Drivers of diversity on boards: The impact of the Sarbanes-Oxley act

Abstract

This study investigates how firm structure, chief executive officer (CEO) power, and federal legislation influence hiring of corporate directors from a diverse background. Combining the value-in-diversity hypothesis and the similarity-attraction paradigm, we examine the impact of economically rational (i.e., business need) and social preference (i.e., similar-to-me bias) drivers of board diversity post-the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). Using a sample of S&P 1500 firms from an eight-year period spanning SOX, we find that SOX is positively correlated with board diversity. Although SOX was not intended to increase board diversity, the changes it put in place have subsequently facilitated more board diversity. Results show that the economically rational predictor (firm operational complexity) had a positive and statistically significant effect on board diversity pre-SOX but that effect disappeared post-SOX. Meanwhile, CEO power, a social preference inhibitor of board diversity, had a negative and statistically significant relationship with board diversity pre-SOX which also disappeared post-SOX. It appears that SOX has mitigated both economically rational drivers to want more diversity as well as social preference drivers to want less diversity. Implications of these findings for research and practice are discussed.

One of the most important personnel decisions that will ever be made for a firm is determining who will govern the firm. The board of directors is a governance body which is tasked with advising the firm's chief executive officer (CEO) and top executives, monitoring them, and providing resources to those executives by using their social networks (Johnson, Daily, & Ellstrand, 1996). The board of directors has been shown to influence corporate strategic decision-making, which is why board members are considered part of the upper echelons and critical team members in a firm's human capital (Deutsch, 2005). A recent study of board diversity found that diversity at the top may help break the glass ceiling, as board gender diversity had a trickle-down effect, meaning that it was associated with more gender diversity at the executive level (Gould, Kulik, & Sardeshmukh, 2018). An important question that needs to be answered then is what factors can help enhance board diversity.

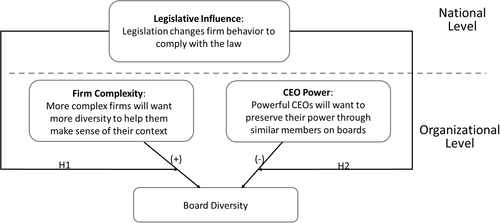

In the study of antecedents to board diversity, it is important to consider the national factors and organizational factors that drive board diversity. For example, within a firm the chief executive officer (CEO) is a very powerful individual and research shows that CEOs can both influence board membership (Westphal & Zajac, 1995, 1997) and react to changes in board structures, such as independence from management, by adjusting their behavior toward the board in a way that helps them maintain their influence (Westphal, 1998). The structure of the organization itself has also been shown to influence board diversity, with research showing that organizational size, industry type, and firm diversification strategy all influence women's representation on boards (Hillman, Shropshire, & Cannella, 2007). Moreover, national institutional systems (especially cultural and legal systems) have also been shown to predict female board representation (Grosvold & Brammer, 2011). In this investigation, we examine how firm structure in the form of firm operational complexity, CEO power, and federal legislation (i.e., the 2002 passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act; SOX) influence diversity considerations in the recruitment of directors. Firm operational complexity is proposed to be a predictor of more board diversity because the board needs more knowledge in an environment that is complex. CEO power is proposed to be a predictor of less board diversity because CEOs have been shown to benefit from similar-to-me biases when boards are demographically similar to them (Westphal & Zajac, 1995, 1997). Finally, we focus on SOX because that was the most significant legislative reform to the governance of public corporations within the past few decades. We propose that these national level (passing SOX) and organizational level (firm operational complexity and CEO power) factors jointly influence board diversity. See Figure 1 for an illustration of our conceptual model.

The Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act of 2002 and subsequent changes in stock listing rules are perhaps the most significant reforms to the governance of public corporations in the United States since the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission in the 1930s, and they have had widespread impacts on the composition of boards (Valenti, 2008; Wintoki, 2007). Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether these reforms only added outside directors as tokens or whether they influenced board composition in a meaningful way (Linck, Netter, & Yang, 2008; Withers, Hillman, & Cannella Jr., 2012). Without understanding how significant governance regulation changes affect the make-up of boards in terms of director attributes, our theoretical knowledge of these relationships is limited and our ability to make practical recommendations is compromised. This presents an issue considering the scrutiny of board activity (Dalton, Hitt, Certo, & Dalton, 2007). Thus, clarifying the outcomes of SOX and subsequent changes in listing rules on firms (e.g., board diversity) is important for both corporate governance theory and practice alike.

Although SOX-related board independence requirements did not ask listed companies to increase board diversity per se, this requirement did force companies to look beyond the traditional pool of corporate executives for new, independent directors. Thus, it is possible that SOX indirectly encouraged companies to hire directors with more diverse backgrounds. The present study investigates whether the passage of SOX and related exchange listing rules affected board diversity considering two important moderators: the operational complexity of the firm (an economically rational predictor for board diversity) and the power of the CEO (a social preference predictor against board diversity).

Building upon Withers et al.'s (2012) framework dividing drivers of the board's make-up into economically rational and socially embedded perspectives, we examine how SOX and the accompanying requirements affect the relationships that both economically rational and social preference drivers have on boards' gender and ethnic diversity, which, for simplicity, we refer to as “diversity.” We analyze these relationships using a sample of S&P 1500 firms over an eight-year period encompassing the adoption of SOX. We find that the passage of SOX is positively associated with board diversity. SOX and subsequent listing rule changes reduced the effect of CEO power, a socially embedded inhibitor of board diversity pre-SOX, as well as operational complexity, an economically rational predictor of board diversity pre-SOX.

The findings of our study contribute to corporate governance theory and practice in several ways. With respect to our theoretical understanding of board diversity, the finding that SOX weakened the effect of both positive and negative drivers of board diversity enhances our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the make-up of boards. Specifically, our results suggest that similarity-attraction effects (Byrne, 1971) are mitigated because the effect of CEO power on board diversity was negative pre-SOX, but this negative effect disappears post-SOX. Furthermore, the finding that operational complexity, an economically rational determinant of board diversity, was also reduced suggests that boards attempt to respond quickly to regulatory changes. These results imply that legislation can mitigate both social processes driving the composition of boards (i.e., personal preferences and biases) as well as rational processes (i.e., business need). The findings suggest that environmental shocks such as SOX can mitigate, directly or indirectly, the effects of social biases that affect governance practices (O'Higgins, 2002; Zelechowski & Bilimoria, 2004).

Beyond addressing calls for more research to understand not only the antecedents of board diversity (e.g., Johnson, Schnatterly, & Hill, 2013) but also whether significant governmental regulation affects these drivers (e.g., Linck et al., 2008; Withers et al., 2012), our findings contribute to the practice of corporate governance as well. In particular, scholars have come under scrutiny for the inability to make normative recommendations regarding how to improve the practice of corporate governance (Daily, Dalton, & Cannella, 2003; Dowell, Shackell, & Stuart, 2011). The findings of this study suggest that corporations and legislative bodies can take steps to mitigate certain detrimental actions that might be driven by social preferences associated with individuals' biases and preferences. However, the effect of firm operational complexity on board diversity was also reduced, as firms generally became more diverse post-SOX. These results indicate that legislation aimed at altering the composition of boards can be a double-edged sword, because with respect to rational reasons to promote diversity, such as operational complexity, market mechanisms may be preferable. However, the results also suggest that governance reforms aimed at removing personal biases that affect board diversity are effective particularly in settings where CEOs are powerful, because it requires them to make changes that indirectly enhance board diversity.

1 THEORY DEVELOPMENT AND HYPOTHESES

A few studies have examined antecedents to diversity on boards and determined that organizational as well as national factors predict board diversity. For example, the presence of women and foreign directors on nominating committees is positively associated with more women and foreign directors on boards (Kaczmarek, Kimino, & Pye, 2012). Hillman et al. (2007) found that larger organizations, organizations in industries with more women, and organizations having board networks with links to other boards with women directors all increased the representation of women on boards. Moreover, Grosvold and Brammer (2011) found that national institutional systems are strong predictors of women on boards. Specifically, “half of the variation in the presence of women on corporate boards across countries is attributable to national institutional systems and that culturally and legally-oriented institutional systems appear to play the most significant role in shaping board diversity” (Grosvold & Brammer, 2011, p. 116). Recognizing the importance of national regulations in predicting board diversity, the present study examines the impact of the 2002 passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) on diversity in boards of directors in the US. Although diversity was not the intended goal of SOX, we explain how SOX impacted board diversity and changed the nature of the relationship between firm operational complexity and board diversity as well as the relationship between CEO power and board diversity.

1.1 Sarbanes-Oxley and its effect on boards

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002 and subsequent exchange listing standards regulated both the membership and certain functions of boards of directors. Every publicly traded company is now required to have a majority of board members be independent (i.e., outside members who are not employed by the firm). Moreover, the three most powerful committees on the board (audit, compensation, and governance) must be entirely comprised of independent directors. As a result of SOX, many companies have added outside board members (Zhang, Zhu, & Ding, 2013). Dalton and Dalton (2010, p. 262) have pointed out that SOX created a setting that is “conducive to the continued advancement of women to corporate boards” because bringing in directors from outside the organization who are not firm executives increases the odds that more women will join boards. Therefore, although SOX did not specifically intend to regulate demographic diversity on boards, an increase in board diversity is one byproduct of this legislation, and we anticipate finding a positive SOX-board diversity correlation. Next, we turn our attention to economically rational and socially embedded predictors of board diversity.

1.2 Economically rational and socially embedded drivers of Board Diversity

As a review of boards of directors research by Withers et al. (2012) highlights, scholars typically take one of two perspectives when investigating what drives the make-up of boards: economically rational and socially embedded. The economically rational perspective suggests that the diversity of the board is driven by whether or not diversity is expected to benefit or cost the organization. Since directors of different genders and ethnicities have different knowledge and perspectives, the economically rational perspective argues that boards will become more heterogeneous when diverse views are expected to benefit the organization. For example, Arfken, Bellar, and Helms (2004, p. 177) note that diverse directors are a “critical but overlooked resource” who can help organizations ensure that they are meeting the needs of diverse constituents. Meanwhile, Staples (2008) finds that in the wake of globalization, corporations are increasingly adopting multinational boards to glean their localized knowledge. These studies point to board diversity as an attempt to adopt a board that is beneficial given the context in which the organization operates.

1.2.1 Firm operational complexity: An economically rational driver of board diversity

Scholars argue that organizations with more complex operations are associated with more diverse boards for two economically rational reasons. First, as Francoeur, Labelle, and Sinclair-Desgagne (2008, p. 84) note, women and ethnic minority directors “bring a fresh perspective on complex issues, and this can help correct informational biases in strategy formulation and problem solving.” Scholars argue that diverse boards are more creative and have more open discussions (Melero, 2011; Miller & Triana, 2009), which in turn may aid the organization both in dealing with complexity and improving innovativeness. Further, greater diversity may also improve access to resources (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978) that can aid the organization in a number of ways (Arfken et al., 2004; Tschirhart, Reed, Freeman, & Anker, 2009). As an example of the economic benefits of board diversity, Westphal and Milton (2000) indicate that homogeneous directors do not infuse fresh ideas into the decision-making process, thus heterogeneity is desirable. Similarly, others note that organizations with more complex environments can better understand and meet the organizations' needs by drawing on the multiple perspectives associated with adopting a more diverse board (Brammer, Millington, & Pavelin, 2007, 2009; Broadbridge, 2010). Due to these benefits of diverse boards, more complex organizations may require a variety of perspectives in the decision-making process and, therefore, adopt a more diverse board to meet this imperative (Anderson, Reeb, Upadhyay, & Zhao, 2011). Thus, economically rational reasons for having board diversity when firm complexity is high are akin to the value-in-diversity hypothesis logic (Cox & Blake, 1991) that diversity can help firms gain a competitive advantage.

Second, CEOs of complex organizations may require additional monitoring and advice from the board (Coles, Naveen, & Naveen, 2008; Klein, 1998; Yermack, 1996). Scholars suggest that minority directors may be better monitors (Adams & Ferreira, 2009; Jurkus, Park, & Woodard, 2011) due to factors such as greater focus on moral reasoning and ethical decision-making (e.g., Bear, Rahman, & Post, 2010; Post, Rahman, & Rubow, 2011) as well as lower degrees of managerial domination in the firm (Molz, 1988). Further, diversity “may promote the airing of different perspectives and reduce the probability of complacency and narrow-mindedness in a board's evaluation of executive proposals,” thus making more diverse boards better suited to monitoring and providing insight (Kosnik, 1990, p. 138).

However, in the case of firms with low operational complexity, board diversity may not be as critical. Because diversity can hinder group communication (Arrow, 1998; Lang, 1986) and lead to conflict (O'Reilly, Caldwell, & Barnett, 1989; Reagans & Zuckerman, 2001) that can be costly, there are instances when more homogenous boards are desirable (Brammer et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 1996). Thus, as Ruigrok, Peck, and Tacheva (2007, p. 555) note, “diversity in corporate boardrooms naturally leads to increased complexity in board member interactions” and therefore, organizations should not just appoint a diverse board member and “expect positive effects” but rather, should anticipate “the resulting changes in boardroom dynamics” before doing so. Since a diverse board faces communication and coordination problems, making a speedier decision less likely, combatting volatility is more difficult with a diverse board (Anderson et al., 2011). Scholars also note that the problems with respect to indecision and pluralistic ignorance in diverse boards may occur because “social homogeneity breeds, and trust is in high demand” in certain instances (Francoeur et al., 2008,p. 86). In sum, consistent with the similarity-attraction paradigm (Byrne, 1971), which describes that people are drawn to others who are like them, diverse boards can also have disadvantages with respect to team decision-making, and these disadvantages may not result in a net gain for firms low in operational complexity. Thus, economically rational perspectives suggest that organizations low in operational complexity are less likely to need and to have diverse boards. In sum, left to their own devices, operationally complex firms have reasons to want more board diversity while less operationally complex firms have reasons to want less board diversity.

1.2.2 CEO power: A social preference inhibitor of board diversity

In contrast to the research that takes an economically rational perspective to explain the antecedents to board diversity, the socially embedded view of boards suggests that board diversity is driven by social factors associated with the influence and biases of powerful decision-makers. That is, rather than considering the net benefit to the firm from having a more or less diverse board, socially embedded views contend that board diversity often reflects the personal preferences of individuals with the power to affect the composition of the board (Withers et al., 2012), particularly the CEO (Shivdasani & Yermack, 1999; Westphal & Zajac, 1995, 1997).

Two streams of research take a socially embedded view to relate the preferences of the CEO to board diversity. The first stream of research argues that CEOs may use their influence to appoint directors who are less likely to raise questions on the policies proposed by the CEO. Studies in this stream build upon research suggesting that because diverse boards are more likely to monitor the CEO, CEOs prefer less diverse boards (Westphal & Zajac, 1995, 1997). This reasoning is consistent with the similarity-attraction paradigm, which maintains that people are attracted to and have an easier time working with others similar to themselves (Byrne, 1971). Moreover, Kandel and Lazear (1992) argue that similar individuals are more likely to follow group norms and less likely to make extra efforts aimed at benefiting external constituencies. Also, having diversity may increase mutual monitoring among board members (Anderson et al., 2011). Similarly, Molz (1988) argues that minority directors are less likely to fall under the influence of management while others contend that minorities are better monitors (Adams & Ferreira, 2009; Bear et al., 2010; Post et al., 2011), suggesting that CEOs may have disutility for a diverse board and prefer more homogeneity in directors. Similarly, Hillman, Cannella, and Harris (2002) suggest that the incentive from reputation would be greater in the case of minority directors, implying that a diverse board would have more incentives to monitor the CEO effectively. In support of this contention, Nielsen and Huse (2010) find that more gender-diverse boards are associated with more strategic control. To the extent that a CEO prefers less monitoring, then, greater CEO power over the board should result in a preference for director homogeneity and thus, less diversity on the board.

The second stream of literature argues that CEOs prefer directors who are similar to themselves, and as a result, white male CEOs (the dominant demographic group among CEOs; Catalyst, 2018; Diversity, Inc., 2012; Daily, Certo, & Dalton, 1999) are associated with more homogenous boards while minority CEOs are associated with greater minority representation on the board. For instance, Westphal and Zajac (1995, 1997) studied the recruitment process of directors and concluded that CEOs systematically choose directors who have similar demographic characteristics to themselves. Such preference for similarity may be particularly strong for minority CEOs who, given their rareness and difficulties advancing to the upper echelons of organizations (O'Higgins, 2002; Zelechowski & Bilimoria, 2004), are expected to be sympathetic to the difficulties that minorities face and to assist other minorities by appointing them to boards. Similarly, Terjesen and Singh (2008) find that boards with greater diversity are more likely to hire diverse individuals to executive positions. Therefore, similar-to-me biases have been observed in the relationship between boards and the CEO. Moreover, in situations where CEOs face changes in board structure that increase the board's independence, CEOs have been found to display more ingratiation and persuasion toward board members to mitigate their loss of power (Westphal, 1998). In sum, research findings consistently indicate that CEOs proactively try to gain and keep power and to mitigate the loss of power. Next, we make predictions about how board diversity will unfold pre- and post-SOX.

1.3 The impact of SOX on drivers of board diversity

Economic drivers are those determinants that allow the board “to carry out the traditional board functions and thus positively influence governance and organizational performance” (Withers et al., 2012, p. 247). On the one hand, the value-in-diversity hypothesis (Cox & Blake, 1991) would predict that since female and ethnic minority board members bring experiences and skills to the decision-making process that are different from white male directors, more diverse boards are economically rational in instances where diverse perspectives are required. Moreover, the Post and Byron (2015) meta-analysis found that the main effect between board gender diversity and firm performance is a very small positive effect. On the other hand, the similarity-attraction paradigm (Byrne, 1971) would predict that diverse boards face communication and coordination problems that make board homogeneity economically rational when speedier decisions are necessary. Since complex firms are more likely to benefit from diverse perspectives on boards, the board composition of complex firms should adopt a make-up that is most beneficial given their needs pre-SOX (Lynall, Golden, & Hillman, 2003; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). However, research post-SOX shows that a byproduct of the legislation, which requires more outside directors on boards, has been greater board diversity (Dalton & Dalton, 2010; Zhang et al., 2013). Thus, regardless of the rational need for diversity due to high operational complexity, findings show that boards have become somewhat more diverse post-SOX. In sum, irrespective of the rational need for diversity due to firm operational complexity, we anticipate seeing more board diversity post-SOX regardless of complexity. We hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1.The positive association between firm operational complexity and board gender and ethnic diversity will disappear post-SOX.

Socially embedded antecedents to board homogeneity are those that reflect individual preferences or biases rather than those that “optimally serve the bests of the overall organization” (Withers et al., 2012, p. 255). We propose that SOX will impact the magnitude of the effect between CEO power and board diversity, because SOX and subsequent listing rules systematically reduced CEO power by making the nominating committee, and hence, the director recruitment process, independent of the CEO, and by increasing the proportion of independent directors. Further, compensation and audit committees of the board are also now fully independent of the CEO. Thus, by limiting the CEO's ability to influence board recruitment, compensation, and audit processes, and by increasing the independence of the board (Linck et al., 2008; Valenti, 2008), we expect that post-SOX CEO power, preferences, and biases will not significantly affect board composition. Therefore, firms could choose greater board diversity that may be beneficial to shareholders.

As Grosvold and Brammer (2011, p. 116) note, legislation appears to play a “significant role in shaping board diversity.” Indeed, many recent proposals to reform governance processes in countries such as the United Kingdom, Norway, and Spain have intended to increase the presence of diversity in the boardroom (Adams & Ferreira, 2009; McCann & Wheeler, 2011). In the United States, while SOX brought major changes to governance structures of publicly held organizations (Valenti, 2008; Wintoki, 2007), it did not specifically call for changes to the diversity of boards. However, scholars note that the SOX legislation and accompanying listing requirement changes have had important, unintended consequences for boards (Linck et al., 2008) and their diversity (Dalton & Dalton, 2010; Valenti, 2008). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2.The negative association between CEO power and board gender and ethnic diversity will disappear post-SOX.

2 METHOD

2.1 Sample

We examine our hypotheses using a sample of S&P 1500 firms during an 8-year period interrupted by the adoption of SOX. Data were drawn from the following sources: firm-level accounting data from COMPUSTAT, stock return data from CRSP, CEO data from ExecuComp, and director data from ISS/Risk Metrics (formerly IRRC) and BoardEX. Following previous studies (McGahan & Porter, 1997; McNamara, Aime, & Vaaler, 2005), we omit firms from utilities and financial services industries because of differences with respect to the governance of these firms (Demsetz & Lehn, 1985). Our final sample consists of 898 firms with 5,569 firm-year observations over the eight-year period from 1998 to 2005 where data for stock price, board composition, firm age, CEO tenure, and CEO age are available.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Board diversity (time t + 1)

2.2.2 Firm operational complexity (time t)

Following Johnson et al. (2013), we measure operational complexity by combining the firms' scale and scope. Using Principal Components Analysis (PCA), we create a factor with the natural log of firm assets, natural log of firm age, and the number of business segments in which a firm operates. To identify a business segment, we use data from Compustat Segment database, and we use 2-digit SIC code level to identify a unique segment. Table 1 presents factor loadings and the % of variance of all the underlying variables explained by the component that we keep. We keep only one component that had an eigenvector value of 1.55. Out of the three underlying variables that we used to create this component variable, firm age had the largest loading (0.62), whereas the diversification had the lowest loading (0.50). Overall, this component explains 52% of the variance of all the underlying variables.

| Variable | Operational complexity | CEO power |

|---|---|---|

| Firm size | 0.61 | |

| Diversification | 0.50 | |

| Firm age | 0.62 | |

| CEO tenure | 0.74 | |

| CEO duality | 0.55 | |

| Insider director ratio | 0.39 | |

| Variance explained | 0.52 | 0.55 |

| Eigenvalue | 1.55 | 1.46 |

2.2.3 CEO power (time t)

Following prior literature (e.g., Boone, Field, Karpoff, & Raheja, 2007; Linck et al., 2008), our measure of CEO power combines three indicators that are considered to affect CEO power: CEO tenure in years, if the CEO also held the position of Chairperson of the Board (i.e., CEO duality), and the ratio of employee directors on the board. These measures are somewhat similar to those used by Finkelstein (1992) and Haynes and Hillman (2010). Haynes and Hillman (2010) used an index of variables that capture the CEO's power over the board. However, we rely on principal components analysis (PCA) which minimizes attenuation bias arising out of high correlations among the underlying variables. The CEO power variable uses one component with the largest eigenvector value (1.46). The largest loading comes from CEO tenure (0.74) whereas the smallest loading comes from the ratio of employee directors (0.39). Together, the underlying variables explain over 55% of the variance (see Table 1).

SOX. We analyze the impact of SOX on the determinants of board homogeneity by creating a dummy variable with a value of 0 for years prior to the passage of SOX (before 2002), or “Pre-SOX,” and a value of 1 for subsequent “Post-SOX” years (2002 or after).

2.2.4 Controls (time t)

We incorporate several variables to control for alternative drivers of board diversity. Specifically, several characteristics of firms may affect the diversity of their board. For R&D Intensity, which indicates a desire for innovation in the firm and can lead to more diversity, we divide the firm's R&D expenditure by assets. For Firm Risk, we use the standard deviation of monthly stock returns over the previous 60 months (Coles et al., 2008). We also include Board Size, measured as the natural log of the number of directors, because larger boards could be more diverse. We control for the presence of a Woman CEO (coded 1 if the CEO is a woman and 0 otherwise) as well as Ethnic CEO (coded 1 if the CEO is an ethnic minority and 0 otherwise), which may lead to attracting or recruiting a more diverse board. We also include CEO Age measured as the natural log (Ln [CEO Age]), because being close to retirement age could affect CEO persistence for board diversity or homogeneity. To capture the value of diversity to high growth industries, we control for Industry Dynamism which is measured as the growth in sales of median firms in an industry group identified by 2-digit SIC Code every year. Lastly, we include firm fixed effects to account for the fact that some unobserved firm-specific omitted variables may affect board diversity (Arfken et al., 2004; Brammer et al., 2007).

2.3 Variables for supplemental analyses

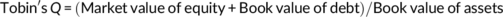

As a supplemental analysis to assess the effect of board diversity on subsequent firm performance, we measured firm performance as follows.

2.3.1 Performance (time t + 2)

3 RESULTS

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for all the variables used in our analyses. Table 3 provides correlations. The average firm in our sample has a Blau's index for heterogeneity of 0.23, indicating a high level of homogeneity. This is due to a large number of firms having white male directors only. The average firm has about 87% directors who are white males. The second largest category is white female directors at about 8% in the average firm. The ethnic male director ratio is 4%. Ethnic female directors are the least represented directors in our sample at 1%. The average board has approximately 9 members (exponent of 2.17). In our sample, 53% of firm-year observations are from the post-SOX period. The average firm in our sample spends approximately 3% of its asset value on R&D activities. A large majority of CEOs are males and only 2% of firms in this sample have a female CEO. The average age of CEOs in our sample is about 55 years.

| Variable | Mean | Median | Maximum | Minimum | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Board diversity | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.64 | −0.11 | 0.17 |

| Firm operation complexity | 0.16 | 0.01 | 3.32 | −2.32 | 1.26 |

| Industry dynamism | 0.09 | 0.09 | 1.35 | −0.24 | 0.09 |

| CEO power | 0.02 | −0.16 | 3.64 | −1.85 | 1.15 |

| Post-SOX dummy | 0.53 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 |

| R&D intensity | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Firm risk (%) | 14.44 | 12.05 | 122.48 | 3.09 | 8.56 |

| Ln (Board size) | 2.17 | 2.20 | 2.94 | 1.61 | 0.27 |

| Woman CEO | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Ethnic CEO | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| Ln (CEO age) | 4.01 | 4.03 | 4.33 | 3.69 | 0.13 |

| Ethnic female ratio | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| White female ratio | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Ethnic male ratio | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| White male ratio | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.11 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Board diversity | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 2. Firm operational complexity | 0.32** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| (0.00) | |||||||||||

| 3. Industry dynamism | −0.01 | −0.02 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| (0.70) | (0.13) | ||||||||||

| 4. CEO power | −0.15** | −0.10** | 0.04** | 1.00 | |||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||||||

| 5. Post-SOX dummy | 0.20** | 0.08** | 0.05** | −0.07** | 1.00 | ||||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||||||

| 6. R&D intensity | −0.10** | −0.19** | −0.05** | −0.04** | 0.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.77) | |||||||

| 7. Firm risk (%) | −0.22** | −0.30** | −0.03 | 0.03* | 0.03* | 0.32** | 1.00 | ||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.02) | (0.00) | ||||||

| 8. Ln (Board size) | 0.38** | 0.54** | −0.01 | −0.17** | −0.04 | −0.24** | −0.28** | 1.00 | |||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.25) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||

| 9. Woman CEO | 0.12** | −0.03** | −0.02 | −0.06** | 0.03* | 0.03* | 0.04** | −0.04** | 1.00 | ||

| (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.22) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||

| 10. Ethnic CEO | 0.12** | 0.05** | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05** | 0.02† | 0.00 | 0.05** | 1.00 | |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.49) | (0.62) | (0.48) | (0.00) | (0.09) | (0.73) | (0.00) | |||

| 11. Ln (CEO age) | 0.05** | 0.16** | 0.01 | 0.36** | 0.01 | −0.14** | −0.15** | 0.10** | −0.09** | −0.02 | 1.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.27) | (0.00) | (0.31) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.09) |

- Notes: N = 5,569; pairwise correlations. p-values are reported in parentheses below each correlation coefficient.

- † Significant at 10% level.

- * Significant at 5% level.

- ** Significant at 1% level.

Table 3 presents correlations. We see some initial evidence supporting our hypotheses from the correlations matrix. More complex firms tend to have greater board diversity (r = 0.32, p = .000) whereas firms with more powerful CEO are less diverse (r = −0.15, p = .00). These correlations provide some initial support for our arguments that firms with powerful CEOs are less likely to be associated with diverse boards while those with more complex operations are more likely to be associated with diverse boards. Powerful CEOs are less likely to be associated with a diverse board which might question the CEO's policies and might not go along with everything the top managers propose. The post-SOX dummy variable is also positively correlated with diversity (r = 0.20, p = .00), indicating an increase in the hiring of directors from diverse backgrounds. See Figure 2 for a plot of diversity over time showing years pre- and post-SOX. As you can see, average board diversity is roughly 0.20 at the time SOX was passed in 2002 but jumped to over 0.40 (more than double the amount of diversity) by 2005. It appears that the firms replaced white male directors mostly with white female directors and ethnic male directors with some change in the ratio of ethnic female directors as well.

3.1 3.1.1. The impact of firm operational complexity and CEO power on board diversity

Firm fixed effects analysis

(1)

(1)The first regression used the full sample, the second regression used a sub-sample of firms from the pre-SOX period, and the last regression used a sub-sample of firms from the post-SOX period. All the regressions included control variables, firm fixed effects, and year dummy variables. The estimated coefficients are reported in Table 4.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | Pre-SOX | Post-SOX | ||||

| Coefficient | t-stat | Coefficient | t-stat | Coefficient | t-stat | |

| Operational complexity | 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.02* | 2.01 | −0.00 | −0.06 |

| CEO power | −0.01* | −2.54 | −0.01* | −2.52 | −0.01 | −1.13 |

| R&D intensity | 0.09 | 0.87 | −0.09 | −0.86 | 0.15 | 0.56 |

| Firm risk | −0.00 | −0.77 | −0.00 | −0.49 | 0.00 | 0.61 |

| Ln (Board size) | 0.03* | 2.14 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.05† | 1.79 |

| Woman CEO | 0.01 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.81 | −0.04 | −0.64 |

| Ln (CEO age) | 0.01 | 0.61 | −0.01 | −0.50 | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| Industry dynamism | 0.01 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 1.11 | 0.01 | 0.25 |

| Ethnic CEO | −0.01 | −0.33 | 0.01 | 0.66 | −0.07 | −0.97 |

| Post-SOX dummy | 0.19** | 40.44 | ||||

| Constant | 0.28** | 3.46 | 0.26* | 2.49 | 0.24 | 0.89 |

| Year and firm fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Observations | 5,569 | 2,950 | 2,619 | |||

| R-squared | 0.481 | 0.067 | 0.521 | |||

- Note: Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented.

- † Significant at 10% level.

- * Significant at 5% level.

- ** Significant at 1% level.

Results in column 1 of Table 4 show that firms with a powerful CEO are less likely to have a diverse board. The coefficient of CEO Power in this column is −0.01 and it is significant at the 5% level (t-stat = −2.54). The coefficient of Firm Operational Complexity is positive but insignificant in column 1. However, when we examine the effects of these variables in pre-SOX and post-SOX sub-samples in columns 3 and 5, respectively, we find that both Firm Operational Complexity and CEO Power variables are significant in the pre-SOX period but they are not significant in the post-SOX period. Column 3 presents results for the pre-SOX period. The coefficient of CEO Power is −.01 and it is significant at the 5% level (t-stat = −2.52). The coefficient of Firm Operational Complexity in column 3 is 0.02 and significant at the 5% level (t-stat = 2.01). Both Firm Operational Complexity and CEO Power variables are not significant in column 5 indicating that these two variables lose their significant associations with board diversity post-SOX. These results are consistent with Hypotheses 1 and 2.

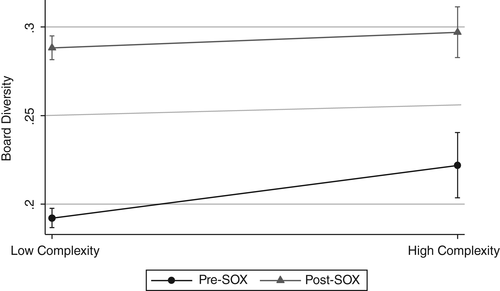

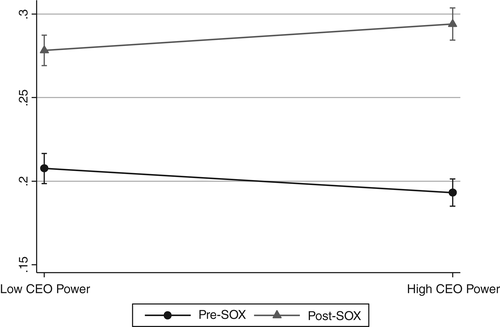

3.1 Supplemental analyses

In Table 5, we conduct the analyses using interactions of the SOX indicator with the primary variables of interest in this study. This allows us to test the entire data set together and plot the shapes of the interaction effects. In column 1 of Table 5, we find that the coefficient on Operational Complexity is positive and marginally significant (at the 10% level, b = 0.01, t-stat = 1.71). However, the interaction term Operational Complexity × Post-SOX is negative and statistically significant (at 1% level, b = −0.02, t-stat = −5.28). We plotted the interaction effect following Aiken and West (1991) such that operational complexity is plotted at plus and minus one standard deviation from the mean for high and low values, respectively. The interaction term (see Figure 3) shows that the effect of operational complexity on board diversity diminishes in the post-SOX period, which is consistent with Hypothesis 1. The coefficient on CEO Power in column 1 of Table 5 is negative and statistically significant (at the 5% level, b = −0.01, t-stat = −2.37) but the coefficient on the interaction term CEO Power × Post-SOX is positive and statically significant (at the 5% level, b = 0.01, t-stat = 1.97). For a plot of the interaction, see Figure 4. These results suggest that powerful CEOs were negatively associated with board diversity in the pre-SOX period but this association reverses post-SOX. These results are consistent with Hypothesis 2.

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Diversity(t + 1) | ||

| Coefficient | t-stat | |

| Operational complexity | 0.01† | 1.71 |

| CEO power | −0.01* | −2.37 |

| R&D intensity | 0.06 | 0.59 |

| Firm risk | −0.00 | −0.54 |

| Ln (Board size) | 0.02 | 1.26 |

| Woman CEO | 0.01 | 0.64 |

| Ln (CEO age) | 0.01 | 0.53 |

| Industry dynamism | −0.01 | −0.55 |

| Ethnic CEO | −0.00 | −0.12 |

| Post-SOX dummy | 0.18** | 26.06 |

| Operational complexity × Post-SOX dummy | −0.02** | −5.28 |

| Industry dynamism × Post-SOX dummy | 0.11** | 3.26 |

| CEO power × Post-SOX dummy | 0.01* | 1.97 |

| Constant | 0.18* | 2.03 |

| Year and firm fixed effects | Yes | |

| Observations | 5,569 | |

| R-squared | 0.499 | |

- Note: Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented.

- † Significant at 10% level.

- * Significant at 5% level.

- ** Significant at 1% level.

For robustness, we conduct analyses using additional control variables (results available upon request) and find consistent results. Specifically, we used the count of directors to measure board size, we used a two-thirds majority of independent directors for a board independence majority, and we used the number of inside directors as a measure of board composition. The results of these robustness checks are consistent with those we reported before. To test the sensitivity of our analysis to serial correlation and to the impacts of outliers and influential observations, we use several alternative techniques. First, we repeated the tests using a random effects model, year-by-year regressions, and the year-by-year results in the Fama-MacBeth procedure (Fama & MacBeth, 1973). All three approaches produce similar results. To examine whether outliers and influential observations had any effect on the results, we repeated the basic regressions with all the variables winsorized at 3% and 97%. The results remained consistent. In addition, using least median deviation regressions also yielded similar results. Some researchers argue that since there is low variability in board homogeneity over the cross-sections, a firm fixed-effects may not be appropriate for this study (Coles et al., 2008; Hermalin & Weisbach, 1998). To address this concern, we used industry fixed effects based on 2-digit SIC codes and found similar results.

In addition, to determine the association between board diversity and firm performance as an exploratory analysis, we ran an analysis predicting firm performance both pre- and post-SOX. We measured firm performance in two ways: market-based performance as Tobin's Q (at time t + 2), and accounting-based performance as return on assets (at time t + 2). We found no statistically significant main effects of board diversity predicting firm performance either before or after the passage of SOX. Therefore, while the increase in board diversity is not positively associated with firm performance, it is also not negatively associated with firm performance. It simply has no association with firm performance. Therefore, SOX appears to be a win for board diversity overall, because it improves equal opportunity for different types of directors to serve on boards while having no association with firm performance. Details of the supplemental test results are shown in Appendix A.

We also used a difference-in-difference approach (e.g., Seierstad, Healy, Goldeng, & Fjellvær, 2020) to observe firms that did not meet the board independence criteria at the end of 2001 as was eventually mandated by SOX (2002) and subsequent exchange listing rules. These companies formed the treatment group and we compared them with the control group of firms that met the SOX related board independence criteria in 2001. We created a dummy variable (non-compliant) that takes a value of 1 for treatment firms and 0 for control firms. To compare how board diversity changed between these two groups following SOX, we used the interaction term Non-compliant × Post-SOX and ran a firm fixed-effects regression similar to column 1 of Table 3. Results from this analysis are presented in Appendix B. We found a positive coefficient on Non-compliant × Post-SOX, which is marginally significant at the 10% level. We also found a negative coefficient on CEO power which is significant at the 10% level. These results indicated that those firms that were forced to increase board independence due to SOX hired more diverse directors as compared with the control group.

Finally, in order to ensure that our non-statistically significant results are not due to a lack of power to detect effects (i.e., a Type II error), we conducted our regression analyses including formal tests of power. Results show that power is above 99% for the analyses presented in Tables 3 and 4.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Theoretical implications

Our study offers multiple contributions to theory and research on boards of directors and corporate governance. Theoretically, the results show support for similarity-attraction theory (Byrne, 1971) because CEO power is negatively and significantly related to board diversity pre-SOX, implying a similar-to-me bias. However, this effect disappeared post-SOX, which means that powerful CEOs had less power to shape board composition and their boards became more diverse. This supports the notion that CEOs who like to surround themselves with others who have things in common with them (Westphal & Zajac, 1995) in the pre-SOX period are restrained by SOX-related mandates. The findings also extend similarity-attraction research which has overwhelmingly concluded that similar-to-me effects are very robust. Specifically, the results suggest that in order to break the similar-to-me bias, government regulation is helpful to obtain a more diverse board.

However, the pattern of results and implications for research are less clear with respect to the value-in-diversity hypothesis (Cox & Blake, 1991). The results are supportive of the value-in-diversity hypothesis in that pre-SOX the operationally complex firms are significantly associated with greater board diversity. This implies that operationally complex firms seek diversity, presumably because they believe it will help them function better. However, this effect disappeared post-SOX, possibly because firms became more diverse after SOX regardless of their operational complexity. These findings support the value-in-diversity hypothesis, because pre-SOX operationally complex firms have a good reason to want more diversity to help them understand their complex environment. However, contrary to the value-in-diversity hypothesis, the supplemental analyses showed no significant association between board diversity and firm performance either pre- or post-SOX. This extends the value-in-diversity hypothesis by demonstrating that new legislation like SOX may indirectly result in more board diversity whether the firm has a compelling operational need for a diverse board or not. In that case, more diversity may not lead to better business performance but simply the same level of performance.

The finding that SOX affected different drivers of board diversity is insightful to the literature on the antecedents of board composition. The finding that economically rational factors promoting board diversity pre-SOX disappeared post-SOX suggests that firms are responding to regulatory requirements as imposed by exogenous legislative shocks. Results also show that exogenous shocks (i.e., new laws) are effective at influencing the effect of certain social preference drivers against board diversity tied to CEO power. These findings answer calls for research on the drivers of board diversity (e.g., Johnson et al., 2013; Kang, Ding, & Charoenwong, 2010) and understanding how governmental legislation can play a role in bringing about different compositions of boards (e.g., Kanagaretnam, Mestelman, Nainar, & Shehata, 2010; Linck et al., 2008; Withers et al., 2012).

4.2 Practical implications

This study is also insightful for practice. Each year, organizations such as the Hispanic Association on Corporate Responsibility, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Catalyst, and others conduct widely publicized studies and ratings that highlight boardroom diversity as an important element in assessing leadership and corporate governance. In addition, board diversity is often mentioned in media recognition lists (such as Fortune magazine's “50 Best Companies in America for Asians, Blacks, and Hispanics”) as one criterion in assessing companies' commitment to workplace diversity. Also, the topic of diversity on corporate boards is often the subject of articles in the popular press. Such calls from various stakeholders to make boards more diverse have likely played a role in the United Kingdom, Norway, and Spain, among others, enacting legislation to mandate gender and ethnic diversity on corporate boards (Adams & Ferreira, 2009; Catalyst, 2014; Grosvold & Brammer, 2011). The academic literature on boards has followed the public interest in boards' gender and ethnic diversity to address what factors may be driving homogeneity and the collective benefits of heterogeneity (e.g., Adams & Ferreira, 2009; Bear et al., 2010; Post et al., 2011). Despite these efforts, it remained unclear what effect of one of the most important legislative acts, the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX), had on board diversity. In this paper, we empirically investigate drivers of board diversity and how their effects changed with the passage of SOX. We find that both economically rational predictors of board diversity (i.e., operational complexity) based upon whether diversity will benefit the organization (Withers et al., 2012), and social preference drivers against board diversity (i.e, CEO power) disappear post-SOX.

These findings suggest that firms with greater need for diversity lose flexibility to configure diverse boards as they choose post-SOX, as the effect of operational complexity on board diversity loses statistical significance post-SOX. Complex firms appear to want diversity all along, but lose some control post-SOX. After SOX, the less complex firms also have more diversity as a byproduct of SOX. Moreover, the finding that the negative and statistically significant effect of CEO power on board diversity disappears after SOX indicates that legislation may be the only way to get powerful CEOs to have more diverse boards of directors. In 2018, California became the first state in the United States to require publicly traded companies based in that state to have at least one woman on their board (Wamsley, 2018). Our findings suggest that the most direct and efficient way to change a company's behavior is through legislation.

Various stakeholders lament the lack of practical guidance on governance issues (Daily et al., 2003; Dowell et al., 2011). This is particularly true coming off of the “Great Recession” in which outdated governance practices have been cited as playing a role and, subsequently, calls for reform were made. The present study offers insights with respect to exogenous shocks and regulatory changes that may affect board diversity. Specifically, the findings of this study suggest that when a company is left to its own devices, economic drivers may be beneficial for board diversity but CEOs' personal preferences may not. These effects were both reduced and no longer significant post-SOX, which means the SOX legislation was a double-edged sword for diversity. On the one hand, the logical/economically rational drivers of diversity on boards were mitigated which does not seem helpful. However, on the other hand, the social preference/personal bias factors associated with CEO power were also reduced, which does seem helpful for boards and board diversity. Thus, legislators may consider whether the economic rationale for the legislation is compelling while also addressing how to avoid bias of decision-makers, perhaps with specific mandates for diversity as was done in other countries (Catalyst, 2014).

These findings have implications for CEOs as well human resources (HR) leaders. For CEOs, our findings imply that they cannot always do what they want in organizations because national laws restrict their actions. This can be good or bad from a CEO's perspective, because sometimes it gives them a mechanism to do things that organizations really need, but other times it prevents CEOs from doing things that could be in their personal interests more so than the interests of the organization. CEOs must operate within the boundaries of what they can do given governance laws and their fiduciary responsibilities imposed by the business environment. For HR leaders, our findings suggest that sometimes their superiors are doing things that benefit themselves but not the greater good of the organization. Because human resources is tasked with compliance to employment laws, providing equal opportunity employment, maintaining employee well-being, and managing employees to increase organizational productivity, they have many competing interests. Moreover, HR leaders report to the CEO and members of his/her top management team which means that there is a power differential and they will not always be able to stop CEOs whose policies benefit themselves more so than the organization. This means that it is important for HR leaders to persist in doing what they think is right for the employees and the organization and to justify their recommendations by linking them to overall organizational health and productivity, especially when those suggestions may not be very popular among senior leaders. Moreover, our findings suggest that the human resources function should be seen as a strategic partner role rather than a tactical role (or even one that can even be outsourced), because having HR leadership in a CEO's top management team can help him or her consistently adhere to policies that promote equal employment opportunity, the ethical treatment of employees, and overall organizational health and productivity in the long run.

We now turn to a different implication, namely that the matter of state and national quotas for corporate boards is perhaps most salient in the context of white male-dominated corporate boards that may intentionally or unintentionally select directors most similar to themselves, limiting opportunities for female and ethnic minority directors. Therefore, there is an ethical and moral case to be made for legislation that encourages equal opportunity of all groups to advance to prestigious board positions. However, in an article published in 2018, The Economist concluded its review of the 10-year period after Norway's quota requiring 40% women directors by stating “Gender quotas at board level in Europe have done little to boost corporate performance or to help women lower down.” The article further suggests that the newly recruited women directors often lack the “… management experience that makes a good board director.” It is important to note that if several women were added to the board and firm performance did not decline, the new women directors seem no worse than the directors who were there before (i.e., more women came in but performance stayed the same). The Norwegian quota was implemented to increase diversity (i.e., representation of women) on boards of directions, so if diversity increased while having a neutral effect on firm performance, the legislation appears to have succeeded.

While Norway was the first country to implement a quota for the representation of women on boards in 2003, many European countries have followed. Spain implemented a quota in 2007, Iceland in 2010, France and Belgium in 2011, Italy in 2012, the Netherlands in 2013, Germany in 2015, and Portugal and Austria in 2017 (Mateos de Cabo, Terjesen, Escot, & Gimeno, 2019). Although it is too soon to tell the outcome for the laws passed within the last few years, we identified a recent study which looked at diversity on boards of directors in Spain pre and post the quota implemented by the 2007 Spanish Gender Equality Act (Mateos de Cabo et al., 2019). The authors explain that the Spanish quota implemented in 2007 was a soft quota, meaning that the government has no enforcement penalties in place if firms fail to meet the recommended 40% target of each gender to serve as board directors. The Spanish government did provide one incentive to firms that meet the quota by saying that quota compliant firms may receive preference for public contracts. This is in contrast to the hard quota implemented by Norway in 2003, which requires boards to be comprised of at least 40% of each gender by 2008 or face stiff consequences including delisting, nonregistration, and paying fines. Mateos de Cabo et al. (2019) found no significant increase in the number of women on boards of directors in Spain overall, but there was an increase for firms that use public contracts. Moreover, for those firms that increased the representation of women on boards, there was no statistically significant change in income for those firms. Mateos de Cabo et al. (2019) conclude that the Spanish government is not committed to the quota and that without enforcement there will be no substantial change. Therefore, similar to the findings in Norway, the Spanish quota provided more opportunity for women to be represented on boards of firms with public contracts and it made no difference in the firms' financial performance. Once again, it appears that quotas have a neutral effect on firm performance, but when they are coupled with a government enforced punishment for a lack of compliance with the quota, they are effective at introducing equal opportunity for both men and women to serve on boards of directors.

This brings us to a greater ethical and philosophical question with respect to diversity on boards. Is board diversity held to a higher standard than board homogeneity? When board diversity increases, people often wonder whether diversity increased firm performance (Grosvold & Brammer, 2011), and they may even conclude that diversity is not that helpful if firm performance does not increase after the board becomes more diverse. Does the performance bar move higher such that the board is being held to a higher standard when it becomes more diverse? If the board had become less diverse, would people expect to see a homogeneity premium in firm performance to demonstrate that a homogenous board is better than a diverse board? Theoretical research proposes a double standard of competence whereby women leaders are evaluated more harshly than men leaders because of double standards favoring men (Foschi, 1996, 2000). Empirical research supports that this is true (Castilla, 2012) and that the disadvantages women face in evaluations compared to men grow larger among star performers (Aguinis, Ji, & Joo, 2018). Moreover, research shows that gender bias is pervasive and usually deeply (i.e., subconsciously) embedded. Nosek et al. (2007) reported finding that, in a study with over 2.5 million participants, 76% of participants subconsciously associated males with careers and females with family. Might these subconscious biases affect who we nominate to boards and whether women are viewed with greater skepticism and held to higher standards (i.e., increased firm performance)? Organizations may wish to consider whether biases could be at work in affecting the demographic composition of boards and in how diverse boards are evaluated. A key question for consideration is whether board diversity is being held to the same standard as board homogeneity or whether the bar moves higher when diversity is evaluated.

4.3 Limitations and future research

One limitation of this study is that we do not measure the job-related qualifications of directors to serve on boards both pre- and post-SOX. Our supplemental analyses showed no effects of board diversity on firm performance either pre- or post-SOX, but we do not know why this is the case. The value-in-diversity hypothesis would argue that firm performance should be better if boards are diverse (Cox & Blake, 1991). However, the similarity-attraction paradigm would predict that diversity among team members could reduce the quality of interpersonal dynamics which can make the board less effective (Byrne, 1971). Could both positive and negative forces be at work on diverse boards simultaneously and then cancel each other out to produce no effect on firm performance? Future research should aim to measure variables including individual qualifications, information elaboration, and interpersonal dynamics/team process to determine whether that is the case.

Moreover, it would be interesting to further probe the processes by which CEOs with high power may directly or indirectly influence board diversity. If the CEO is powerful and tries to influence board appointments to include their acquaintances who will be supportive of their decisions, that may create a knowledge gap on the board. In theory, if the power of CEOs to influence board diversity has been reduced post-SOX, then perhaps we should see less nepotism on boards and more selection based on the required qualifications. If that is the case, then perhaps the performance of boards and their ability to advise the firm would improve over time and enhance firm performance, as boards have been shown to influence firm strategy (Deutsch, 2005). However, an influx of outside directors post-SOX who are less familiar with the firm's inner workings may also result in less valuable advice to the firm for a period of time until the directors become more familiar with the business and its environment. This implies that more longitudinal research is needed to examine the ways in which board diversity helps organizations be more effective and the challenges that diverse boards face in fulfilling their obligations to monitor, advise, and provide resources to the firm. If such data were available to researchers, that would help open the black box (Lawrence, 1997) of intervening processes that can explain the interesting findings presented in this study.

Additionally, future research can test whether the results of our study examining board diversity in the form of gender and racial/ethnic diversity generalize to other forms of diversity on boards, such as disability. For example, a bibliographic search in Psychological Abstracts (Psycinfo) and Business Source Complete for “board of directors” and “disability” in the abstract of papers reveals that these subjects have not been investigated together. Of the 14 results from the search, 13 of the articles dealt with topics discussed by boards of directors of major medical, social services, and other organizations dealing with identifying disabilities, accommodating disabilities, and providing services to people with disabilities. The remaining article was a short opinion piece written by a person with a disability who serves on a board of directors. Despite the fact that an estimated 12.8% of the US population has a disability (Institute on Disability, 2017), we did not identify a single research paper which examines people with disabilities as resources who serve on boards of directors. One reason for this may be that there is a lack of data on director disability, which suggests that data vendors such as Board EX or ISS/Risk Metrics could perhaps try to collect such data in the future. Researchers who send surveys to boards of directors could also try to collect such information. It is possible that the passage of SOX may have created a context that provides more opportunity for people with disabilities to serve on boards of directors, and it would be interesting to know how many people currently serve on boards of directors who identify as having a disability as well as how many served pre-SOX.

5 CONCLUSION

We examined how the enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX, 2002) affected the relationships between economically rational and social preference drivers of board diversity. In a sample of S&P 1500 firms drawn over an eight-year period during which SOX was passed, we find that SOX is positively associated with board diversity. Firm operational complexity is positively and significantly associated with board diversity pre-SOX, while CEO power is negatively and significantly associated with board diversity pre-SOX. Both of these effects disappear post-SOX, which implies a double-edged nature of SOX on firms. On the one hand, the legislation limits the economically rational predictors of board diversity, because post-SOX firms generally became more diverse. On the other hand, SOX successfully limited the social preference bias that powerful CEOs have to reduce diversity on the board of directors. We find that board diversity has no association with firm performance either pre- or post-SOX. These findings offer insight with respect to how legislation affects diversity on corporate boards and add to our knowledge regarding drivers of board diversity.

Appendix A.:

(2)

(2)| Panel A: Regressions of firm performance on Board Diversity with the moderating role of SOX | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (Pre-SOX) | (Post-SOX) | ||

| Tobin's Q(t + 2) | ||||

| Coefficient | t-stat | Coefficient | t-stat | |

| Board diversity(t + 1) | −0.25 | −0.88 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Operational complexity | −0.38** | −5.88 | −0.11† | −1.87 |

| CEO power | 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.05† | 1.73 |

| R&D intensity | 4.88** | 3.62 | 0.61 | 0.69 |

| Firm risk | −0.09** | −7.75 | −0.00 | −0.49 |

| Ln (Board size) | −0.50** | −2.85 | −0.20† | −1.67 |

| Woman CEO | 0.37 | 1.29 | 0.36 | 1.54 |

| Ln (CEO age) | −0.33 | −1.09 | −0.21 | −0.84 |

| Industry dynamism | 0.29† | 1.74 | 0.30† | 1.75 |

| Ethnic CEO | −0.20 | −0.79 | 0.20 | 0.77 |

| Constant | 5.49** | 4.38 | 3.43** | 3.26 |

| Year and firm fixed effects | Yes | Yes | ||

| Observations | 2,938 | 2,631 | ||

| R-squared | 0.191 | 0.110 | ||

| Panel B: Regressions of firm profitability on board diversity with the moderating role of SOX | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (Pre-SOX) | (Post-SOX) | ||

| ROA(t + 2) | ||||

| Coefficient | t-stat | Coefficient | t-stat | |

| Board diversity(t + 1) | −0.01 | −0.565 | 0.01 | 0.659 |

| Operational complexity | −0.00 | −0.417 | −0.00 | −0.494 |

| CEO power | 0.37** | 4.369 | 0.11 | 1.604 |

| R&D intensity | −0.00** | −3.345 | 0.00** | 2.871 |

| Firm risk | −0.00 | −0.219 | −0.00 | −0.407 |

| Ln (Board size) | −0.00 | −0.016 | 0.01 | 0.264 |

| Woman CEO | −0.02 | −1.217 | 0.02 | 0.909 |

| Ln (CEO age) | 0.06** | 5.116 | 0.10** | 7.555 |

| Industry dynamism | −0.01** | −2.759 | −0.00 | −0.125 |

| Ethnic CEO | −0.00 | −0.290 | 0.03 | 1.270 |

| Constant | 0.21** | 2.673 | −0.01 | −0.086 |

| Year and firm fixed effects | ||||

| Observations | 2,947 | 2,618 | ||

| R-squared | 0.158 | 0.102 | ||

- Note: Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented. †Significant at 10% level. * Significant at 5% level. ** Significant at 1% level.

Appendix B: Difference-in-difference estimation of Board Diversity with the moderating role of SOX

| Board diversity(t + 1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t-stat | |

| Non-compliant × Post-SOX dummy | 0.02† | 1.737 |

| Operational complexity | 0.01 | 0.830 |

| CEO power | −0.01† | −1.832 |

| R&D intensity | 0.06 | 0.512 |

| Firm risk | −0.00 | −1.033 |

| Ln (Board size) | 0.02 | 1.013 |

| Woman CEO | 0.01 | 0.255 |

| Ln (CEO age) | 0.01 | 0.370 |

| Industry dynamism | 0.01 | 0.694 |

| Ethnic CEO | 0.01 | 0.338 |

| Constant | 0.36** | 2.841 |

| Year and firm fixed effects | Yes | |

| Observations | 4,522 | |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.473 | |

- Note: Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented. †Significant at 10% level. * Significant at 5% level. ** Significant at 1% level.

Biographies

Dr Arun Upadhyay is in the College of Business at Florida International University. Dr Upadhyay's research focuses on corporate governance issues. He studies corporate leadership structure, financial reporting and executive compensation. He has published numerous articles on these topics. His work has been presented at various national and international conferences.

Dr María Triana is a Professor at Vanderbilt University in the Organization Studies area within the Owen Graduate School of Management. She earned a PhD in Organizational Behavior and Human Resources with a minor in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from Texas A&M University. María's research interests include diversity and discrimination in organizations.