Self-reported behaviour change among multiple sclerosis community members and interested laypeople 6 months following participation in a free online course about multiple sclerosis

Abstract

Issue addressed

Evaluated the impact of the Understanding Multiple Sclerosis (MS) massive open online course, which was intended to increase understanding and awareness about MS, on self-reported health behaviour change 6 months after course completion.

Methods

Observational cohort study evaluating precourse(baseline) and postcourse (immediately postcourse and six-month follow-up) survey data. The main study outcomes were self-reported health behaviour change; change type; and measurable improvement. We also collected participant characteristic data (eg, age, physical activity). We compared participants who reported health behaviour change at follow-up to those who did not and compared those who improved to those who did not using χ2 and t tests. Participant characteristics, change types and change improvement were described descriptively. Consistency between changes reported immediately postcourse and at the 6-month follow-up was assessed using χ2 tests and textual analysis.

Results

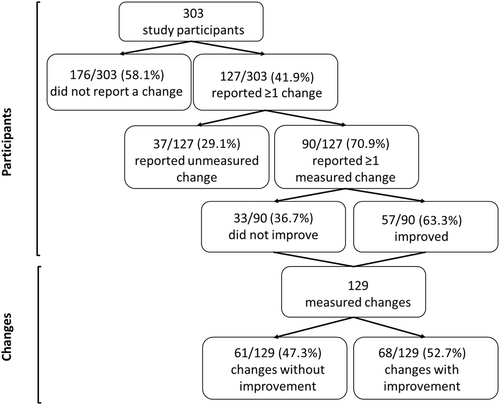

N = 303 course completers were included in this study. The study cohort included MS community members (eg, people with MS, healthcare providers) and nonmembers. N = 127 (41.9%) reported behaviour change in ≥1 area at follow-up. Of these, 90 (70.9%) reported a measured change, and of these, 57 (63.3%) showed improvement. The most reported change types were knowledge, exercise/physical activity and diet. N = 81 (63.8% of those reporting a change) reported a change in both immediately and 6 months after course completion, with 72.0% of those that described both changes giving similar responses each time.

Conclusion

Understanding MS encourages health behaviour change among course completers up to 6 months after course completion.

So what?

An online education intervention can effectively encourage health behaviour change over a 6-month follow-up period, suggesting a transition from acute change to maintenance. The primary mechanisms underpinning this effect are information provision, including both scientific evidence and lived experience, and goal-setting activities and discussions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Health education is one of the primary tools of health promotion. As such, health education interventions often aim to both increase knowledge and encourage health behaviour change.1, 2 In the Internet era, health educational interventions are increasingly being made available online. For example, the leading aggregator of massive open online courses (MOOCs) currently lists more than 1900 health and medicine MOOCs.3 However, the impact of online health education interventions is not well understood.4, 5 Although there is good evidence that online health education interventions increase related knowledge, there is insufficient evidence with respect to their effect on other health behaviours and outcomes (eg, health literacy) to reach a conclusion.4, 5 Even less is known about the long-term effects of these interventions, with few studies conducting follow-up assessments.4, 5

Here, we explore the impact of an online health education intervention, the Understanding Multiple Sclerosis (MS) MOOC, on self-reported health behaviour change. The Understanding MS MOOC is a freely available six-week online course that presents information on the underlying pathology, symptoms, risk factors and disease management of MS, as well as its impact on everyday life.6 The course is aimed at the MS community (eg, people living with MS, carers and supporters, and healthcare and service providers) and interested laypeople, and incorporates both lived experience and clinical/academic content throughout the course. To date, the course has completed six enrolments, with >28 000 people from >130 countries enrolled. The course is primarily a health promotion and health education intervention, defined by Michie et al.7 as “focusing on imparting knowledge and developing understanding.”7

Previously, we have shown that the Understanding MS MOOC encourages health behaviour change immediately following course completion, with 44.1% of study participants reporting a change.4, 5 We found that the most common types of behaviour change were exercise or physical activity, diet and knowledge, including understanding and awareness. Further, among those who reported a change type that was measured in the study surveys, 68.1% showed improvement.4, 5 We also found that participants who reported a change had significantly lower precourse quality of life and diet quality than those who did not. Among people with MS, those who reported a change also had significantly lower precourse self-efficacy and greater symptom severity. Similarly, we found that participants who improved had significantly lower precourse MS knowledge and health literacy than those who did not.4, 5

However, the effect of the course on health behaviour change and change maintenance over longer time periods remains unclear. In this study, we expand our analysis to assess the impact of the course 6 months after course completion. We evaluate the development of change maintenance, using guidance from the work of Lally et al.8 which found that, on average, automaticity or maintenance occurred 66 days postchange.

- What is the impact of Understanding MS MOOC on self-reported health behaviour change 6 months after course completion?

- What types of behaviour change do participants report 6 months after course completion?

- Do participants who report a behaviour change improve in the reported change area?

- Are there differences in characteristics or baseline health factors (eg, health literacy) between those who reported a change or improved and those who did not?

- How consistent are participants who self-reported health behaviour change in both the postcourse and 6 month follow-up surveys?

2 METHODS

The methods of this study have been described in detail in a previous publication4, 5. We summarised the methods briefly below. This study was approved by the University of Tasmania Social Science Human Research Ethics Committee (H0017924; H0018314; S0020031). All participants gave informed consent prior to taking part.

2.1 Design

We recruited Understanding MS MOOC enrolees who indicated that they were interested in taking part in course-related research at registration. Participants were asked to complete three largely identical online questionnaires: one prior to the course content becoming available (precourse survey) and one immediately after course completion 8–10 weeks later (postcourse survey), and one 6 months after course completion (follow-up survey). Participants were given 1-2 weeks to complete each questionnaire.

A previous publication evaluated the postcourse survey data4, 5. Here, we extend the analysis to evaluate follow-up survey data.

2.2 Sample

Inclusion criteria for this study were: (i) enrolment in one of the first three iterations of the Understanding MS MOOC (April 2019; September 2019; March 2020); (ii) self-reported course completion on the postcourse survey; and (iii) completion of at least one assessment tool on all three surveys.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Participant characteristics

The study questionnaire collected participant characteristic data, including self-reported MS community roles (eg, person with MS, caregiver, healthcare provider). Participant relationship status and education level were categorised into binary variables: partnered (married or de facto partnership) or not partnered, and university degree (university undergraduate or postgraduate degree) or no university degree.

Participants were able to select multiple MS community roles from the following list: person with MS, caregiver (formal or informal carer), specialist healthcare provider (neurologist, MS nurse or general practitioner), generalist healthcare provider (non-MS nurse, allied healthcare provider), service provider, researcher and none (did not identify as a member of the MS community). However, >80% only chose one. Among those who selected >1, we assigned a primary MS community role for our analysis. Primary roles were assigned in descending order following the list provided above. Therefore, a person with MS was categorised as a person with MS regardless of what other roles they might hold (eg, service provider). Similarly, among people not living with MS, caregivers were assigned the role caregiver even if they held other roles. This information was also used to assign participant MS status (living with MS/not living with MS).

2.3.2 Outcome measures

Have you changed anything about your approach to healthcare, your lifestyle, or disease management after enrolling in the understanding MS online course?

Those that responded “yes” were given the option of describing the change(s) they had made in a free text response. A single author (SC) then categorised the reported changes into types of behaviour change and assessed behaviour change types to determine if they were quantified in the questionnaire (see Table 1). Textual analysis was not required, as participants provided concise and straight-forward descriptions of the changes they made. For example, the statement “I am now doing more exercise and watching what I eat more also spending more time relaxing with family” contained three change types: exercise/physical activity; diet; and stress management. Of those, exercise/physical activity and diet were categorised as measured change because both physical activity and diet quality were assessed in the precourse and postcourse surveys.

| Outcome | Definition | Outcome measures | Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS Knowledge | Knowledge about MS pathology, symptoms, risk factors and disease management | MS Knowledge Assessment Scale9 | 0-22 | Higher scores indicate greater knowledge |

| Health literacy | The ability to obtain, process, and understand health information and services necessary to make appropriate health decisions10 | Health Literacy Questionnairea, subscale 1–511 | 1-4 | Higher scores indicate greater health literacy |

| Health Literacy Questionnairea, subscale 6-911 | 1-5 | |||

| Resilience | The ability to bounce back or rise above and overcome adversity12 | Brief Resilience Scale13 | 1-5 | Higher scores indicate greater resilience |

| Quality of life (health related) | “the health aspect of quality of life that focuses on people's level of ability, daily functioning and ability to experience a fulfilling life” (ISOQOL) | Personal Wellbeing Index14 | 0-10 | Higher scores indicate greater quality of life |

| Self-efficacy | The perceived capability to perform a target behaviour15 | General Self-Efficacy Scaleb,16 | 10-40 | Higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy |

| Self-efficacy for Managing Chronic Diseasec,17 | 1-10 | Higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy | ||

| MS symptom severity | MSSymSb18 | 0-10 | Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity | |

| Diet quality | Self-reported | 0-10 | Higher scores indicate better diet quality | |

| Physical activity | International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)19—Short Form | Continuous | Higher scores indicate greater physical activity | |

| Weight | Self-reported (kg) | Continuous | ||

| Vitamin D supplementation status | Self-reported | Y/N | ||

| Smoking status | Smoking status Average number of cigarettes or equivalent per day | Self-reported | Y/N Continuous | |

| Alcohol intake | Average number of days/week drinking Average number of drinks/drinking day | Self-reported | 0-7 0 to >6 | |

| Sun exposure | Weekend exposure Weekday exposure Holiday exposure | Self-reported | <1 h/day to >4 h/day |

- a The Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) is comprised of 9 subscales measuring different aspects of health literacy. The subscale scores cannot be aggregated. The subscales are as follows: (i) feeling understood and supported by healthcare providers; (ii) having sufficient information to manage health; (iii) actively managing health; (iv) social support for health; (v) appraisal of health information; (vi) ability to actively engage with healthcare providers; (vii) Navigating the healthcare system; (viii) ability to find good health information; (ix) understand health information well enough to know what to do.

- b Only assessed in people not living with MS.

- c Only assessed in people living with MS.

Measured changes were evaluated using pre/post comparisons (precourse score—follow-up score, where possible) to determine if an improvement (change in score >0, change in weight of <0, or change in status) was observed. Precomparisons/postcomparisons were then categorised as a binary variable: improved or not improved.

2.3.3 Other measures

The study surveys measured an array of health-related factors and behaviours. The tools used are presented in Table 1.

2.4 Analysis

The representativeness of the study sample compared to the precourse sample has been evaluated elsewhere.20 These comparisons were made using χ2 and t tests.

Participant characteristics, change types and change improvement were described descriptively using means, standard deviations, frequencies and percentages. We assessed the frequency of different change types in MS community role subgroups with N > 5 and compared between groups.

We compared participants who reported a behaviour change in the follow-up survey to those who did not; and, among those who reported a measured change, we compared those who improved to those who did not based on participant characteristics and baseline scores from the precourse assessment. In both cases, we used χ2 and t tests.

We determined the consistency of participant self-reported change by comparing participant responses to the yes/no question presented above on the postcourse and follow-up surveys using a χ2 test. Among participants who reported making a change in both the postcourse and follow-up surveys, we qualitatively compared the change(s) using textual analysis. A single author (SC) read through all of the free text descriptions and assigned the change(s) as similar or dissimilar. Examples of similar responses are presented in the text below.

All analyses were conducted in STATA 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

3 RESULTS

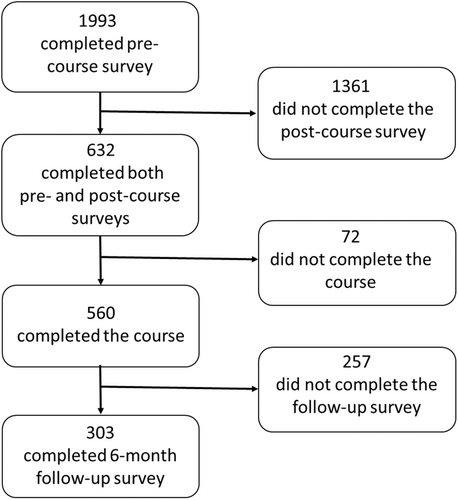

Figure 1 depicts the flow of participants into this study. Of the 1993 people who completed at least one instrument on the precourse (baseline) survey, 303 (15.2%) participants self-reported completing the course and completed at least one instrument on the precourse, postcourse and follow-up surveys.

3.1 Representativeness

As stated above, the representativeness of the study sample compared to the precourse sample has been evaluated elsewhere.20 Briefly, there were no statistically significant differences in sex, relationship status, education level, disease or baseline MS knowledge, resilience, self-efficacy, or in the severity of 10 of the 11 MS symptoms assessed. The study sample was older on average (53.4 vs 46.8 years; P < .001) and included a higher percentage of people living with MS (45.9% vs 38.7%; P = .006) than the precourse sample, and had higher baseline health literacy and quality of life. However, the differences in health literacy and quality of life were small, ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 units on scales of 4-5 and 10, respectively. People with MS in the study sample also had significantly lower baseline fatigue severity (5.7 vs 6.2 out of 10; P = .041) than the precourse sample.

3.2 Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 2. Most participants were female (83.4%), partnered (68.7%), and had a university degree (54.5%). Nearly half (45.9%) were people living with MS, and nearly one quarter (22.4%) were caregivers. The cohort had a mean age of 53.3 years and among people with MS, a mean disease duration of 8.1 years from diagnosis.

| All (N = 303) | Reported change (N = 127) | Reported no change (N = 176) | Improveda (N = 57) | Did not improve (N = 33) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 | P-value | N | % | N | % | χ2 | P-value | |

| Sex | 0.128 | .721 | 0.054 | .817 | ||||||||||

| Female | 252 | 83.4 | 104 | 82.5 | 148 | 84.1 | 51 | 89.5 | 29 | 87.9 | ||||

| Male | 50 | 16.6 | 22 | 17.5 | 28 | 15.9 | 6 | 10.5 | 4 | 12.1 | ||||

| Relationship status | 0.584 | .300 | 1.187 | .276 | ||||||||||

| Partnered | 208 | 68.7 | 85 | 66.9 | 123 | 69.9 | 35 | 61.4 | 24 | 72.7 | ||||

| Not partnered | 95 | 31.4 | 42 | 33.1 | 53 | 30.1 | 22 | 38.6 | 9 | 27.3 | ||||

| Education level | 0.46 | .545 | 0.031 | .861 | ||||||||||

| University degree | 165 | 54.5 | 66 | 52.0 | 99 | 56.3 | 27 | 47.4 | 15 | 45.5 | ||||

| No university degree | 138 | 45.5 | 61 | 48.0 | 77 | 43.7 | 30 | 52.6 | 18 | 54.5 | ||||

| MS community role | 3.017 | .807 | 3.227 | .780 | ||||||||||

| PwMS | 139 | 45.9 | 56 | 44.1 | 83 | 47.2 | 22 | 38.6 | 16 | 48.5 | ||||

| Caregiver | 68 | 22.4 | 29 | 22.8 | 39 | 22.2 | 13 | 22.8 | 9 | 27.3 | ||||

| Specialist HCP | 8 | 2.6 | 3 | 2.4 | 5 | 2.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Generalist HCP | 39 | 12.9 | 16 | 12.6 | 23 | 13.1 | 7 | 12.3 | 4 | 12.1 | ||||

| Service provider | 7 | 2.3 | 2 | 1.6 | 5 | 2.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Researcher | 4 | 1.3 | 3 | 2.4 | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 3.5 | 1 | 3.0 | ||||

| None | 38 | 12.5 | 18 | 14.2 | 20 | 11.4 | 11 | 19.3 | 3 | 9.1 | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | P-value | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.3 | 11.5 | 50.6 | 12.1 | 55.2 | 10.7 | 3.515 | < .001 | 51.9 | 12.2 | 48.1 | 11.2 | −1.473 | .144 |

| Disease duration from year of first symptomb | 13 | 10.4 | 13.9 | 11.2 | 12.4 | 9.7 | −0.855 | .394 | 15.9 | 12.2 | 11.6 | 9.7 | −1.167 | .251 |

| Disease duration from year of diagnosisb | 8.4 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 7.3 | 0.643 | .521 | 10.3 | 10 | 5.1 | 4.7 | −1.953 | .059 |

- Abbreviations: HCP, healthcare provider; PwMS, person with MS.

- a Number of people who improved in ≥1 measured change.

- b Among people living with MS.

Table 3 presents the baseline health-related factor and behaviour assessment scores for the study cohort. Participants had moderate to high mean MS knowledge, resilience, health literacy, quality of life and self-efficacy scores. Participants living with MS reported mild to moderate symptom severity.

| All (N = 303) | Reported change (N = 127) | Reported no change (N = 176) | t | P-value | Improved (N = 57) | Did not improve (N = 33) | t | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS knowledge (MSKAS) | 15.9 (4.4) | 15.6 (4.6) | 16.1 (4.3) | 0.891 | .374 | 14.6 (4.7) | 16.4 (4.4) | 1.755 | .083 |

| Resilience (BRS) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.8) | −1.780 | .076 | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.8) | 1.196 | .235 |

| Health literacy (HLQ) | |||||||||

| HLQ subscale 1 | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.5) | −0.316 | .752 | 3.1 (0.6) | 3.2 (0.4) | 0.766 | .446 |

| HLQ subscale 2 | 3.0 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.5) | −0.662 | .509 | 3.0 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.5) | −0.338 | .736 |

| HLQ subscale 3 | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.5) | −0.422 | .674 | 3.0 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.4) | 0.189 | .851 |

| HLQ subscale 4 | 2.9 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.5) | −1.269 | .205 | 2.9 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.6) | 0.925 | .358 |

| HLQ subscale 5 | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.5) | −1.327 | .186 | 3.1 90.4) | 3.2 (0.5) | 0.928 | .356 |

| HLQ subscale 6 | 3.9 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.7) | 0.972 | .332 | 3.8 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.50 | 0.76 | .449 |

| HLQ subscale 7 | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.6) | 0.446 | .656 | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.5) | 0.363 | .718 |

| HLQ subscale 8 | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.6) | 0.508 | .612 | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.5) | −0.003 | .998 |

| HLQ subscale 9 | 4.1 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.6) | −0.095 | .925 | 4.1 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.5) | −0.008 | .994 |

| Quality of life (PWI) | 6.9 (1.8) | 6.7 (1.8) | 7.0 (1.8) | 1.029 | .304 | 6.7 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.7) | 0.342 | .734 |

| Self-efficacy | |||||||||

| GSEa | 31.4 (3.6) | 31.9 (3.6) | 31.0 (3.9) | −1.547 | .124 | 31.7 (3.9) | 32.8 (3.9) | 0.945 | .350 |

| SEMCDb | 5.9 (2.1) | 6.0 (2.0) | 5.8 (2.3) | −0.512 | .61 | 5.9 (2.2) | 6.0 (1.7) | 0.201 | .842 |

| MS symptom severityb | |||||||||

| Fatigue | 5.7 (2.7) | 5.3 (2.7) | 6.0 (2.7) | 1.584 | .116 | 5.4 (2.6) | 4.9 (2.4) | −0.647 | .522 |

| Walking difficulties | 5.0 (3.1) | 4.9 (2.8) | 5.1 (3.3) | 0.488 | .627 | 5.0 (3.0) | 4.6 (2.7) | −0.417 | .679 |

| Difficulty with balance | 5.1 (3.0) | 5.4 (2.7) | 4.9 (3.2) | −0.994 | .322 | 6.0 (2.7) | 4.7 (2.7) | −1.514 | .139 |

| Cognitive symptoms | 4.4 (2.8) | 4.5 (2.8) | 4.4 (2.8) | −0.200 | .842 | 3.8 (2.8) | 5.3 (2.4) | 1.781 | .083 |

| Pain | 4.0 (3.1) | 3.8 (2.9) | 4.2 (3.3) | 0.717 | .475 | 4.0 (3.1) | 3.5 (2.4) | −0.584 | .563 |

| Vision problems | 2.6 (2.7) | 2.8 (2.5) | 2.5 (2.8) | −0.669 | .505 | 2.6 (2.5) | 3.4 (2.3) | 1.017 | .316 |

| Bladder problems | 4.6 (3.1) | 5.0 (2.9) | 4.2 (3.3) | −1.447 | .15 | 5.2 (3.2) | 4.9 (2.9) | −0.239 | .812 |

| Bowel problems | 3.5 (3.1) | 3.8 (3.0) | 3.3 (3.2) | −0.859 | .392 | 4.0 (3.1) | 4.1 (2.9) | 0.12 | .913 |

| Sexual dysfunction | 4.0 (3.7) | 3.9 (3.3) | 4.1 (4.0) | 0.397 | .692 | 3.7 (3.0) | 3.3 (3.0) | −0.377 | .709 |

| Depression | 4.0 (3.0) | 4.2 (2.8) | 3.9 (3.2) | −0.477 | .634 | 4.7 (2.3) | 3.8 (2.80 | −1.100 | .279 |

| Anxiety | 3.9 (3.1) | 4.1 (3.0) | 3.7 (3.1) | −0.837 | .404 | 4.5 (3.0) | 3.8 (2.6) | −0.798 | .430 |

| Sensory symptoms | 5.6 (3.1) | 5.7 (3.0) | 5.6 (3.2) | −0.161 | .872 | 5.9 (3.2) | 5.5 (2.8) | −0.415 | .681 |

| Spasticity | 4.5 (3.3) | 4.4 (3.3) | 4.6 (3.3) | 0.338 | .736 | 4.4 (3.5) | 4.4 (3.0) | 0.068 | .946 |

| Diet quality | 7.1 (1.7) | 6.9 (1.8) | 7.3 (1.6) | 1.779 | .076 | 6.4 (2.0) | 7.2 (1.3) | 2.059 | .043 |

| Physical activity | 2258.8 (2147.7) | 2272.0 (1907.7) | 2248.9 (2319.2) | −0.090 | .929 | 2153.2 (1886.7) | 2565.6 (2023.5) | 0.962 | .339 |

- a Only assessed in people not living with MS.

- b Only assessed in people living with MS.

3.3 Assessing self-reported behaviour change

One hundred and twenty-seven participants (41.9%) reported making a change following completion of the Understanding MS MOOC (Table 2 and Figure 2). The participants who reported making a change were similar to those who did not (Table 3). There were no differences between the two groups in sex, education level, relationship status, disease duration or baseline health-related factor or behaviour scores (Table 2 and Table 3). However, participants who reported making a change were on average about 5 years younger than those who did not (50.6 vs 55.2 years, P < .001).

Table 4 presents the reported behaviour change types. In the total sample, the most common change types were exercise or physical activity, diet and knowledge. Nearly one-third of participants who reported a change reported increasing their activity level (32.2%) or improving their diet (29.9%), and more than one quarter (26.8%) reported greater knowledge, understanding or awareness. None of the participants reported a regression in a change type; where a direction of change was described, all changes were reported as improvements. There were four MS community role subgroups with sample sizes >5: people with MS, caregivers, generalist healthcare providers, and nones (do not identify as a member of the MS community). There were substantial differences these subgroups. More than 20% (25.0-51.7%) of caregivers, generalist HCPs and nones reported changes in knowledge. However, only 10.7% of people with MS reported a similar change. Conversely, people with MS, generalist HCPs and nones commonly reported dietary changes (25.0-39.3%), while only 17.2% of caregivers reported a similar change.

| Change typea | All (N = 127) | PwMS (N = 56) | Carer (N = 29) | Generalist (N = 16) | None (N = 18) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Exercise or physical activity | 41 | 32.3 | 26 | 46.4 | 5 | 17.2 | 7 | 43.8 | 3 | 16.7 |

| Diet | 38 | 29.9 | 22 | 39.3 | 5 | 17.2 | 4 | 25.0 | 5 | 27.8 |

| Knowledgeb | 34 | 26.8 | 6 | 10.7 | 15 | 51.7 | 4 | 25.0 | 6 | 33.3 |

| Care or support practice | 21 | 16.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 31.0 | 7 | 43.8 | 2 | 11.1 |

| Disease or health managementc | 17 | 13.4 | 14 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 12.5 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Empathy or compassion | 11 | 8.7 | 2 | 3.6 | 5 | 17.2 | 1 | 6.3 | 2 | 11.1 |

| Healthy lifestyle or living | 8 | 6.3 | 2 | 3.6 | 3 | 10.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Stress management | 8 | 6.3 | 6 | 10.7 | 1 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Weight loss | 8 | 6.3 | 5 | 8.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 16.7 |

| Communication around MS | 7 | 5.5 | 2 | 3.6 | 1 | 3.4 | 2 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Disease or health monitoring | 6 | 4.7 | 5 | 8.9 | 1 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Accessing or evaluating health information | 5 | 3.9 | 4 | 7.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Self-care | 5 | 3.9 | 5 | 8.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Mindfulness or cognitive exercises | 4 | 3.1 | 4 | 7.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Share knowledge | 4 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 10.3 | 1 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Vitamin supplementation | 4 | 3.1 | 2 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Drinking habits | 3 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Sun exposure | 3 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Not described or unclear | 3 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 11.1 |

| Attitude | 2 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Confidence or empowerment | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.4 | 1 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Reached out for support | 2 | 1.6 | 2 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sleep | 2 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Cholesterol | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| COVID mentioned | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Engagement in research | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Mental health | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Relocation | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Resilience | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Smoking | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Social interaction | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Workplace issues | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total number of reported changes | 247 | 119 | 52 | 32 | 29 | |||||

- a Sorted by percentage for all participants.

- b Includes awareness, understanding and knowledge.

- c Includes symptom management.

Nearly half of people with MS and generalist HCPs reported changes in exercise or physical activity (46.4% and 43.8%, respectively), but caregivers and nones did not commonly report similar changes. Changes in disease or health management were only commonly reported by people with MS (25%), and changes in care and support practice were only commonly reported by caregivers (31.0%) and generalist HCPs (43.8%).

3.4 Consistency in reported change(s)

Of the 303 study participants, 120 (39.6%) reported making a change in the postcourse survey and 127 (41.9) reported making a change in the follow-up survey. There were significant differences in participant responses between the surveys (χ2 = 53.42; P < .001); 81 participants (26.7%) reported making a change in both the postcourse and follow-up surveys and 137 (45.2%) reported making no changes in both surveys.

-

- Post-course

-

- I am more aware of my healthcare and have made a determined effort to maintain my positives regarding my lifestyle

-

- Follow-up

-

- i am more aware of my own health and the health of friends with any medical concerns

-

- Post-course

-

- more walking, less chocolate

-

- Follow-up

-

- move more, eat less chocolate.

-

- Post-course

-

- I am now doing more exercise and watching what I eat more also spending more time relaxing with family.

-

- Follow-up

-

- I have been looking more at what I eat and making some changes also I have been doing some more exercise and taking some time out for me to just relax.

3.5 Assessing improvement in self-reported behaviour change

Of the 127 participants, who reported making a change, 90 (70.9%) reported a change in at least one measured change type (Figure 2). Of these, 57 (63.3%) improved in at least one change type (Figure 2). Participants who improved were similar to those who did not based on the factors we assessed. There were no differences between the groups in any participant characteristic or baseline health-related factor or behaviour except diet quality (Table 2 and Table 3). Participants who improved had a lower mean baseline diet quality rating than those who did not (6.4 vs 7.2, P = 0.043).

Eight reported change types were measured in the precourse, postcourse and follow-up assessments, with 129 total measured changes reported. Of these, 68 (52.7%) measured changes were improved (Figure 2). Table 5 presents the percentage of participants reporting a change in a given change type that improved. Four change types had sample sizes >5 (range: 8-40): diet, exercise or physical activity, knowledge and weight loss. Of these, the change type with the greatest likelihood of improvement was knowledge (79.4%), followed by weight loss (62.5%), exercise (57.5%) and diet (27.0%).

| Change type | Reported improvementa | N improved | % improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | 37 | 10 | 27.0 |

| Drinking habits | 3 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Exercise | 40 | 23 | 57.5 |

| Knowledgeb | 34 | 27 | 79.4 |

| Resilience | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sun exposure | 2 | 1 | 50.0 |

| Vitamin D supplementation | 4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Weight loss | 8 | 5 | 62.5 |

| Total number of improvements | 129 | 68 |

- a Participants were able to demonstrate improvement in ≥1 change area.

- b Includes awareness, understanding and knowledge.

Four change types had very small samples (≤5; range:1-4): drinking habits, resilience, sun exposure and vitamin D supplementation. Of these, two (vitamin D supplementation and resilience) had 0% improvement, meaning none of the participants who reported a change demonstrated improvement in the assessments.

4 DISCUSSION

Six months following the completion of the Understanding MS MOOC, 41.9% of the study cohort reported a health behaviour change. The most commonly reported change types were knowledge (including understanding and awareness), exercise or physical activity and diet. Among those reporting a change, nearly two-thirds (63.8%) had also reported a change on the postcourse survey. Of those who described the changes they made, 72.0% reported making similar changes, suggesting a transition from change to maintenance. Among those reporting a change, there was also a substantial likelihood of improvement. Of the 90 participants that reported a measured change, nearly two-thirds (63.3%) improved in at least one change type.

A similar percentage of the study cohort reported making a change on the postcourse survey as did on the follow-up survey (44%-45%21). Further, the most commonly reported change types were the same between the two surveys.21 This suggests that the course had a consistent effect on participants and that its impact is sustainable up to 6 months following completion. These are several theoretical explanations for this result. It may reflect the course's effect on habit formation, motives, psychological resources, or social influences.22 The course may encourage habit formation through goal-setting activities, may offer new motivation or psychological resources through information provision and may change social influence through discussion boards with peers.

Of the 127 participants who reported a change in the six-month follow-up survey, 81 (63.8%) also reported a change in the postcourse survey. Among those who described the changes, nearly three-quarters (72.0%) reported making similar changes. Again, this suggests that course participation may encourage sustained behaviour change, or a transition from behaviour change to long-term maintenance. Interestingly, more than one-third (36.2%) of participants who reported a change at follow-up did not report a change in the postcourse survey. This suggests that for some participants, the postcourse assessment, which occurs immediately after the course closes, may happen too soon to capture resulting behaviour change.

Among participants who reported a measured change type, there was a substantial likelihood of improvement. This agrees with our findings from the postcourse survey.21 Further, we found some strikingly similar results with respect to the percentage of participants who improved in a given change type. Among those who reported a change in exercise or physical activity, 51.6% improved on the postcourse survey and 57.5% improved on the follow-up survey. Similarly, of those who reported a change in knowledge, 78.9% improved on the postcourse survey and 79.4% improved on the follow-up survey. However, there were also some noticeable differences, with 0% of those reporting changes to drinking habits showing improvement in the postcourse survey and 66.7% improving on the follow-up survey. Conversely, 75% of those who reported an increase in vitamin D supplementation showed improvement on the postcourse survey, while 0% did on the follow-up survey. This may reflect the small sample sizes for these change types, the seasonality of changes to vitamin D supplementation (ie, people are more likely to supplement in winter months) or the time required to make a quantifiable change.

Unlike our previous study, among this cohort, there were no significant differences in baseline health factors and behaviours (ie, the behaviours and factors listed in Table 1) between those who reported a change and those who did not, or between those who improved and those who did not. This suggests that the course is equally effective in encouraging behaviour change across the study cohort. This is a notable break from past work finding that lower self-efficacy and motivation are associated with a lower likelihood of diet and physical activity-related behaviour changes.23 However, it is worth noting that the difference in these results may be driven by the relatively high baseline health behaviour and factor scores in this cohort, which may suggest that they are not generalisable. It is important to note that one of the most commonly reported behaviour change types, knowledge, is more likely a mechanism of action in that it likely aids other behaviour change and may assist the transition from behaviour change to maintenance.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study are its large and diverse cohort, and its six-month follow-up assessment. The main limitation of this study is its vulnerability to selection bias; only 15.2% of the initial cohort completed the course and completed at least one assessment tool on all three study surveys. However, this still exceeds the threshold 10% response rate recommended by the Centre for Higher Education Quality for viability.24 Further, despite attrition, the study cohort was similar to the initial cohort based on sex, relationship status, education level, disease duration, and baseline MS knowledge, resilience, self-efficacy, and symptom severity.

5 CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that an online health education intervention can encourage health behaviour change up to 6 months after completion. Further, it shows that the resulting change is often consistent across the follow-up period, suggesting that participants transition from behaviour change towards maintenance. This has implications for future behavioural change interventions within the MS community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the study participants, who generously gave their time to take part in this research.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Multiple Sclerosis Ltd (Australia) has provided funding for the maintenance and administration of the Understanding MS MOOC through December 2022.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the University of Tasmania Social Science Human Research Ethics Committee.

PARTICIPANT CONSENT

All participants gave informed consent prior to taking part.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.