Lipid profile, ox-LDL, and LCAT activity in patients with endometrial carcinoma and type 2 diabetes: The effect of concurrent disease based on a case–control study

Abstract

Background and Aim

The role of lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) in endometrial cancer (EC) or EC with concurrent type 2 diabetes is still unclear. This study investigated the LCAT activity, ox-LDL, and lipid profile in EC patients with or without type 2 diabetes and compared them with healthy individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes alone.

Methods

In this cross-sectional, case–control study, 93 female participants were recruited. The participants were divided into four groups, including EC with type 2 diabetes (n = 19), EC without type 2 diabetes (n = 17), type 2 diabetes (n = 31), and healthy controls (n = 26). Sociodemographic information, the LCAT activity, triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and ox-LDL levels were collected. One-way analysis of variance and analysis of covariance, Student's t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, and χ2-test were used to compare demographic features and laboratory results among studied groups. Regression analyses were also performed to evaluate the interaction effect between EC and type 2 diabetes on serum LCAT activity.

Results

The LCAT activity was significantly lower, and ox-LDL levels were significantly higher in all patient groups compared to the healthy controls (p < 0.001). EC patients had significantly lower LCAT activity and higher ox-LDL levels than type 2 diabetes and healthy groups (p < 0.05). Higher levels of TG and lower levels of HDL-C were observed in all patient groups compared to the healthy group (all p < 0.001). Patients with EC and concomitant type 2 diabetes had significantly lower serum LDL-C levels than healthy and type 2 diabetes groups (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

The combination of EC and type 2 diabetes had a subadditive effect on LCAT activity and ox-LDL level. The lowest LCAT activity and the highest ox-LDL levels were observed in patients with EC and concurrent type 2 diabetes.

Key points

-

The lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) activity, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) levels, and lipid profile were evaluated among four groups.

-

The groups were endometrial cancer (EC), type 2 diabetes, EC and concurrent type 2 diabetes, and healthy controls.

-

LCAT and high-density lipoprotein decreased, and ox-LDL increased in all three disease groups.

-

The accompaniment of EC and type 2 diabetes significantly increased oxidative stress.

-

The EC group had lower LCAT activity and higher ox-LDL levels than the type 2 diabetes group.

1 INTRODUCTION

Diabetes and its complications are one of the most important burdens on health systems.1 The global prevalence of diabetes was estimated to be 10.5% (536.6 million people) in 2021, increasing to 12.2% (783.2 million people) in 2045.1 Diabetes is associated with increased incidence and mortality of endometrial cancer (EC).2 EC is women's fourth most common cancer.3 There are two different histopathological types of EC. Type I lesions are more common, mainly endometrioid adenocarcinomas, hormone-sensitive, usually at lower stages, with endometrial hyperplasia, hyperestrogenism, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and typically have a better prognosis. Type II lesions are predominantly nonendometrioid serous carcinomas, poorly differentiated, prone to deep invasion and recurrence, and hormone-independent. They arise from atrophic endometrium and have a poor prognosis and higher mortality.2, 4-6

Lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) is an enzyme of the high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) metabolism pathway that converts pre-HDL-C to mature and large spherical HDL-C.7 In the inflammatory state, enzyme activity decreases.8 On the other hand, a decrease in enzyme activity leads to an increase in the inflammatory response.8 Reduced LCAT activity has been reported in patients with diabetes due to elevated oxidative stress.9 The link between LCAT and cancer is still unclear, but decreased LCAT activity has been reported in colorectal, breast, liver, and ovarian cancer.10-15

Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) is an indicator of oxidative stress with atherogenic impact.16 High ox-LDL levels have been reported in diabetes.17 Ox-LDL has an inhibitory effect on HDL-C and LCAT activity.18 HDL-C protects the cardiovascular system and prevents damage by lipid peroxidation products such as ox-LDL.19 In addition, low HDL-C levels are associated with several cancers.20 Recent studies have shown increased ox-LDL levels in breast, ovarian, endometrial, colon, prostate, and pancreatic cancer.21-24

Dyslipidemia patterns, including high triglycerides (TGs), high low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), and low HDL-C levels, are common among patients with type 2 diabetes.25 Dyslipidemia has been shown to be associated with various cancers. Low levels of HDL-C are connected with oral, thyroid, leukemia, Hodgkin's disease, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, nervous system, lung, pancreas, and breast cancer.20, 26 In contrast, some studies have shown that patients with breast cancer have high HDL-C levels.27 Decreased levels of LDL-C are associated with different cancers.27 However, breast, prostate, and renal cancers are among those that may be related to high LDL-C levels.27, 28 Additionally, TG levels could increase in a variety of malignancies like colon cancers.27, 29 Hypercholesterolemia could have an association with an elevated risk of cancers, such as colorectal, prostate, and breast cancers.29, 30

Considering the increased risk of EC in diabetes,31 several underlying mechanisms, such as high-glucose environment, signaling pathway activation, and chronic inflammation, are hypothesized. As a result, metabolic alterations detected in cancer and diabetes could contribute to finding more beneficial treatment options.32 Moreover, the changes in LCAT activity and concomitant lipid profile in EC or EC and concurrent type 2 diabetes, as well as ox-LDL in patients with EC and concurrent type 2 diabetes, have not been fully studied.28 Studying these factors may be beneficial to discover new elements contributing to the pathogenesis of EC and diabetes. The aim of the present study was to investigate the different aspects of biochemical changes in EC and diabetes. In this regard, HDL-associated enzyme, the LCAT activity; ox-LDL as a biomarker of oxidative stress; and lipid profile, including TG, total cholesterol (TC), LDL-C, and HDL-C, were evaluated in patients with EC with and without type 2 diabetes and compared them with healthy individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes alone.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional, case–control study on the basis of consecutive sampling on a group of 93 female participants, divided into four groups, including 19 patients with EC and type 2 diabetes, 17 with EC without type 2 diabetes, 31 with type 2 diabetes alone, and 26 healthy individuals. According to the power of the study as 0.95 and “α” as 0.05, utilizing G*Power software version 3.1.9.2 (Universität Düsseldorf, Germany), a total of 34 was measured for patients with EC.33 Therefore, in the study period, a total of 36 participants with EC were included. In addition, 31 patients with diabetes and 26 healthy controls were enrolled. Patients with early-stage EC, candidates for hysterectomy and those with type two diabetes, irrespective of their ages, were recruited through the gynecologic oncology ward and diabetes clinic of a referral Hospital affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences during 2018–2019, respectively. Healthy controls were selected from healthy volunteers among patients' families without a history of known disease. Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria.34 EC was diagnosed with clinical manifestations and confirmed by the histopathologic study. EC was identified according to the 10th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10: C54). The histology terms described in the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICDO-3) were utilized to categorize subjects with EC into types one and two. This study included all patients with EC during the study period. Exclusion criteria included neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy, history of other chronic diseases, such as liver, kidney, or thyroid dysfunction, other cancers, recurrent EC, history of blood transfusion, and current pregnancy. These exclusion criteria were due to the possible effects of the above-mentioned factors on the oxidative stress markers levels, such as LCAT concentrations. The studied subjects were household women with regular diet and daily activity, in which they were not justified to have excess exercise. None of the patients had a history of smoking or alcohol consumption.

2.2 Data collection and laboratory analysis

Demographic and anthropometric information, including age, weight, height, history of hypertension, duration of type 2 diabetes, menopausal status, menopausal age, socioeconomic data, and education, were recorded through history taking. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the Quetelet formula.35 Socioeconomic status was determined by asking participants about their belonging materials, including vehicle, home, and household appliance ownership, and categorized into low, middle, and high classes. Postmenopausal status was confirmed following a 12-month menstruation absence, which was obtained through history taking. Blood pressure was measured using a digital sphygmomanometer after asking patients to sit and hold their right hand at heart level with their palms facing upward and assumed an average calculated based on three readings. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) higher than 140 and 90 mmHg were defined as hypertension, respectively. A total of 10 mL venous blood samples were obtained in the morning after the participants fasted for at least 12 h. The samples were collected into ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid-containing (1.5 mg/mL) tubes. Plasma was isolated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG levels were measured by routine enzymatic methods (Technicon RA-analyzer; Pars Azmoon). Ox-LDL was measured using a commercially available sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method (Mercodia) with intra-assay coefficient of variants (CV)%: 4; interassay CV%: 7.3 (U/L); detection limit: 0.6 (mU/L); ranged from 1.4–22.5 (mU/L). Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level was estimated by high-performance liquid chromatography. Glucose level was assessed by the glucose oxidase method (intra-assay CV = 2.1%; interassay CV = 2.6%).

Plasma LCAT activity level was assayed by fluorescence spectrophotometry, similar to the Nakhjavani et al.36 study. A commercially available kit (Roar Biomedical Inc.) was used. Plasma was incubated with a fluorescent substrate. A Hitachi F-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer measured the fluorescence intensity of the intact substrate at 470 nm. As LCAT hydrolyzed the substrate, a monomer detectable at 390 nm was producing. LCAT activity was estimated by measuring the change in 470/390 nm emission intensity (intra-assay and interassay CV were <5%). This study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The medical ethics council of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (IR.TUMS.IKHC.REC.1397.340). All participants were provided with the details of the study protocol and required information as well as all potential risks or benefits, such as a consultant for any impaired factors in their blood tests. Consequently, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.3 Statistical analysis

The values of mean ± standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated. The normality test was done using the Shapiro–Wilk test. One-way analysis of variance and post-hoc test as well as analysis of covariance were used to compare groups based on age, BMI, SBP, DBP, TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, ox-LDL, and LCAT activity level. Student's t-test was used to compare EC with or without type 2 diabetes and the diabetic group based on fasting blood sugar (FBS) and HbA1c. Due to the nonnormal distribution of type 2 diabetes duration, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test was utilized to compare the durations of type 2 diabetes between groups. χ2-test was performed to compare the menopausal status among the groups. The association between LCAT level and other variables in each group was also studied using a Pearson correlation coefficient. Linear regression analyses were performed to assess the effects of diabetes, EC, and concurrent status on LCAT activity in STATA. Due to the number of patients, we tried to have no missing values in all studied variables. Two-sided tests with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS software version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and Stata software version 14.0 (StataCorp LLC).

3 RESULTS

In this cross-sectional, case–control survey, 93 female participants were studied. There were no significant differences between the groups concerning SBP, DBP, TC, and menopausal age (p values were 0.676, 0.892, 0.563, and 0.321, respectively). Age, BMI, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, ox-LDL, and LCAT activity levels were significantly different between the groups (all p < 0.05) (Table 1). The median duration of type 2 diabetes (IQR) was significantly different between diabetic patients with EC (2 ± 2 years) and without EC (4 ± 3 years) (Mann–Whitney U = 106.50; p = 0.001). The age of diabetic patients with EC (58.37 ± 8.77) was significantly higher than the other groups (p < 0.05). No significant difference was observed between the other three groups. As recommended by ADA guideline to maintain LDL levels of less than 70 mg/dL in patients with diabetes, approximately 95% of study participants with diabetes were prescribed statins. The studied population was mostly homogeneous, with middle to high school education degree, and belonged to the middle class. Participants mainly had healthcare access and insurance coverage. Demographic and clinical variables in the case and control groups are presented in Table 1.

| Variable | Patients with endometrial carcinoma | Patients with type 2 diabetes without endometrial carcinoma (n = 31) | Healthy controls (n = 26) | F (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With type 2 diabetes (n = 19) | Without type 2 diabetes (n = 17) | ||||

| Age (years) | 58.37 ± 8.77#, $ | 51.47 ± 9.30 | 49.68 ± 6.46 | 49.62 ± 6.28 | 6.43 (0.001) |

| Menopausal age (years) | 48.94 ± 3.54 | 46.07 ± 7.16 | 46.00 ± 6.00 | 47.46 ± 5.51 | 1.18 (0.321) |

| Postmenopause (%) | 89.5% | 47.1% | 48.4% | 42.3% | 11.78 (0.008) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.41 ± 6.39 | 31.83 ± 5.78# | 28.14 ± 4.27 | 27.32 ± 3.33 | 3.63 (0.016) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 125.19 ± 13.04 | 120.73 ± 13.59 | 124.35 ± 11.37 | 124.42 ± 10.42 | 0.49 (0.68) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.63 ± 10.33 | 78.20 ± 8.05 | 78.84 ± 9.69 | 77.88 ± 8.62 | 0.20 (0.89) |

| Duration of type 2 diabetes (years)a | 2.58 ± 2.34 | - | 5.23 ± 3.56 | - | 106.50b (0.001) |

| FBS (mg/dL)c | 138.53 ± 41.22 | 121.00 ± 27.45 | 196.81 ± 67.23 | 88.50 ± 6.16 | 3.80d (<0.001) |

| HbA1C (%) | 7.24 ± 1.12 | 5.46 ± 0.74 | 9.77 ± 2.25 | 4.96 ± 0.29 | 4.31 (<0.001) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 191.89 ± 49.71 | 209.70 ± 54.63 | 208.16 ± 47.31 | 207.11 ± 25.16 | 0.68 (0.56) |

| TG (mg/dl) | 204.21 ± 85.35 | 191.06 ± 61.77# | 175.87 ± 69.87# | 107.31 ± 36.27 | 10.45 (<0.001) |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 34.05 ± 8.34, | 35.82 ± 8.01#, $ | 44.70 ± 9.39# | 54.69 ± 11.27 | 21.94 (<0.001) |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 77.63 ± 28.12, | 89.17 ± 31.33 | 111.20 ± 36.36 | 110.19 ± 12.64 | 7.289 (<0.001) |

| ox-LDL (mU/L) | 17.47 ± 0.84#-α | 12.36 ± 0.91#, $ | 13.80 ± 1.35# | 7.57 ± 1.36 | 218.69 (<0.001) |

| ox-LDL/LDL-C | 0.24 ± 0.06#-α | 0.15 ± 0.06# | 0.14 ± 0.07# | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 30.73 (<0.001) |

| ox-LDL/HDL-C | 0.54 ± 0.14#-α | 0.36 ± 0.08# | 0.32 ± 0.07# | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 77.53 (<0.001) |

| LCAT activity (nmol/mL/h) | 28.31 ± 2.78#, $ | 34.00 ± 4.97#, $ | 46.58 ± 9.47# | 59.92 ± 2.46 | 236.73 (<0.001) |

| Medications, % (n) | |||||

| Oral agents | 78.9% (15) | - | 80.6% (25) | - | 0.817 |

| Insulin + metformin | 15.7% (3) | - | 12.9% (4) | - | |

| Insulin | 5.2% (1) | - | 6.4% (2) | - | |

| Statin | 94.7% (18) | - | 93.5% (29) | - | 0.594 |

- Note: Data are presented as mean ± SD.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LCAT, lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TG, triglyceride.

- # p < 0.05 versus healthy group.

- $ p < 0.05 versus type 2 diabetes.

- α p < 0.05 versus EC without type 2 diabetes.

- a Based on Mann–Whitney U-test.

- b Statistic value: Mann–Whitney U-test.

- c Based on Student's t-test.

- d Statistic value: t.

Comparing menopausal status among groups showed different frequencies of premenopausal and postmenopausal states. Postmenopausal status was higher in patients with EC and type 2 diabetes (χ2 = 11.78, p = 0.008).

The BMI in the EC patients without type 2 diabetes (31.83 ± 5.78) was significantly higher than the healthy group (27.32 ± 3.33) (p ≤ 0.05). However, no significant difference was observed between the other groups.

The FBS and HbA1c values in the diabetic group were significantly higher than those with EC and concurrent type 2 diabetes (t = 3.80 and p < 0.001, t = 4.31 and p < 0.001, respectively).

Patients in the type 2 diabetes and healthy groups had significantly higher plasma LDL-C levels than patients with EC and type 2 diabetes (p ≤ 0.05). There was no significant difference between the EC patients without type 2 diabetes compared to type 2 diabetes and healthy groups. The ox-LDL levels in patients with EC and concomitant type 2 diabetes (17.47 ± 0.84) were significantly higher than the other three groups (all p ≤ 0.05). The EC patients with (17.47 ± 0.84) and without type 2 diabetes (12.36 ± 0.91) had significantly higher ox-LDL levels than the healthy group (p ≤ 0.05). In the diabetic group, ox-LDL (13.80 ± 1.35) was significantly higher than in the healthy individuals (p ≤ 0.05). The plasma HDL-C levels in healthy controls (54.69 ± 11.27) and patients with type 2 diabetes (44.70 ± 9.39) were significantly higher than in EC patients with (34.05 ± 8.34) and without type 2 diabetes (35.82 ± 8.01) (p ≤ 0.05). However, there was no significant difference between EC groups concerning HDL-C levels. Compared to the healthy controls, plasma TG levels were significantly higher in both EC groups (p ≤ 0.05). The ox-LDL/LDL-C ratio was significantly higher in EC patients with type 2 diabetes than in other groups (all p ≤ 0.05). The ox-LDL/LDL-C ratio was significantly higher in the type 2 diabetes group and EC patients without type 2 diabetes compared to the healthy one. However, no significant difference was observed between the type 2 diabetes group and EC patients without type 2 diabetes. The ox-LDL/HDL-C ratio in all three patient groups was significantly higher than in the healthy group (all p ≤ 0.05). Also, the ox-LDL/HDL-C ratio was significantly higher in EC patients with type 2 diabetes compared to other groups.

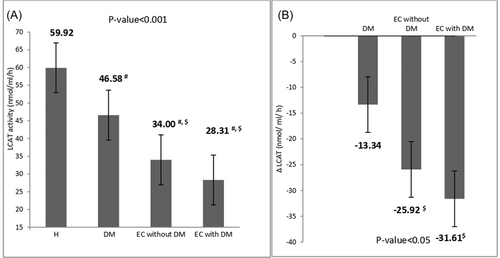

The highest LCAT activity was observed in the healthy controls, while the lowest activity was seen in EC patients with type 2 diabetes. According to pairwise comparisons, LCAT activity was significantly lower in EC patients with and without type 2 diabetes compared to the type 2 diabetes patients and the healthy group (p < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference between the two EC groups regarding LCAT levels (28.31 ± 2.78 vs. 34.00 ± 4.97, p = 0.77). Patients with type 2 diabetes had significantly lower LCAT activity levels than the control group (46.58 ± 9.47 vs. 59.92 ± 2.46, p < 0.001).

After adjusting for BMI, age, LDL-C, ox-LDL, HDL-C, and TG, the LCAT activity was compared between the groups, which yielded a significant difference (F = 42.43, p < 0.001) (Figure 1A). Additionally, after adjusting for FBS, HbA1c, and duration of diabetes, LCAT activity in EC patients with type 2 diabetes was compared with the type 2 diabetes group. The LCAT activity was significantly higher in the type 2 diabetes group (F = 136.41, p < 0.001).

According to the histopathological type of EC, the patients with EC were divided into two groups: 25 patients with type I EC (endometrioid) and 12 with type II EC (nonendometrioid). After controlling for age, BMI, FBS, HbA1C, cholesterol, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, and ox-LDL, no significant difference was observed between these two groups (all p > 0.05).

This study classified each histopathological type group according to the presence of type 2 diabetes (number of patients and mean ± SD of LCAT activity in each group was presented): endometrioid EC with type 2 diabetes (N = 13, 27.84 ± 2.11), endometrioid EC without type 2 diabetes (N = 12, 35.36 ± 5.25), nonendometrioid EC with type 2 diabetes (N = 6, 29.33 ± 3.93), and nonendometrioid EC without type 2 diabetes (N = 6, 31.16 ± 3.67). Tukey's test showed that the LCAT level in endometrioid EC patients without type 2 diabetes was significantly higher than in endometrioid EC patients with type 2 diabetes (p = 0.001). However, there were no similar findings in nonendometrioid EC patients (p = 0.854) (Table 2.).

| Studied groups | Endometrioid EC | Nonendometrioid EC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

With type 2 diabetes (N = 13) |

Without type 2 diabetes (N = 12) |

With type 2 diabetes (N = 6) |

Without type 2 diabetes (N = 6) |

|

| LCAT activity | 27.84 ± 2.11* | 35.36 ± 5.25 | 29.33 ± 3.93 | 31.16 ± 3.67 |

- Abbreviations: EC, endometrial cancer; LCAT, lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase.

- * p < 0.05 versus endometrioid EC without type 2 diabetes.

The current study also analyzed the interaction between EC and type 2 diabetes on serum LCAT activity. Regression analysis (β ± SE) obtained three effects: type 2 diabetes alone, EC alone, and the combined effect of type 2 diabetes and EC on measured marker levels. The main effect of type 2 diabetes was −13.34 ± 1.6 (p = 0.001), and the main effect of EC was −25.92 ± 1.9 (p = 0.001). A significant interaction effect between EC and type 2 diabetes was observed on LCAT activity (−31.61 ± 2.63, p = 0.005). The company effect of both diseases was less than the simple quantitative addition of the impact of each one, implying that the association between EC and type 2 diabetes represents a sub-additive interaction effect on LCAT activity (Figure 1B).

The correlation between LCAT levels and other variables in each group was also studied. In patients with EC and type 2 diabetes, LCAT activity was not related to any other variable. In the EC patients without type 2 diabetes, LCAT activity was positively correlated with BMI (r = 0.612, p = 0.015). In the type 2 diabetes group, LCAT activity was negatively correlated with HbA1c (r = −0.686, p < 0.001) and ox-LDL/LDL-C ratio (r = −0.508, p = 0.004). A weak positive correlation was observed between LCAT activity and TC in the type 2 diabetes group (r = 0.369, p = 0.041). In the healthy group, LCAT activity had a negative correlation with SBP (r = −0.549, p = 0.004), DBP (r = −0.559, p = 0.003), TG (r = −0.448, p = 0.022), and TC (r = −0.454, p = 0.020) (Table 3).

| Studied groups | Correlation between LCAT activity and | Correlation coefficient | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial carcinoma without type 2 diabetes | BMI | 0.612 | 0.015 | |

| Type 2 diabetes | HbA1c | −0.686 | <0.001 | |

| ox-LDL/LDL-C ratio | −0.508 | 0.004 | ||

| Total cholesterol | 0.369 | 0.041 | ||

| Healthy controls | Blood pressure | SBP | −0.549 | 0.004 |

| DBP | −0.559 | 0.003 | ||

| TG | −0.448 | 0.022 | ||

| Total cholesterol | −0.454 | 0.020 | ||

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; LCAT, lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TG, triglyceride.

4 DISCUSSION

In this study, the LCAT activity was significantly lower, and ox-LDL levels were significantly higher in all patient groups compared to the healthy control group. EC patients had significantly lower LCAT activity and higher ox-LDL levels than type 2 diabetes and healthy groups. This study observed significantly higher TG and lower HDL-C in all patient groups compared to the healthy controls. Patients with EC and concomitant type 2 diabetes had significantly lower serum LDL-C levels than healthy and type 2 diabetes groups. The TC level had no significant difference between the groups.

The LCAT activity was lower in EC patients compared to healthy controls. There are limited studies on LCAT activity and cancer. Mihajlovic et al.10 showed decreased LCAT activity in colorectal cancer patients compared to the healthy control group. Decreased LCAT activity has been also reported in breast and ovarian cancer.11, 37 Cancer can induce oxidative stress, reducing LCAT activity.8 In line with earlier findings, the current analysis observed the lowest LCAT activity in EC patients with concomitant type 2 diabetes. However, the accompaniment of EC and type 2 diabetes had a subadditive effect on LCAT activity. In this regard, earlier studies have reported decreased LCAT activity in type 2 diabetes,9, 38, 39 particularly in women.9 The current study observed the lowest level of LCAT activity and the highest level of ox-LDL in patients with EC and concomitant type 2 diabetes. On the contrary, the highest levels of LCAT activity and the lowest ox-LDL levels were seen in the healthy group. Previous studies reported that higher levels of ox-LDL decrease LCAT activity, inhibit the enzyme, and worsen this chaotic metabolic state as a vicious cycle. As a result, the LCAT activity could be negatively correlated with ox-LDL levels.18

The levels of ox-LDL, ox-LDL/LDL-C, and ox-LDL/HDL-C were significantly higher in all patient groups compared to healthy controls in the current study. The ox-LDL level in the EC group was significantly higher than type 2 diabetes and healthy groups. Elevated serum ox-LDL levels have been reported in breast, ovarian, endometrial, colon, prostate, and pancreatic cancer.21-24 Recent studies have shown that ox-LDL has a predisposing role in cancer development, progression, and prognosis.40 An in vitro study on ovarian carcinoma cells showed that ox-LDL stimulates cell proliferation and, as a hypothesis, increased ox-LDL levels may worsen ovarian cancer outcomes.41 The impact of ox-LDL on the cell cycle is not yet clearly explained, but elevated levels of ox-LDL induce the proliferation of various cell types.42 An in vitro study on human neonatal fibroblasts showed that ox-LDL stimulated a significant increase in cell cycle-activating proteins associated with cell cycle progression.43 Cancer can outbreak and progress when physiological cell cycle checkpoints that control cell function, growth, mitosis, and apoptosis are damaged or lost.44 Therefore, in a disturbed metabolic state, cancer will emanate and progress.45 Hypothetically, the higher oxidative stress leads to structural or functional damage of cell regulatory proteins.46 Oxidative stress can activate transcription factors, inflammatory pathways, and biomolecules involved in cell cycle regulation and DNA damage control and leads to the deterioration of diabetes by producing reactive oxygen species. Other free radicals and oxidants also disrupt glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism.47 As previously shown, the concomitant status of diabetes and endometrial cancer resulted in higher levels of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine as an oxidative marker of damaged DNA compared to cancer alone.48 Heat-shock protein 70 is also an indicator of stress condition, raising in patients with EC and type 2 diabetes compared to those without diabetes.49 Therefore, according to the results of the current investigation, in which the highest levels of ox-LDL and the lowest levels of LCAT activity were detected in the presence of concurrent type 2 diabetes and EC, controlling each disease alone could result in better outcomes.

As mentioned earlier, the patients with EC had significantly lower LCAT activity than other groups in the current investigation. According to the literature, decreased LCAT activity could be accompanied by HDL-C levels reduction.10 Low HDL-C levels are associated with different cancers.50, 51 In a cohort study, low HDL-C levels were associated with a higher incidence of lung cancer.51 Additionally, an association between lower HDL-C levels and higher breast cancer incidence in premenopausal women has been reported.50 Similar to previous studies, this study showed significantly lower serum HDL-C levels in all patient groups compared to the healthy controls. No significant difference was detected between the two groups of patients with EC. However, the serum HDL-C level was significantly lower in patients with EC than in the type 2 diabetes group. The underlying cause could be the relationship between LCAT activity and HDL-C level.

Activation of cholesterol metabolism pathways is strongly associated with cell growth.52 Elevated demand for cholesterol and LDL-C for rapid cell growth in cancerous cells may decrease serum LDL-C levels.53 Low LDL-C is strongly associated with an increased risk of cancer.54 In addition, low concentrations of LDL-C could be driven by the malnutritional aspects of cancer.55 A study showed that patients with diabetes and low LDL-C were at an increased risk of developing cancer.56 This is in line with our findings. Patients with EC and concomitant type 2 diabetes had significantly lower serum LDL-C levels than healthy and type 2 diabetes groups in the present study. EC has been also shown to be associated with higher TG levels.57 Consistently, the current analysis revealed that the TG levels in all three patient groups were significantly higher than healthy controls.

There were several limitations in this investigation. First, a relatively small number of patients were enrolled during the study period (from 2018 to 2019). Second, considering the cross-sectional nature of the study, a causal relationship between LCAT activity or ox-LDL levels and EC cannot be concluded. Therefore, the potential clinical implications of these findings cannot be fully evaluated. Besides, determining whether the link between LCAT activity, lipid profile, and the studied diseases, including diabetes and EC, is an actual association is not feasible. Third, there may be unknown confounding factors that were not included in our analyses. More studies with larger sample sizes are needed to determine the exact relationship between the variables in this study.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The lowest LCAT activity and the highest ox-LDL levels were observed in patients with EC and concurrent type 2 diabetes. The status of concomitant major systemic illness, such as type 2 diabetes and EC, could lead to more severe consequences than either disease alone. As a result, focusing on managing each disease separately can significantly improve metabolic disturbances. Further research, especially cohort studies, is needed to confirm or refute this association.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Reihane Qahremani: Conceptualization; formal analysis; writing—original draft. Soghra Rabizadeh: Methodology; writing—original draft. Hossein Mirmiranpoor: Formal analysis; investigation. Amirhossein Yadegar: Methodology; Writing—review & editing; Formal analysis. Fatemeh Mohammadi: Methodology; writing—original draft; Formal analysis. Leyla Sahebi: Investigation. Firouzeh Heidari: Formal analysis. Alireza Esteghamati: Conceptualization; supervision; writing—review and editing. Manouchehr Nakhjavani: Conceptualization; project administration; supervision; writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the patients for their participation and kind cooperation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The medical ethics council of Tehran University of medical sciences approved the study protocol (IR.TUMS.IKHC.REC.1397.340), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author Manouchehr Nakhjavani had full access to all of the data in this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The participants have consented to the submission of the study to the journal.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

The lead author Manouchehr Nakhjavani affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.