Appropriate and Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Decompensated Cirrhosis

Abstract

Background and Aims

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis are prescribed numerous medications. Data are limited as to whether patients are receiving medications they need and avoiding those they do not. We examined a large national claims database (2010-2015) to characterize the complete medication profile as well as the factors associated with appropriate and potentially inappropriate medication use in 12,621 patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Approach and Results

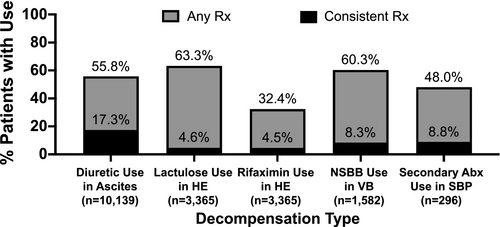

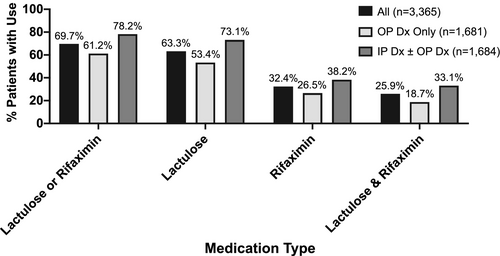

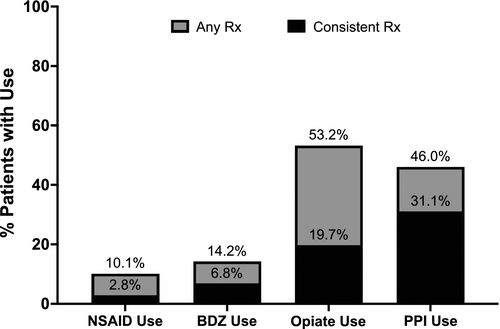

Clinical guidelines and existing literature were used to determine appropriate and potentially inappropriate medications in decompensated cirrhosis. The total medication days’ supply was calculated from pharmacy data and divided by the follow-up period for each decompensation. Ascites was the most common (86.5%), followed by hepatic encephalopathy (HE; 37.8%), variceal bleeding (VB; 17.5%), hepatorenal syndrome (6.3%), and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP; 6.1%). For patients with ascites, 55.8% filled a diuretic. For patients with HE, 32.4% and 63.3% filled rifaximin and lactulose, respectively. After VB, 60.3% of patients filled a nonselective beta blocker, and after an episode of SBP, 48.0% of patients filled an antibiotic for prophylaxis. The minority (4.5%-17.3%) had enough medication to cover >50% follow-up days. Potentially inappropriate medication use was common: 53.2% filled an opiate, 46.0% proton pump inhibitors, 14.2% benzodiazepines, and 10.1% nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Disease severity markers were associated with more appropriate mediation use but not consistently associated with less inappropriate medication use.

Conclusions

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis are not filling indicated medications as often or as long as is recommended and are also filling medications that are potentially harmful. Future steps include integrating pharmacy records with medical records to obtain a complete medication list and counseling on medication use with patients at each visit.

Abbreviations

-

- AKI

-

- acute kidney injury

-

- ALD

-

- alcohol-associated liver disease

-

- CHC

-

- chronic hepatitis C

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- ESRD

-

- end-stage renal disease

-

- HE

-

- hepatic encephalopathy

-

- HRS

-

- hepatorenal syndrome

-

- ICD-9

-

- International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- NAFLD

-

- nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

-

- NSAID

-

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

-

- NSBB

-

- nonselective beta blocker

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

-

- PPI

-

- proton pump inhibitor

-

- SBP

-

- spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

-

- TIPS

-

- transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis see multiple providers and are prescribed many medications. Several factors impact optimal medication management, including fractured care and inadequate medication reconciliation during clinic visits.(1) Even when used appropriately, the risk of adverse effects from indicated medications is real in this population wherein the therapeutic window for some medications is narrow.(2, 3) Medications indicated for decompensated cirrhosis include diuretics for ascites, lactulose and/or rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy (HE), nonselective beta blockers (NSBBs) after an episode of variceal bleeding or for large nonbleeding varices, and antibiotics for secondary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP).(4-7) Despite strong evidence in support of use of these medications, there are instances in which there are good reasons for a patient to not take one of these drugs. For example, a patient with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease could clinically deteriorate after starting an NSBB. Conversely, there are classes of medications that are more likely to cause harm among those with decompensated cirrhosis. These include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opiates, benzodiazepines, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).(8-15)

Studies of medication use in cirrhosis have largely been limited to studying one drug class with a specific type of decompensation.(16, 17) Patients with decompensated cirrhosis, however, often have more than one cirrhosis complication, and they frequently have comorbidities whose medical management is challenged by their cirrhosis. Accordingly, we evaluated complete medication profiles using pharmacy claims data to analyze appropriate and potentially inappropriate medication use in decompensated cirrhosis and identity factors associated with use.

Patients and Methods

Database

This is a retrospective cohort analysis of patients with decompensated cirrhosis and at least one outpatient pharmacy claim in the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart (Eden Prairie, MN). The Optum database consists of administrative health claims for a large national managed care organization covering 15-18 million lives in the United States. Commercial health plans with medication and prescription coverage as well as Medicare Advantage Part D plans are included. The database includes inpatient and outpatient International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes, Current Procedural Terminology codes (Supporting Table S1), provider type, and outpatient pharmacy claims information. Outpatient pharmacy claims information includes American Hospital Formulary System classification for dispensed medications and generic medication names as well as details of the quantity of drug dispensed, number of days’ supply, and cost. Pharmacy claims that were denied by insurance are not included in the database. Over-the-counter medications that patients take without a prescription are not included. Data are linked at the individual level, i.e., all outpatient visits, inpatient admissions, prescriptions, tests, and procedures that incurred an insurance claim are linked. However, the database does not include information found in the medical record, such as progress notes.

Population Sample

Decompensated cirrhosis was identified by the combination of an ICD-9 code for at least one cirrhosis complication (ascites, HE, variceal bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), and SBP, listed in Supporting Table S2) and an ICD-9 code for an etiology of cirrhosis (Supporting Table S3). The requirement that patients had an ICD-9 code for etiology of cirrhosis had a greater effect on decreasing the number of patients with coding for “Other Ascites” than other decompensation events and was done to increase the specificity for decompensation from liver disease. Because patients can have coexisting etiologies, priority was given to alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) or chronic hepatitis C (CHC)-related liver disease. Patients were considered to have ALD if they had at least one ICD-9 code for ALD or alcohol-associated end-organ damage, CHC-related cirrhosis if they had at least one ICD-9 code for CHC, or ALD/CHC if they had coding for both. Patients in these categories could also have coding for other etiologies of cirrhosis, such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). A non-ALD/non-CHC category captured the remaining patients without any coding for ALD and/or CHC. Patients in this category could have more than one etiology (e.g., NAFLD and chronic hepatitis B).

Follow-up periods started at each patient’s first episode of decompensation in the database (at or after 1/1/2010) until the end of continuous enrollment, liver transplant, death, or 9/30/2015, whichever occurred first. The date 9/30/2015 was chosen as the end of the follow-up period because this was when ICD-9 transitioned to ICD-10. Patients had at least 1 year of continuous enrollment before as well as after the date of their first liver decompensation. Those with a history of liver transplant before their first decompensation event or who underwent liver transplant or died within 90 days of their first decompensation were excluded. Finally, patients were required to have ICD-9 coding for an etiology of cirrhosis (Supporting Table S3) and to have filled at least one medication during their follow-up period (Supporting Fig. S1).

Appropriate Medication Use

Appropriate medication use in decompensated cirrhosis was based largely on American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines and quality measures (Supporting Table S4). Inappropriate medication use in decompensated cirrhosis can be more variable based on patient factors and was determined by clinical experience and reinforced by the existing literature (Supporting Table S5).

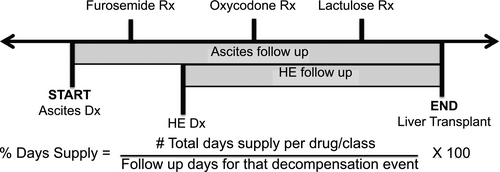

The proportion of patients with a specific cirrhosis complication who filled each class of medication was calculated. To calculate the proportion of follow-up time that the patient had a medication, the total days’ supply of a specific medication or medication class was calculated and divided by the follow-up period, starting with the first day of a specific complication (e.g., follow-up for lactulose period starting with first diagnosis code for HE; Fig. 1). Generic medication names or medication classes, sorted by appropriate or potentially inappropriate use, are listed in Supporting Tables S4 and S5. Consistent use was defined as having a supply of the medication for >50% of follow-up days for appropriate medications and ≥30 days’ supply per year for potentially inappropriate medications. Ascites and HE can be managed in the outpatient setting without requiring hospital admission. As such, diagnosis codes for ascites and HE were subdivided into those with only outpatient diagnosis codes (no inpatient codes) and those who had at least one inpatient diagnosis code. Notably, patients who had inpatient diagnosis codes could also have outpatient diagnoses of the same condition. ICD-9 codes were used to identify common comorbidities, and the codes used are listed in Supporting Table S6.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were presented as percentages for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical variables, and a Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine differences in medication days filled between two groups. Bivariate logistic regression was used to determine associations between patient factors/comorbidities and medication use. The results were reported as odds ratios (ORs). Stata was used for statistical analysis.(18) This study was exempted from review by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM00141255).

Results

Patient Population

The final cohort included 12,621 patients with decompensated cirrhosis (Fig. 2). Just over half of the cohort was male (56.3%), and the median age was 61 years. Almost two thirds (65.5%) were Caucasian and 14.8% were Hispanic. The patients were distributed through all four census regions, with the largest proportion (42.6%) coming from the South. Patients were followed for a median of 2.3 years (Table 1). Seventy-eight percent (77.9%) of patients saw a provider who specialized in gastroenterology or hepatology at least once during the follow-up period.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| n | 12,621 (%) |

| Sex (male) | 7,106 (56.3%) |

| Median age at first liver decompensation | 61 years (53-69) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 8,266 (65.5%) |

| African American | 1,150 (9.1%) |

| Asian | 342 (2.7%) |

| Unknown | 993 (7.9%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 1,870 (14.8%) |

| Census region | |

| South | 5,373 (42.6%) |

| West | 3,359 (26.6%) |

| Midwest | 2,272 (18.0%) |

| Northeast | 1,447 (11.5%) |

| Etiology of chronic liver disease | |

| ALD only | 4,842 (38.4%) |

| ALD and CHC | 1,884 (14.9%) |

| CHC only | 1,368 (10.8%) |

| Non-ALD/non-CHC* | 4,527 (35.9%) |

| NAFLD | 4,185 (92.5%) |

| Chronic hepatitis | 357 (7.9%) |

| Biliary cirrhosis | 307 (6.8%) |

| Hepatitis B | 166 (3.7%) |

| Presence of decompensation (≥1 may be present) | |

| Ascites | 10, 914 (86.5%) |

| HE | 4,776 (37.8%) |

| Variceal bleeding | 2,214 (17.5%) |

| HRS | 790 (6.3%) |

| SBP | 768 (6.1%) |

| Unique medications during follow-up | 9 (5-13) |

| Unique medications per year follow-up | 3.6 (1.8-6.8) |

| Median follow-up | 2.3 years (1.5-3.6 years) |

| Gastroenterology/hepatology consultation | 9,837 (77.9%) |

| Reason for ending follow-up | |

| Enrollment ended | 9,390 (74.4%) |

| Died | 2,603 (20.6%) |

| Underwent liver transplant | 628 (5.0%) |

Note:

- Data presented as n (%) or median (IQR).

- * Patient can have more than one etiology in the “Non-ALD/non-CHC” category breakdown.

Etiology of Liver Disease and Type of Decompensation

ALD was the most prevalent etiology (38.4%), followed by non-ALD/non-CHC at 35.9% (which largely consisted of patients with NAFLD), ALD with CHC (14.9%), and finally CHC only (10.8%). Ascites was the most common cirrhosis complication (86.5%), followed by HE (37.8%), variceal bleeding (17.5%), HRS (6.3%), and SBP (6.1%). Just over a third (36.4%) of patients had more than one type of decompensation. Patients took a median of 9 (IQR 5-13) unique medications during the entire follow-up period, and a median of 3.6 (IQR 1.8-6.8) unique medications per year of follow-up (Table 1).

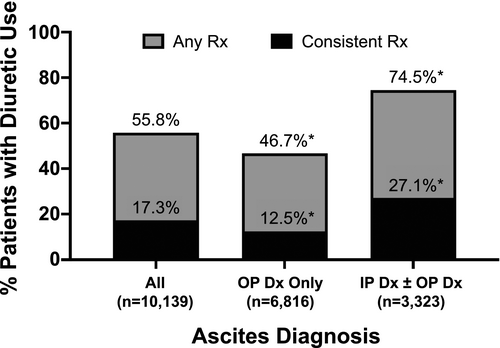

Appropriate Medication Use: Diuretics

Diuretics are recommended once a patient develops ascites (Supporting Table S4).(5, 19) Of the 10,139 patients with ICD-9 coding for ascites, 55.8% filled a prescription for a diuretic at least once during the follow-up period, but only 17.3% filled a prescription for diuretics consistently (>50% of follow-up period) (Figs. 2 and 3). One third (32.8%) of patients with ascites had at least one inpatient diagnosis code for ascites, and they had significantly higher rates of any diuretic use (74.5% vs. 46.7%, P < 0.001) and consistent diuretic use during follow-up (27.1% vs. 12.5%, P < 0.001) compared with those with only outpatient diagnoses of ascites (Fig. 2).

The presence of an inpatient diagnosis code for ascites (OR, 3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.0-3.6; P < 0.001) was found to be associated with any diuretic use. Subsequent requirement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.9-3.6; P < 0.001), a history of paracentesis (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.4-3.0; P < 0.001), and the number of paracenteses completed during follow-up (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.2-1.3; P < 0.001) were also associated with any diuretic use, as was male sex (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3-1.5; P < 0.001) and older age at time of first decompensation (OR per year, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.03-1.03; P < 0.001). Acute kidney injury (AKI) (OR, 2.4, 95% CI, 2.2-2.6; P < 0.001), chronic kidney disease (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 2.1-2.5; P < 0.001), and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.7-2.2; P < 0.001) were all associated with any diuretic use. Seeing a gastroenterology or hepatology provider was also associated with increased use of any diuretic (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.6-2.0; P < 0.001) (Table 2).

| Ascites | HE | Variceal Bleeding | SBP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 10,139 | n = 3,365 | n = 1,582 | n = 296 | ||

| Diuretic Use | Lactulose Use | Lactulose and Rifaximin Use | NSBB Use | Abx Use for Secondary PPx | |

| OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Sex (male) | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) P < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) P = 0.989 | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) P = 0.364 | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) P = 0.308 | 1.3 (0.8-2.1) P = 0.223 |

| Median age at first liver decompensation (year) | 1.03 (1.03-1.03) P < 0.001 | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) P < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.99-1.01) P = 0.791 | 0.99 (0.98-0.995) P = 0.003 | 1.0 (0.99-1.03) P = 0.422 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 1.2 (0.9-1.4) P = 0.156 | 0.8 (0.5-1.1) P = 0.210 | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) P = 0.575 | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) P = 0.672 | 0.8 (0.3-2.3) P = 0.659 |

| Hispanic | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) P = 0.277 | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) P = 0.603 | 1.3 (0.8-2.0) P = 0.267 | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) P = 0.712 | 0.7 (0.2-2.2) P = 0.526 |

| African American | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) P = 0.349 | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) P = 0.301 | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) P = 0.874 | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) P = 0.963 | 1.1 (0.3-4.0) P = 0.870 |

| Asian | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) P = 0.095 | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) P = 0.773 | 1.4 (0.7-2.7) P = 0.324 | 1.0 (0.5-2.3) P = 0.939 | 0.6 (0.1-4.6) P = 0.608 |

| Inpatient ascites diagnosis | 3.3 (3.0-3.6) P < 0.001 | 2.1 (1.3-3.6) P = 0.004 | |||

| Inpatient HE diagnosis | 2.4 (2.1-2.7) P < 0.001 | 2.1 (1.8-2.5) P < 0.001 | |||

| Rx before TIPS* | 2.7 (1.9-3.6) P < 0.001 | ||||

| Rx after TIPS† | 3.6 (1.8-7.2) P < 0.001 | 3.9 (2.4-6.4) P < 0.001 | |||

| Rx after paracentesis‡ | 2.7 (2.4-3.0) P < 0.001 | 1.5 (0.9-2.5) P = 0.095 | |||

| Paracentesis number during follow-up | 1.2 (1.2-1.3) P < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.995-1.1) P = 0.074 | |||

| Rx after EGD§ | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) P = 0.177 | ||||

| AKI | 2.4 (2.2-2.6) P < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) P = 0.807 | 1.7 (1.1-2.7) P = 0.029 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.3 (2.1-2.5) P < 0.001 | 0.8 (0.7-1.1) P = 0.170 | 1.3 (0.8-2.1) P = 0.312 | ||

| ESRD | 1.9 (1.7-2.2) P < 0.001 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) P = 0.168 | 1.9 (1.1-3.2) P = 0.023 | ||

| Bradycardia | 1.2 (0.96-1.5) P = 0.115 | ||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma | 0.7 (0.5-0.8) P < 0.001 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) P = 0.777 | ||||

| Gastroenterology or hepatology provider consultation | 1.8 (1.6-2.0) P < 0.001 | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) P < 0.001 | 2.4 (1.9-3.1) P < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.8-1.4) P = 0.852 | 2.2 (0.9-5.6) P = 0.086 |

- Values in bold are statistically significant.

- * Medication use before TIPS date for those who underwent TIPS compared with medication use for those who did not undergo TIPS.

- † Medication use after TIPS for those who underwent TIPS compared with medication use for those who did not undergo TIPS.

- ‡ Medication use after paracentesis compared with medication use for those who did not undergo paracentesis.

- § Medication use after EGD compared with medication use for those who did not undergo EGD.

- Abbreviations: Abx, antibiotic; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; PPx, prophylaxis; Rx, prescription.

Lactulose and/or Rifaximin

Lactulose is a first-line treatment after a patient develops overt HE,(6) whereas rifaximin is recommended after rehospitalization for HE (Supporting Table S4).(19) Of the 3,365 patients with HE, 69.7% were prescribed either lactulose or rifaximin, 63.3% lactulose, 32.4% rifaximin, and 25.9% both (Fig. 4). When each drug was evaluated individually, less than 5% of patients had enough supply of lactulose or rifaximin for consistent use (>50% of the follow-up period (Fig. 2)). Half (50.0%) of the patients with HE diagnoses had inpatient diagnosis codes for HE. An inpatient HE diagnosis was associated with higher rates of any lactulose use (73.1% vs. 53.4%, P < 0.001), any rifaximin use (38.2% vs. 26.5%, P < 0.001), and consistent rifaximin use (5.5% vs. 3.6%, P = 0.01).

Any lactulose use was associated with a history of TIPS (OR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.8-7.2; P < 0.001), an inpatient diagnosis of HE (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 2.1-2.7; P < 0.001), and older age at time of first decompensation (OR per year, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.02; P < 0.001). Dual lactulose and rifaximin use was associated with a history of a TIPS (OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 2.4-6.4; P < 0.001) and an inpatient diagnosis code of HE (OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.8-2.5; P < 0.001). Seeing a gastroenterology or hepatology provider was also associated with increased use of lactulose (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.7; P < 0.001) and concomitant lactulose and rifaximin use (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.9-3.1; P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Variceal Bleeding

NSBBs are recommended after an episode of variceal bleeding (Supporting Table S4).(7) Among 1,582 patients with an episode of variceal bleeding, just over half (60.3%) filled a prescription for an NSBB after the first episode, and only 8.3% filled this prescription consistently (Fig. 2). Having a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5-0.8; P < 0.001) and older age at the time of first decompensation was associated with lower likelihood of any NSBB use (OR per year, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-0.995; P = 0.003) (Table 2).

NSBBs may be dangerous in patients with ascites, SBP, or renal failure.(18) Patients with a history of variceal bleeding and ascites were more likely to have filled an NSBB (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.6; P = 0.02) compared with patients without concomitant ascites. No association with NSBB fill was seen in those with a history of variceal bleeding with SBP compared with those without SBP (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.9-1.9; P = 0.178) or those with variceal bleeding with HRS compared with those without HRS (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.6-1.2; P = 0.0424).

SBP

Patients with a history of SBP should be started on antibiotics to reduce risk of recurrence (Supporting Table S4).(5) Recommended antibiotics for this indication include ciprofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and norfloxacin. Half (48.0%) of the 296 patients with SBP filled a prescription for one of these antibiotics after the SBP diagnosis, but only 8.8% filled this prescription consistently (Fig. 2). An inpatient diagnosis of ascites (OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.3-3.6; P = 0.004) was associated with increased antibiotic use for secondary prophylaxis after SBP. AKI (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1-2.7; P = 0.029) and ESRD (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1-3.2; P = 0.023) were both associated with antibiotic use after SBP (Table 2).

Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use: NSAIDs

NSAIDs are generally felt to be unsafe in decompensated cirrhosis (Supporting Table S5).(8, 15) Roughly 10% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis filled prescriptions for NSAIDs during the follow-up period, and 2.8% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis filled these prescriptions consistently (≥30 days’ supply annually) (Fig. 5). Male sex (OR, 0.6; CI, 0.5-0.8; P < 0.001), an inpatient ascites diagnosis (OR, 0.7; CI, 0.6-0.8; P = 0.009), and having more paracenteses (OR, 0.9; CI, 0.9-0.97; P = 0.008) during follow-up were associated with less consistent NSAID use (Table 3).

| NSAID Use | Opiate Use | Benzodiazepine Use | PPI Use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Sex (male) | 0.6 (0.5-0.8) P < 0.001 | 0.9 (0.8-0.97) P = 0.006 | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) P < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) P = 0.667 |

| Age at first liver decompensation | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) P = 0.563 | 0.99 (0.98-0.99) P < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.97-0.98) P < 0.001 | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) P < 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) P = 0.972 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) P = 0.975 | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) P = 0.696 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) P = 0.838 |

| Hispanic | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) P = 0.629 | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) P = 0.094 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) P = 0.006 | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) P = 0.397 |

| African American | 1.2 (0.7-2.3) P = 0.511 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) P = 0.876 | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) P = 0.226 | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) P = 0.289 |

| Asian | 0.8 (0.3-2.0) P = 0.654 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) P < 0.001 | 0.5 (0.2-0.9) P = 0.023 | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) P = 0.317 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1.7 (1.6-1.9) P < 0.001 | |||

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 2.3 (2.1-2.5) P < 0.001 | |||

| Dyspepsia | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) P = 0.008 | |||

| Inpatient codes | ||||

| Inpatient ascites diagnosis | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) P = 0.009 | |||

| Inpatient HE diagnosis | 1.3 (1.2-1.5) P < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.8-1.1) P = 0.683 | ||

| Procedures | ||||

| Rx after TIPS* | 0.6 (0.3-0.98) P = 0.045 | 1.9 (0.7-5.8) P = 0.234 | ||

| Rx after paracentesis† | 0.8 (0.5-1.1) P = 0.141 | |||

| Paracentesis number during follow-up | 0.9 (0.8-0.97) P = 0.008 | |||

| Gastroenterology or hepatology provider consultation | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) P = 0.318 | 1.1 (0.99-1.2) P = 0.056 | 1.2 (0.99-1.4) P = 0.073 | 1.7 (1.5-1.8) P < 0.001 |

- Values in bold are statistically significant.

- * Medication use after TIPS for those who underwent TIPS compared with medication use for those who did not undergo TIPS.

- † Medication use after paracentesis compared with medication use for those who did not undergo paracentesis.

- Abbreviation: Rx, prescription.

Opiates and Benzodiazepines

Opiates and benzodiazepines should be used with caution in decompensated cirrhosis (Table 2). Alarmingly, over half the patients with decompensated cirrhosis (53.2%) filled a prescription for an opiate during follow-up, with almost a fifth filling them consistently (19.7%). Tramadol is classified as an opiate, and even so, the vast majority (91.1%) who filled an opiate prescription filled at least one nontramadol opiate. A smaller but still substantial percentage (14.2%) of patients filled a prescription for a benzodiazepine during the study follow-up, with 6.8% filling them consistently (Fig. 5).

An inpatient diagnosis of HE was associated with consistent opiate use (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.5; P < 0.001). Factors associated with less consistent opiate use included Asian race (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3-0.6; P < 0.001), history of TIPS (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-0.98; P = 0.045), male sex (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.8-0.97; P = 0.006), and older age at first decompensation (OR per year, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-0.99; P < 0.001). No factors were associated with more consistent benzodiazepine use. Factors associated with less consistent benzodiazepine use included Asian race (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.2-0.9; P = 0.023), Hispanic race (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-0.9; P = 0.006), male sex (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.6-0.8; P < 0.001), and older age at first decompensation (OR per year, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.97-0.98; P < 0.001) (Table 3).

PPIs

PPIs are commonly used but have the potential for harm in decompensated cirrhosis (Supporting Table S5). Not surprisingly, PPI use was prevalent in our cohort, with almost half (46.0%) of the patients taking PPI and nearly a third (31.1%) taking them consistently (Fig. 5). A diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease (OR, 2.3; CI, 2.1-2.5; P < 0.001), peptic ulcer disease (OR, 1.7; CI, 1.6-1.9; P < 0.001), and dyspepsia (OR, 1.2; CI, 1.1-1.4; P = 0.008) were associated with consistent PPI use, as was older age at the time of first decompensation (OR per year, 1.02; CI, 1.01-1.02; P < 0.001) (Table 3). Seeing a gastroenterology or hepatology provider was associated with more consistent PPI use (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.5-1.8; P < 0.001).

Discussion

Medications are the cornerstone of optimal care for persons with decompensated cirrhosis. Patterns of medication use therefore provide crucial data regarding the quality of care provided. We studied a large national sample of patients with cirrhosis and found that patients with decompensated cirrhosis are not regularly filling indicated medications, whereas many are routinely taking potentially dangerous medications. Furthermore, markers of cirrhosis severity were often, but not always, associated with appropriate medication use.

Gaps in Appropriate Use

Society guidelines and quality measures(5-7, 19, 20) provide clear recommendations of medications that should be prescribed to patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Our study showed that few patients are consistently taking recommended medications for their decompensated cirrhosis. Although 48.0%-63.3% of patients filled an indicated medication at least once, only 32.4% filled a prescription for rifaximin after an inpatient diagnosis of HE. Alarmingly, only 17.3% of patients with ascites had enough diuretic to cover at least 50% of follow-up days, and even fewer (4.5%-8.8%) had enough medication for consistent use for the other indications.

Markers of disease severity were often associated with appropriate medication use. Patients with ascites who had been hospitalized with this diagnosis were more likely to fill a prescription for diuretics for ascites and antibiotics for secondary prophylaxis of SBP. Patients with coding for renal impairment were more likely to be prescribed a diuretic; however, it is unclear if the renal impairment was secondary to diuretic use or a marker of the natural history of ascites progressing to refractory ascites. In addition, diuretics were more likely to be filled before TIPS placement in patients who eventually underwent this procedure compared with those who did not have TIPS, and patients who had a history of paracentesis were more likely to fill diuretics. Patients who had been hospitalized for HE were more likely to fill lactulose and rifaximin compared with those who only had been diagnosed with HE in the outpatient setting. Patients with HE and a history of TIPS were more likely to fill lactulose and rifaximin compared with those with HE who had not undergone TIPS. NSBB use after variceal bleeding was the only cohort that had consistent associations with medication nonuse. This may be related to comorbid conditions that may increase the risk of adverse events with NSBB use. Indeed, we found that older patients and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma were less likely to fill a NSBB after variceal bleeding.

During the follow-up period, evidence arose that NSBBs may be harmful in patients with refractory ascites, renal impairment, or SBP.(18) We found that, after an episode of variceal bleeding, patients with a history of ascites were more likely to have filled an NSBB than those with no ascites. A limitation of this data set is that we do not have data on blood pressure or renal function and are unable to confidently discern the severity of ascites (i.e., refractory ascites) to make firm conclusions whether NSBB use was appropriate or not. There was no association between NSBB fills after variceal bleeding for patients with a concomitant history of SBP or HRS. This finding may be related to concerns about NSBB use in these patients with more advanced cirrhosis.

The majority of patients in our cohort saw a gastroenterologist or hepatologist at least once. This consultation was associated with significantly more appropriate medication use in ascites and HE and a trend toward appropriate antibiotic use after an episode of SBP.

Potentially Inappropriate Use

A substantial proportion of patients with decompensated cirrhosis were taking potentially harmful medications, despite agreement among hepatologists that these are unsafe in decompensated cirrhosis (Supporting Table S5). Opiates are associated with hospital readmissions(11) and HE(12) in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, but over half of patients with decompensated cirrhosis filled at least one prescription for an opiate, and one fifth filled an opiate prescription consistently (≥30 days/annually). PPI use followed closely, with just under half of patients filling a prescription for one of these medications. Although the concerns about PPIs causing harm in cirrhosis are less direct,(13, 14) they are amplified given how prevalent PPI use is in this population. Approximately 15% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis filled at least one prescription for a benzodiazepine, a class of medication associated with similar risks(9) to opiates. NSAIDs clearly have the ability to harm patients with decompensated cirrhosis by precipitating renal failure(15) and gastrointestinal bleeding,(8) but still 10% of these patients filled a prescription for this class of medications. Notably, NSAID and PPI use are likely underestimated, as this database did not capture over-the-counter medication use.

Male sex was largely associated with less frequent use of potentially inappropriate medications, including NSAIDs, benzodiazepines, and opiates. Markers of liver disease severity had inconsistent associations with inappropriate medication use. For example, patients with ascites who received an inpatient diagnosis of ascites or had a history of paracentesis were less likely to consistently fill an NSAID, but patients with HE who had been hospitalized for HE were more likely to consistently fill an opiate.

There was no significant association between inappropriate medication use in decompensated cirrhosis and seeing a gastroenterologist or hepatologist, with the exception of increased use of PPIs. Patients with concomitant gastrointestinal problems may be more likely to see gastroenterologists and hepatologists, and this likely explains this finding.

Proposed Next Steps

Our data suggest that health care providers clearly do not know all the medications their patients take and how often they take these medications. Pharmacy records should be integrated with electronic health records to enable clinics and providers to have a list of not just medications prescribed but also all filled medications. This is key, as even highly educated patients have significant medication discrepancies when they are asked to compile their medication list.(22) Having not only a complete list of medications but also data on how often they are filled informs adherence and provides insight why some patients appear “not to respond” to appropriate treatment. Ideally, there is a multidisciplinary team that includes a pharmacist to assist with medication reconciliation in real time during clinic visits.(1) This information can then be used to counsel patients about the importance of consistently taking indicated medications and to discuss deprescribing potentially harmful medications. However, complete pharmacy and health record data will still not provide the full picture, as over-the-counter products, including NSAIDS, and health supplements will be missed.

In addition to gaps in our current health care system and our patients, provider knowledge deficiencies likely also contribute to suboptimal medication use. Future education efforts should include not just hepatologists and gastroenterologists but also other providers in primary care settings about recommended medications and potentially harmful medications in decompensated cirrhosis.

Contextual Factors

These data must be interpreted in the context of the study design. Our study included a large cohort (>12,000) of patients with decompensated cirrhosis, representative of the insured United States population spread across the country. Despite this, there are still populations excluded from the database (i.e., patients receiving all care at Veterans Affairs hospitals or other private insurers not participating in Optum). The database includes all medications patients actually filled from the pharmacy and prescriptions from all providers caring for a patient over several years. It also included all diagnosis and procedure codes billed to insurance during the study period, allowing us to determine whether the presence of comorbidities, such as asthma, accounted for NSBB nonuse and whether inpatient diagnosis of HE was associated with more frequent rifaximin use.

However, these data have multiple limits. First, we are unable to verify accuracy and completeness of ICD-9 coding, as patient level data were not available for review. Liver disease etiology was felt to be at highest risk for incomplete or inaccurate coding, so it was not used in analysis of factors associated with medication use. In fact, 64% of potentially eligible patients had to be excluded because of the lack of a diagnosis code for liver disease etiology, as we wanted to be certain that the included cohort had decompensated cirrhosis. The database only included laboratory data for a small subset; thus, severity of liver disease was based on diagnosis codes and whether those codes occurred as inpatient or outpatient.

Second, although a patient filling a prescription from a pharmacy is a more accurate measure of medication use than data based on prescriptions, it is still not a direct measure of what medications patients take day to day. For patients who present in person to pharmacies to pick up their refills, each refill likely represents consumption of the previous supply; however, for patients who get their refills through automated mail delivery, refills may not represent actual consumption. In addition, for medications such as diuretics or lactulose for which daily doses are frequently adjusted, the days’ supply may not reflect the amount needed.

Finally, as this database only reports medications that patients filled from a pharmacy, we are unable to determine if a medication was not filled (at all or consistently) because of a patient factor, insurance factor, or provider factor. We assumed that all patients with decompensated cirrhosis should be on medications recommended for cirrhosis complication(s) during the entire follow-up period, but there are often legitimate and illegitimate reasons why this may not be the case. Although we were able to examine some of these reasons and found explanations for not using recommended medications, e.g., fewer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma taking NSBB after a variceal bleed, the lack of granular information in the database did not allow us to determine whether there were legitimate reasons, such as resolution of cirrhosis complication, for not using or not consistently using medications in most patients. For example, a patient with ALD may have improvement in portal hypertension with sobriety and no longer requires diuretics. We expect scenarios like this to be the minority and that the majority of patients will require long-term medications to control or prevent recurrence of cirrhosis complications. Similarly, there may be legitimate reasons for use of some of the potentially inappropriate medications, such as PPIs or even opiates. Although one could argue that a short course of opiates is appropriate after a mechanical injury, particularly to avoid NSAIDs, having more than half of the patients with decompensated cirrhosis taking this class of medication and one fifth taking opiates consistently is concerning. We also could not determine if a medication was not filled because the patient chose to not fill it or was unable to fill it because it was not covered by insurance. We expect rifaximin fills to be affected most by the latter, as this medication is often prohibitively expensive or not covered by insurance.

Conclusions

In this large, nationally representative cohort study, we found that patients with decompensated cirrhosis are not filling indicated medications as often or for as long as is recommended per our society guidelines, even among patients who had been hospitalized for decompensation. In addition, patients are filling medications that are potentially harmful. Future steps to improve appropriate medication use in decompensated cirrhosis include integrating pharmacy records with the electronic health record to obtain a complete list of medications and dedicating time during each visit to counsel patients on the medications they should or should be not be taking, the purpose of each medication, their use, and possible side effects.

Author Contributions

All authors (M.J.T., A.S.F.L., E.B.T.) had substantial contributions to conception and design and analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published.