Health promotion programs for middle-aged adults that promote physical activity or healthy eating and involve local governments and health services: A rapid review

Abstract

Background

Noncommunicable diseases can be prevented or delayed through health promotion programs. Little is known about programs delivered by partnership organisations that address lifestyle behaviours. The study's purpose was to review the literature on physical activity or healthy eating health promotion programs, delivered in partnership by the local government and local health services, to describe characteristics of programs and their impact on physical activity, healthy eating or related health outcomes among middle-aged adults.

Methods

This rapid review was conducted from November 2021 to June 2022, informed by the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods guidance for conducting rapid reviews. Articles published in English since 2000 were identified in Medline, Embase, CINAHL, AgeLine and Scopus databases. A narrative synthesis was performed.

Results

Ten articles involving 19 802 participants were identified from a total of 4847 articles identified from the search. The primary role of the partnership was providing funds. Other roles were facilitating stakeholder involvement, program development, delivery and recruitment. Positive outcomes were likely if programs were developed by collaborative stakeholder partnerships, informed by previous research or a behaviour change framework. The heterogeneity of study designs and reported outcomes did not permit meta-analysis.

Conclusion

This review highlights the lack of evidence of local government-health service partnerships delivering physical activity or healthy eating health promotion programs for middle-aged adults. Programs designed collaboratively with an evidence base or a theory base are recommended and can guide future work investigating strategies for partnership development.

So What?

Physical activity or healthy eating health promotion programs need early stakeholder collaborative input designed with a theory/evidence base. This can guide future work for investigating strategies for partnership development.

1 BACKGROUND

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are a major global public health problem, responsible for almost 70% of all global deaths.1 Yet, the risk of developing NCDs can be ameliorated by the adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviours such as physical activity and healthy eating.1 There is clear guidance on recommended physical activity and nutrition for health benefits2, 3 and evidence that commencing healthy behaviours in the middle-aged years is associated with longevity benefits and delays physical disability in older years.4, 5 However, in 2017 to 2018 just over 1 in 2 Australian adults (55%) were not participating in sufficient physical activity.6

Adults in their middle-aged years may face challenges in adopting healthy behaviours. Alongside employment responsibilities, 37% of adults aged 45+ juggle carer responsibilities7 and 60% have chronic health conditions.8 Targeted health promotion programs for middle-aged adults are warranted particularly with an ageing population.9

The 1997 World Health Organization Jakarta Declaration stated that health promotion requires a partnership between sectors at all levels of governance and society for health and social development. Health promotion is a joint responsibility but also offers partners mutual benefits. Through the sharing of expertise, skills and resources,10 and enabling wide ownership of health,11 health promotion partnerships can reduce inequities that could be due to individual, social or environmental determinants.12

In the community, health promotion programs have traditionally been delivered by local primary health care services.13 Yet, local governments play a crucial role in providing communities with safe and healthy environments and are ideally placed to deliver health promotion programs. A partnership between the local health service and local government could therefore be an efficient and effective way to promote healthy lifestyles among middle-aged adults.

- What were the physical activity and healthy eating health promotion programs for adults aged 45+, delivered in partnership between local government and local health service documented in the peer-review literature?

- Of the identified programs, what were the roles and nature of the partnership?

- Of the identified programs, what type and format of health promotion programs were conducted?

-

Of the identified programs, what was the likely impact on:

- physical activity,

- nutrition, and

- related health conditions, including diabetes, obesity and mental health.

2 METHODS

This review was informed by the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods guidance15 and was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews items (PRISMA-ScR).16 The review protocol was preregistered on Open Science Framework, on November 18, 2021 and can be accessed at https://osf.io/fchak.

A comprehensive selection of relevant single-subjects and multidisciplinary databases were searched, consisting of Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), AgeLine (EBSCO) and Scopus. The search strategy was developed using the PICo framework17: adults 45+ years (Population), healthy eating or physical activity promotion (Intervention) and local government (Context).

The search strategy was collaboratively developed between the librarian and the research team (Appendix). Human, English language and publication date (2000-current) search limits were applied. All database searches were performed on November 17, 2021. Two reviewers each screened the titles and abstracts of all records obtained from the search according to study criteria and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus. The full text of potentially relevant records was each screened by two reviewers for eligibility and discrepancies resolved by discussion and consensus or third reviewer.

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Full-text quantitative studies testing an intervention either at a population or individual level and published in peer-reviewed journals were included. According to the purpose of the review, studies were included if (i) the setting was comparable to Australia, that is, high-income countries with a local government and health service structure, (ii) the intervention was provided in partnership between a local government and local health service, (iii) the intervention involved a health promotion program and targeted at least physical activity or nutrition as one of the health behaviours, (iv) the target population was middle-aged community-dwelling adults, and (v) the outcome was physical activity, healthy eating or clinical health condition related to diabetes, obesity or mental health.

Grey literature, books, qualitative studies and case studies were excluded. Systematic reviews were excluded but their reference lists were searched to capture relevant literature. Interventions targeting other health behaviours were excluded.

The team adjusted the inclusion criteria in response to the emerging thematic analysis. The team expected explicit identification of partnerships in studies but adjusted this when the partnership was implied but not named. Studies where a local government and health service partnership were not clearly described but implied the organisation's involvement were included. Program involvement was suggested by the health service assistance with recruitment18 and displaying signage to encourage physical activity.19

Studies where the health promotion program did not specifically target adults aged 45 and over were included if the mean or median participant age was at least 45 years or if more than 50% of the study sample was at least 45 years. Ells et al was included as 43% of participants were aged 55+.18 Where a study met all inclusion criteria apart from participant age (mean age 35.7 years) it was included.20

2.2 Data extraction

The following data were extracted from identified studies by the first author: publication year, country of study, type of study, organisations involved, program eligibility criteria, program description, length, frequency and duration of sessions and program, cost, level of supervision provided, physical activity, healthy eating or related health outcomes.

The quality of papers was appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklists18, 20, 21 each conducted by two reviewers (Reviewer 1 and one of the Reviewers 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) with discrepancies resolved by discussion and consensus. The overall certainty of evidence for each outcome was assessed with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for narrative synthesis22, 23 by one reviewer (Reviewer 1).

The program content was assessed by the presence of behaviour change techniques (BCT), which are “an observable, replicable, and irreducible component of an intervention designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behaviour; that is, a technique is proposed to be an ‘active ingredient’”24 (Table SS1). BCTs were coded using the BCTTv1 taxonomy by a reviewer (Reviewer 1) who had completed the online training of the BCT taxonomy.25

2.3 Strategy for data synthesis

Findings were summarised by one reviewer (Reviewer 1) through a narrative synthesis. Effect sizes (Cohen's d, Cohen's h) were calculated for reported physical activity and healthy eating outcomes for all studies if sufficient data were available. As studies included in this review used heterogeneous study designs and statistical methods, meta-analysis was not possible. Findings were summarised by partnership roles, program target groups, program development, BCTs and study design, as the effects of programs on outcomes may have differed based on these characteristics and based on the key questions addressed in this review.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Search results

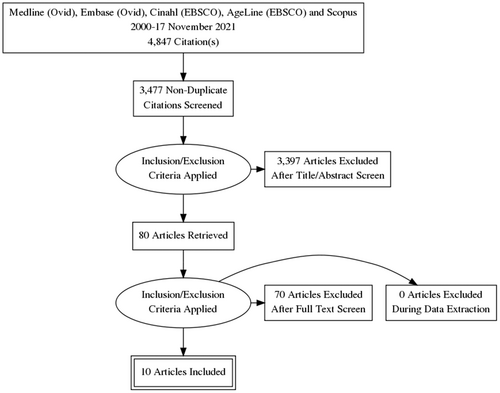

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow of studies selected through the review. The search obtained a total of 4847 records, including an additional five records obtained through hand-searching reference lists of relevant literature reviews. After deduplication, there were 3477 records, following title and abstract screening there were 80 studies.

A total of 10 articles were identified after full-text screening: two randomised controlled trial articles,26, 27 two quasi-experimental articles28, 29 and six observational study articles.18-20, 30-32 One study was reported in two articles.28, 29 Characteristics of the studies and study populations are shown in Table 1. Studies were conducted in the UK,18, 26, 30, 32 Australia,19, 20, 31 the Netherlands28, 29 and USA.27 Study duration was a median of 18 months with a total of 19 802 participants recruited and a median of 68.5% females.

| Study | Country | Study design | Study length | Study recruitment | Participant numbera | Age, years, mean (SD) | Female, % | Inclusion, exclusion criteria | Study limitations reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barham et al27 | USA | RCTb | 12 months | Enrolment in program | 45 | 51.2 (8) | 84 | Adult employees, diagnosed Type 2 diabetes, or score ≥ 10 on American Diabetes Association risk questionnaire | Small sample size; biases with self-reported outcomes; 3-month comparison group; lack of assessor blinding |

| Byrne et al19 | Australia | Observational | 7.5 years | Random selection from population register | 879 | 59.3% >45 years | 53c | Resident of Launceston with a landline telephone number | Data were collected at major events, incomplete data; biases with self-reported outcomes; nonresponse bias; bias towards individuals who had a telephone landline likely resulting in higher proportion of older participants; lack of control group |

| Ells et al18 | UK | Observational | 12 months | Retrospective data analysis | 2027 | 42.8% >55 years across Services B, C, D, G | 75d | Services B, C, D, G; Adults over 18 years; BMI ≥ 25; without comorbidities or have managed comorbidities. Excluded: BMI ≥ 35 with significant unmanaged comorbidities; bariatric surgery within past 2 years |

Inconsistencies in data collection; potential for reporting bias; only one county in the UK investigated |

| Harrison et al26 | UK | RCT | 12 months | Enrolment in program | 545 | 60% >45 years | 66.6 | Referral by primary health care professional or local diabetes centre; sedentary (<90 min weekly MVPA); CHD risk factors. Excluded: contraindications to PA, HT, not sedentary |

Study did not investigate the possible impact on nonphysical activity outcomes |

| Hetherington et al31 | Australia | Observational | 8 weeks | Enrolment in program | 2827 | 58.4 (14.22) | 78 | Residents across 67 local government areas wanting PA and healthy eating programs. Excluded: risk identified on pre-exercise screen and contraindication/s to PA verified by health care practitioner |

Lack of control group; low retention rate; men were underrepresented in the sample group |

| Higgerson et al30 | UK | Observational | 7 years | Retrospective data analysis | 6160 | NR | NR | People living, working or registered with a GP in Blackburn with Darwen | Measuring attendance at leisure facility is subject to error; biases in self-reporting/recall; unable to distinguish whether outcomes differed for different recruitment methods used; unable to assess impact of the intervention on activities outside leisure facilities |

| Penn et al32 | UK | Observational | 12 months | Enrolment in program | 218 | 53.6 (6) | 68.5 | Adults 45-65 years living in central Middlesbrough, UK; elevated risk of Type 2 diabetes (FINDRISC assessment tool); no Type 2 diabetes diagnosis | Underrepresentation of ethnic minority groups; no objective measures for T2D in recruitment, flexibility in recruitment criteria by trainers |

| Ronda et al28 | The Netherlands | Observational | 3 years | Random selection from population register | 1444 | 48.5 (16.42) | 50.7 | Aged over 14 years; living in the Maastricht region or the reference region |

Low baseline response rate (55.5%); high dropout rate (31.5%); bias with self-reported outcomes; possible lack of sensitivity of single-item CVD risk assessment tool; survey questionnaire size; lack of randomisation |

| Schuit et al29 | The Netherlands | Observational | 5 years | Random selection from population register | 3895 | 50.9 (9.85) | 51.8 | Sample drawn from sub-population sample of adults aged over 30 years; living in the Maastricht region or the reference region. Excluded: moved to another region during 5-year study period |

Lack of randomisation; possible biased sample who were previously involved in health research |

| Wen et al20 | Australia | Observational | 2 years | Random selection from population register | 1762 | 36.6 (NR) | 100 | Resident of Concord local government area with telephone connection; Female; aged 20-50 years; able to answer questionnaire in English | Lack of control group; selection bias towards women with a listed telephone number; results may not translate to different socioeconomic areas; limited financial and human resources for the narrow target group |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CHD, coronary heart disease; MVPA, moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity; NR, not reported; PA, physical activity; SB, sedentary behaviour.

- a Participant number at baseline.

- b RCT for 3 months, all participant results pooled thereafter.

- c Mean percentage of three cross-sectional timepoints.

- d Mean percentage across three service areas.

At least half of the articles met 6 of the 14-item CASP checklist for cohort studies. The cohort was representative of the defined population in eight articles (Item 2).19, 20, 26-30, 32 In six articles, the length of follow-up of subjects was adequate (Item 6b)19, 26-28, 32, 20; and statistical precision was used in reporting results (Item 8).19, 20, 26, 27, 30-32 Half of the articles addressed a clearly focused issue (Item 1)20, 26-28, 31; measured the outcome accurately to minimise bias (Item 4)19, 26, 27, 31, 32; and stated the practical implications of the study (Item 12).20, 26, 27, 31, 32 The overall certainty of evidence (GRADE) was very low for physical activity, healthy eating and related health outcomes (Table 2).

| Quality assessment | Summary of findings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | No. of studies (design) | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Physical activitya | 1 (RCT) 6 (observational) |

Low | Low | Very low | Very low | Low | 13 835 (7) | Ꚛ ○ ○ ○ Very low |

| Healthy eatingb | 2 (observational) | Low | Low | Low |

Very low | Low | 4271 (2) | Ꚛ ○ ○ ○ Very low |

| Related health outcomesc | 1 (RCT) 2 (observational) |

Low | Low | Low | Very low | Low | 5967 (3) | Ꚛ ○ ○ ○ Very low |

- a Self-reported physical activity outcomes via questionnaires recording duration, frequency, and intensity.

- b Self-reported healthy eating outcomes via questionnaire or estimated average daily serves of fruit, vegetables, or fat intake.

- c Related health outcomes measuring body mass index, waist circumference, or blood pressure.

3.2 Partnerships

3.2.1 Roles

In addition to the local government and health service partnership, other organisations including universities, government and nongovernment agencies were involved in delivering health promotion programs. Organisational roles in the identified studies are shown in Table 3. Most notably, organisations provided program funding in the identified studies, there was no evidence of conflicts of interest with funding received from health industry partners. Organisations were also involved in program development and implementation, recruitment and referrals to the programs and coordinating staff and volunteers.

| Study, program length | Program participants | Program descriptiona | Program personnel | Program designb | Program partnershipc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barham et al27 USA 12 weeks | Target: Employees Recruitment: Individual email invitation via workplace |

Weekly face-face education group program for healthy eating, physical activity, stress reduction. Provided with equipment and resources to self-monitor behaviour | Management: Study nurse Delivery: University-employed nurse educator, dietitian, psychologist, physical therapist |

Framework: Adapted curriculum from the DPP, the National Diabetes Education Program (www.diabetesatwork.org) and used conversation maps from Healthy Interactions Inc. Development: Program adapted from a previous workplace program by authors |

Roles: COUNCIL: Funding, recruitment HEALTH SERVICE: Funding, provided worksite room for sessions, supported staff participation during lunchtimes, employee recruitment OTHER: University employees delivered program Development: No details |

| Byrne et al19 Australia 7 years | Target: General population Recruitment: Community marketing |

Active Launceston program. Promoted active transport, provided diverse and free physical activity programs/events with professional support to ensure safe participation | Management: Five staff Delivery: Industry personnel (including yoga instructors, personal trainers), sports clubs and university students |

Rationale: Multi-strategy and wide-scale, service-oriented approach Development: No details how program of pre-existing activities and events was developed |

Roles: COUNCIL: Funding HEALTH SERVICE: Signage on stairs in health service OTHER: University funding, State government funding, endorsement of programs by 60 organisations Development: No details |

| Ells et al18 UK 12 week “rolling basis” | Target: Adults with BMI ≥25 Recruitment: Self-referral or individual referral from health care professional |

One face-face group session to promote physical activity. Access to a multi-component program (education, exercise, telephone, online support) |

Delivery: Across the 7 services, staff had level 3 weight management and physical activity training; 2 services employed staff qualified in nutrition; 4 services were supported by dietetic services |

Rationale: Tier 2 Multicomponent program as an integral part of the local weight management care pathway. Framework: 40-item CALO-RE taxonomy evaluated behaviour change content of service Development: No details how program was developed |

Roles: COUNCIL: Funding; initiated pilot testing the program. HEALTH SERVICE: Health care professional referrals Development: No details |

| Harrison et al26 UK 12 weeks | Target: Sedentary adults with additional CHD risk factors Recruitment: Individual referral from primary health care professional |

Intervention: Exercise Referral Scheme (1 h face-face tailored advice), written information and subsidised leisure facilities pass. Comparator: written information and subsidised leisure facilities pass only |

Delivery: Leisure centre-employed exercise officers |

Rationale: Evaluation of current national practice of Exercise Referral Schemes Development: No details how Exercise Referral Scheme was developed |

Roles: COUNCIL: Funding scheme HEALTH SERVICE: Funding scheme Development: No details |

| Hetherington et al31 Australia 8 weeks | Target: General population, aimed to capture low SES Recruitment: Community marketing |

HEAL program Weekly face-face group education and exercise program promoting physical activity and healthy eating, providing resources (adapted for people with low literacy and CALD) and home-based exercises |

Management: Delivery: Healthy Communities Coordinator employed for each council area Delivery: Allied health professional facilitators trained and assessed in program delivery |

Rationale: Implement the government Healthy Communities Initiative. Theory: Education content based on Transtheoretical Model and Stages of Change (Prochaska et al 2013) Development: Program was developed by the health service, recipients of the government grant |

Roles: COUNCIL: Council applied for Government funding, employed coordinator HEALTH SERVICE: Developed HEAL program, funding application, recruitment OTHER: Government funding; ESSA partnership with health service for funding application Development: Partnership development by proxy. Government grant initiative to support local governments deliver evidence-based community programs. Local governments opted to run the program |

| Higgerson et al30 UK N/A | Target: General population Recruitment: Community marketing; offer of trial and buddy |

re:fresh scheme Free use of leisure facilities. Access to health trainers to promote physical activity |

Delivery: 5 health trainers employed over 7 years to offer goal setting, motivational interviewing to individuals or groups. 2 Community workers supported a network of volunteers engaging people in leisure facility trial sessions |

Rationale: Free access to government leisure facilities to address inequalities of cost Development: No details how re:fresh scheme was developed |

Roles: COUNCIL: Funding HEALTH SERVICE: Funding OTHER: NHS funding for 6 years; University funding; Community volunteers to run awareness-raising community events Development: No details |

| Penn et al32 UK 10 weeks | Target: General population, aimed to capture low SES Recruitment: Community marketing |

NYNL program. Twice weekly face-face group physical activity program, cookery sessions, group discussion, online newsletters and postprogram online support and “drop-in” sessions |

Delivery: Local authority employed fitness trainers |

Framework: Program based on authors' previous RCT and developed in reference to UK National Social Marketing Centre benchmark criteria, designed for adults living in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas. Stakeholder consultation for program design. Trainers delivered “behaviour change strategies” as required. Development: Program developed in consultation with stakeholders |

Roles: COUNCIL: Funding, employed fitness trainers, leisure-centre based program HEALTH SERVICE: Funding, recruitment OTHER: NGO funding, University funding Development: No details |

| Ronda et al28 The Netherlands 3 years Schuit et al 200629 The Netherlands 5 yearsd | Target: General population with lower SES Recruitment: Community marketing |

Hartslag Limburg program, community-based activities and events to promote physical activity, healthy eating, smoking cessation; resource provision | Management: Health Committee supported by a health educator, social worker, civil servant of the municipality | Rationale: Collaboration between the the community and local organizations, linking the health-promoting initiative, a social network approach, an environmental strategy and a multi-media and multi-method strategy. Development: Each Health Committee organised activities to facilitate healthier lifestyles |

Roles: COUNCIL: Funding, council staff on Health Committee HEALTH SERVICE: Member of the Health Committee OTHER: Funding by Regional Public Health Institute Maastricht, 2 community social work organisations, community health care organisation and local organisation and representation on Health Committees to promote activities. Study funded by Netherlands Heart Foundation Development: Community analyses conducted prior to the official start of the project to introduce the project in the communities, achieve early community involvement, and assess which people, organizations and community sectors to approach for participation in the Health Committees. 9 Health Committees (each with ~10 members) set up across region, meeting ~10 times/year |

| Wen et al20 Australia 2 years | Target: Women aged 20-50 years in general population Recruitment: Community marketing |

“Concord, a Great Place to be Active” campaign. Community-based activities and events to promote physical activity; resource provision | Delivery: Council members, 3 project staff and community sectors |

Rationale: Response to input from the target group, stakeholders and community Development: Program developed by Project Advisory Group |

Roles: COUNCIL: advisory group, use of facilities for meetings, stationery HEALTH SERVICE: Funding, representation in project advisory group OTHER: Community sector representation in the Project Advisory Group Development: Project commenced with focus groups conducted with the target group and community feedback sessions. Project Advisory Group representing council, health and community sectors was formed. Community Advisory Group representing the target group, councillors, council staff member, 3 project staff was formed to guide implementation of the program. Council capacity was fostered via membership in Groups, use of council resources and facilities, alignment of project with council's social/environmental plans |

- Abbreviations: CALD, culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds; HEAL, Healthy Eating and Lifestyle program; NGO, non-government organisation; NLNY, New Life New You program.

- a No cost charged for programs in identified studies.

- b Program design: details of the rationale, theory, framework or development.

- c Program partnership: details of the partnership role/s or partnership development.

- d Ronda 2004 and Schuitt 2006 report outcomes from Hartslag Limburg program.

3.2.2 Nature of partnership

Three studies described organisations working collaboratively to deliver the program.18, 20, 31 Four studies described programs were co-designed with stakeholder consultation to ensure they were relevant and appropriate for the target group and the personnel delivering the programs.20, 28, 29, 32

The studies reported that it was not only feasible for multiple organisations to work collaboratively, but a partnership was necessary to deliver a health promotion program. Multifaceted, integrative input from a variety of organisations19, 29 was deemed necessary to address both the health behaviour18, 26, 31, 32 and environmental,19, 27 organisational19, 20, 26-30 and policy changes31 to support healthy lifestyles.

Two studies described some features of how partnerships were developed prior to program development. Early involvement of stakeholders and formation of committees helped to support communication and collaboration.28, 29 The flexibility to align the program with local government priorities was another suggestion to build capacity of organisations.20

3.3 Programs

3.3.1 Health behaviour and recruitment

Characteristics of the programs are shown in Table 3. Nine programs were described since two studies evaluated the same Hartslag Limburg program.28, 29 Four programs promoted physical activity and healthy eating27-29, 31, 32 one of which targeted individuals who displayed health risk factors.27 Five programs promoted physical activity alone,18-20, 26, 30 two of which targeted individuals via health care professional referrals.18, 26 All other programs recruited via community marketing.

3.3.2 Development

Three programs were developed with collaborative stakeholder input such as end-users, personnel delivering the program, local government and health service personnel and the community sector.20, 28, 29, 32 Two programs were designed using previous research or a behaviour change framework27, 31, 32 and one program was designed with both collaborative input and previous research.32 Four studies did not describe program development.18, 19, 26, 30 One study reported program resources were further adapted for people with low literacy, non-English speaking backgrounds, and people of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander backgrounds.31

3.3.3 Format: Behaviour change techniques

BCTs, the active ingredients used in each program that drive behaviour change, were coded and presented in Table 4. The number of coded BCTs ranged from 4 to 9.32 Across programs, social support (BCT3.1) and information about health consequences (BCT5.1) were most commonly coded, followed by repetition/practice of the health behaviour (BCT8.1). Where programs offered participants multiple modes of delivering activities from which to choose to increase their engagement, it is possible not all participants in the population studies received each of the coded BCTs.18-20, 28-30

| Category of behaviour change techniques | Barham et al27 | Byrne et al19,a | Ells et al18,a | Harrison et al26 | Hetherington et al31 | Higgerson et al30,a | Penn et al32 | Ronda et al28,a, Schuit et al29,a | Wen20,a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2 | 2 | |||||||

|

1 | ||||||||

|

1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

|

1 | 1 | |||||||

|

2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

|

1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

|

1 | 1 | |||||||

|

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

|

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

|

1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

|

|||||||||

|

1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Total behaviour change techniques | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 4 |

- Note: BCT: “an observable, replicable, and irreducible component of an intervention designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behaviour; that is, a technique is proposed to be an ‘active ingredient’” (Michie et al.24).

- a Population-level program.

3.4 Study appraisal and program impact

Due to the heterogeneity of study designs and statistical methods, the overall impact of the identified programs could not be analysed. Reported study limitations are presented in Table 1 and a description of study appraisals and postprogram outcomes are below and summarised in Table 5.

| Study | Participant no.a | Retention rate | Follow-up post baseline | Outcomes, measurement tool | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barham et al27 USA | 45 | 91% | 0, 3, 6, 12 months | PA: IPAQ HE: % fat intake BMI, waist circumference, BP, eating behaviour |

At 12 months, program participants reported: Improved PA (P = .011, d = 0.5) Improved HE (P = .018, d = 0.4) Weight lossd (P < .001) Decreased BMId (P < .001) and waist circumferenced (P = .004) |

| Byrne et al19 Australia | 879 | N/Ab | 0, 4.5 years (2012), 7.5 years (2015) | PA: items from Exercise Recreation and Sport Survey and National Healthy Survey Exercise | Program participants reported no change in PA participation for exercise, recreation or sport over past 12 months in 3 data collection timepoints (P = .91, Walking d = 0.08). |

| Ells et al18 UK | 2027 | 40%c | 0, 3, 6, 12, 18 months | Weight collected at point of service usage | At 3 monthsd: Greater weight loss (5%) recorded in program participants aged 35-54 years and those with no co-morbidities. Lowest weight loss recorded in program participants aged 55+. Significant difference between these age groups (P = .001) At 6 monthsd: Proportions of weight loss maintained but no associations between weight loss and age, gender, socio-economic status Data unavailable for 12, 18-month follow-up |

| Harrison et al26 UK | 545 | 57% | 3, 6, 9, 12 months posted | PA: 7dPAR questionnaire | At 6 months, between-group difference of 9% reported doing ≥90 min/week MVPA (P = .05, d = 0.3), favouring program participants At 12 months, no between-group difference of 5.4% reported doing ≥90 min/week MVPA (P = .18, d = 0.2) |

| Hetherington et al31 Australia | 2827 | 61% | 0, 8 weeks | PA: questions based on “Active Australia Survey” HE: estimated average daily serves of fruit, vegetables Height, body mass, BMI, waist circumference |

At 8 weeks, program participants reported: Increased PA level and frequency (d = 0.4), reduction in SB (d = 0.2) (P < .001) Increased daily serves of fruit and vegetables consumed (P < .001, d = 0.4) Reduced body mass (d = 0.04), BMI (d = 0.07), waist circumference, BP (diastolic BP, d = 0.2), improved functional capacity (30 s chair rise d = 0.5) (P < .001) |

| Higgerson et al30 UK | 6160 | N/Ab | Leisure centre data 2005-2014, APS annual survey data 2005-2014 (ex. 2006) |

PA: secondary data analysis, Active People Survey, national annual survey of sports participation | Scheme introduction associated with 64% increase in leisure attendance (RR 1.64, 95%CI 1.43 to 1.89, P < .001)d Greater overall PA participation and leisure centre attendance in most disadvantaged SE group |

| Penn et al32 UK | 218 | 61% | 0, 6 months, 12 months | PA: PA levels and type assessed by PA diary instrument used in the European Diabetes Prevention trial HE: average daily portions fruit, vegetables, type of bread, milk, fat Weight, waist measurement, FINDRISC |

At 12 months, program participants reported: Increased total PA (d = 0.02) Increased gym-based PA participation (h = 1.0) Increased HE (daily portions fruit/vegetables: 2 or less, h = 0.7; 5 or more, h = 0.5) Reduced weight (d = 0.3), waist circumference (d = 0.2) |

| Ronda et al28 The Netherlands | 1444 | 62.8% | 0, 2 yrs, 3 yrs | PA: validated short questionnaire calculating PA in minutes and sessions/week, frequency of 30 min PA/week HE: validated questionnaire calculating fat consumption score |

At 3 yearsd, participants reported: No between-group difference for PA Lower fat score for participants in intervention region compared to those in reference region, attributable to younger age (<49 years) |

| Schuit et al29 The Netherlands | 3895 | 83% | 0, 5 years | CVD risk factors, BMI, waist circumference | A 5 yearsd, participants in the program region demonstrated lower BMI, waist circumference, BP (P < .005) |

| Wen et al20 Australia | 1762 | N/Ab | 0, 2 years | PA: duration, frequency, intensity of PA over past 2 weeks | At 2 years, participants reported: Reduced sedentary time (h = 0.2), Increased low PA (h = 0.1) |

- Note: d, effect size, Cohen's d; h, effect size, Cohen's h.

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; INDRISC, Finnish Diabetes Risk Score; HE, healthy eating; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; MVPA, moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity; PA, physical activity; SB, sedentary behaviour; 7dPAR, 7-day Physical Activity Recall questionnaire.

- a Participant number at baseline.

- b Not applicable due to study design, eg, random cross-sectional samples recruited, yearly trends in pooled data.

- c Retention at 6 months. Data reported for 4 of the 6 Services.

- d Insufficient data in identified study to calculate effect size.

Two randomised controlled trials were identified.26, 27 Harrison et al reported the impact of exercise advice and 12-month leisure facility subsidies for sedentary adults referred from the primary care setting in a large randomised controlled trial. Assessor biases were minimised, but the retention rate was low. The trial found a small between-group effect size for the proportion doing at least 90 minutes of weekly moderate-vigorous physical activity, favouring the intervention group at 6 months postrandomisation, but the effect was not maintained at 12 months postrandomisation. Barham et al reported the impact of a 12-week pilot worksite lifestyle program for overweight employees (n = 45).27 There was high retention but risks of bias due to unblinded assessors and lack of adjustment for confounders in analysis. A moderate effect size was detected following the program in improved self-reported physical activity, lower dietary fat intake and reduced weight, waist circumference and BMI for the intervention group. Pooled results at 12 months from baseline, showed 12.5% (n = 5/40) participants had at least 7% body weight reduction.

Quasi-experimental studies evaluating the Hartslag Limburg program were reported by Ronda et al28 and Schuit et al.29 The physical activity and healthy eating program compared outcomes between an intervention region and reference region. At 3 years after program commencement, participants in the program region showed lower fat consumption scores but no difference for self-reported physical activity.28 At 5 years after program commencement, participants in the program region had lower body mass index, waist circumference and blood pressure.29

Two observational studies, offering defined activities in the program were identified.31, 32 Hetherington et al reported the HEAL program, an 8-week physical activity and healthy eating program conducted in local government areas amongst the general population (n = 2827), had a 61% retention rate.31 Analyses did not adjust for confounders but following the program, there was a moderate effect size for increased self-reported physical activity, daily serves of fruit and vegetables and functional capacity from baseline measures, and minimal effect size for reduced body mass index, waist circumference and blood pressure. Another short program was reported by Penn et al who conducted a feasibility study of New Life New You (NLNY), a 10-week physical activity and cookery program and provided postprogram online and “drop-in” session support for people with type 2 diabetes risk factors.32 Participants were followed up over 12 months. The retention rate was 61% and analyses did not adjust for confounders. Following the program, a large effect size was demonstrated for participation in gym-based physical activity and daily portions of fruit and vegetable consumption, small effect size for reduced weight and waist circumference and a minimal effect size for increasing overall physical activity.

Two observational studies offering the population a range of activities within a physical activity program were identified19, 20 and reported modest outcomes. The Active Launceston initiative showed little change in physical activity participation over the previous 12 months at 3 timepoints.19 The “Concord, a Great Place to be Active” campaign yielded a small effect size for sedentary time reduction and increased low-intensity physical activity at 2 years after program commencement.20

Retrospective data analyses were conducted by Ells et al 2018 and Higgerson et al.18, 30 Overall, access to a 3-month multicomponent physical activity and support program resulted in 5% weight loss, seen greatest in adults aged 35 to 54 years and least in adults aged over 55.18 Free use of leisure facilities in the re:fresh scheme over a 7-year period resulted in 64% increase in leisure centre attendance. The proportion increased the greatest was for people in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic group.30

4 DISCUSSION

The review of the literature is necessary to best inform the strategic development of an Australian health promotion service. This is the first review to evaluate the evidence for physical activity and healthy eating health promotion programs for middle-aged adults delivered in partnership by the local government and local health service. The review revealed a scarcity of quantitative studies that use the same methodologies to measure outcomes for future pooling on the topic. The majority of studies were pragmatically designed, observational, cohort, population-based studies which resulted in a relatively low retention rate. Overall, the studies lacked methodological rigour, were rated as low-quality evidence and did not control for biases making it impossible to draw firm conclusions about efficacy. Nonetheless, the review yields some useful insights about partnerships and physical activity and healthy eating health promotion programs and their development and effectiveness.

This review identified roles of the local government and health service partnership in delivering health promotion programs: funding, membership on project committees to develop programs, provision of program staff or recruiting participants and the involvement of nonfunding organisations and volunteers. Key roles such as these have also been described by Corbin et al in their study of intersectoral partnership roles across broad health promotion topics.33 Their review found that elements of a successful partnership considered the process of input (eg, partnership and financial resources, mission), throughout (eg, leadership, communication, finding the balance between financial input and volunteers) and output (eg, additive results versus collaborative results) of the partnership.

A necessary and important process to program design and delivery was multifaceted organisations working with an integrative and collaborative approach. This approach enabled stakeholder partnerships to deliver a coordinated and multifaceted program to the population. Gillies reported a collaborative approach for alliances and partnerships in broader health promotion programs was more likely to result in a larger impact on health outcomes.12 A partnership with a collaborative approach that enabled a broader tackling of the determinants of health and well-being and set agendas for action at a community level and reported for health promotion programs on both a micro, individual level and a macro, systems level.12 The nuance of a collaborative approach and an effective partnership requires a mutual and skilful communication between organisations throughout the partnership.11 This approach enables organisations to work synergistically, balancing the partnership with their goals, rather than working merely alongside each other.33 The broader health promotion literature also describes social capital as another feature of effective partnerships, which was not identified in this review.12 The informal structure of civic engagement, social networks and interpersonal relationships is integral to promoting healthy behaviours and an important partnership resource.

Well-designed health promotion programs informed by an evidence base are essential34 but were poorly reported by studies in this review. An evidence base is necessary since firstly, changing health behaviour is complex35 and crosses several disciplines such as psychology, sociology, anthropology and economy.36 By systematically drawing from an interdisciplinary evidence-base, strategies can best be applied to support the adoption and maintenance of healthy lifestyles. Secondly, there are limited and often declining resources relative to the size of the global problem of NCDs and competing health and policy priorities.37 It is therefore essential that health promotion programs are well designed, evidence based and can demonstrate efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability upon implementation.

A notable design feature of health promotion programs for middle-aged adults in this review was presence of BCTs embedded into the program. Programs with a higher number of coded BCTs reported moderate to large effect sizes for physical activity and healthy eating outcomes.32 Combining the elements of partnerships and programs, a health promotion program that is developed collaboratively and informed by an evidence base or behaviour change theory is a promising approach for designing future health promotion programs.

4.1 Implications and recommendations

The key implications and recommendations from this review are the importance of the “who,” “how” and the “what” of program development. The “who” refers to partnership organisations involved in delivering health promotion programs. For community-based health promotion program, partnership organisations need to be involved in the community,12 such as local government and health services, and involve groups that represent the community such as local organisations and volunteers. It is important these multiple organisations are involved from an early stage of the project as they are key to helping support, promote and deliver the program. “How” organisations develop a program requires a collaborative approach from these multiple groups. Strategies to ensure clear communication such as program committees are recommended to enable joint input to program development.

The “what” of program development is the content of the program. A program designed and substantiated by an evidence base of research or framework of behaviour change will be the essence that drives physical activity or healthy eating. There are resulting implications for programs which offer multiple modes of delivering activities, aiming to best appeal to people's ranges of preferences. Careful and detailed design with a behaviour change framework for each of the activities is needed to support individuals adopt and maintain physical activity and healthy eating behaviour and to impact NCDs such as falls, obesity, cancer, depression in the longer term.

Another implication from this review is the feasibility of directly implementing newly designed programs into pre-existing facilities and making use of staff expertise. Not only is this approach resource-efficient but such lifestyle modification programs have the potential for sustainability and scalability and the potential to inform policy development in these settings.19, 28, 29 Efficacy testing and improved data collection within a service model are needed in settings that use pre-existing facility and staff resources so that programs can be translated into routine practice.38

While this review focussed on physical activity and healthy eating health promotion programs, this is only part of the picture of promoting health behaviours at a community and local level. Other systems-level issues can also be addressed through partnership at a local level, such as urban design and planning, but this was outside the scope of the present review.

This review highlights the need for efficacy studies in this partnership space. Future well-designed studies which accurately report methodologies, partnership and program details are needed. In addition, further research is needed to explore the process of partnership development.

4.2 Strengths and limitations

This is the first rapid systematic review of health promotion programs delivered by a local government and health service partnership and has highlighted the evidence gap in this partnership space. The review was guided by the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods and PRISMA-ScR Checklist. The review protocol was preregistered on Open Science Framework prior to the review process.

A limitation of this study was the review process may not have captured all the relevant literature in this field. The Cochrane guidance for rapid reviews is to limit grey literature and supplemental searching.15 While excluding the grey literature was a limitation our search followed the guidance and limited database searching by selecting two relevant biomedical (Medline, Embase), two relevant specialist (CINAHL, AgeLine) and one multidisciplinary (Scopus) database. Another limitation of this rapid review was lack of a second reviewer for data extraction validation.

5 CONCLUSION

This review highlights the heterogeneity and scarcity of quantitative evidence evaluating health promotion programs delivered by a local government and health service partnership for middle-aged adults. The review highlights features of a partnership such as a collaborative approach, and features of program design such as an evidence base can best support the uptake of physical activity and healthy eating behaviour. While these studies provided limited guidance on how to develop partnerships, this question could be answered by further investigating qualitative studies and the grey literature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Anne Tiedemann for proofreading the final manuscript. This work was funded by the Health Promotion Unit, Sydney Local Health District. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley - The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

APPENDIX

Ovid MEDLINE Search strategy

| # | Search |

|---|---|

| 1 | exp aged/ or middle aged/ |

| 2 | (aged 45* or aged 60*).tw. |

| 3 | (older adult* or older worker* or older people or older person or older persons or middle age* or postmenopaus* or post menopaus* or community dwell* or community living* or senior* or elder*2).tw. |

| 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 |

| 5 | health promotion/ or weight reduction programs/ |

| 6 | (health promotion or weight loss or weight reduc*).tw. |

| 7 | exercise/or physical conditioning, human/ or running/or jogging/ or swimming/or exp walking/or exp physical fitness/ |

| 8 | dancing/ or sports/or bicycling/or tai ji/or yoga/ |

| 9 | exp healthy lifestyle/ |

| 10 | ((healthy eating or healthy diet or healthy ag#ing or physical*2 activ* or active ag#ing or lifestyle or “life style” or community or exercis*3 or sport or sports or fitness or physical condition* or danc* or swim* or run* or jog* or walk*3 or cycl* or bicycl* or yoga or tai chi or t'ai chi or tai ji or behavio*5 or health or wellness or wellbeing or “well being” or public health) adj2 (promot* or strategy or strategies or service or services or prevent* or program* or campaign or campaigns or initiative or initiatives or intervention or interventions or policy or policies)).tw. |

| 11 | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 |

| 12 | Local Government/ |

| 13 | ((city or cities or council or councils or shire or shires or borough or boroughs or municipal*3 or district or districts or county or counties or metropolitan or unitary or parish or parishes or village or villages or neighbo#rhood or neighbo#rhoods or township or townships or territor*3 or regional or local*3) adj2 (government or governments or authorit*3 or jurisdiction or jurisdictions)).tw. |

| 14 | 12 or 13 |

| 15 | 4 and 11 and 14 |

| 16 | limit 15 to “humans only (removes records about animals)” |

| 17 | limit 16 to yr = “2000 -Current” |

| 18 | limit 17 to English language |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.