal care, by consensus building according to the best interests of the patient, taking into account any expressed wish, preferences and values, and weighing benefits, risks, and burdens of available options. |

| Advance (medical) directive (AMD) | A patient-initiated document that contains instructions that if the person is mentally incapable of deciding on a life-sustaining treatment and the specified precondition of the instruction is met, the person is not to be subjected to any life-sustaining treatment specified in the instruction. |

| Do-not-attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) | A medical decision which refers to the elective decision not to perform CPR, made in advance, when cardiopulmonary arrest is anticipated, and CPR is against the wish of the patient or otherwise not in the best interests of the patient. |

| End-of-life (EOL) care | Care addressing the medical, social, emotional, and spiritual needs of people who are nearing the end of life. It may include a range of medical and social services, including disease-specific interventions as well as palliative care for those with advanced serious conditions who are near the end of life. |

| Life-sustaining treatment (LST) | Medical procedures that replace or support an essential bodily function. Life-sustaining treatments include cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), mechanical ventilation, artificial nutrition and hydration, dialysis, and certain other treatments. |

Initially, the talk sessions were held every 4–6 weeks in a hybrid format (both face-to-face and online) at a nearby university-affiliated facility during COVID-19 restrictions. Later, they transitioned to in-person sessions of 5–10 participants at the hospital. For those interested in further ACP discussions, follow-up meetings were arranged to complete the ACP process, including signing the ACP/AMD forms according to Hong Kong Hospital Authority guidelines [8]. The content of the ACP discussions included EOL care, LST, and AMD.

The inclusion criteria required participants to be family caregivers of PWD who attended the ACP talks. Exclusion criteria included individuals under 18, those with cognitive impairments or mental incapacity, and those unable to speak or comprehend Cantonese.

2.2 Interviews

Between March 2021 and April 2024, 28 talk sessions were held for 164 family caregivers of 117 patients. Follow-up calls were made reaching 124 family caregivers and successfully conducting 23 individual semi-structured interviews. At the time of the interviews, five families had completed the ACP documentation process and were all interviewed.

Interviews of family caregivers who did not proceed with the formal ACP documentation post-talk were conducted by three trained interviewers, resulting in 18 interviews. One researcher conducted interviews with the five families who completed the ACP process. These interviews took place between November 2023 and February 2024.

A total of 124 family caregivers provided feedback on the effectiveness and benefits of the ACP talks in aiding their understanding of ACP. A summary table of their feedback is available in the Supporting Information S1.

Family caregivers who had completed the ACP process further explored their experiences of the ACP process. Based on literature [9, 10] and clinical observations, a semi-structured interview guide was developed to meet the study's objectives.

2.3 Data Analysis

The telephone interviews were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed into text. Assisted by NVivo data analysis software, these transcripts were then coded using a thematic content analysis framework [6, 7]. This method is beneficial given the novelty of ACP in Hong Kong, especially concerning PWAD. The research team met regularly to review the transcriptions and discuss the findings. Identified concepts were categorized into themes, which then reached a consensus. Consistent thematic schemes were applied across all transcripts. The emergence of new themes peaked around the 10th interview and gradually declined with further interviews. Eventually, in the last three interviews, it reached data saturation where no new codes, sub-themes, or themes emerged [11, 12].

2.4 Ethical Approval

The study received approval from the Hospital Authority New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Review (CREC Ref. No. 2023.331) before the recruitment of participants. Participation was voluntary, with digital informed consent obtained immediately before telephone interviews.

3 Results

The average duration of the interviews was 30 min, ranging from 25 to 90 min. The analysis of the interviews revealed five major themes: (1) receptive to ACP, (2) mixed emotions, (3) barriers of ACP, (4) family consensus in decision-making, and (5) benefits of ACP.

3.1 Theme 1—Receptive to ACP

Family caregivers had not heard of ACP before. They were open to ACP when initiated by the healthcare team, particularly if patients had previously expressed a desire to forgo treatments, experienced prior crisis episodes, or had multiple hospital admissions. They believed healthcare professionals (HCPs) knew the best time to initiate such a conversation. In their recollection, there was more emphasis on forgoing CPR or DNACPR. Many accepted ACP due to patient's advanced age and ill health status. They believed that LST was meaningless, which prolonged unnecessary suffering. Some deemed it a waste of resources. Family caregivers who had a similar experience before, or had relatives who died in a palliative care setting, found it easier to discuss ACP. They had a good understanding of patients' health status, and the care demands due to their caregiving journey.

3.2 Theme 2—Mixed Emotions

Considering forgoing LST, most family caregivers were emotionally calm because they accepted death and acknowledged life's limitations. For some caregivers, it was a dilemma between not wanting patients to die or to suffer. After some mental processing, the decision to forgo LST was seen as alleviating patients' suffering, which provided family caregivers with a sense of relief.

Some found it difficult to accept letting go of treatments, which brought sadness. A family caregiver described that she could not accept forgoing LST for her relative initially. She was upset that HCPs were not trying to “save” the patient's life. In the subsequent readmission, the topic was brought up again by another nurse, and she was then able to accept it.

3.3 Theme 3— Barriers to ACP

Lacking awareness of the potential benefits of ACP is a major barrier in Hong Kong for PWD. Before the introduction of ACP by the healthcare team, nearly all family caregivers had not heard of ACP. Some welcomed a more open approach to let the families know about ACP in advance. They thought that the public should know about it. They believed that many families and the public had misunderstandings about LST. The ACP talk was useful for them to learn more about LST. They felt that there was inadequate public education and that only people with personal experience were aware of the possible benefits of ACP for PWD.

Another barrier was that ACP discussions came too late, and patients could not get involved. Many family caregivers believed that it was necessary to involve the patient, the earlier the better. However, they found it difficult to start the conversation due to a lack of skills to discuss with the patient and other family members. They also had many worries, such as upsetting the patient and causing emotional distress. Some caregivers believed the local Chinese culture was not permissive in free discussions of death and dying. Some expressed that they chose avoidance because they could not accept talking about death or believed it was taboo for older people. A family caregiver tried talking to the patient, but the patient refused to discuss his EOL care wishes.

At the beginning of this study, Hong Kong was still under a strict social isolation policy during the COVID era. Family caregivers found discussing ACP inconvenient. They could not tell what was wrong with the patient's health because they were not allowed to visit them at the hospitals or nursing homes. They could not directly communicate with the patient face-to-face. The patients were at the advanced age, 85–100, and their children were also older adults. Such a period created a lot of difficulties and suffering for patients and families.

Another top barrier was that family caregivers were occupied with other challenges, such as preparing patients for hospital discharge, finding nursing homes, running errands, such as obtaining self-paid personal items, and the like. Due to the shortage of hospital beds, patients were required to go home as soon as possible. This was often cited as a competing priority over ACP discussion.

Family caregivers believed that ACP discussion was not that helpful to existing patient care. They expected more follow-up care upon ACP discussion. A family caregiver expressed that providing more physical care to the patient or education on caring for PWAD was a modest anticipation post-ACP discussion.

3.4 Theme 4—Family Consensus in Decision-Making

Family consensus on DNACPR was readily achieved because family members were concerned about patient suffering. Patients were often excluded from discussions for various practical and health reasons. ACP discussion often came too late to involve patient participation. When there were no previous EOL care discussions, the patient's view may not be incorporated in ACP or EOL care. Not all family caregivers could understand the concept of substitute decision-making. They misunderstood the healthcare team seeking their perspective or the family's collective perspective.

Family caregivers assumed that patients were incompetent or unable to participate due to disabilities. They believed discussing with patients would not be fruitful. They also rationalized that patients were illiterate, and thus not knowing what they needed or that they were not willing to listen to others. Some feared that ACP discussions could cause unnecessary worries to patients. This lack of awareness of patient's values or preferences prevailed.

3.5 Theme 5—Benefits of ACP

Family caregivers found themselves more knowledgeable about ACP after the talk and discussion. They believed ACP helped meet patient's holistic needs. ACP discussion could enhance dementia care by considering aspects of care beyond the illness itself. They also found more communication among family members and more attempts to communicate with patients. In pondering ACP, family caregivers had more reflection. Although limited, they wanted more conversation with the patients so their preferences could guide them in future care decisions.

In ACP discussions, family caregivers had more psychological preparation for patients' death. Since families had more discussions, family cohesion helped them psychologically prepare and get support from each other. In the end, it was easier to accept patients' death as well as less regret for unfinished business. A few family members experiencing bereavement mentioned that ACP discussion had helped them to have less guilty feelings because they were there for them.

Many informants reported that they verbally discussed ACP in their family after the ACP talks, even though they did not formally complete ACP in written format. Caregivers also found the ACP process benefiting themselves. The process prompted them to ponder on their own ACP and their older family members'.

4 Discussion

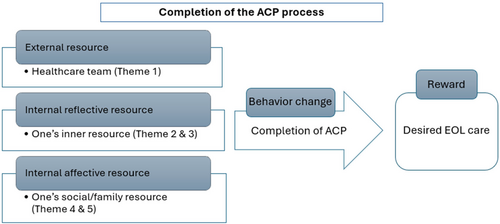

In analyzing the data, there are suggestive patterns of ACP progression. The Behavior Change Resource Model in adopting healthy behavioral change [13] seems to fit well to interpret the results. The model with its original key words in the shaded boxes is presented in Figure 1. The model proposes a focus on resources rather than barriers and shortcomings which empowers the person going through the transformation.

From our data, the healthcare team acted as the external resource to the family caregivers to facilitate the transformation from unaware of ACP or the near EOL situation of the patients to considering ACP, which was shown in Section 3.1. The caregivers experienced various internal struggles and mixed emotions (Section 3.2) with deliberation to relieve suffering as well as overcoming the ACP barriers (Section 3.3) could be considered as accessing their internal reflective resource, adding to the progression of ACP. Building family consensus (Section 3.4) and consequently achieving the benefits of ACP (Section 3.5) could be viewed as mobilizing the internal affective resource or the family/social resource to drive the completion of ACP as a behavior change, reaching their goal of the desired EOL care for their loved ones as rewards. Family caregivers who could not mobilize their internal resources could be seen as stagnant in progressing the ACP process.

4.1 Low Take-Up Rate of ACP

Despite people being receptive to ACP in Hong Kong, it remains a novel concept, requiring time to gain momentum. Besides, individuals could set their priorities and choose whether to engage in ACP [14]. Many dementia patients in Hong Kong prefer family and HCPs to make decisions on their behalf, reflecting a personal choice.

Our findings align with previous studies indicating that ACP is not a priority for patients, caregivers, and HCPs due to ongoing crises and current issues, and they are not future-oriented [15]. Thus, measuring success by the number of completed ACP forms is not warranted. A better strategy may involve having information available and HCPs ACP-trained to facilitate ACP discussions whenever patients and families are ready.

Many local Chinese still treat death as taboo. Family caregivers frequently feel uneasy discussing ACP with patients or older family members, fearing it may cause unnecessary anxiety. As such, they often could not know patients' values or preferences, which undermines the core intent of ACP- to provide goal-concordant care. Therefore, timely and inclusive ACP discussions involving patients and family members are crucial for informed decision-making.

ACP is a gradual process and should be integrated into routine dementia care [14, 16, 17]. Understanding patients' and surrogates' perspectives on current health status and disease trajectory helps provide care that aligns with their preferences. When appropriate, HCPs can invite them to imagine certain circumstances where some medical treatments may bring more suffering than benefits that they would not want. HCPs can naturally introduce ACP by discussing potential medical treatments and their impacts, rather than focusing solely on death or CPR, which can deter patients and families from considering ACP [16], particularly in an abrupt manner.

Appointing a healthcare proxy, which is not part of Hong Kong's Advance Decision on the LST Bill, offers practical benefits by ensuring early discussions and reflecting patients' values and preferences. It can avoid leaving ACP to a late stage when the family must make surrogate decisions, which they may not be comfortable with. Proper documentation of these discussions is essential, rather than relying solely on the AMD form.

Legislation in Hong Kong tends to emphasize signing AMD forms without addressing the ACP process. The issue of form-filling versus documentation needs to be discerned. A comprehensive ACP process with clear documentation is more practical and effective than written documents like AMD forms alone [18], which causes hesitation to many. The AMD's focus on DNACPR overlooks other kinds of life-sustaining treatments. It assumes that basic supportive care includes hydration and nutrition. Since many PWAD cannot swallow without choking, the whole issue of artificial hydration and nutrition (with restraints, etc.) is ignored.

4.2 Cultural Practice in Decision-Making

Achieving family consensus on DNACPR stems from shared concerns about patient suffering. However, excluding patients from these discussions due to dementia is inappropriate. Many family caregivers lack an understanding of substitute decision-making, leading to misconceptions about expressing a collective family perspective.

Maintaining family harmony is a value of high importance in the Chinese context. Consequentially, ACP discussions are unlikely to be pursued proactively when they are perceived as a threat to family harmony. When ACP was prompted by HCPs, family caregivers are often unprepared to make decisions for their ill relatives.

Asians, such as Hong Kong people, are more family-centric, where family involvement in decision-making is a key feature in ACP discussions and EOL care [19]. The cultural expectation of family decisions often creates family conflict, and consensus building may not always be possible, leaving the surrogates feeling lonely without support and adding burdens [20]. Filial expectations, such as in the Chinese culture, could have a negative impact on surrogates experiencing stress and family conflict [21].

Family caregivers often face social pressure to conform with filial expectations and avoid being considered as lacking it. When the decision-makers view filial piety as pursuing all possible LST, forgoing LST will not be an option. Further, filial expectations and family dynamics could contribute to family conflict relating to birth order in EOL decision-making [21]. In Hong Kong, it is a common scenario where elder sons are assumed with higher weighting in family decision-making.

Older Chinese who had strong trust in physicians tended to place less emphasis on EOL discussions with family. And they valued counseling from care providers for EOL discussions with family. Patient education and family engagement in EOL discussions led by trusted healthcare providers may be effective approaches to ensure goal-concordant care [22]. Chinese culture was seen as collectivist, prioritizing family over individual rights, or the individuals must surrender their rights for the betterment or harmony of the whole family. Recent research, however, indicates a shift towards individualism [23-25]. Due to the unique history of Hong Kong, the concept of collectivism may only be one of the facets among contemporary local Chinese. As evident from this study, individual family caregivers hold varying views on ACP, suggesting patient preferences should be solicited early to provide person-centered dementia care. Evidence shows that ACP positively impacts the quality of end-of-life care. ACP is associated with improved outcomes for PWD and their caregivers [26]. Moreover, families could have higher satisfaction with care, and they were more likely to have decided on medical options over time [27]. Increased education and support for families around issues of end-of-life care decisions for PWAD are needed.

4.3 ACP and Quality of Care From Family Caregivers' Perspective

The ACP discussion can raise family caregivers' awareness of the impending final phase of dementia, which is often complicated by their intensified anticipatory grief and high care expectations. Therefore, focusing on current care is essential before advancing ACP discussion. Experts agree that ACP for PWD should cover available care options and their lifelong decision-making principles, as well as allowing time for them to come to terms with their diagnosis and prognosis [14].

A retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of data from nursing homes found no significant differences in family ratings of care between those with and without documentation of LST preferences [28]. This suggests that end-of-life care quality relies more on current care practices than solely on LST documentation or AMD.

A service evaluation revealed that about 80% of residents of care homes chose ACP, with most preferring to remain in the care home [29]. While ACP acceptance increased the likelihood of residents dying in their care homes, it did not reduce hospital admissions. Obstacles to effective ACP implementation include organizational policies, care home staff beliefs about ACP, and manpower shortages. Significant challenges remain to fully realize ACP in actual healthcare settings.

5 Implication for Practice

Healthcare providers play a pivotal role in the patients' ACP process. HCPs must reinforce the ACP process by respecting family caregivers' pace in accepting patients' illness and their emotional readiness to discuss ACP. Since family caregivers find it difficult to initiate these conversations, HCPs should facilitate the ACP process.

Education sessions should address family caregivers' knowledge gap, emotional impacts, death anxiety, and grief reactions. Additionally, these sessions should cover how to engage patients in ACP discussions, particularly when they worry about upsetting patients or view ACP discussions as disrespectful towards elders, and include the concept of substitute decision-making.

Proper training for HCPs is crucial for initiating and facilitating ACP at appropriate moments. Easy-to-use guides or tools can assist laypersons in preparing for these conversations. Enhanced communication skills training for HCPs, including sensitivity to the emotional state of family caregivers and empathetic listening, is vital for building rapport and therapeutic alliance. Empathetic responses [30] can facilitate compassionate communication.

Further EOL education on person-centered dementia care is beneficial in providing support to family caregivers. Ongoing support to address post-ACP care expectations is essential as ACP outcomes include quality of care, satisfaction with care, communication and decision-making [31]. Education addressing caregivers' needs on cognition, emotion, and death-related anxieties are critical.

6 Limitations of the Study

Due to practical reasons and the highly committed caregivers, interviews were not repeated, and transcriptions were not returned to the informants for verification. However, the data were discussed among members of the research team, comprising different healthcare disciplines and a research associate. Due to many unique features of the study, such as a convenient sample from a specific geographic location, inclusion criteria of the informants, the findings may not be generalizable. Cautions should be taken when adapting the findings to another context.

7 Conclusions

Advance care planning is a communication process about future care and treatment preferences, values, and goals with PWD, family, and the healthcare team, preferably with ongoing conversation and documentation. This process continues when PWD becomes unable to make their own decisions [32]. We are obligated to morally provide the best possible care for PWD and caregivers [33], including the final stage of the illness.

In anticipating the progression of dementia, ACP should be approached proactively in advance [34]. It could commence soon following diagnosis when the patients can still actively participate, allowing expression of their needs, values, beliefs, and preferences. However, it could proceed only when patients and families are receptive to the diagnosis and emotionally ready to pursue ACP. ACP discussion should be integrated into the healthcare routine for person-centered dementia care [17].

Quality end-of-life care should be guided by patient's values and preferences, which are important to be aware of early so person-centered dementia care can be achieved. Family caregivers and HCPs are thus pivotal to the quality of life of people living with advanced dementia.

Uniqueness and Contributions of This Study

- −

Despite a cultural taboo, healthcare providers can initiate ACP discussions early to involve PWD to plan for future care.

- −

The actual care practices are more important than ACP discussions alone since ACP aims to achieve goal-concordant care for PWAD. ACP outcomes include quality of care, satisfaction with care, communication and decision-making [31].

- −

The healthcare team can facilitate the ACP process by empowering the family caregivers to access their external and internal resources to achieve ACP outcomes.

- −

Evidence-based culturally sensitive capacity-building training for healthcare providers is crucial for the initiation and facilitation of ACP for PWD.

Author Contributions

Faye Chan: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Kuen Lam: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing – review and editing. Derek Lai: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing – review and editing. Connie Tong: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing – review and editing. Christopher Lum: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing. Jean Woo: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, resources, supervision, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

The study was part of the end-of-life care capacity-building education program supported by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. We express gratitude for the participation of family caregivers in the study. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in this study and took complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Transparency Statement

The lead author, Faye Chan, affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the corresponding author upon request.