Comparison of Cultural Competence Between Dental House Officers and General Dentists: A Cross-Sectional Study

ABSTRACT

Background

All patients deserve quality care, regardless of their cultural, ethnic, or linguistic backgrounds. In Pakistan's diverse society, cultural competence in dentistry is crucial for patient-centered care. This study assesses and compares cultural competence levels between dental house officers (DHOs) and general dentists (GDs).

Methods

A cross-sectional, self-reported study was conducted at Altamash Institute of Dental Medicine, Karachi, over 6 months. A validated questionnaire (α = 0.856) on a 4 to 5-point scale assessed five attributes via Google forms. Data were analyzed using SPSS 23. Independent Sample t-test was used to compare DHOs and GDs, while ANOVA evaluated differences in GDs' qualification and practice settings.

Results

A total of 316 participants (response rate: 79%) were included. The mean age was 24.77 ± 2.02 years for DHOs and 31.32 ± 7.49 years for GDs. Females were predominant, and 27% of GDs worked in private practice. Both groups were somewhat culturally competent, with DHOs showing significantly higher self-perception (2.09 ± 0.61 vs. 1.92 ± 0.26, p = 0.001). However, GDs scored slightly higher in patient-centered communication, practice orientation, and cultural competence behaviors. GDs in private practice were more culturally competent than those working only in OPDs (−0.274*, F: 3.542, p = 0.001).

Conclusion

Overall, participants perceived themselves as somewhat culturally competent. DHOs demonstrated greater self-awareness and sensitivity than GDs. GDs in training and private practice exhibited higher cultural competence than those in OPDs alone.

1 Introduction

Cultural competence has become essential to healthcare, ensuring that all patients receive equitable and effective care regardless of their cultural, ethnicity, or linguistic backgrounds. In dentistry, the importance of cultural competence is increasingly recognized as a critical skill for delivering high-quality and patient-centered care. As societies grow more diverse, dental professionals must be equipped to understand and respect the cultural differences that influence patients' health beliefs, behaviors, and expectations [1, 2].

The concept of cultural competence first gained prominence in the United States during the 1980s, as a response to healthcare disparities affecting minority and marginalized groups [3]. This framework was developed to address the unique needs of these populations by training healthcare providers to deliver care that is sensitive to cultural differences. Another term Intercultural competence is used as a synonym for Cultural Competence in the healthcare field [4]. It is defined as “Knowledge of others; knowledge of self; skills to interpret and relate; skills to discover and/or to interact; valuing others' values, beliefs, and behaviors; and relativizing one's self” is also crucial however, its fundamental role is to maintain culturally competent approaches as we accomplish new knowledge and skills while communicating diverse cultures. So here we are focusing on awareness, which is valuing all cultures and an inclination to make attitudinal changes that support whatever has been learned [5].

In Pakistan, recently a literature review was conducted on cultural competence focusing on nursing with the explanation of its importance that it is “the convergence of cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skills, and cultural sensitivity” [6]. Looking at dental and medical education, cultural competency training is now given its desired importance to nurture such skills to produce skilled and socio-culturally competent professionals [7].

In dentistry, cultural competence is particularly crucial because oral health is closely linked to cultural practices, dietary habits, and communication styles. A culturally competent dentist can better understand and manage these factors, leading to improved patient outcomes and satisfaction [7, 8]. Pakistan is a rich tapestry of cultural and ethnic diversity, where the need for culturally competent dental care is paramount [9]. Dental professionals frequently encounter patients from various backgrounds, each with unique oral health practices and communication patterns. Without proper training in cultural competence, these encounters may lead to misunderstandings, compromised care, and decreased patient satisfaction. Despite the growing recognition of its importance, cultural competence has yet to be fully integrated into dental education in Pakistan [10].

According to a recent report by the Institute of Medicine, patient-physician interactions accounted for one of the contributing factors to healthcare disparities of minorities. This report highlights the need for professionals to be formally trained in navigating such interactions and communicating effectively with multi-ethnic populations. This can be done by providing care while understanding and relating to each patient's beliefs and attitudes with utmost respect [11]. Results from studies conducted in the United States directly relate training of professionals in cultural competence with increase in patient outcomes and satisfaction [12].

Despite the global recognition of the importance of cultural competence, its integration into healthcare education varies across regions. While many countries have made significant strides in incorporating cultural competence into their healthcare curricula, Pakistan has yet to fully embrace this concept within its dental education system. In a country as culturally diverse as Pakistan, the absence of cultural competence training in dental education could lead to misunderstandings, compromised care and reduced patient satisfaction.

This study aims to assess and compare the level of cultural competence among dental house officers and general dentists in Pakistan, with a focus on how cultural competence levels relate to their qualifications and sites of care. The findings will provide crucial insights for dental education programs, emphasizing the need to enhance curricula to include cultural competence training. By doing so, dental professionals can be better prepared to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse patient population, ultimately leading to improved patient interactions and satisfaction. This baseline study also sets the stage for further research into cultural competence among dental professionals, contributing to the ongoing efforts to reduce healthcare disparities.

2 Methods and Materials

A cross-sectional self-reported descriptive study approach was taken up to compare cultural competence between dental house officers and general dentists. Duration of this study was 6 months, conducted at Altamash Institute of Dental Medicine in Karachi. House officers who had frozen their house job or currently not engaged in their house job were excluded along with general dentists who were not actively practicing dentistry. The sample size was calculated using calculator.net. Population was set as 1500 and the calculated sample size by the software was 316 having population proportion 50%, a confidence level of 95% and margin of error within ±5% of the measured value [13].

2.1 Data Collection Instrument

After an extensive literature search of studies evaluating the attributes and constructs required to be culturally competent, a self-administered questionnaire [11] Schwarz's Healthcare Provider Cultural Competence Instrument (HPCCI) [14] was adopted and modified by the authors of this study. The questionnaire after modifications was piloted on 10 general dentists who were not included in this study. The feedback of these individuals regarding the clarity of the questions and any suggestions for improving the questionnaire were noted. The authors reviewed and modified the questionnaire in light of the feedback suggested by those participants after which it was distributed to the same cohort again to check its internal consistency which was up to the satisfactory levels [Cronbach α 0.89].

The first part of the questionnaire covers demographics while the second part is composed of items to be responded on a 5-point scale divided into 4 attributes that are awareness and sensitivity [10 items] with total scores of 50, cultural competence behavior [11 items] with total scores of 55, practice orientation [10 items] with total scores of 50 and patient-centered care [8 items] with the total scores of 45 the scale of all four labeled as Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, Strongly Disagree. The fifth attribute, patient centered communication [4 items] with total scores of 20 assessed on Scale: Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always. The total scores were 220 altogether. However, means scores were taken to report results categorized as first attribute to be Not Aware, Slightly Aware and Aware, second attribute categorized in Negative Behavior, Neutral Behavior, Positive Behavior, then the third attribute focused on Not Practicing, Somewhat practicing, Fully practicing, then comes fourth attribute which was categorized as Not Oriented, Slightly Oriented, Oriented and fifth attribute was Patient cantered care where we categorized as Not towards it, Slightly towards it, Towards it completely and the last one was overall cultural competencel categorized as Not competent, Somewhat Competent, Competent.

2.2 Data Collection Process

The researchers distributed the finalized questionnaire along with consent form through Google forms link via email and social media app WhatsApp. The applicants were also being personally requested (in person or via WhatsApp message and phone call) to fill out the questionnaire with due consideration and without any inhibitions, since no information of the responder was disclosed. A timeline of 2 days had been given to the participants to complete the form. Later on any forms with missing data were excluded from the study.

2.3 Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee [ERC] of Altamash Institute of Dental Medicine, Karachi. [Reference #: AIDM/ERC/10/2023/03]

The participant's identity and their personal details were kept strictly confidential. Only the principal investigator had access to the data. Before participation, informed consent was obtained through a detailed consent form presented at the beginning of the online survey. Participants were provided with comprehensive information about the study's purpose. They were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. The consent form also carried the measures taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity of the participants identity.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

The descriptive variables were analysed using SPSS version 23. Independent Sample t-test was applied to determine if there were any differences among the attributes and over all cultural competence between dental house officers and general dentists. ANOVA was used to determine whether there was any statistically significant difference in the site of care and qualification of general dentists.

3 Results

The questionnaire was distributed to 200 house officers and 200 general dentists. Three hundred and twenty seven participants responded, out of which 11 forms were discarded due to incompleteness and repetitions. The remaining 316 were included in the study [The response rate was 79%] and Cronbach alpha of the questionnaire was 0.856.

Table 1 represents the demographics and professional characteristics of dental house officers and general dentists. It was found that house officers had an average age of around 24.77 years and general dentists were in an average age of 31.32 years with an average of 7 years of experience in their field. The majority participants practicing in clinics located in DHA and Clifton, Bahadurabad following with Gulshan-e-Iqbal and other areas of Karachi. In terms of gender distribution, female professionals were predominant in both groups. When it came to the practice setting, a significant portion of both house officers and general dentists worked in the OPD [Outpatient Department] as house officers are in the beginning of their career and have less opportunity to indulge in general practice. However, a considerable number of general dentists, about 27%, were engaged in private dental practices.

| Variables | House Officers [HO] [N = 157] | General Dentists [GD] [N = 159] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | |||

| 1 | Age | 24.77 ± 2.022 | 31.32 ± 7.488 |

| 2 | Experience | — | 7.00 ± 7.084 |

| Frequency [%] (N = 166) | |||

| 3 | Location of private practice | DHA/Clifton: 42 (25%) | |

| Bahadurabad: 34 (19.8%) | |||

| Gulshan-e-Iqbal: 28 (16.8%) | |||

| Malir Cantt: 25 (15.4%) | |||

| Saddar: 24 (14.5%) | |||

| Other areas: 13 (8%) | |||

| 4 | Gender | House Officers | General dentist |

| Male | 37 [23.5%] | 49 [30.8%] | |

| Female | 120 [76.4%] | 110 [69.2%] | |

| 5 | Site of care | House officers | General dentist |

| Both | 61 [38.8%] | 62 [39%] | |

| Private practice | — | 43 [27%] | |

| OPD | 96 [61.2%] | 54 [34%] | |

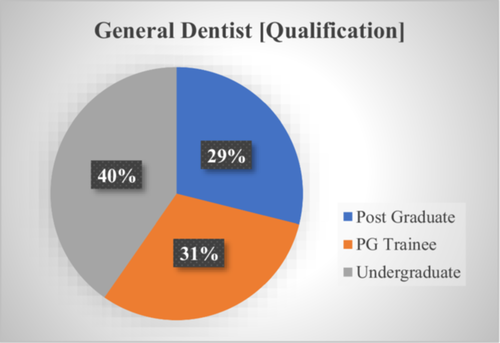

Figure 1 represents General dentists' qualification, displaying that the majority participants were undergraduates, followed by those undergoing post graduate training and then those with postgraduation degrees.

It was found that a majority of the general dentists self-percieved themselves to be aware and sensitive to cultural differences, with 60.8% being fully aware. However, there is room for improvement as they were not sure if they are completely aware of cultural competence. Similarly, professionals also think that they exhibited positive behaviors [64.2%] towards cultural competece. Moreover, third attribute reported in Table 2 seemed to be highly prevalent among the professionals as 81.3% claimed to be fully practicing patient-centered communication, and a significant proportion of the professionals [76.6%] were oriented towards their practice Furthermore, professionals reported to be slightly oriented towards patient-centered care [63.9%]. Overall, professionals precieved themselves somewhat competent with 72.2%, while 19.3% were fully competent. Nonetheless, 8.5% were found to be not competent in cultural competence with statistically significant p value [0.001].

| Attributes [N = 316] | Categorization | Frequency [%] | Mean scores ± SD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Awareness and sensitivity | Not aware | 14 [4.4%] | 2.56 ± 0.579 | < 0.001 |

| Slightly aware | 110 [34.8%] | ||||

| Aware | 192 [60.8%] | ||||

| 2 | Cultural competence behaviors | Negative behavior | 17 [5.4%] | 2.59 ± 0.592 | |

| Neutral behavior | 96[30.4%] | ||||

| Positive behavior | 203 [64.2%] | ||||

| 3 | Patient centered communication | Not practicing | 4 [1.2%] | 2.81 ± 0.424 | |

| Somewhat practicing | 55 [17.4%] | ||||

| Fully practicing | 257 [81.3%] | ||||

| 4 | Practice orientation | Not oriented | 20 [6.3%] | 2.7 ± 0.58 | |

| Slightly oriented | 54 [17.1%] | ||||

| Oriented | 242 [76.6%] | ||||

| 5 | Patient centered Care | Not towards | 28 [8.9%] | 2.18 ± 0.573 | |

| Slightly towards | 202 [63.9%] | ||||

| Towards | 86 [27.2%] | ||||

| 6 | Overall cultural competence | Not competent | 27 [8.5%] | 2.11 ± 0.517 | |

| Somewhat competent | 228 [72.2%] | ||||

| Competent | 61 [19.3%] |

In Table 3 if we look into Awareness and sensitivity and Cultural competence behaviors both groups seem to be aware of cultural competence and have positive behavior towards it with slight higher values for general dentists. Comparing groups for patient centered communication, both reported to be somewhat practicing it and regarding practice orientation, both groups perceived themselves slightly oriented. However, looking at the results for patient centered care, general dentists exhibited lower levels as compared to House officers who proved themselves to be more inclined towards displaying patient centered care. A huge difference in the overall cultural competence was found where surprisingly general dentists did not turn out to be as culturally competent as compared to house officers with statistically significant p value [0.001].

| Attributes | Scores: Mean ± SD | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| House officer | General dentist | |||

| 1 | Awareness and sensitivity | 2.61 ± 0.54 | 2.52 ± 0.61 | < 0.001 |

| 2 | Cultural competence behaviors | 2.55 ± 0.60 | 2.62 ± 0.58 | |

| 3 | Patient centered communication | 2.77 ± 0.35 | 2.85 ± 0.47 | |

| 4 | Practice orientation | 2.65 ± 0.62 | 2.75 ± 0.52 | |

| 5 | Patient centered care | 2.28 ± 0.60 | 2.09 ± 0.52 | |

| 6 | Overall cultural competence | 2.09 ± 0.61 | 1.92 ± 0.26 | |

Table 4 represents significant statistical difference between the relationship between the cultural competence of general dentists and their qualifications. General dentists undergoing training and completed postgraduate education had a significant difference in cultural competence, with those who completed postgraduate education exhibiting lower competence [−0.170] compared to those undergoing training. Also the impact of the site of care on the cultural competence of general dentists revealed that the dentists practicing in private settings had a significantly higher cultural competence [0.274] compared to those working in the OPD. Those working in both settings had a slightly higher cultural competence [0.191] compared to those in the OPD, but this difference was not statistically significant. These results underscore the influence of qualification and practice setting on the cultural competence of general dentists, with postgraduate qualification and private practice showing a positive correlation with higher cultural competence.

| Independent variable | Cultural competence overall scores | Post Hoc test | F [2,154] | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mdff_ | Sig | |||||

| Qualification | Undergraduate [64] | Doing training | 0.063 | 0.429 | 5.148 | 0.007 |

| Post graduate | −0.108 | 0.082 | ||||

| Doing training [46] | Undergraduate | 0.063 | 0.429 | |||

| Post graduate | −0.170* | 0.005 | ||||

| Post graduate [49] | Undergraduate | −0.108 | 0.082 | |||

| Doing training | −0.170* | 0.005 | ||||

| Site of care | [I]Site of care | [J] Site of care | Post Hoc test | F [2,156] | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPD [54] | Both | −0.083 | 0.659 | 3.542 | < 0.001 | |

| Private practice | −0.274* | 0.026 | ||||

| Both [62] | OPD | 0.083 | 0.659 | |||

| Private practice | −0.191 | 0.147 | ||||

| Private practice [43] | OPD | 0.274* | 0.026 | |||

| Both | 0.191 | 0.147 | ||||

- * The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

4 Discussion

The study aimed to assess and compare the levels of cultural competence between dental house officers and general dentists, focusing on their awareness, behaviors, and practice orientations. The findings provide valuable insights into the current state of cultural competence in the dental profession, particularly within a multicultural context like Pakistan. The results indicate that majority of general dentists perceive themselves as being aware and sensitive to cultural differences, with 60.8% reporting full awareness. This suggests that most dental professionals recognize the importance of cultural competence in their practice. However, the fact that nearly 35% of the respondents were only slightly aware, indicates that there is a room for improvement. Awareness is a foundational component of cultural competence [15], and these findings suggest that while the majority of professionals are conscious of cultural differences, there is still a substantial minority who may not fully appreciate the nuances involved. Similar results were found in a recent study by Mohammad Shaikh et al where dentists were lacking an awareness of cultural competene and faced communication barriers in their dental practices [16]. However, previously Marino et al. [17] found contrasting results that most respondents considered themselves fairly competent in various aspects of communication with culturally diverse patients, such as addressing cultural beliefs and involving family members. The difference in findings could be attributed to several factors including variations in assessment tools and contextual differences. Marino et al. may have surveyed a population with more extensive experience or training in cultural competence, whereas the current study includes a broad range of general dentists and house officers at different stages of their careers. Also in our study, house officers reported slightly higher levels of awareness and sensitivity compared to general dentists. This could be attributed to the fact that house officers are more recently exposed to formal education and training, where cultural competence might be emphasized more than in earlier times. However, the statistical significance of this difference [p = 0.001] underscores the need for ongoing training and reinforcement of these concepts throughout a dental professional's career. Similarly, a recent study conducted Pre-Post COVID on 120 dental house officers assessing cultural intelligence in Lahore also endorsed that house officers self-reported to have higher scores on cultural intelligence scale [18]. Contrary to which, a systematic review reported by Khan Y A et al reviewed literature assessing “Effects and issues of integrated cultural competency education in dental school curricula” revealed inconsistent curriculum frameworks and deficiency in faculty preparedness lead to facing challenges in curriculum execution [19] which means it's all about accepting change, faculty training and then development of adequate, relevant curricula, implementation and synchronizing it with teaching of dental education.

Regarding cultural competence behaviors, the study found that 64.2% of professionals reported exhibiting positive behaviors toward cultural competence. This finding aligns with the levels of awareness reported, suggesting that awareness often translates into behavior. Moreover, in this study, the slight difference in cultural competence behaviors between house officers and general dentists, with general dentists scoring slightly higher, suggests that experience and ongoing practice may play a role in shaping these behaviors. However, the overall similarity between the two groups indicates that both groups could benefit from targeted interventions to enhance their cultural competence behaviors. Moreover, the study's findings on patient-centered communication and practice orientation are particularly noteworthy. A vast majority [81.3%] of the professionals reported fully practicing patient-centered communication, which is a critical component of providing culturally competent care. This indicates that most dental professionals recognize the importance of effective communication tailored to individual patient needs and cultural backgrounds. Patient-centered communication and practice orientation were both found to be higher among general dentists. Their extensive experience in handling diverse patient interactions likely contributes to their superior communication skills and holistic approach to patient care. However, patient-centered care was perceived to be lower in general dentists compared to house officers, which might indicate a gap in translating patient-centered communication into actual care practices. This was reflected in the review comprising a systematic literature search on sixteen articles from 2016 to 2024 on cultural competence trainings which lacks support and faces challenges in implementation. It also reported lack of rigorous evaluation, particularly with respect to improvement in patient outcomes [19]. Similarly, a qualitative review with sequential transformative mixed method design discovered significant variations in the undergraduate healthcare curricula. The analysis revealed consistent themes in dentistry curricula were around Ethics and human values for professional practice but less focus was on psychosocial and cultural determinants of health and clinician-patient relationship [1].

Moreover, General dentists undergoing training displayed higher levels of cultural competence compared to those done with postgraduate qualifications. This could be due to the hands-on nature of training programs that emphasize practical application of cultural competence skills, whereas general dentists done with postgraduate qualifications may not focus on continuous improvement in their field. For this purpose, meta-ethnographic synthesis: BEME Guide No. 79, 2023 provided the ACT cultural model as an action-orientated and transformative to enhance cultural competence in health care professionals for professional understanding of oneself and the impact of the professionals' relationships on their surroundings which can improve patient care [20].

General dentists practicing in private set-ups self-reported to be more culturally competent than those working in outpatient departments only. The personalized nature of private practice may foster a deeper understanding and accommodation of individual patient needs, while the structured environment of outpatient departments might limit opportunities for personalized care [21].

Oral health care disparities in Pakistan are widening and mushrooming with the increase in population and limited access to care producing disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities. Looking at the changing world our accreditation bodies have emphasized on expanding curricula on developing students’ cultural competence [22] but measuring current and changing levels of cultural competence is becoming a sustained challenge due to the absence of tested teaching methods, sparse curricular content and lifelong learning approach [23].

5 Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations. First, the study was conducted in a single institution, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other institutions however, the participants were practicing in multiple locations of the city covering major areas. This study may be conducted with multicentre approach covering other institutions. Second, the self-reported nature of the data might introduce bias, as participants may overestimate or underestimate their cultural competence. Moreover, there is a potential recruitment bias as email and WhatsApp was used for distributing the questionnaire and the sample may not fully represent the broader population, particularly those who are less tech-savvy or who prefer other modes of communication. Lastly, the study did not explore the specific educational interventions or experiences that contributed to the reported levels of cultural competence, which could be an area for further research.

6 Recommendations

Steps should be taken to add cultural competence from hidden curriculum to documented curriculum with more real world, hands-on, cultural competency-focused training modules for dental house officers and alumni which is congruent with Harriet Boyd opinion explaining its meaning and importance in dentistry [24]. Promote continuous professional training and cultural competency education for general dentists, especially those pursuing advanced degrees to make them lifelong learners. There is also a need for developing guidelines and procedures that support cultural competency in dental setups, ensuring that all professionals are capable of delivering treatment that is sensitive to cultural differences.

7 Conclusion

This study reveals that all participants perceived themselves somewhat culturally competent. However, in comparison of dental house officers with general dentist it was notified that there a significant disparity in their cultural competency. House officers were more self-aware and sensitive than general dentists overall, while general dentists were slightly more patient-centered and perceived to display culturally competent behaviors. General dentists doing training and those practicing in private set-ups perceived to be more culturally competent as compared to those who had completed the training and those working in the OPD's only. These findings highlight the necessity of focused instruction and continuous professional training to improve cultural competence in dental practice at all levels. By putting these suggestions into practice, healthcare facilities with a diverse patient population may see an improvement in patient satisfaction and treatment outcome.

Author Contributions

Shaur Sarfaraz: investigation, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft, software, conceptualization, validation. Maria Ghani: writing – original draft, data curation, software, resources, methodology. Batool Sajjad: data curation, software, writing – review and editing, resources, methodology. Dinaz Ghandhi: formal analysis, writing – review and editing, visualization. Tayyaba Akram: data curation, writing – review and editing. Maria Shakoor Abbasi: data curation, writing – review and editing, visualization, formal analysis. Naseer Ahmed: writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration, validation, formal analysis, visualization. Artak Heboyan: writing – review and editing, supervision, formal analysis, validation, visualization.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee [ERC] of Altamash Institute of Dental Medicine, Karachi. [Reference #: AIDM/ERC/10/2023/03].

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Transparency Statement

The lead author Shaur Sarfaraz, Artak Heboyan affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. However, the datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.