Using the Ophelia (Optimising Health Literacy and Access to Health Services) process as a practical tool for health promotion program delivery in various Philippine communities

Abstract

Issue Addressed

The Ophelia (Optimising Health Literacy and Access to Health Services) process can be used as a practical tool for effective health promotion program delivery because of its multi-sector and pragmatic approach to designing health interventions. An initial case study showed how its first phase was successfully adapted in a pilot community in Leyte, Philippines. In this study, the three phases of the Ophelia process were implemented in Leyte, along with additional communities in Mindoro and Surigao.

Methods

After conducting needs assessment and community profiling in phase 1, the results were transformed into vignettes, hypothetical personas representing the health needs of the community. These were used in phase 2, which involved focus group discussions and workshops to cocreate intervention ideas with government organisations, practitioners, and community representatives. A rapid realist review was conducted in phase 3 to check for the feasibility of interventions.

Results

Through this, the top evidence-based health interventions for each life stage were listed and presented for prioritisation. Program implementation and impact evaluation plans were created for the top health intervention prior to implementation.

Conclusions

The Ophelia process ensured that health promotion interventions addressed community needs and were designed using community resources and the wisdom of health practitioners that have been immersed in the local health system.

So What?

The study demonstrated the usefulness of vignettes in presenting data to lay people and how the rapid realist review approach is a practical tool for policy-makers to ensure that program plans designed by the communities and health practitioners are evidence-based without sacrificing the timeliness of implementation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) like the Philippines face special challenges compared to high income countries to be able to address public health goals. Effective interventions in LMICs must consider and respond to local needs, resources and contexts.1 The Optimising Health Literacy and Access to Health Services (Ophelia) process aims to achieve this in three phases, namely: (i) Needs Assessment, (ii) Cocreation, and (iii) Intervention Trials with the communities.2 The Ophelia process is a way to develop health literacy interventions grounded on the needs of a community, relying heavily on the collaboration of multiple stakeholders and community members to “improve health and equity by increasing the availability and accessibility of health information and services in locally-appropriate ways.”3 The study aims to evaluate its practicality as a Health Promotion Tool for the Philippines with emphasis on collaboration, taking into account the local context and community wisdom. In 2017, the Ophelia process was implemented for the first time in chosen communities in the Philippines through this study, enabling the different stakeholders from the Department of Health (DOH), local government units (LGUs), health practitioners, and community members to work together by cocreating and implementing evidence-based interventions for better health outcomes.4

Needs assessment was done using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) and the Information and Support for Health Actions Questionnaire (ISHAQ). The HLQ and the ISHAQ are multi-dimensional surveys that provide practitioners, organisations and governments the health literacy strengths and limitations of individuals and populations in their areas with the latter more appropriate for LMICs.1

Cocreation with stakeholders is the second phase of Ophelia and this activity has been proven to effectively engage communities and discover novel health interventions.1 A study in Egypt showed that participants had a deeper understanding of their problems, challenges, resources, and negative impacts on health through the stories of people they recognise. This in turn enabled them to generate low-cost local solutions.5

The last part of the Ophelia process is the implementation of select interventions chosen based on the available health and social resources to ensure its sustainability and scalability. By doing so, a decrease in operating costs, increase in staff availability and an empowered local community should be expected.1 An example of this was in Thailand where they used Thai humour to effectively raise public attention about taboo subjects such as contraception and HIV awareness.1 Another example of this is capitalising on the culture of the community. In South Africa, the cocreation sessions featured common principles like respect local wisdom, encourage self-determination, and build local capacity to allow the interventions to be more effective.1

2 METHODS

2.1 Setting

This was a multi-site multi-phase study on health literacy for select Philippine communities. The communities were chosen based on the human development index (HDI) per geographic zone (i.e., Luzon, National Capital Region or NCR, Visayas, Mindanao). The province closest with the whole zone's median HDI was selected, with HDI values from 2009 as reported by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) with ranking done in 2018.6 The choice to select the median HDI province was to achieve representativeness of the zone by the province in the absence of random sampling. The province of the median HDI per zone was chosen to represent each of the four zones. NCR and the province in Luzon had the high HDI classification while the areas in Visayas and Mindanao assumed the low HDI classification. After identifying the case provinces, the municipalities were purposively chosen by considering the established political support in the area. In each of LGU, population groups were tapped through organisations (e.g., schools, livelihood centres, and primary health centres). Stages were purposive since the Ophelia process relies on the participation of the community. The sampling also took into account the recommendation of the DOH Health Promotion Bureau (DOH HPB) based on their knowledge of community statuses.

2.2 Participants

Representatives from the different life stages: breastfeeding mothers (for newborns), children, adolescents, adults, and seniors were included. Practitioners from the DOH, and the Department of Education (DepEd), local government officers representing each life stage, city health officers, nurses, midwives and nutrition officers were invited in the study.

2.3 Sampling

The samples for phase 1 survey respondents for HLQ (Leyte) and ISHAQ (Mindoro and Surigao) were computed using the formula for proportion.7 The prevalence estimates used were from existing surveys done in the Philippines. Estimates for behaviour were used, and not the prevalence of health literacy, since the study was focused on the change in health behaviours. The sample ranged from 54 to 91 participants per life stage. This yielded a minimum of 270 per area. Random sampling would be counterproductive to the research objectives given the interventional nature. Hence, the study used purposive sampling in the selection of community settings. The willingness criteria did not pose a problem of selection bias because: (i) the study does not aim for representativeness; (ii) there is no control group; and (iii) this was supposed to be a paired sample design (i.e., before and after comparisons will be done for each community). Informed consent forms (ICFs) were translated into local dialects, disseminated, and accomplished ICFs were collected from the participants or their guardians prior to inclusion in the study. A total of 1578 survey respondents for all three areas participated in phase 1 of the study.

Several focus group discussions (FGDs) were also conducted in phase 1. The first FGD round was to get an initial profile of the communities through 8–10 community members, based on the qualitative sampling rule of thumb for FGDs.8 The second phase also involved FGDs with one session for each life stage representing community members, while cocreation workshops were conducted for organisational representatives and health practitioners.

2.4 Data collection

2.4.1 Community profiling and needs assessment

The Needs Assessment was done using the World Health Organization (WHO) community profiling tool,9 Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) for Leyte, and the Information and Support for Health Actions (ISHAQ) for Mindoro and Surigao. It was made up of indicators for socio-demographic characteristics, health behaviour, environment, social cohesion, and information relevant to the community and life stage involved. The descriptive information helped inform priority setting and motivate actions to address health issues.

The HLQ measures health literacy along nine domains, based on the framework of the Health Literacy Management Scales (HeLMS).10 HeLMS defined a two-level conceptual framework based on (i) six core individual abilities required to seek, understand, and use information in the health care setting, and (ii) 11 extrinsic and intrinsic contextual factors that underpin these abilities.10 Like the HLQ, the ISHAQ was created to measure the strengths and limitations of individual and population health literacy.11 After consultation with the developers of the tool, a decision to change tools from the HLQ to the ISHAQ was recommended for the remaining sites. This ISHAQ was not yet ready for use by the time the study was started but was later recommended for adoption in the remaining sites due to its suitability for LMICs such as the Philippines as it takes into account decision-making in settings where it occurs as a collective activity.

Both the HLQ and the ISHAQ were translated to the local dialect with two forward translations, one back translation, and a translation conference. This process was based on the translation integrity procedure of the tool creators.9 After the translation was finalised, a pretest was conducted to assess the reliability of the translated tools. A minimum of 30 participants were invited to participate and the reliability of the tools were computed using Cronbach's alpha test where alpha >0.90 was considered reliable for this study. All translated tools were deemed reliable after the first pretesting.

2.4.2 Cocreation and program planning

Participatory action research design was used during the second phase. Each life stage had designated vignettes which were presented to the organisation leaders and health practitioners through cocreation workshops, and community members through separate FGDs per life stage. Participants were asked to reflect and suggest solutions to the health problems identified in the stories. They were also involved in the planning and design of the interventions during data collection and analysis, thus becoming partners in the research process.12

2.4.3 Rapid realist review

The ideas for interventions addressing the needs presented in the vignettes were generated by the FGDs, which then went through a rapid realist review (RRR) of existing literature on effectiveness of the proposed health interventions. An RRR was used instead of a realist synthesis (RS) proposed in Ophelia due to the limitations in time and resources of the study. The difference between RS and RRR was the breadth of the search process to the point of theory saturation.13 The RRR was done through different teams of reviewers per intervention. Steps on conducting RRR were based on Saul et al.13

The shorter turn-around time and the involvement of an expert panel from local stakeholders in the RRR was the better fit for Ophelia as implemented in the Philippines (Ophelia Philippines) involving the organisation, practitioners, and community members in all three phases. The review resulted in summarising evidence-based interventions that could help improve the health outcomes of different life stages, presented using Context-Intervention-Mechanism-Outcome (CIMO) diagrams.14

2.5 Analysis

2.5.1 Needs assessment: Profiles and cluster analysis

The Ophelia process utilised univariate analysis and cluster analysis in phase 1. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, showed the distribution while proportions and frequencies presented the composition of a sample based on a set characteristic. For the 9 HLQ or the 14 ISHAQ domains, means and standard deviations were used to present the scores for each domain.

Cluster analysis was done to determine the groupings of similar participants and to aid in vignette writing. Within a cluster, the individuals are homogenous while among the clusters, the profiles and characteristics are heterogeneous. Ward's hierarchical approach was used as it held the criterion of minimised variances. The approach was an iterative bottom-up clustering where the individuals started as one group then divided further into significant subgroups iteratively until the variance per cluster was minimised to a set number. After the cluster analysis, the narrative data from semi-structured interviews were integrated with the findings alongside their HLQ or ISHAQ domain scores (see Table 1).

| Cluster description | |

|---|---|

| Cluster | 1 |

| Count | 17 |

| Mean Age | 67.59 |

| SD Age | 7.16 |

| Count (Female) | 10 |

| % Females | 58.80% |

| ISHAQ scales (0–10) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Knowledge about service entitlements | 9.13 |

| 2 | Awareness of resources that support health in your neighbourhood | 8.9 |

| 3 | Ability to access health services | 8.6 |

| 4 | Ability to get the information and advice you want from health professionals | 9.49 |

| 5 | Close support people | 9.53 |

| 6 | Ability to find suitable health information | 9.13 |

| 7 | Evaluating the trustworthiness of health information | 9.51 |

| 8 | Accepting responsibility for health | 9.43 |

| 9 | Eating for health | 9.434 |

| 10 | Exercise for health | 8.75 |

| 11 | Managing stress | 9.59 |

| 12 | Using medicines | 9.3 |

| 13 | Using herbs and supplements | 9.43 |

| 14 | Travelling barriers and ability | 8.43 |

| 15 | (Chronic Illness) Exchange experience and knowledge with other patients | 8.76 |

| 16 | (Chronic Illness) Self-monitoring | 9.24 |

- Note: Background: A typical person in this cluster is a 67-year-old female living in Surigao with her family. Most are Filipino speakers who attained differing levels of elementary school education. These seniors are tasked with taking care of household duties with some even noting that they are permanently unable to do other types of work. There are many chronic illnesses, such as: arthritis, back pain, heart and lung problems, as well as diabetes. Despite this, only few have health insurance or a health card. Health seeking behaviours for this cluster are generally good. Most are able to manage stress (scale 11), have the benefit of a close support group (scale 5), and are able to access and evaluate the trustworthiness of health information (scale 7). Even with these, however, these women still have difficulty accessing health services (scale 3), especially with the hardship of travelling to access these (scale 14).

2.5.2 Cocreation: Thematic analysis and rapid realist review

The vignettes were written using the cluster analysis results and the narrative data, creating hypothetical personas who had the same health issues and abilities as the people who were in the clusters. A specific template was used for both the background and the vignette itself. For the background, a short profile of the typical person in the cluster is shown, including the age, gender, education level, health card status and common health ailments. At the end, the highest and lowest scales for the specific cluster were identified. Once a background of the cluster was written out, the vignette was then made with one persona used as a representative of the entire cluster of respondents. The persona was described based on a common name in the community, age, marital status, educational level, number of dependents, and any identified health ailments. Afterwards, by using the identified highest and lowest scales, a common situation was written out wherein the persona practices health literacy (using the highest scale) and also a scenario wherein the person may have difficulty in practicing health literacy (focusing on their lowest scale).

Separate cocreation workshops were conducted for different groups of stakeholders. The first group consisted of health practitioners and organisation representatives or leaders such as school nurses, municipal health officers, midwives, barangay health workers, Office for Senior Citizen Affairs representatives, Livelihood Training officers, teachers, and nutrition officers. The second group consisted of representatives from the community members, with each life stage having a separate FGD to discuss vignettes representing their life stage using the Ophelia template and resources for cocreation.2 This separation of groups was also recommended by the Ophelia creators to ensure that the community members would not have difficulty expressing their opinions and ideas, since they might not be comfortable to share if health practitioners and organisation representatives or leaders were present.

- Do you see people like this or do you know people like this?

- What sort of issues is this person facing?

- What strategies or solutions could help this individual overcome the issues?

- Is the intervention idea likely to be equitable (can they be applied to a lot of people?)

- Is the intervention idea sustainable?

- Is the intervention idea exciting?

- Are there major risks (negative effects or problems the person or the community might encounter) if this idea was implemented?

- What are the available resources in the community that could help in the implementation of the intervention?

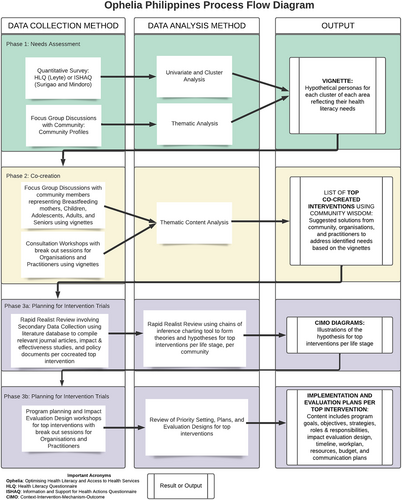

Content analysis of the FGD results was done to show the most common interventions suggested by practitioners and community members per life stage, as illustrated in Table 2. Organisation and health practitioner representatives were heavily involved in the health program planning, design, and impact evaluation for monitoring and sustainability of the interventions chosen. The team of reviewers also conducted the secondary data collection for phase 3a (see Figure 1). This part of the process reflected steps four to eight of the 10 steps of the RRR Method discussed previously. For each top intervention per life stage, the reviewers produced the following.

| Top interventions per life stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Children | Adolescents | Adults | Seniors |

| Seedling distribution per household or backyard gardens | Proper solid waste management including trash offence in barangay and clean-up program | Family counselling. Includes normalise family bonding for strong foundation of support system; Division of Labor/Scheduling of house works and other responsibilities. Application of proper time management principles for household chores with parents | Provide job opportunities and livelihood trainings like garments and food processing to alleviate stress and provide income | Monthly doctor's visit or other health personnel for check-up, counselling, and health related updates to the home or health centre (Community Health Counseling—to motivate people to visit RHU/hospital for health consultation) |

| Home visit by nurses for check-up and health information dissemination; encourage her to seek health care services in the health facility | Practice and promotion of healthy eating habits (lessen sweets and street foods, eat nutritious food) in schools and homes. This includes selling of nutritious foods in canteens | Sex Education and Health Awareness (importance of check-ups and management) Campaign in school or community; includes online workshops | Gardening and beautification per house (with evaluation)—Assembly meeting for backyard gardening campaign, free seeds from DA | Promote Herbal Gardening in the backyard |

| Health Information and Education Campaign per barangay using IEC materials | Free medicine and health check-up (annual) from barangay or medical missions | Home visitation—Health staff household visit for free check-up and health update and pandemic news dissemination | Health assistance for free consultation in barangay health centres with different doctors with different specialties; designated health workers for each barangay (doctors, midwives, nurses) | Provision of free personal health protection during pandemic |

| Assign more nurses and doctors in the community and barangay health centres for barangays without one | Family health counselling with committee on health, including couple counselling. Topic can also include financial literacy promotion | |||

- Note: For Surigao, there were a total of three top interventions for breastfeeding mothers, four top interventions for children, three top interventions for adolescents, four top interventions for adults, and three top interventions for seniors.

Literature review database

There were four reviewers involved in coding using a Literature Review (LR) database. For each life stage, there were two reviewers. The review answered questions about how the interventions worked in other countries with similar profile, the population, context, and how they succeeded in implementation.

The reviewers were assigned the top three to four interventions for each life stage based on the list of interventions collected during Ophelia phase 2 in the cocreation FGDs. These top interventions were those suggested by both the community members and the health practitioners. In the event that interventions were not agreed upon by the two different groups, the ones suggested by the community were prioritised. The reviewers used an iterative approach in searching for the concepts.15

- Population—specific life stage (breastfeeding mothers, children, adolescents, adults, seniors).

- Intervention—the top intervention resulting from the co-creation, described using Medical Subject Headings or MeSH terms.

- Comparator—not applicable.

- Outcome—Improved health and wellbeing or Improvements or increase in health literacy outcomes.

- Study Design—impact studies, effectiveness studies.

Countries located in the WHO WPRO region were prioritised and papers written in the English and Filipino language were considered. The documents should also have been published within the last 10 years. The research team used databases like Google scholar and Pubmed to search for sources. Individual LR database for each life stage was created based on a uniform template. Each article found was categorised under each intervention that initially came from the list of top interventions gathered during the co-creation FGDs.

Chains of inference charting tool and rapid realist review synthesis

The LR database was then downloaded and auto-coded into themes using NVIVO software. The resulting themes and sub-themes were used to create the Chains of Inference (COI) theories. These were then validated by the field team. Contrary evidence was already included, if found at all by the reviewers, even before the themes were made.

The connections or COIs across extracted data and themes were sought. This is an iterative process and connections were updated as needed. There was no formal rule of which should be filled up first—COI theory level, COI sub-theory level, or themes from the literature—given the iterative process, so the Qualitative consultant prescribed the intervention ideas from the FGDs as the sub-theory coming from the co-creation FGD members, since it was still too generic and needed to be broken down further by the reviewers using the literature.

Hypothesis formation was the last step and was done using the filled-up COI theories, sub-theories, and themes. At this stage, the hypotheses reflect the intervention ideas that came from the co-creation FGDs with additional details from the thematic analysis of the literature database. The reviewers were able to identify possible relationships and health outcomes for the interventions, along with specific activities for the health intervention in the COI theories. Since the interventions have yet to be implemented and the actual health outcome is yet to be seen, the evidence-based interventions are called hypotheses.

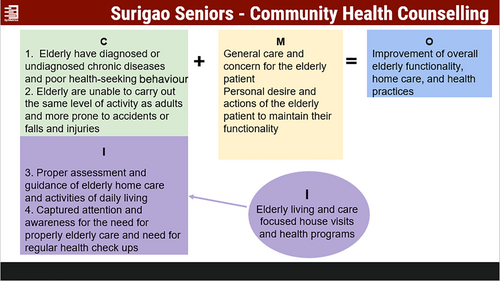

Rapid realist review synthesis report containing CIMO diagrams and summary tables

The research team used Google Sheets for the LR database, Chains of Inference and Hypothesis statements, NVIVO software for thematic analysis, and Google slides for the Context-Intervention-Mechanism-Outcome (CIMO) diagrams (see Figure 2). These CIMO diagrams were used to present the top evidence-based intervention ideas along with the context and mechanisms needed for it to work, and the final health outcome desired, to the health practitioners and leaders that were invited for the program planning workshop during phase 3.

3 RESULTS

In applying the Ophelia process in the Philippines, a wealth of data from the communities were gathered through primary and secondary data collection. In this article, we present the results for each phase by focusing on one actual output per phase. Through this, the overall Ophelia process flow would be better understood, illustrated in Figure 1.

3.1 Phase 1

Prior to any data collection conducted in partner communities, a Health Literacy Workshop was done for local health practitioners, including school nurses, and organisation representatives. The training focused on providing community stakeholders with a better understanding of health literacy and to give an overview of the Ophelia process. Due to the health literacy seminars given at the start of each site entry, the Ophelia process helped local stakeholders understand the implications of health literacy on their experience with their health system. Workshop participants from Mindoro expressed that the training enabled them to gain health literacy skills to manage their health better even just from their own home.

This phase included two methods: (i) a health literacy questionnaire via the HLQ or the ISHAQ and (ii) an FGD with stakeholders from the community to create a community profile. The total number of respondents per area are as follows: Leyte (578), Mindoro (565), Surigao (514), while the total number of community profiling FGD participants per area are: Leyte (47), Mindoro (40), Surigao (40).

Below is an example of a cluster analysis results with its corresponding vignette.

3.1.1 Output 1: Vignette

The persona of “Lolita” is representative of the results of one entire cluster (Box 1). At the end of the study, the number of vignettes per life stage, per area, are as follows: Leyte (32), Mindoro (27), and Surigao (26).

BOX 1. Vignette (Surigao seniors)

Lolita is a 67-year-old female who lives with her youngest daughter and grandchildren. Lolita only finished elementary school. At home, she usually tends to home duties she is still able to do, like cleaning and cooking. She has her children and grandchildren near her for help and to keep her company. She has a lot of friends within her barangay, so there are a lot of people she can rely on for support. Lolita also has access to radio broadcasts and online news, as reported to her by her grandchildren. They are aware of fake news and how to verify if reports are true or not. Lolita has arthritis and diabetes; she and her daughter have a hard time managing these illnesses. They mostly rely on the free health check-up from a visiting doctor who only comes twice a year because the travel expense to go to the local health centre and the out-of-pocket expenses for medical consultations and prescriptions add to the financial burden of their family. Lolita mostly relies on herbal and home remedies to relieve her symptoms.

3.2 Phase 2

For Leyte, a total of 23 participants attended the co-creation workshops designed for health practitioners and organisation representatives. Mindoro had a total of 37 co-creation workshop attendees while Surigao had a total of 14. For the separate co-creation FGDs for community members that was divided per life stage, Leyte had a total of 51 participants, Mindoro had a total of 155 participants, while Surigao had a total of 40 participants.

3.2.1 Output 2: List of top interventions per life stage

The results of the co-creation focus group discussions with the community representatives and the results from the co-creation workshops with the organisation representatives and health practitioners were analysed using content analysis. Table 2 shows the resulting top interventions for Surigao.

3.3 Phase 3

3.3.1 Phase 3a

In Leyte, a total of 13 hypotheses were generated (2 for breastfeeding mothers, 3 each for children, adolescents, and adults, and 2 for elderly). For Mindoro, a total of 16 hypotheses were generated (3 for breastfeeding mothers, 4 for children, and 3 each for adolescents, adults, and the elderly). For Surigao, a total of 17 hypotheses were generated (3 for breastfeeding mothers, 4 for children, 3 for adolescents, 4 for adults, and 3 for the elderly).

3.3.2 Output 3: CIMO diagram

Figure 2 is an example of a CIMO diagram based on the evidence found that stemmed from the community health counselling intervention from the co-creation FGDs conducted using Lolita's vignette.

3.3.3 Phase 3b

For each life stage per location, workshops were held with representatives from local stakeholders to select the top interventions and plan the implementation. Key decision makers from the LGU, relevant institutions, and community leaders were invited. The workshop covered selecting the most feasible intervention, planning its execution, impact evaluation, communication, and scaling up. All these were documented in a program proposal for each similar to Table 3, a sample proposal from Surigao.

| Program title | Surveillance for elderly patients to improve their quality of life and overall functionality and independence |

| Rationale | An intervention that was feasible to implement during pandemic restrictions was chosen to be trailed for phase 3, to see if it would have a positive impact on the health outcome of seniors in del Carmen, Surigao del Norte |

| Location | Del Carmen, Surigao del Norte |

| Duration | July 2021, 2022 |

| Funding and resources needed | Funding: PHP 20 000 Resources: letter, email SMS, social media and radio Kabakhawan and brgy. announcement |

| Who will the program benefit? | Seniors |

| Goal and objectives | Goal: To improve elderly's quality of life in Del Carmen by engaging them to recreational activities and conducting home visits Objectives: 1. To regularly monitor the health status of all seniors in Del Carmen 2. To promote a healthy lifestyle for all seniors in the community |

| Program strategies and activities | 1. Regular physical activity like Zumba exclusive for seniors in every barangay 2. Free monthly consultations and distribution of food supplements among Seniors 3. Create a radio segment for health tips to all seniors in the community |

| Impact evaluation design | A pre and post intervention nonexperimental evaluation design would be implemented, where a sample of the seniors who were involved in the health education meetings will be interviewed before and after the program to assess the program's impact |

| Communication plan | Letter, email SMS, social media and radio Kabakhawan and brgy. announcement |

- Note: The workshops resulted in 12 program proposals across life stages in the three areas. Program proposals for all life stages were completed in Mindoro and Surigao. Only proposals for children and adolescents and senior citizens were accomplished in Leyte due to administrative delays.

Examples of programs that focused on health literacy among those aimed at children upon RRR in Palo, Leyte are the inclusion of health topics in meetings for parents, teachers to become sources of health information to their children, and creative presentation training for nurses and teachers to package health information tailored to their pupils. Meanwhile, interventions in Socorro, Mindoro included ensuring proper solid waste management to improve health outcomes, ensuring zoning and sanitary compliance of piggeries, and reinforcing adherence to COVID health protocols. Finally, several interventions in Del Carmen, Surigao del Norte centre on preventive care, such as providing free annual medical consultations and medicines to children, and targeting key healthy behaviours in school and at home to prevent the emergence of disease.

4 DISCUSSION

The results of the study show how the Ophelia process is a practical tool for Health Promotion program delivery in the Philippines. The use of tools that reflect the country profile and culture and the co-creation sessions using vignettes resonated well with the communities of all three areas with all the life stages represented.

4.1 Practical use of ISHAQ for Philippine country profile

The ISHAQ was created specifically for LMIC settings so this was used for Surigao and Mindoro. The 14 scales of the ISHAQ take into account collective or community decision making for health which is a better fit for the culture of the Philippines. The ISHAQ is also offered free of charge for use by governments as opposed to the HLQ which comes with a high administration fee for LMICs. By understanding health literacy needs, effective interventions can be developed and existing interventions can be improved.17

4.2 Why co-creation is important and practical

There have been other initiatives in improving health literacy such as digital health literacy initiatives in Europe,18 assessment toolkits in the United States19 and various other assessment and information toolkits. Similarly, there have been initiatives in creating tools for co-creation for health.20-22 However, Ophelia is currently the only existing framework specifically for assessment and co-creation of health literacy interventions through co-creation. In the second phase, collaboration with all the relevant stakeholders was done through the co-creation process. Representatives from the different organisations and practitioners of each life stage participated in the co-creation workshops to create solutions or interventions that address the needs assessment results. These were compared with the solutions or interventions that came from the community representatives of each life stage, ensuring that community wisdom was also included as seen in Table 2. The vignettes presented during these workshops were practical tools for lay people to understand the needs assessment results in the form of a story about a person that they can relate to. The successful implementation of Ophelia phases 1 and 2, needs assessment and co-creation, are important steps towards increasing access to health services and also increasing health literacy. These are systematic and efficient approaches that ensure the use of available resources in the community to improve population health.23 A similar project by Loignon et al.24 which involved co-creating solutions with the different stakeholders in the community also showed how this kind of participatory approach can help “increase their access to health services.”24

Since the study was done on a large scale with all the life stages represented in several communities at the same time, the researchers added activities to complement the Ophelia process as needed in the Philippines' unique setting. This includes capacity building workshops and the adoption of RRR to ensure evidence-based interventions will be proposed to the communities in a timely manner.

4.3 Capacity building of stakeholders

The principles of Ophelia Philippines are aligned with that of the Universal Health Care (UHC) Law, which aims to “ensure that all Filipinos are health literate” and to “provide all Filipinos access to a comprehensive set of quality and cost-effective, promotive, preventive … health services.”25 Beginning with a needs assessment and community profiling to gain a more comprehensive understanding of each community is strongly in line with taking a people-oriented approach which recognises the context of different communities.25 Similarly, several training workshops were conducted at the start of each phase to help contribute to the basic understanding of health literacy among participants for each life stage. These included health literacy training workshops, co-creation workshops, program planning workshops, and impact evaluation workshops. Aside from health practitioners, organisation representatives, and community leaders, local area coordinators and research staff fluent in the local language were also trained to ensure that the Ophelia process is shared and disseminated to all the stakeholders.

4.4 Rapid realist review as a practical approach for policy makers

Results of Ophelia Philippines may aid the Philippine DOH HPB by providing locally-tailored, evidence-based interventions that may be piloted and evaluated for refinement and potential scaling up, with a focus on health literacy, health promotion, and preventive care, as recommended in the UHC Law. The rapid turn-around of the results generated using the rapid realist review approach ensures the timely release of potential interventions reflecting the actual needs of the communities.

4.5 Using the Ophelia process as a tool for generating health promotion interventions

Ophelia is a feasible approach to develop interventions tailored to the health literacy needs of a specific population and a specific focused disease. Ophelia implementation in Europe, Australia, Asia, and the Philippines encountered different factors contributing to the success or failure of implementing the method in full scale. Similar challenges encountered are time constraints, barriers in the implementation, continuity of an intervention, and organisation's flexibility to accommodate interventions.26 Past Ophelia implementations in the mentioned countries recommended a longer time-frame for capacity building, intervention trials and impact evaluation. Overall, Ophelia has enabled all study sites to generate health-literacy informed interventions.

While there was variation to the co-created interventions across areas, as they were tailored to each community's specific needs, it may be noted that many interventions were not solely medical or clinical, and in fact used a multidisciplinary approach that involved environment, financial, and social aspects of the community. Examples of these are livelihood skills training programs, health insurance literacy training, setting up a waste segregation program and materials recovery facility and gardening and beautification programs. These may be said to be aligned with a “whole of society approach,” promoted in the UHC Law as well, as they involve families, local government, and local organisations and businesses.25

The WHO initiated National Health Literacy Demonstration Projects (NHLDPs) in Denmark, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, and Slovakia where Ophelia was used to inform evidence-based interventions in schools, communities, and hospitals for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) like rheumatic conditions, COPD, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and renal diseases.26 In contrast, Ophelia Philippines focused on the promotion of breastfeeding among mothers, nutrition and WASH among school age-children, sexual and reproductive health among adolescents, healthy diet and exercise among working adults, and mental health or prevention of dementia among the elderly.

It is hoped that by their experience and participation in Ophelia Philippines, local stakeholders gain knowledge and skills in health literacy and health promotion. The project aims to have provided local partners with the capacity to be able to replicate the process or otherwise use the related skills in new or existing programs related to local health promotion. Though the study was not able to conduct the trial of interventions, interventions were chosen based on available health and social resources to ensure sustainability and scalability. By doing so, a decrease in operating costs, increase in staff availability and an empowered local community should be expected.1

Similar key challenges have been observed across LMICs, and suggested action points reflected the interventions in Ophelia Philippines. Globally, women in LMICs often have “less personal autonomy, and less access to information about their health than do their male counterparts.”1 Key barriers to their health include long distances from facilities, lack of trust and quality provided by the health system, and other limited number of trained health care providers and properly-equipped facilities.1 Thus, solutions such as making information and services for family planning, pre- and postnatal care, immunisation, and child health more available and accessible were also suggested by the WHO.1 In Leyte, community support groups aim to increase health literacy to empower mothers. Information on services will also be available through mass media to increase family planning practices. For Mindoro, nutritional knowledge will help achieve the goals identified. Lastly, community health workers will be engaged in Surigao to increase health care accessibility for breastfeeding mothers as long-distance facilities were reflected to be problems for both maternal and child health.

Evidence shows that those in LMICs carry a greater disease burden.1 Interventions such as fitness programs, information sessions and activity engagement, home care visits and surveillance across the three areas answers the current problems and challenges to increase access and availability of information and services. Overall, Ophelia Philippines reflected common strategies found in other LMICs and identified similar challenges to health literacy and existing problems for developing countries.

4.6 Limitations

Since this was the first time Ophelia was implemented in the Philippines, Leyte was chosen as the pilot area while the other areas were added only after the first phases were done in Leyte. This resulted in the implementation schedule of the other areas coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic and why only the first part of phase 3 was completed. The fourth site, Parañaque City (designated as the high HDI area) suffered from an extended strict lockdown, therefore research activities could not be implemented and the area removed from the study. The team was able to instead conduct a program planning workshop (see Table 3), create impact evaluation plans for the top interventions, and conduct an impact evaluation training workshop. These training workshops equipped the areas in conducting their own impact evaluation even after the Ophelia study ends, promoting sustainability.

4.7 Bias

- Selection bias and lack of external validity due to use of convenience sampling in participant recruitment. The results of the HLQ and ISHAQ were profiles of the community that cannot be generalised to the population. However, the nature of the Ophelia process is to explore the environment and resources of the community down to the individual level.

- Information bias, specifically outcome misclassification because of the use of subjective measurements with the survey answers reliant on the participant's own understanding of the question. Exposure misclassification is expected to be null for some demographics (e.g., education and employment). However, variables related to medical history may have some misclassification as we only asked the participants’ personal knowledge of their own morbidities. We did not validate this with any clinical diagnosis. This may bias the profile written in either direction (e.g., underestimation or overestimation). However, the most common diseases were used in the vignettes which were further validated upon consultation with the community.

- Confounding was not considered in the cluster analysis as it specifically grouped participants according to the tool domains. Clusters were primarily determined using their health literacy and the profile of the respondents were only used further in the vignette writing. Note that adjusting for confounders is only crucial when estimating relationships. Phase 1 results were only to describe the profiles of the participants and not with the aforementioned.

Such biases and confounding are expected to minimally affect the internal validity of the results. The methodology of Ophelia does not aim external generalizability but to contextualise results in a specific community.

5 CONCLUSION

This study showed how the Ophelia process can be a practical tool for health promotion program delivery in different Philippine communities. We were able to identify the health literacy needs of different life stages through the HLQ and eventually the ISHAQ, which was then used to create vignettes that portray the community's health needs in a more personal and relatable way. All of the relevant stakeholders were not only informed, but also engaged with the co-creation of effective and sustainable solutions through the platform provided by the Ophelia process in the second phase. Collaboration and partnerships representing the LGU, DOH, DepEd, local health or municipal centres, local health practitioners, barangay officials, and community representatives for different life stages is hard to achieve without the help of the Ophelia process. This is in line with the three requirements of effective health promotion (HP) program delivery—(i) collaboration and partnerships, (ii) health interventions targeting both individual and population supported by capacity-building strategies, and (iii) clear identification of key stakeholders or partners.27

Since the top interventions from the co-creation workshops and FGDs were based only on the wisdom and knowledge of the relevant stakeholders from the community, RRR was conducted to find evidence of their effectiveness in other countries with similar geographical profiles in a timely manner. This is another key element in the Ophelia process that showed how evidence could be processed effectively without sacrificing the quality due to the time constraints usually experienced by local governments in program implementation. Finally, knowledge transfer was also done during the capacity building workshops with the representatives from different organisations and practitioners. The Ophelia process provided the avenue for capacity building opportunities, ensuring the sustainability of the health interventions.27 This is critical for successful implementation because the individual practitioners are needed to plan and evaluate health interventions that take into consideration the community needs and interests and roles of other stakeholders.28

A separate manual describing the Ophelia Philippines study methods was created to be used as a guide for policy makers replicating the project. The Ophelia Philippines manual provides a comprehensive jump-off point for other organisations to replicate the project in their respective communities. Researchers should consider using the story or hypothetical persona format of the vignettes in activities similar to the co-creation workshop and in other health promotion research, to help the participants effectively understand, relate to, and contribute to solve the problem.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Abigail Lim Tan, Stephanie Anne L. Co, Cheyenne Ariana Erika M. Modina, Christine Ingrid M. Espinosa, Krizelle Cleo Fowler, and John Q. Wong contributed to the conception or design of the work, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, article drafting, and final revision of the article. Abigail Lim Tan, Stephanie Anne L. Co, Cheyenne Ariana Erika M. Modina, Christine Ingrid M. Espinosa, Krizelle Cleo Fowler, and John Q. Wong approve of this final version of the article to be submitted. Nonauthor contributors comprise of the EpiMetrics, Inc. team who contributed in the conception, data collection, and technical supervision for the analysis and article writing. The authors would also like to acknowledge Ms. Joya Bagas, our previous research associate.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The original study entitled “An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the OPtimising HEalth LIterAcy (Ophelia) Process in Improving Health Literacy Across Chosen Life Stages” was awarded to EpiMetrics Inc. by the Philippine Department of Health's Health Promotion Bureau through the AHEAD HPSR grant.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval from the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB) was granted for the original study entitled “An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Optimising Health LIterAcy (Ophelia) Process in Improving Health Literacy Across Chosen Life Stages.”

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.