“Healthy Kids”—A capacity building approach for the early childhood education and care sector

Abstract

Issue Addressed

Queensland children have a higher level of developmental vulnerability compared to the Australian average. This paper reports on Healthy Kids—a capacity building strategy for the early childhood education and care (ECEC) sector targeting communities experiencing socio-economic and child development vulnerabilities. These communities may face additional barriers when engaging and participating in health promotion models. This paper reports on the development, key components and principles of a capacity building model referred to as Healthy Kids, that strategically responds to these barriers and supports these communities.

Methods

The development of the Healthy Kids model emerged through a quality improvement process that included an environmental scan, and review of existing capacity building, health promotion, and workforce development approaches. It also involved consultation and engagement with the ECEC sector.

Results

Evidence indicates Healthy Kids to be an innovative health promotion model focussed on building capacity through a workforce development strategy for the ECEC sector in a way that is accessible, low cost, and sustainable.

So What?

This paper shares a model for building capacity through the establishment of localised cross-sector communities of practice across a large geographic region with a centralised coordinating hub. The hub and spoke model has facilitated community ownership to grow and be sustained over time. This model offers opportunities for partnerships, transferability, and contextualisation for those interested in contemporary health promotion, capacity building, and workforce development. The model offers an approach for those willing to step outside traditional boundaries to work across sectors and settings to achieve sustainable knowledge and skills, processes and resources that enables a collective commitment to improving health outcomes.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is widely established amongst the health, neuroscience, and education fields that the first 2000 days of a child's development (from conception to a child entering formal schooling) are crucial in setting the foundation for lifelong learning, behaviour, health and developmental outcomes.1 Early foundations have complex connections with growth, learning and development, and a trajectory that extends beyond adolescence into adulthood.2 Many educational and health issues faced during adulthood including cardiovascular disease, obesity, mental health concerns, educational attainment and employment opportunities, have their roots during the critical period of development in early life.3, 4 Conversely, positive habits and behaviours formed early can impact on later good health and wellbeing.5-7 Despite this growing understanding of the significance of the early years,8 there is still work to be done to support children during this period.

The Centre for Children's Health and Wellbeing, a multi-disciplinary team, focused on addressing health inequities and reducing the impact of social determinants of health, were tasked with building capacity to improve school readiness in 10 communities across Queensland experiencing higher levels of socio-economic and developmental vulnerability. At a national level, developmental vulnerability is defined as a child identified as being in the lowest 10% in at least one of the five developmental domains: physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills and communication skills and general knowledge as outlined and measured by the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC).9 This data provides a holistic picture of how children are developing during their 1 year of formal education10 throughout each state and territory, including Queensland children.

AEDC figures consistently indicate that children in rural and remote areas of Australia are twice as likely to start school developmentally vulnerable compared to their metropolitan counterparts. Data is not uniformly distributed across the nation, with 2021 AEDC data10 indicating that while the gap has narrowed, Queensland vulnerability rates continue to be higher than the national average. Queensland communities with even higher levels of developmental vulnerability (on one or more domains) were prioritised for Healthy Kids. This paper describes Healthy Kids, an initiative implemented to support Queensland communities in addressing children's early development prior to school.

1.1 The ECEC sector—A key setting for influencing children's health and wellbeing

Young children spend an average of 5000 hours a year awake with a significant amount of time spent in environments such as the home and in early childhood settings.8, 11, 12 Research attests that high quality ECEC services have a significant impact on children's cognitive development, school readiness skills, and the progress and performance of children once they attend school,13 as well as across the life course. There is also evidence that high quality ECEC has even greater benefits for children from disadvantaged backgrounds and low-income families.14-16

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) is consistently identified as a critical setting for promoting and facilitating children's health, development, and wellbeing.17, 18 Within Queensland, and more widely, there has been rapid growth in the number of children attending ECEC services, particularly over the last two decades, with figures indicating an increase of 35%-45% in 2000 to almost 65% in 2021.19, 20 Given the combination of ECEC contexts being significant sites of impact, and the escalating attendance of children in ECEC settings, it makes sense that strategic approaches are focussed on supporting the ECEC workforce, and the key stakeholders who care and work with young children, particularly those located in communities experiencing vulnerability,21 in order to positively influence a child's health, development and wellbeing.22

Key to the provision of high-quality education and care are staff qualifications and access and support to participate in ongoing professional learning.23 In Australia, evidence suggests that the “health and safety” quality area of the national quality standards (NQS) (quality area 2) is the area that services are least likely to rate “Exceeding National Quality standard”, and more likely to be rated “Working Towards National Quality Standard”.24 This indicates there are opportunities for sector improvement in the ways in which educators create supportive environments and experiences as they are well positioned to play a critical role in making a difference to the health and wellbeing of young children.25, 26 There are also opportunities to lift national standards related to “health and safety” to embrace the integration of a range of health promotion strategies across the ECEC sector.27

1.2 Capacity building

Capacity building is recognised as a key approach within health promotion “to improve practices and infrastructure by creating new approaches, structures or values which sustain and enhance the abilities of practitioners and their organisations to address local health issues”.28 Models that embrace capacity building describe the importance and commitment of partners, as well as resource mobilisation, trust between partners, clear partnership arrangements, good communication, and mutual benefits for sustainable outcomes.

However, at this point the evidence-base regarding health promotion in ECEC is limited, with few studies that document health promotion practice with associated outcomes.29, 30 Additionally, studies in health promoting early childhood environments have identified collaborative, “relationship-focused” partnerships between health and community agencies and early childhood services as integral to the success of a health promotion intervention.25 At the same time, barriers to participating in community capacity building include high-level resourcing, other associated costs, and limited time to establish and maintain relationships.31 There are also contextual factors at a community level such as geographic diversity, accessibility, and lack of resourcing to champion and build on strengths within the community that also impact on capacity building.

Healthy Kids was built on public health theories and frameworks1, 32-34 to create an effective evidence-based capacity building approach for the ECEC sector. This approach addressed the identified barriers whilst building local ownership. The key goals were to: (i) increase early childhood educators' capacity and knowledge of child health and development, (ii) support the integration of this knowledge into daily practice, (iii) enhance the health of the children and families they serve, and (iv) to achieve these goals whilst keeping costs to a minimum. This paper describes the development, key principles, and components of the Healthy Kids model.

2 METHODS

Healthy Kids began in 2016 as a quality improvement project and given that it was not specifically a research project, ethical approval was not sought at that time. In 2021 ethics approval was granted for retrospective access to feedback surveys as part of a broader research project by Children's Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), and the University of Southern Queensland, to support exploration of the efficacy of Healthy Kids as a workforce development strategy. Healthy Kids provided an opportunity to trial a workforce development strategy that aimed to build the capacity of early childhood educators to support healthy development in children.

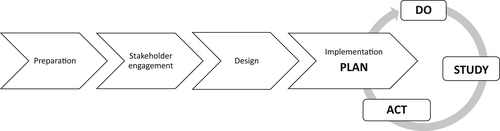

Healthy Kids evolved through a continuous quality improvement process, allowing the model to be refined during implementation. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Model for Improvement using plan–do–study-act (PDSA) cycles helped guide the improvement process.35 Figure 1 shows the development of the Healthy Kids model.

2.1 Preparation phase—Environmental scan and review

Conducting the environmental scan was an integral part of informing the development of the Healthy Kids model. It provided contextual insight and background information on the ECEC sector; areas of priority for children's health; and professional learning. The scan helped to identify gaps and avoid duplication, competition, or overlap of similar professional development (PD). The environmental scan also helped identify the current sector-specific priorities for PD and provided evidence to guide decision-making and planning.

The process involved a desktop scan of existing PD activities offered to the sector by statewide networks and peak representative bodies, and noted any costs associated with attendance. Additionally, key stakeholders provided the project team with information on PD opportunities offered at the time, including advice from large branches of childcare providers. This process found that the majority of PD was regulatory focused, and that there was a gap in free PD for early childhood educators, targeting knowledge and skills to support children's health and wellbeing.

The scan also involved a review of capacity building, health promotion and workforce development approaches. Health promoting early childhood initiatives that had been offered over the past decade were reviewed to assist in identifying key learnings and successful components to inform the Healthy Kids model. This involved consultation with a sample of Queensland Government health promotion lead professionals and review of evidence-based, best practice health promoting frameworks that were identified and/or being applied by statewide government health promotion units, such as the health promoting schools framework,36 the platforms professional learning framework,37 and community capacity building framework approaches.38-40 This ensured a consultative health promotion approach was utilised and was founded in engaging and mobilising Queensland ECEC communities to improve the health and wellbeing of the children that they serve.

2.2 Stakeholder engagement phase—Establishment of strategic partnership group; ECEC sector engagement and consultation

The early phases of model development included reaching out to leaders in the ECEC field, and representatives from peak bodies within the sector, such as Department of Education and Training, The University of Southern Queensland, Early Childhood Australia, Health and Community Services Workforce Council, The C&K Association, Goodstart Early Learning, Lady Gowrie, and Inclusion Support Queensland. From these discussions, a cross-sector ECEC strategic partnership group was formed, the Healthy Kids Advisory Group, as an important mechanism to influence and drive model efficacy.

2.2.1 Establishment of advisory group

The Healthy Kids Advisory Group included 16 health and early education professionals from across government agencies, academics specialising in health and early childhood, and early childhood leaders. No specific qualifications were required for membership, however each attended bi-monthly Advisory Group meetings and provided ongoing advice. The group collectively recognised that face-to-face conversations were critical, that effective PD models encapsulated facilitated reflective practice as well as additional support between learning sessions (mentoring), and the benefit of focusing on an over-arching “theme” connecting several topics across the year. The group also identified that according to the 2015 AEDC results, Physical Health and Wellbeing, Social Competence and Emotional Maturity were the developmental domains that had highest levels of vulnerability in Queensland and that one of these should be the focus for the first year.

The Advisory Group examined existing frameworks for self-reflection and collaborated to create a template for small group reflective practice. Other factors recommended by the Advisory Group were that it would be beneficial to record the content, the timing of the sessions (critical to engage the right staff), and to link content to the ECEC NQS41 and Early Years Learning Framework.12 It was agreed that the purpose of Healthy Kids was: “to increase early childhood educators” capacity to address child health and development and enhance the health of children, families and ECEC staff'.

2.2.2 Engagement with the ECEC sector

As part of the engagement process, ECEC services located in the 10 identified communities, were invited to provide feedback on the model via an industry survey distributed by key stakeholders in November 2016. It is unknown how many ECEC services received the survey link however 201 surveys were returned by educators from long Daycare (51%), Family Daycare (31%), and Kindergarten (18%) services across all target communities in December 2016 and January 2017. The survey asked educators about their place of work, and preferred day, time, and topic of sessions to ensure the PD structure and content was relevant to the sector.

2.3 Design phase

The project team considered key recommendations from the Advisory Group, as well as survey feedback from educators. The resulting model was shared with the advisory group again for further feedback and suggested refinements. As can be seen in Tables 1 and 2, the first year of the Healthy Kids model comprised of an overarching theme, and four “events” that sat under this theme, one event for each school term.

| Theme: Social and emotional wellbeing | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event #1 early brain development | Event #2 supporting children to manage their emotions | Event #3 building relationships with children | Event #4 staff health and wellbeing | |||||||

| Jan | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

PD 1 Live webinar & Reflective practice |

PD 2 Live webinar & Reflective practice |

PD 3 Live webinar & Reflective practice |

PD 4 Live webinar & Reflective practice |

|||||||

| CHATs | CHATs | CHATs | CHATs | |||||||

| Newsletter | Newsletter | Newsletter | Newsletter | |||||||

| Delivery date | Themes | Number of communities | Number of attendees | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face-to-face | Online | Total | |||

| 2017 | Social and emotion wellbeing | ||||

| Feb | Early brain development | 10 | 294 | n/a | 294 |

| May | Supporting children to manage their emotions | 10 | 316 | n/a | 316 |

| Aug | Building relationships with children | 10 | 203 | n/a | 203 |

| Oct | Staff health and wellbeing | 12 | 275 | n/a | 275 |

| 1088 | |||||

| 2018 | Physical health and wellbeing | ||||

| Feb | Why movement is important for physical health and wellbeing | 15 | 430 | n/a | 430 |

| May | Physical building blocks in the early years | 14 | 299 | n/a | 299 |

| Aug | Creating environments to support active play | 14 | 277 | n/a | 277 |

| Oct | Growing good little eaters | 12 | 164 | n/a | 164 |

| 1170 | |||||

| 2019 | Language and communication | ||||

| Feb | Creating communication-friendly environments | 9 | 294 | n/a | 294 |

| May | Little ones love literacy | 10 | 160 | n/a | 160 |

| Aug | Communication and behaviour | 10 | 198 | n/a | 198 |

| Oct | Supporting bilingual children | 9 | 130 | n/a | 130 |

| 782 | |||||

| 2020 | Trauma-informed care in the early years | ||||

| Feb | Impact of early adversity and toxic stress on brain development | 14 | 538 | n/a | 538 |

| Remaining sessions cancelled due to COVID | 538 | ||||

| 2021 | Trauma-informed care in the early years | ||||

| Feb | Impact of early adversity and toxic stress on brain development | 14 | 278 | n/a | 278 |

| May | ACES and the impact of childhood trauma | 19 | 342 | n/a | 342 |

| Aug | Implicating a trauma-informed framework in early childhood | 9 | 90 | 119 | 231 |

| Oct | Managing the impact of others' trauma | 17 | 143 | n/a | 120 |

| 971 | |||||

| 2022 | Connecting with families and communities | ||||

| Feb | Understanding your families | 0 | n/a | 344 | 344 |

| May | Linking with your community | 8 | 97 | 127 | 224 |

| Aug | Partnering with families | 14 | 145 | 113 | 258 |

| Oct | Sensitive conversations with families | Yet to be delivered | |||

| TBC | |||||

Each event was made up of a PD session that included a webinar presentation by a “content expert”, followed by a small group reflective practice component. Events were held after hours in a community venue (eg, library, hall, university) in each of the 10 communities across Queensland. The following month a “Child Health Active Talk” (CHAT) was held, and follow-up e-newsletter was sent to subscribers. CCHW team members already working with the identified communities took on the coordinating and lead roles of running each PD session. After a PD session, CHATs provided a follow-up session to discuss and reflect on learnings from the PD and were considered best practice for translating knowledge into daily practice.23

2.4 Implementation and quality improvement phase—PDSA

The development of Healthy Kids, as well as the ongoing refinements of the model, evolved through quality improvement cycles using PDSA.42 The PDSA cycles drew on elements of participatory action research methodology to ensure early childhood staff participants informed ways to improve the model. The model was refined each quarter by asking participants and key stakeholders “how we can do better” at the conclusion of each session.43

Feedback was also captured on whether participants planned to try some of the strategies they had learnt, and how confident they felt to try something they had learnt or discussed at the Healthy Kids PD. This feedback was shared in the quarterly Healthy Kids newsletter postevent, and modifications were made to adapt to the needs of the ECEC communities. It provided an opportunity to build local communities of practice to reflect on information; share expertise and experiences and support each other in the practical application of tools and strategies. A summary of the quality improvement process and outcomes to establish the current model is provided in Table 3.

| Year | Quality improvement activities |

|---|---|

| 2017 |

|

| 2018 |

|

| 2019 |

|

| 2020 |

|

| 2021 |

|

| 2022 |

|

3 RESULTS

After several years of continuing to implement quality improvement cycles, the advisory group and the project team recognised that there were key components considered necessary for successful delivery. It was also recognised that flexibility was required to allow for community differences and to inject local contextual considerations. Results regarding current components of the Healthy Kids model are now discussed in more detail.

3.1 Components of the Healthy Kids model

3.1.1 Support crews

The project team worked with each community and the statewide partners to establish support crews for each community, responsible for the on-the-ground delivery of each event. The support crew membership and role has expanded over time, developing leadership and a higher level of community ownership in Healthy Kids. Support crew members included local champions in the early childhood sector, paediatric health practitioners and community organisations working in the early years. The project team provided annual training days for the support crews—developing their skills in facilitation, reflective practice, and key content areas.

3.1.2 Content delivery through webinars

Live webinars were initially utilised for these sessions, with each local ECEC community (ranging from 10 people in rural or remote areas up to 100 people in metropolitan areas), meeting face-to-face in one location and simultaneously linking into the delivery of the content presentation. A question-and-answer session with the presenter was conducted immediately after the webinar. At the designated time, each community joined the live presentation, and then at completion of the live webinar the facilitators would submit a question for the speaker. This presentation was recorded to allow for future use after the event.

The main pitfalls in using live webinars were difficulties experienced in both rural and remote communities accessing adequate internet speed and quality (as well as for the presenters themselves), or the ability for the presentation to be scheduled on an alternative date if required. To address these issues the decision was made to pre-record the content presentation. Communities generally chose to run their session simultaneously with other communities, confirming a preference for a statewide event. This provided a statewide “community” of educators, with some describing it as feeling as if they were part of something bigger than their individual early childhood service. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this presentation style continued to evolve with the trial of an online version to compliment the community-based sessions. The sudden and continuing impact of COVID-19 is described in Tables 2 and 3.

3.1.3 Reflective practice

Reflective practice supported ongoing professional learning by building on strengths and skills and providing a deeper understanding of how the latest information related to everyday roles and responsibilities. Within the early childhood section, both nationally (aligned with quality area 1)44 and more broadly, reflective practice is recognised as essential for driving continuous improvement. Genuine reflection also allows for a focussed attention on quality outcomes for children and families.24

The reflective practice element within Healthy Kids provided an opportunity for participants to discuss their learnings related to the health topic, in small groups. Within each reflection group, an identified support crew member facilitated discussion using a reflective practice template co-designed by the project team and Advisory Group. The reflection document was used as a prompt for the facilitator to lead the participants through their discussions.

The template breaks down the analysis of new and fresh information learnt during the presentation and applied it to the educator's daily practice. The reflections considered how new information related to existing knowledge and progresses to an action focus with educators identifying strategies that they would like to keep, stop, or start. This process of reflective practice supported services to meet the NQS and to improve the outcomes for children and families.

3.1.4 Local panel of early years professionals for question-and-answer (Q&A) session

Local health panels were introduced as part of the quality improvement process after feedback from attendees indicated that they did not have links with health professionals in their community. Educators reported they often spoke to parents about developmental concerns of children but did not know the right way to get help for families. Local health panels provided each group of early childhood educators an opportunity to meet and hear from the local health professionals and broader community support agencies in their own area.

Facilitated by the MC of the session, and run as a Q&A panel, educators asked questions related to the topic of the presentation, strategies to support children in their care, and the roles of health clinicians. The benefit was mutual as the health professionals used this opportunity to promote key developmental messages, explore appropriate strategies and explain local referral pathways. Invitations of local professionals to attend the events also helped to break down knowledge-based barriers, providing educators confidence to talk to families and make appropriate connections. The make-up of the panels has expanded over time, and now incorporates other local leaders in the early years.

3.1.5 Networking

During a Healthy Kids event both informal and formal networking occurred. Informal networking happened in the car park, before and after the event, and during breaks. Formal networking and professional conversations occurred during small group reflective practice. These times provided educators with the opportunity to share and receive knowledge, get fresh ideas, and build professional understanding. These social interactions afforded educators and other attendees space to build longer-term relationships, get to know who could provide support, and connect with others.

3.1.6 An electronic newsletter

To conclude each Healthy Kids event, subscribers were sent an electronic newsletter. This follow-up information related to the topic, contains the recorded webinar, handouts, relevant links, and resources. Where possible the newsletter show-cased examples of early childhood services implementing strategies learnt. The newsletter also promoted the next event in the series and reported feedback collected from the evaluation survey, including the most popular strategies that attendees wanted to implement at their service.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Key principles of the Healthy Kids model

A number of key principles have been identified by the project team after several iterations of the quality improvement process, recognising the critical factors that contribute to its successful delivery.

4.1.1 Low or no cost

The first principle identified was the importance of a model that was low or no cost to the participating communities and educators. Children in disadvantaged communities tend to benefit the most from quality early childhood education,16 however these areas often have centres less likely to meet NQS (particularly quality area 2), and commonly remote communities have limited access to training. A low or no cost initiative affords more populations the opportunity to access quality learning opportunities. Most costs of Healthy Kids were absorbed by the coordinating project team. These included the annual facilitator's training day, webinar production costs, stationery, and staffing resource to coordinate the delivery centrally. Presenters were sourced through Queensland Health, Department of Education and non-government organisations who provided their time at no cost.

4.1.2 Central coordination—Introducing the “Hub and Spoke”

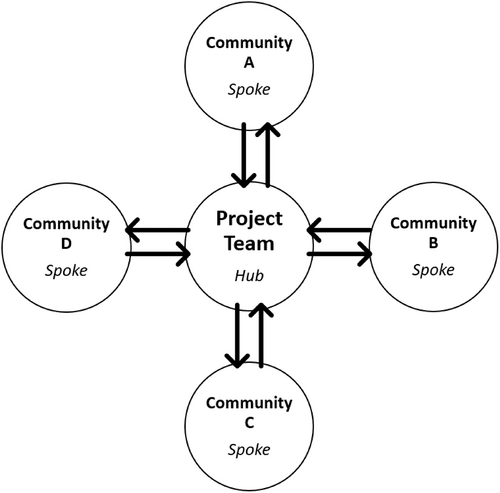

Integral to a range of health promotion models was the need for a coordinated team effort. This was achieved by implementing a “hub and spoke” approach (Figure 2), critical for keeping key components listed above consistent between communities, whilst allowing some tailoring based on an individual community's needs. The project team coordinator acted as the “hub,” and each community acted as a “spoke.” The hub-and-spoke approach was an important feature of Healthy Kids, given the diversity of each of the participating communities, in terms of size, geography, existing early years networks and community assets.

In the role of hub (Figure 2), the project team took on the responsibility of being the point of contact for the initiative, to source content and speakers, design and distribute promotional and learning materials, manage registrations, as well as publish the newsletter and support local delivery. In the role of spoke (See Figure 2), the support crew worked together to deliver the face-to-face event, utilizing the Healthy Kids content, materials, and structure, tailored for their community context. A “champion”, understood as someone who has taken ownership of the initiative in their area, acted as the main contact for the community. All members of the group collaborated to promote Healthy Kids, book and arrange the venue, set-up technology required, MC the event, facilitate small group reflective practice and contribute to the Q&A panel (see Table 4). A central hub allowed community support crews to deliver events more easily as the hub produced all resources required. It also provided a level of support for communities and workforces who may be less experienced in delivering PD for the early years sector.

| Project team responsibilities | Support crew responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Statewide coordination | Promote event to early years networks |

| Point of contact | Book and arrange the venue |

| Source content and speakers | Set-up technology |

| Design and distribute promotional material | MC event |

| Manage event registrations | Facilitate reflective practice |

| Support local delivery | Contribute to the Q&A panel |

| Host and MC online sessions | Facilitate breakout room in online session |

| Publish newsletter | Provide feedback |

| Evaluation |

4.1.3 Utilisation of community assets

Healthy Kids primarily relied on existing community assets to keep costs low. Community assets were understood within the broadest sense to include using established community or early years networks for promotion and support, sourcing of free-hire venues by participating organisations (eg, education site, libraries, council rooms, schools, and universities), shared printing and catering costs, and on the ground delivery and support included into people's usual roles. Utilisation of community assets reflected the valuing of others and their contexts and contributed to building the capacity of the support crew to deliver and facilitate events, whilst increasing the “local buy-in” and the long-term sustainability of the initiative. Program sustainability can be achieved through establishing a partnership for ongoing delivery of the program with decreased resourcing from the initiating agency.

4.1.4 Flexible and equitable delivery

Decisions made following the phases of planning mean that Healthy Kids was delivered in a flexible, equitable manner. Support was provided to ensure the education and training opportunities for educators in both metro and regional communities, who were already identified as experiencing vulnerability. This was achieved by employing strategies that allowed educators to access this PD without leaving their community and utilizing available technology. The flexible nature of Healthy Kids was further explored to adapt to the changing landscape as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic with online delivery options now included.

4.1.5 Meaningful topics

Topics were chosen based on feedback from a survey with educators where over 200 responses were analysed around preferred content based on the AEDC.9 The advisory group recommended that the PD should have one over-arching theme for each year, with quarterly events affording educators the opportunity for reflection and implementing change in their practice (Table 2). The inaugural priority theme identified was social and emotional wellbeing and specific sub-topics were chosen based on consultation with the advisory group and sector feedback. A key insight in the structure of events was beginning the sessions with theoretical underpinnings and progressing to practical strategies with opportunities for reflection during the presentation.

5 CONCLUSION

The goals of this initiative were to increase early childhood educators' capacity and knowledge of child health and development, support the integration of this knowledge into daily practice,44 and enhance the health and wellbeing of children and families they serve for low cost. As a result, an accessible, low-cost model was developed. Healthy Kids provides an opportunity to build local communities of practice to enable educators: to learn together and share expertise and experiences, to collaboratively develop and build knowledge and strategies, and to engage in reflection of practice. Healthy Kids includes six components and five key inter-related principles considered essential for building capacity through a workforce development strategy. The model promotes integrated partnerships across the early years period to better support children's health, development, and wellbeing. Research is currently being conducted to explore the efficacy of the model through examining the perceived value of regular attendance on early childhood knowledge, practice, and pedagogy.

The Healthy Kids health promotion model offers opportunities for transferability and contextualisation for others interested in building capacity across geographically diverse communities experiencing vulnerability. The components and principles of Healthy Kids offer a guide to assist in the consideration of designing and implementing similar health promotion initiatives. The authors of this paper encourage health, education, and social service sectors to step outside of their traditional boundaries and consider opportunities to work across settings to achieve a truly integrated, authentic, and meaningful approach to health promotion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our key stakeholders and early childhood leaders who contributed to the development of the Healthy Kids model through consultation, advisory groups, and support crew membership, and also to the educators who provided valuable feedback to help us develop a model that brings together the health and education sectors to build the capacity of early childhood educators to improve the outcome of Queensland kids. Open access publishing facilitated by University of Southern Queensland, as part of the Wiley - University of Southern Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was provided for this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.