Prevalence and characteristics of advocacy curricula in Australian public health degrees

Abstract

Background

Public health advocacy is a fundamental part of health promotion practice. Advocacy efforts can lead to healthier public policies and positive impacts on society. Public health educators are responsible for equipping graduates with cross-cutting advocacy competencies to address current and future public health challenges.

Problem

Knowledge of the extent to which students are taught public health advocacy is limited. To determine whether advocacy teaching within public health degrees matches industry needs, knowledge of pedagogical approaches to advocacy curricula is required. This study sought to understand the extent to which advocacy is taught and assessed within Australian public health degrees.

Methodology

Australian public health Bachelor's and Master's degrees were identified using the CRICOS database. Open-source online unit guides were reviewed to determine where and how advocacy was included within core and elective units (in title, unit description or learning outcomes). Degree directors and convenors of identified units were surveyed to further garner information about advocacy in the curriculum.

Results

Of 65 identified degrees, 17 of 26 (65%) undergraduate degrees and 24 of 39 (62%) postgraduate degrees included advocacy within the core curriculum, while 6 of 26 (23%) undergraduate and 8 of 39 (21%) postgraduate offered no advocacy curriculum.

Implications

Australian and international public health competency frameworks indicate advocacy curriculum should be included in all degrees. This research suggests advocacy competencies are not ubiquitous within Australian public health curricula. The findings support the need to advance public health advocacy teaching efforts further.

1 INTRODUCTION

Public health advocacy is a fundamental part of health promotion practice.1-3 Its importance is reflected by its inclusion as one of three pillars within the World Health Organization's Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion.3 The three pillars, “advocate,” “enable” and “mediate,” characterise the fundamental activities and competencies necessary to promote the health of populations.4, 5

Advocacy is the active support of a cause.6 It entails speaking, writing or acting in favour of a particular cause, policy or group of people.5 Public health advocacy efforts can take on many forms, employing a range of strategies that aim to influence and advance evidence-based policymaking to improve health and well-being for individuals and populations.5, 6 Advocacy can also raise awareness of social and environmental factors enabling systemic changes in these areas as well as mobilising communities. To achieve these outcomes, advocacy does not employ one consistent approach.6 Rather, activities and efforts can include a variety of strategies such as negotiation, debate and consensus generation in the pursuit of improved health and well-being.6 These advocacy activities can address the social and other determinants of health and lead to the development of healthier public policies and positive impacts on societies.6-8

The influence of public health advocacy has been demonstrated through several public health successes in Australia, including plain tobacco packaging, mandatory folate fortification within bread products and the ban on commercial tanning beds.9 Such successes were not made overnight. Advocates including health practitioners, policymakers and peak consumer advocacy bodies were required to coalesce and engage in extended and strategic efforts that ensured evidence was communicated in politically compelling ways, often in the face of fierce opposition from the commercial sector.6

Successful outcomes are achieved through a variety of strategies, including building the capacity of health professionals and building coalitions, although it has been described that some of the public health community may not feel comfortable or empowered to operate in this space.5

Importantly, recent global events such as COVID-19, which has flared vaccine hesitancy, and current issues such as climate change and the influence of major industries, have drawn attention to the critical need to develop an appropriately skilled public health workforce that engages with public health advocacy to meet current and emerging population health challenges.7, 10, 11 The Public Health Association of Australia states that a well-trained workforce is required, while emphasising the role of universities within this whole-of-system approach.8

In 2016, the peak organisation for public health education throughout Australasia, the Council of Academic Public Health Institutions Australasia (CAPHIA), proffered a foundational set of competencies expected from undergraduate and postgraduate public health students.12 The competencies recognise the role of public health advocacy in underpinning knowledge of health promotion and disease prevention12 and are consistent with the inclusion of advocacy in other international public health competency frameworks.13, 14 While public health undergraduates and postgraduates are expected to have knowledge and skills in public health advocacy,12 there is a paucity of literature on how it is taught to these cohorts.9, 11, 15, 16 Contributing to this is a dearth of empirical research on the practice of advocacy.17, 18 This may be due to the absence of a consensus on the definition of public health advocacy among academics, health practitioners and advocacy groups.1, 18 Despite accepted principals, no one consistent approach to advocacy exists.6, 18 While the discipline of advocacy enables a wide variety of practices to be implemented that are tailored for specific contexts,6 this can result in challenges in conducting research due to the varying heterogeneous methodologies. For the current study, the authors defined public health advocacy as educating, organising and mobilising for systems change in population health.19 While many definitions of public health advocacy exist, the authors selected this broad-spectrum definition as the foundation of this research to acknowledge the myriad of possible forms advocacy can take.

Because of the potential for advocacy to improve population health, previous research has called for a better understanding of advocacy in public health education.1, 18, 20 To determine whether advocacy curricula within Australian public health degrees match what is expected of graduates working in advocacy and health promotion roles once in the workforce, knowledge of advocacy curricula is required.

This study aims to determine the scope of public health advocacy education within undergraduate and postgraduate Australian public health degrees and whether advocacy education is delivered as part of the core curriculum, as part of electives, or not at all.

2 METHODS

2.1 Sample

To identify a list of Australian public health degrees, the Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students (CRICOS) database was used, applying the 0613 Public Health Field of Education.21 Bachelor- and Master-level degrees were included that related to the teaching of public/population health and variations of it, including global health, health policy, health communication and health promotion. Bachelor of Science or Bachelor of Health Science degrees where public health, population health or health promotion majors were offered were also included. This approach sought to provide a comprehensive list of recognised Australian institutions providing public health training.

Degrees related to health service management were excluded because these programs are typically more focused on organisational governance. Extended or Advanced degrees (eg Master of Public Health [Extension]) were excluded because they usually included the standard version of the same degree, with additional scope for electives. Degrees below an Australian Qualification Framework (AQF) Level 7 (sub-Bachelor level) were excluded. These were often abridged versions of Bachelor-level degrees, as were 1-year public health Honours degrees that are typically research-focused. For dual degrees, the base degree was counted once.

2.2 Data collection

Constructive alignment pedagogical theory22 was used as a guiding theory. Publicly available information for each included degree was manually extracted from the institution's online handbook and website by the researchers between July and August 2021. The nature and extent of advocacy within curricula were assessed, including whether “advoc*” was included in degree learning outcomes (DLOs). Attempts were made to contact the institution directly by two researchers (AB and SL). Where possible, the unit or degree coordinator listed was approached at least twice via email or phone. If such information was not available online, the researchers contacted the School/Department/Faculty or general university contact listed.

The AQF definition of an accredited unit was used.23 This definition states that an accredited unit is a single component of a qualification or stand-alone unit that has been accredited by the same process as for a whole AQF qualification; an accredited unit may be called a “module,” “subject,” “unit of competency” or “unit.”23

The authors identified all units offered within the degree (core and elective) that included “advoc*” in the unit title, unit description or unit level learning outcomes (ULOs) and extracted the data into Microsoft Excel. A single unit may be included as a core or elective across multiple degrees for some institutions. For example, a Foundation in Public Health unit may be included in both a Master of Public Health and Master of Global Health. In these cases, the unit was only counted once in the numerator. Similarly, there are cases where multiple units deliver advocacy teaching within the same degree. In these cases, the degree was only counted once in the denominator.

Previous research that used online handbook information to collect curriculum data recommended future studies draw from additional sources for more complete data.16 Considering this, and because some websites included limited details, where “advoc*” was identified in the unit title, description or ULOs, the unit convenor and degree director were invited via email to provide high-level details about the advocacy component of the relevant unit. This invitation included a Qualtrics link (Qualtrics, Provo, UT), a web-based survey platform. Additional data were collected from respondents, including the number of advocacy-specific learning outcomes and assessment details, such as type (eg, case study) and weighting. Unit convenors and degree directors received one reminder email 2 weeks after the initial invitation.

2.3 Data analysis

Additional data collected via surveys with unit convenors and degree directors were combined with data extracted from institutions' websites. A simple content analysis approach was used on extracted advocacy data to gauge how advocacy curricula were included within Australian tertiary public health education.16, 24, 25 Previous research shows that web-based content analysis is an appropriate method for auditing curricula content in public health degrees.16, 24 Denominators used to calculate proportions excluded degrees or units with missing data.

In this broad scoping exercise, a simple content analysis was conducted as follows. The authors looked for all mentions of “advoc*” in all core and elective unit titles, descriptions and learning outcomes. Proportions of degrees with “advoc*” in either a unit title, description or learning outcomes were calculated. Further, given that constructive alignment pedagogical theory would suggest that unit learning outcomes should be aligned to DLOs to maximise opportunities for student learning,22 the proportion of degrees that included “advoc*” in core unit learning outcomes alone was also calculated.

2.4 Ethics

The Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee approved this research (Ref. No. 520211009730240).

3 RESULTS

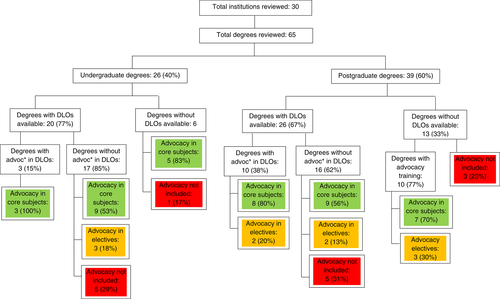

Using the CRICOS database, 175 eligible degrees (53 Bachelor's and 122 Master's) were identified. After exclusions, there were 65 degrees included for review from 30 Australian institutions: 26 undergraduate degrees and 39 postgraduate degrees (see Figure 1). Of the 65 degrees analysed, 41 (63%) included advocacy as part of core curricula; 14 (22%) did not include any identified advocacy curricula (Figure 1). DLOs could not be found online for 28 degrees.

3.1 Undergraduate

There was a total of 26 undergraduate degrees identified from 23 institutions. From these degrees, there were 39 relevant units identified: four from the unit title alone (10%), 21 from the learning outcomes (54%) and 14 from the unit description (36%).

Of the 26 degrees, 20 had DLOs publicly available; six degrees did not publicly report DLOs, and additional information could not be obtained from degree directors or institutions via attempts to contact these institutions made by researchers. Of the degrees with available DLOs, 3 out of 20 (15%) included “advoc*” in one DLO. No degree had more than one DLO mentioning “advoc*.” Each of these three degrees delivered advocacy training within core units. Of the 17 degrees which did not include “advoc*” in their DLOs, five did not include any units where “advoc*” was included as a learning outcome in the unit title or description. Notably, all five degrees were Bachelor of Health Science programs. For 12 degrees, while they did not include “advoc*” in their DLOs, they did include some advocacy training: nine degrees included it as part of the core curriculum, and three degrees included it as part of an elective option. For the six degrees that did not publicly report DLOs and attempts to determine this information from researchers was unsuccessful, five units included advocacy within the core curriculum, and one did not offer any advocacy curriculum.

In summary, six of the 26 degrees (23%) had no identified advocacy curriculum, and three (12%) only offered it as part of elective units, that is just 17 degrees (65%) had advocacy as part of the core curriculum. When only “advoc*” in unit learning outcomes are considered, 16 of 26 degrees (62%) included at least one core unit where “advoc*” was included in a learning outcome.

3.2 Postgraduate

A total of 39 postgraduate degrees were identified from 30 institutions. From these degrees, there were 55 relevant units identified: seven from the unit title alone (13%), 23 from the learning outcomes (42%), and 25 from the unit description (45%).

Of these degrees, 26 had DLOs publicly available or were obtained from degree directors; 13 degrees did not publicly report DLOs, and additional information could not be obtained from degree directors or institutions. Of the degrees with available DLOs, 10 out of 26 (38%) included “advoc*” in at least one DLO. Eight of these 10 degrees included advocacy training within at least one core unit; two degrees included advocacy training in electives. Of the 16 degrees without advocacy included in DLOs, nine included advocacy training in core units, two in electives only, and five had no identified advocacy training. For the 13 degrees where DLOs were not publicly reported, three degrees did not include any advocacy training. For the 10 degrees that did include advocacy training, seven units included it within core units and three degrees within elective units only. In summary, of the 39 identified postgraduate degrees, 31 included advocacy training (79%). Of these, 24 (62%) were delivered via core units.

In summary, eight of the 39 degrees (21%) had no identified advocacy training, and seven (18%) only offered it as part of elective units, that is just 24 degrees (62%) had advocacy as part of core training. When only “advoc*” in unit learning outcomes are considered, 13 of 39 degrees (50%) included at least one core unit where ‘advoc*' was included in a learning outcome, excluding the nine degrees where the unit learning outcomes were not available.

3.3 Assessments

Of the unit convenors and degree directors (N = 66) invited to complete the survey to supplement collected data, 34 responded (52% response rate). The majority of respondents provided additional detail regarding the type and weighting of assessment tasks which was used to supplement data collected from institutions' websites.

3.3.1 Undergraduate

Assessment details were obtained for 19 of 39 undergraduate units (49%). Five units did not include an advocacy-related assessment task. However, one of these units expressly included advocacy as part of one learning outcome. For the 19 units where assessment details were obtained, assessment of advocacy was very heterogenous: 4 of 19 (21%) were group assessments, 8 of 19 (42%) were short or long answer written assessments, and the rest were a mix of case studies, advocacy letter, online discussion or “other”, and weighting of assessment ranged from 10% to 50%.

3.3.2 Postgraduate

Assessment details were obtained for 22 of 55 postgraduate units (40%). Nine units did not include an advocacy-related assessment task. However, three of these units included advocacy as part of at least one learning outcome. For the remaining 13 units, all were individual tasks; five asked students to create an advocacy campaign/strategy, two were presentation tasks, and the others a mix of case studies, reflection, online discussion and an advocacy letter. Assessment weight was also varied between 5% and 50%.

4 DISCUSSION

This study provides an overview of the scope of public health advocacy education within Australian public health degrees. This audit indicates advocacy curricula are not ubiquitously delivered, with one-third of all identified degrees not including advocacy as part of core curricula and advocacy rarely included in DLOs.

These findings mirror the limited previous Australian-based research indicating public health advocacy receives minimal coverage in university curricula and the need to include public health advocacy training within core units.9 These gaps have also been reflected internationally,11 where there is also an identified lack of understanding of the optimal training format and length for teaching advocacy to other health disciplines (nurses)26 and medical students.20, 27

When a broad overview of advocacy training is considered (advocacy taught within core or elective units), it appears that advocacy is taught at a similar frequency in undergraduate (77%) and postgraduate degrees (79%). However, when considering good pedagogical practice requires essential learning to be expressly outlined in unit learning outcomes (where it is clear to students what they are learning) rather than only in unit descriptions, the difference between the qualification levels is starker. Although the frequency of advocacy within both undergraduate and postgraduate curricula is relatively low, this study found that 62% of undergraduate degrees included at least one core unit where advocacy was included in unit-level outcomes compared to only 50% of postgraduate degrees. The finding that this more frequently occurs in core undergraduate training may be due to the longer duration of undergraduate degrees, which allows an increased opportunity for the inclusion of advocacy training within the required curriculum.

It was identified that 14 (22%) of the eligible public health degrees do not include any advocacy training, raising issues with the advocacy capability of these degrees. However, it should be acknowledged that for many degrees, particularly postgraduate degrees, information on unit learning outcomes was not publicly available, and this figure may have been overestimated.

If advocacy is not routinely included within the core curriculum, as the findings indicate, but public health students are expected to graduate with advocacy competencies,12 there is a likelihood that some Australian public health graduates may not be adequately trained in advocacy. This has the potential to produce graduates who are not sufficiently prepared to deal with current and emerging population health challenges such as climate change and public health emergencies, which can stall health promotion advances that seek to improve the health and well-being of individuals and populations.

The highly varied inclusion of advocacy curricula across degrees suggests uneven alignment between advocacy competencies and DLOs, ULOs and advocacy-related assessment tasks. While universities have a responsibility to ensure public health students meet professional competencies,8, 27 at present, the graduate capabilities set out by CAPHIA are standards that institutions are encouraged to align to.12 These capabilities are not regulated due to the lack of requirement for accreditation in Australia, and not all institutions teaching public health curricula are CAPHIA members. This may partly explain why there is diversity in the inclusion of advocacy in Australian public health degrees. These findings demonstrate the need for public health programs within universities to comply with current standards so that students understand the nature of advocacy and the importance of advocacy in the policy process.

The low response rates from unit convenors and degree directors make it difficult for any meaningful inferences to be made regarding how advocacy is assessed. Attempts were made to supplement this with data extracted by researchers from institution websites. The diversity of assessment tasks used suggests that there are many ways to assess advocacy skills proficiency. However, further research is required to understand the type of advocacy skills needed in real-world advocacy practice and whether these skills are authentically assessed in units. A small number of units (n = 4, 4% of all units reviewed) reported advocacy as a learning outcome but did not assess it, which suggests there may be some poor alignment between learning outcomes and assessment in some degrees.

5 LIMITATIONS

Several limitations are noted in this study. Firstly, a conservative approach was taken to reviewing how advocacy was included within curricula with narrow search terms (“advoc*”). Additional search terms such as “community development/engagement”, “change” or “health communication” may have yielded more results. This method may have missed synonyms or concepts included in advocacy. A review of the unit learning outcomes of all health promotion, health policy and health communication units offered was carried out, but this did not yield additional data. Thus, there may have been some missed instances where advocacy skills are integrated into teaching but not explicitly mentioned and therefore not captured by this study. There might have also been some missed degrees if they were not registered on the CRICOS database. Future analysis could include a more comprehensive list of search terms or thematic identification.

A second limitation is that it was difficult to ascertain the exact extent to which advocacy was included within a unit. It was out of scope for the review team to audit the entire unit curricula, and it is possible that unit content was not fully aligned with the ULOs, unit title or description. Therefore, the audit did not investigate how much advocacy curricula are included or how well this is taught.

A third limitation is the currency of the information reviewed. This audit was completed between July and September 2021. Institutions regularly make amendments to the content offered within degrees, and advocacy offerings may have changed in some instances. Attempts to mitigate accuracy limitations were made by obtaining data from multiple sources, including online handbooks, institutions' websites, surveying unit convenors, and degree directors.16 Additionally, the audit was limited by the data made publicly available by each institution. While some institutions provided extensive and detailed information on their websites regarding degree and unit learning outcomes and assessment details, this information was wholly absent in the public domain for other institutions.

It is not clear what the effect of the combination of these limitations is. The prevalence's estimated here in this broad scoping review may be under or overestimated.

Finally, the researchers recognise their interest and involvement in teaching advocacy within their institution's public health degrees and that combined with the focus of this study, a desirability bias may be introduced.

6 CONCLUSION

This research provides an initial overview of how public health advocacy is included within Australian tertiary public health degrees. The researchers conclude that public health advocacy is not delivered consistently across degrees, and some students may miss out entirely. There remain opportunities to optimise advocacy curricula.

These findings highlight the need for Australian universities offering public health degrees to review and enhance their public health advocacy education offerings at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. A focus on ensuring advocacy is included within core units will allow students to graduate with foundational advocacy competencies set out by CAPHIA.12 In addition, it is important to ensure that where advocacy is taught and assessed, that this is explicit within the unit description and ULOs so that there is precise alignment with the foundational public health competencies, and it is clear to students what they are learning. Long-term university commitments to provide relevant advocacy training will contribute to investments in the public health workforce being adequately equipped to deal with emerging health issues such as climate change, public health emergencies and other issues that promote equity.

It is envisaged these findings will be particularly informative for degree directors, educators, and advocacy leaders seeking to augment public health advocacy training in the university sector. It is also envisaged that collaborative efforts at discipline-specific conferences such as CAPHIA learning and teaching forums could further facilitate work in this area.

Future research in this area should include determining the type of advocacy skills required for real-world advocacy practice, whether these skills are authentically assessed within public health training and best practice methods for training public health students in advocacy. The next steps for this research project include qualitative methods to assess pedagogical approaches to teaching advocacy via interviews with advocacy stakeholders to ensure teaching is optimally aligned to industry needs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The participation of degree directors and unit convenors who were surveyed about how advocacy was included in their degrees and units for the purposes of this audit is gratefully acknowledged. Open access publishing was facilitated by Macquarie University, as part of the Wiley - Macquarie University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no financial support for this research.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.