The operationalisation of recovery colleges: A scoping review

Abstract

Background

Recovery Colleges (RCs) represent an approach to enhancing mental wellbeing through education, lived experience and co-production. Despite their increasing presence, scant literature explores the operationalisation of RCs and their embodiment of co-production principles. The aim of this scoping review was to investigate the operationalisation of RCs and their application of co-production in RCs located in high-income countries over the past decade.

Methods

Employing an established scoping review methodology, searches were conducted across seven academic databases. Ten primary studies met the inclusion criteria. In addition, stakeholders were consulted to validate themes and uncover knowledge gaps.

Results

Findings suggest that RCs are inherently idiosyncratic, adapted to suit local contexts. Discussions persist regarding their optimal institutional contexts and positioning and the interpretation of key terms such as ‘recovery’ and ‘co-production’, influencing daily operations and stakeholder involvement. Challenges surrounding measuring success against fidelity criteria underscore the need for a broader understanding of RC value and sustainability.

Conclusion

This review offers a synopsis of the existing literature offering insights concerning the operationalisation of RCs. Through a synthesis of diverse primary studies, it systematically identifies and describes the operational nuances within the RC landscape and the fundamental elements underpinning RC operations, while shedding light on critical knowledge gaps in both research and practice.

So What?

This review underscores the importance of a broader understanding of RC value and sustainability, offering insights for both research and practice in the field of mental health and wellbeing. This review highlights the significance of further exploration and refinement of RC operationalisation to enhance their effectiveness and impact in supporting mental wellbeing.

1 INTRODUCTION

Historically, services for the management of people experiencing ‘mental illnesses’ were characterised by coercive measures, restraint, and institutionalisation, which often hindered individuals from full societal participation.1 Traditional approaches to mental health service provision face enduring criticism due to their deficit-oriented nature,2 lack of comprehensiveness3 and failure to recognise the contributions of consumers with lived experience.4

Internationally, there have been widespread calls for a paradigm shift in the delivery of mental health services1, 5 that better address the population's mental health needs.1, 3 Subsequently, over the past two decades, mental health policy and service delivery have undergone changes, increasingly emphasising the concept of recovery and recovery-oriented practices.3, 6, 7

Recovery-oriented practices signify a departure from a biomedical model, which according to Slade,8 oversimplifies and disregards context and lived experiences influenced by social and structural factors. Instead, the focus is on supporting individuals to access resources to achieve a quality life, often termed ‘recovery’,9 as well as recognising the importance of enabling everyone to participate in society, free from prejudice and with equal citizenship.10 There is consensus regarding the role of consumers in recovery-oriented practices, accentuating the provision of support and active engagement in their personal journey towards wellbeing and a meaningful life.11, 12 This approach also underscores individuals' autonomy in decision-making, which includes their control over service selection.4

Recovery-oriented approaches, underpinned by mental health policies, have had a transformative impact globally, for example, The World Health Organisation Mental Health Action Plan for 2013–2020,13 The Australian National Mental Health Policy14 and The Australian Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan.15 However, the implementation of this recovery-orientated approach has posed challenges, necessitating changes in organisational practices to genuinely fulfil documented commitments.7 This includes involving consumers in the planning and delivery of mental health services.16 The adoption of recovery-oriented practices is also hindered by various interpretations of recovery,6 particularly in the medical environment, where it often implies ‘being cured’ or having no ‘symptoms’.8 Ongoing difficulty in reconciling the concepts of ‘clinical’ and ‘personal’ recovery17 continues to affect the understanding of recovery and how to develop and deliver ‘recovery-oriented services’.6 Nevertheless, the generational shift introduced by the recovery movement has refocused attention on individual wellbeing and participation.18

Recovery Colleges (RCs) are educational centres designed to help mental health recovery by shifting the focus from treatment to education, to support individuals living with mental distress, reduced social capital and connection to community.7 Within the college environment students, and educators, engage in a different kind of relationships. They are regarded as equals who learn together,19-21 exchanging skills and expertise. While the global number of RCs remains uncertain, recent research by Hayes et al.2 observed that there were 221 RCs operating in 28 countries across five continents. However, no official accrediting body oversees RCs, nor is there a universal delivery model.19

Principles guiding the operations of RCs, also referred to as fidelity criteria, were initially established by Perkins and colleagues,12 and subsequently refined and expanded by others.22, 23 While fidelity has been used to measure and evaluate mental health interventions,24-26 there is a scarcity of research focused on investigating the correlation between fidelity and outcomes in RCs.24 The available evidence regarding the reliability, validity, and effectiveness of RCs based on fidelity criteria is minimal, which may stem from the necessity for RCs to tailor their approaches to local contexts and address the varied needs of individuals.19, 27 A notable gap in current knowledge pertains to the specific criteria deemed crucial for the effective implementation of RCs and whether fidelity criteria indeed represent the optimal measure of success. A recent global study assessing the Recollect Fidelity Criteria in RCs reported high fidelity, particularly among RCs located outside Asia,2 this was especially so in the areas of equality, commitment to recovery, being available and being progressive. However, there is limited data on how fidelity relates to student outcomes, which underscores uncertainty regarding the association between fidelity and outcomes. Broadly, the fidelity criteria of RCs emphasise strengths, support pathways for further education and employment, while prioritising inclusivity and accessibility. The approach highlights the importance of providing students access to personal educational support tailored to their unique needs. It is essential to note that RCs are not intended to replace mainstream assessment and treatment services or serve as substitutes for traditional education but offer an alternative pathway. Consequently, the specific criteria contributing to the successful operationalisation of RCs remain unclear.

Co-production promotes collaboration and shared decision-making12 and is a central tenet of RCs,28 involving service users and providers to design and deliver services by sharing expertise. This approach recognises the value of experiential knowledge and aims to create equitable partnerships by assigning equal importance to diverse forms of expertise.20, 29, 30 Co-production challenges traditional hierarchical dynamics by neutralising power imbalances by not privileging one perspective over another.21, 30, 31 While acknowledged for its transformative potential,9 there is a lack of specific literature on co-production implementation in RCs.

Given the proliferation of RCs globally, there has been surprisingly limited research on their key operational workings.23 Existing literature on the practical implementation of fidelity criteria, which includes co-production in RCs is scarce.20 Understanding how fidelity criteria are applied in RCs is crucial for improving comprehension, reproducibility and empirical support of their operationalisation.2 This scoping review investigates the operationalisation of RCs and their co-production practices in high-income countries over the past decade. For clarity and reference please refer Appendix A for terminology and definitions of terms adopted in this paper.

2 METHODS

The Joanna Briggs Institute Methodology for Scoping Reviews PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)32 and the Arksey and O'Malley33 methodological framework34 guided this review. The review employed the following stages: (i) identifying the research question; (ii) identifying relevant studies; (iii) selection; (iv) charting the data; (v) collating, summarising and reporting the results and (vi) stakeholder consultation. The consultation stage aimed to provide additional information and perspectives outside the published literature. Human Research Ethics Committee approval (number HRE2023-0214) was obtained.

2.1 Identifying the research question

A preliminary literature search was undertaken to identify existing reviews and to assess the extent and volume of current evidence to inform this review's aim. The literature search methodology adhered to the inclusion criteria outlined in Table 1, ensuring a comprehensive selection of relevant studies for analysis. No studies were identified that examined the daily operations of RCs and/or initiation and implementation of co-production practices.

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| Full text. |

| Quantitative and qualitative study designs. |

| Primary studies. |

| Peer-reviewed literature and grey literature. |

| Published between 2013 and 2023. |

| English language. |

| High-income countries. |

| Established, discussed and/or evaluated organisational or contextual criteria of operating a RC (i.e., fidelity criteria, co-production, resource management) |

Studies were excluded if they focused on a specific context within the RCs setting, that is, dementia and homelessness. Given the Australian focus of this review, the timeframe (2013–2023) was selected to correspond with the establishment of the first RC in Australia in 2012.

2.2 Identifying relevant studies

Seven databases were searched for published, peer-reviewed literature: Embase, CINHAL, ProQuest, Medline, PsycINFO, Emcare and Scopus. A grey literature search was conducted via ProQuest Dissertations and Theses and Google Scholar, using the same search terms (Table 2).

| Concept 1 | Concept 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Keywords | ‘recovery college*’ OR ‘recovery academ*’ OR ‘recovery education’ or ‘discovery college*’ | HICs |

2.3 Selecting studies

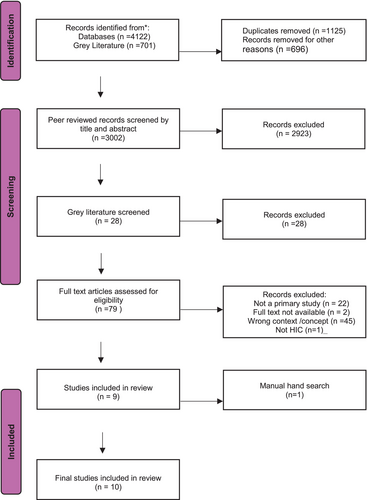

Identified citations (n = 4122) were extracted into EndNote 20 and duplicates were removed (n = 1125). Article titles and abstracts (n = 3002) were screened. The remaining articles (n = 79) were retrieved in full and imported into Rayyan. Full-text screening of the remaining articles was undertaken35 by two independent reviewers. A third reviewer was engaged where there was any disagreement to achieve consensus. Following a full-text review, 70 records were excluded. Manual hand searching was conducted of all reference lists of included studies to identify additional literature (Figure 1).

2.4 Charting the data

Selected articles were charted using a descriptive-numerical approach34 (Table S1; Box 1).

BOX 1. Data extraction table characteristics

- Reference

- Study aim

- Country/sector

- Sample (e.g., setting, study population, sample size)

- Study design (e.g., sampling strategy, data collection, ethics)

- Operational and contextual information (operations, funding source, RC descriptives, reason(s) for establishment, co-production descriptives, recovery descriptives, fidelity criteria descriptives)

- Outcomes (against the review objectives), study limitations and recommendations

2.5 Collating the data

Following the development of the data extraction table, key content for further description was transferred into a Word document and narrative descriptions were created. Each of the included papers was discussed in detail with the entire research team and reviewed during consultation.

2.6 Fidelity criteria

Studies were assessed to determine the reporting of fidelity criteria underpinning RC operations. A yes/no checklist was used to identify the inclusion of the criterion. Please refer to Table 6.

2.7 Consultation

Consultation via semi-structured interviews using Microsoft Teams was conducted with authors of the included articles, providing methodological rigour in validating findings.34 The corresponding authors of each included article (n = 8) were invited via email to participate in an interview. The interviews explored the author's understanding of recovery, co-production and the requirements for the successful implementation of RCs. Narrative summaries and quotes from the consultation were used to illustrate the findings.

3 RESULTS

Ten studies were included in the final review. Four authors responded to the request to participate in the study and three were interviewed.

3.1 Overview of characteristics of the included studies

Eight studies2, 19, 22, 27, 28, 36-38 were conducted in the United Kingdom and two in Australia.9, 21 Five studies9, 19, 21, 22, 27 were situated in the mental health sector and three2, 37, 38 did not specify sector. King and Meddings36 indicated a variety of sectors, with the majority located within the healthcare sector (52%). Zucchelli and Skinner28 reported healthcare settings, nominating mental health as the most appropriate sector for RCs to be located.

3.2 Sample

Four studies19, 22, 27, 37 operated out of Mental Health Trust bases, which are organisational entities within the UK National Health Service responsible for mental health service provision. Two studies9, 21 operated within existing clinical mental health services, the remaining four2, 28, 36, 38 did not specify their RC location.

Six studies9, 19, 21, 22, 27, 37 examined the perspectives of RC staff and students, while one study2 included RC managers only. King and Meddings36 used existing RC networks such as the Recovery College International Community of Practice and ImROC, while Zucchelli and Skinner28 gathered insights from students, staff and other Trust staff involved in RC operations. In the remaining study Meddings et al.38 gathered reflections of stakeholders involved in developing a RC pilot. Study sample sizes ranged from 1137 to 63 participants.2 Three studies22, 28, 38 did not state their sample size.

3.3 Study design

Four studies2, 19, 27, 37 used purposive sampling and one employed snowball sampling.36 The remaining studies (n = 5) did not report sampling methods.9, 21, 22, 28, 38 Most studies used qualitative methods (n = 6).19, 22, 27, 28, 37, 38 Three studies9, 21, 36 used mixed methods (e.g., interviews with a survey) and one study used a quantitative hierarchical cluster analysis.2 Five studies2, 9, 19, 21, 27 documented receiving human research ethical approval.

3.4 Operational and contextual information

Seven studies2, 9, 21, 22, 28, 36, 38 provided information pertaining to organisational factors that impact RC operations. For example, infrastructure and resource management. Eight studies2, 9, 19, 21, 22, 27, 28, 37 referred to infrastructure such as buildings, classrooms and other spaces where RC activities took place. Two studies36, 38 did not specify physical facilities.

Two studies22, 28 provided details of course content. Zucchelli and Skinner28 referenced 37 courses split into four categories: (1) understanding mental health difficulties, (2) rebuilding your life, (3) developing knowledge and skill and (4) getting involved. One study38 stated how RC courses were marketed through a course prospectus, one study2 referenced the cost of developing courses equated it to 8000 pounds to develop due to the resource-intense nature of co-production. One study addressed mechanisms for the moderation of subject matter and course construction.22

Three studies2, 21, 28 referenced the development of a peer workforce, senior management endorsement of the presence of lived experience in decision making and the space to build a competent and confident workforce. One study28 provided details on the composition of RC staff. Four studies21, 22, 27, 38 highlighted the importance of educational pedagogy in the RC model. For instance, Ali et al.19 examined the creation of shared learning spaces to facilitate student learning. Similarly, McGregor et al.22 explored the role of co-production and recovery-focused approaches, which provide authentic collaborative learning opportunities.

Four studies2, 9, 21, 28 described the importance of dedicated funding and sufficient resources for successful RC operations. Hayes et al.2 described costs associated with implementing RCs, including those associated with staffing, rent and course development. For example, Participant 3 states: ‘Like a lot of RCs who use co-production, it seems like a lot of the time is free, which is another contentious and difficult issue, people should really be paid for their time. With co-production you do have to the time to do it but also you've got to have the funds to do it properly’. Other operational considerations included the importance of policies and processes,22, 38 administrative support,9 training and development38 and managing organisational cultures.38

Five studies examined funding aspects.2, 21, 36-38 Government departments, particularly mental health departments, were commonly identified as the primary funding source.36, 37 Hayes et al.2 reported three-quarters of the RCs in their study received funding from the NHS. Two studies21, 37 described pilot grants as a means of funding, while Meddings et al.38 detailed funding originating from a partnership between voluntary sector organisations and a Trust. The remaining studies (n = 5)9, 19, 22, 27, 28 did not specify where RC funding originated. Nucelli and Skinner28 highlighted the complex nature of financial sustainability and the challenges associated with securing funding.19 All studies reported a description of RCs (n = 10). Reported definitions are presented in Table 3. Of the 10 studies, nine described their educational institution as a ‘Recovery College’ and one as a ‘Discovery Centre’ (dedicated youth focus).9

| Author | Description |

|---|---|

| Ali et al.19 | ‘The development of RCs can complement existing mental health services, using an educational model to support self-directed recovery and learning opportunities for those experiencing mental ill-health’ (p. 20). |

| Ali et al.27 | ‘[RCs]… stems from both the growing need for mental health service provision to become more recovery oriented, combined with the view that many believe the offer of mainstream services is limited in addressing inequalities and supporting those with long-term conditions.’ ‘People experiencing mental health difficulties, professionals and careers attend as students to a non-prescriptive service where courses are co-designed and co-delivered by people with lived experience and professionals’ (p. 158). |

| Hayes et al.2 | ‘…a relatively new approach to supporting individuals with their mental health’ (p. 1). |

| Hopkins et al.21 | ‘… a new way of working in mental health service provision… The educational rather than medical focus… alongside a genuine commitment to co-production, which values lived experience and professional experience equally, offers a space for individuals, regardless of their background to come together and learn new ways’ (p. 12). |

| Hopkins et al.9 | ‘… operate on recovery principles, utilising an educational model which offers a curriculum developed and delivered in collaboration by mental health professionals, educational professionals, educational professionals and people with lived experience of mental illness’ (p. 188). |

| King and Meddings36 | ‘… educational approach, co-production, co-facilitation and co-learning; recovery-focused and strengths based; progressive; integrated with the community and services with transformational potential and inclusive and open to all. …coproduction and adult learning underpin RCs’ (p. 121). |

| McGregor et al.22 | ‘… the effectiveness of education in relation to supported self-management and expert patient programs specifically in relation to mental health’ (p. 4). |

| Meddings et al.38 | ‘… use an educational approach to enable people to realise their aspirations; take control of their recovery and improve their wellbeing. They combine the strengths of bringing together expertise by lived experience and expertise by professional training. All courses are mental health and recovery relates, co-produced and co-facilitated by peer and professional trainers; and open to people who use services, their relatives, friends and carers and NHS and voluntary sector staff’ (p. 16). |

| Newman-Taylor et al.37 | ‘… one example of coproduced services. Clinicians and service-users adopt an educational model to health care, and work together to develop and run courses that facilitate wellbeing and social inclusion’ (p. 187). |

| Zucchelli and Skinner28 | ‘Shifting the focus from treatment to education… a curriculum of workshops and courses, collaboratively designed and delivered by mental health practitioners and people with lived experience of mental health difficulties’ (p. 183). |

‘My experience has been that they're all completely different. They are idiosyncratic in the way they are set up, in the philosophy and the practicalities and who it is for and how it is done and so on, there's not a clear view’ (P2).

Participant 3 reinforced this perspective noting; ‘RCs can look different and actually they should not be cookie cutters of each other, as they should be co-produced’. Further corroborating this point participant three went on to communicate awareness of RCs was relatively low outside of those that attend or work in them: ‘But I think in terms of the general public knowing about RCs, not really’ (P3).

Six studies9, 19, 28, 36-38 provided reasons to justify the establishment of RCs. These included: a desire for transformative change within mental health services to embrace a more recovery-orientated approach,19, 21, 22 a commitment to addressing the community's specific needs,36 drawing inspiration from existing RCs,36 providing support for individuals facing mental health challenges while tackling healthcare disparities9 and catalysing organisational shifts by influencing attitudes and culture.9, 36

All studies referenced co-production; one provided a specific definition.22 Co-production was framed as the relationship between those with lived experience of mental ill-health and mental health professionals. Five articles9, 27, 28, 37, 38 mentioned that co-production involved people with lived experience working alongside clinicians. Three studies22, 27, 38 mentioned how co-production is applied in practice. For example, Meddings et al.38 described how co-production was embedded within RC operations, from course development to training, governance and evaluation. Table 4 provides author-reported descriptions of co-production.

| Author | Description |

|---|---|

| Ali et al.19 | ‘… co-production throughout the whole college and its culture, enabling an environment where skills and experiences can be exchanged as well as building on existing capabilities’ (p. 2). |

| Ali et al.27 | ‘Co-production in this context should mean those with lived experience are involved in all elements of a recovery college as experts by experience, including curriculum development, delivery and quality assurance’ (p. 20). |

| Hayes et al.2 | ‘Co-production involves people with lived experience working alongside other experts to design and deliver all aspects of the RC’ (p. 2). |

| Hopkins et al.21 | ‘… co-production, which values lived experience and professional experience equally, offers a space for individuals, regardless of their background to come together and learn in new ways’ (p. 12). |

| Hopkins et al.9 | ‘… utilising an educational model which offers a curriculum developed and delivered in collaboration by mental health professionals, educational professionals and people with lived experience of mental illness’ (p. 188). |

| King and Meddings36 | ‘The unique value of coproduction is frequently emphasised’ (p. 121). |

| Meddings et al.38 | ‘Co-production, central to the Recovery College approach, is a form of partnership working and an approach to service development and practice which brings together those who use services and those that provide them’ (p. 17). |

| McGregor et al.22 | ‘Co-production is defined through the New Economics Foundation as: delivering public services in an equal and reciprocal relationship between professionals, people using services, their families and their neighbours. Where activities are co-produced in this way both services and neighbourhoods become far more effective agents of change’ (p. 9). ‘Co-production empathises reciprocal relationships where users of public services, are recognised as active agents with positive capabilities rather than passive beneficiaries’ (p. 9). |

| Newman-Taylor et al.37 | ‘Recovery Colleges are one example of coproduced services. Clinicians and service-users adopt an educational model to health care, and work together to develop and run courses that facilitate wellbeing and social inclusion’ (p. 187). |

| Zucchelli and Skinner28 | ‘It is vital to the ethos of a recovery college that true co-production takes place from the start and is kept at the forefront throughout the college's development and delivery. There may sometimes be a temptation from clinicians to dominate the designing process, pressurised by time constraints, or holding misunderstanding about the true meaning of co-production’ (p. 185). |

The consultation suggested that co-production was a central tenet of RCs, however, participants reported a range of considerations for embedding principles in practice. For example, ‘I think people were trying to run before they could walk’ (P2), suggesting that there may be a tendency to prioritise expediency over thorough co-production efforts, without fully recognising the time and commitment required for co-production. Another participant suggested that co-production was challenging: ‘I think that's something that clinicians really struggle to get their heads around’ (P1). Finally, participants highlighted the relational aspect of co-production and the role of power and expertise when working with those with professional and personal experience. For example, ‘The idea is that you have equal input from people who are experts by training and people who are experts by experience, in all facets’ (P2).

Five studies2, 9, 19, 22, 37 described the concept of recovery. One study19 acknowledged various types of recovery, providing descriptions of personal and clinical recovery. Consistently, broad frames of the individual journey were applied to descriptions of personal recovery. Conversely, the frames surrounding clinical recovery included symptoms, treatment and/or cure. Table 5 presents author-reported descriptions of recovery. Consultation supported findings, highlighting the variations in interpretations of recovery suggesting its temporal nature, the contested language and the juxtaposition between the medical and social aspects of recovery. For example, ‘But like I said, recovery means different things to different people’, (P3) a sentiment echoed by Participant 2: ‘So I'm big in kind of personal recovery or social recovery, in particular as opposed to clinical recovery. So it should be people get out of it what they're looking to get out of it, you know at their particular time of their own journey’.

| Author | Description |

|---|---|

| Ali et al.19 | ‘Clinical recovery encompassing a biomedical view rooted in the belief that mental illness is simply another manifestation of physical illness, a condition in its more serious forms is lifelong, unremitting, degenerative and dependent on medical intervention, usually assessed and judged by “experts” and legitimised by legislation…’ (p. 158). ‘… personal recovery… advocates a shift from managing symptoms to supporting individuals to come to terms with, and overcome challenges associated with living with a mental illness…’ (p. 158). |

| Hayes et al.2 | ‘… involves enabling students to experience key recovery processes of connectedness, hope, identity, empowerment, meaning and purpose and incorporates clinical, societal and personal recovery’ (p. 1). |

| Hopkins et al.9 | ‘… an ongoing, personal journey, experienced and worked towards by the individual with mental illness’ (p. 187). |

| McGregor et al.22 | ‘… may usefully be conceptualised, as a “personal journey of discovery. It involves makings sense of and finding meaning in what has happened; becoming an expert in your own self-care, building a new sense of self and purpose in life; discovering your own resourcefulness and possibilities and using these and the resources available to you to pursue your aspirations and goals” (Perkins et al., 2012, p. 2). This is clearly different from a simple eradication of symptoms’ (p. 4). |

| Newman-Taylor et al.37 | ‘… prioritises self-management and personal recovery outcomes rather than traditional notions of cure from mental-ill health’ (p. 187). |

Seven studies cited a fidelity criterion.2, 9, 19, 22, 28, 36, 38 Perkins et al.12 was cited five times9, 19, 28, 36, 38; Nottingham22 was cited twice22, 38 as was RECOLLECT,2, 23, 36 while three studies21, 27, 37 did not cite a fidelity criteria. Table 6 shows the cited fidelity criteria.

| Reference | Fidelity criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perkins 2012 | Nottingham 2014 | RECOLLECT 2018 | |

| Ali et al.19 | Yes | ||

| Ali et al.27 | |||

| Hayes et al.2 | Yes | ||

| Hopkins et al.9 | Yes | ||

| Hopkins et al.21 | |||

| King and Meddings36 | Yes | Yes | |

| McGregor et al.22 | Yes | ||

| Meddings et al.38 | Yes | Yes | |

| Newman-Taylor et al.37 | |||

| Zucchelli and Skinner28 | Yes | ||

- Note: Perkins Fidelity criteria: Perkins et al.12 proposed eight criteria.6 These were (i) co-production between people with professional and personal experience of mental health problems; (ii) enrolment is open to everyone; (iii) based at a physical location; (iv) reflect recovery principles; (v) operate on an educational learning model; (vi) availability of personal tutors to support student learning; (vii) not a substitute for mainstream educational institutions and (viii) not a replacement for mainstream assessment and treatment services. Nottingham Fidelity criteria: The Nottingham Fidelity Criteria16, 20, 22 proposed seven criteria. These were (i) educational in nature; (ii) collaborative; (iii) strength-based; (iv) personalised; (v) progressive; (vi) engaged with the community and (vii) inclusive. RECOLLECT Fidelity criteria: The Recovery Colleges Characterisation and Testing (RECOLLECT) study2 proposed 12 criteria. These were (i) valuing equality; (ii) learning; tailored to the student; (iii) co-production of RC; (iv) social connectedness; (v) community focus; and (vi) commitment to recovery. The remaining five components are modifiable and include (i) available to all; (ii) location; distinctiveness of course content; (iii) strength-based and (iv) progressive.

For example, one study22 detailed fidelity criteria concerning the operation of RCs, describing how the RC met each criterion in both the results and discussion section. Another study2 reported that most RCs in their sample scored high on fidelity and this was reported in the discussion. However, the consultation indicated that interpretations of fidelity criteria varied based on the local context and were not always suitable as a measure of RC success. As Participant 2 stated: ‘Those measures are a useful starting point to get people to think through these other things that we need. There are things we need to commit to and not beating ourselves up if we don't quite get there’. This participant also expressed in terms of measuring either the impact and/or success of RCs: ‘Fidelity doesn't, doesn't feel right to me’ (P2).

All studies (n = 10) reported study outcomes, from the need for more clarity around terminology19 to working through power imbalances27 and expectations in co-productive working arrangements.9, 38

Three studies2, 36, 37 reported on their limitations, including data collection taking place during COVID-19,2 bias due to reliance on RC managers to self-report2 and lack of generalisability due to small sample sizes.36, 37 More than half of the studies2, 22, 27, 28, 37, 38 provided recommendations for future research endeavours. Recommendations included further evaluations to determine the effectiveness of RCs,2, 37, 38 outcomes22 more in-depth exploration of the fidelity criteria2, 22 and co-production2, 22 as well as operational running costs and commissioning arrangements.2, 28, 37

4 DISCUSSION

This scoping review explored the operationalisation of RCs in HICs and their embodiment of co-production principles. The included papers demonstrated the diverse contexts and sectors that RC operates within. The way RCs are put into operation is influenced by factors such as institutional contexts, positioning, interpretations of key terminology and resource availability. The review identified both commonalities and heterogeneity in RC operational characteristics, along with limited and inconsistent definitions of co-production and recovery.

4.1 Positioning RC operations: Navigating diversity

The RCs in the identified studies were predominantly positioned within the mental health sector, for example, RCs described in the papers by Hopkins et al.21 and Hopkins et al.9 were linked to established mental health services. These findings are consistent with broader literature, where there are few examples of RCs extending their presence beyond the mental health sector. For example, King and Meddings36 report only 10% of RCs are led by educational bodies. RC affiliations with the mental health sector may reflect changes in both national and international policies emphasising recovery-orientated mental health care.2 However, the alignment of the RC model with the medical mental health model remains a source of tension20, 39, 40 as highlighted by Hayes et al.,2 who found that just under half of the RCs were not affiliated with statutory health services.

While some authors have argued for RCs as distinct educational entities located independent of the mental health sector, others have suggested that the medical and the RC educational model should not be seen as binary or oppositional.20, 39, 41 Included studies emphasised the importance of aligning RCs with educational pedagogy21, 22, 27, 38; however, details on the use of educational paradigms, such as transformative learning theories, were lacking. This finding suggests that while there is recognition of the need to integrate pedagogical principles into the design and delivery of RCs programs, there are opportunities for future research on the practical implementation of these educational theories.31

Existing literature suggests that while RCs are framed as learning centres, they should continue to engage with mental health professionals to prevent them from losing relevance within the broader mental health sector.20, 39, 40 However, as evidenced in this review, attracting mental health professional expertise remains challenging9, 42 and specific details on the engagement of mental health professionals remain largely absent from the broader literature.20, 28 These findings collectively emphasise the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the operational identity of RCs. Such exploration is vital not only for addressing the ongoing challenges of engaging mental health professionals but also for enhancing the overall acceptance of RCs within the broader community.

4.2 Definitional and language ambiguity: Shaping perceptions

Definitional ambiguity related to RCs was found to contribute to a lack of clarity regarding their role and value both in the operationalisation of RCs. The included papers presented a diverse range of interpretations (see Table 3). As Collins et al.20 asserts, lost meaning is a real challenge faced by RCs. Similarly, Perkins and Repper40 have suggested that criticisms directed at RCs may stem from a misunderstanding of their mission. Remarkably, none of the included studies presented a consistent definition of co-production or recovery. This lack of consensus is notable, considering the foundational importance of both these concepts as guiding principles12 (see Tables 4 and 5). The consequence of divergent interpretations may not only hinder the development of RCs but may also inadvertently sideline structural factors influencing individuals' access to education, recovery opportunities and the very existence of RCs.37 This raises a significant question: is there a genuine gap in understanding these fundamental concepts, or does it reflect a resistance to the adoption of new approaches within this field? These findings suggest a need for improvements in definitional clarity of terms and the creation of a shared understanding.

RCs are often exemplified by their collaborative nature. Co-production has been widely recognised as the transformative element of the RC model,11, 30, 43 as a process that can challenge established hierarchies.44 The reviewed studies demonstrated consensus that co-production involved service users and providers in designing, delivering, and evaluating RCs. However, evidence of this collaborative process was lacking. None of the studies provided detail on how to establish or maintain co-production, or processes to embed diverse perspectives, or respond to contexts whereby co-production maybe diminished. Moreover, the established lack of understanding of co-production, along with its multiple interpretations,30 may lead to confusion about its true application and value in RCs. This finding highlights an important opportunity for research to address the gap in a consistent understanding and practice of co-production within RCs.18

4.3 Fidelity criteria: Beyond adherence measures

While fidelity criteria were acknowledged across all studies in this review, the lack of application to the operationalisation of RCs was evident. This finding was supported by the stakeholder consultation which suggested a need to shift from rigid fidelity criteria towards exploring and identifying fundamental aspects that underpin the operationalisation of RCs. The broader literature, including Hayes et al.,2 highlights the complexity of RC operations and the challenges in establishing fidelity measurements.45 The lack of consistency in the interpretation and utilisation of fidelity criteria in this review raises questions about the contextual relevance to RC processes, consistent with existing literature,18, 45 which illustrates an evolving field that has given rise to a multitude of diverse evaluation standards. Findings suggest that the term ‘fidelity criteria’ may lack contextual relevance to RC processes and point to the need for a more context-specific approach. For example, criteria such as social connectedness are subjective, driven by values and attitudes,18, 23 making measurement challenging. As suggested by Meddings et al.,46 striking a balance between measuring aspects of RC operations required by funding bodies and commissioners and fostering a culture of service improvement, while staying true to the ethos of RCs and encouraging ongoing innovation23 is essential. However, the lack of clarity about the status of the evidence for the fidelity measures, particularly their relationship to outcomes, remains a concern. Without understanding this relationship, it is difficult to assess the significance of the variation in operationalisation across RCs. Addressing these concerns is crucial for advancing our understanding of fidelity in RCs and ensuring meaningful measurement for all stakeholders involved.

5 STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This review contributes to the limited scholarly landscape on RCs. The 10-year search period across multiple databases, including a range of study designs, provided a broad scope. Along with the consultation stage, which added insights and veracity to findings. Limitations include only studies in English were included, which may have missed contributions and the focus on the academic literature may have led to publication bias. This study did not explore adult education paradigms. Accordingly, future research is recommended in this area.

6 CONCLUSION

This review offers insights concerning the operationalisation of RCs in HICs. The findings emphasise the operational nuances within the RC landscape and the lack of clarity and consensus surrounding key terminologies. This ambiguity poses significant challenges in establishing an optimal operational model for RCs. There is a critical need for further research to inform a more comprehensive understanding of the role of the fidelity criteria and co-production, alongside the processes and structures necessary to operationalise RCs successfully.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KJ, JJ, GC and LM designed the study. KJ was responsible for drafting the protocol paper and coordinating the contributions of all authors to the study protocol. LM, GC and JJ provided input into the background of the study and JJ and GC were responsible for editing and providing guidance on the paper. All authors read and approved the final version.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Jonine Jancey is an Editorial Board member of HPJA and a co-author of this article. To minimise bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication. Open access publishing facilitated by Curtin University, as part of the Wiley - Curtin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee approved this study. HRE2023-0214.

APPENDIX A: TERMINOLOGY AND DEFINITIONS

For this review, the following terms are defined.

Operationalisation: As this review seeks to uncover the practical aspects that underpin the functionality of RCs to gain a deeper comprehension of their operational model, the identification of the tangible elements crucial to daily operations is necessary.47 Operationalisation within the context of public health involves the process of concretely defining and transforming abstract concepts into specific, quantifiable, and observable variables or actions.47 For this review factors such as resource management, roles and responsibility, funding mechanisms, and so forth will be included in generating empirical evidence to shed light on the way RCs work (or fail to work) in reality, to make it possible to consistently and uniformly describe how RCs operate.

Lived experience: Those who have personal experience(s) of a particular issue, such as mental health challenges or alcohol and other drug use, and therefore possess the knowledge of lived expertise.48, 49

Clinician: Also referred to as professional, mental health practitioner or service provider, are individuals actively engaged in the delivery of mental health services within public, private or non-government sectors. This group consists of experts from diverse professional backgrounds and roles within the mental health domain including but not limited to nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, psychiatrists, peer workers.

Recovery: Recovery is ‘being able to create and live a meaningful and contributing life in a community of choice with or without the presence of mental health issues’50 (p. 2).

High-income country: Gross National Income per capita of $13 206 or more (n = 81 countries) as defined by the World Bank 2022.

Fidelity, has been described as the extent to which the delivery of an intervention adheres to a protocol or model originally developed.26, 51

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.