Massive hepatomegaly and involvement by Janus kinase 2–positive myeloproliferative neoplasm†

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

A 69-year-old woman presented with shortness of breath and remarkable hepatomegaly with extension into the pelvis (Fig. 1A). Past medical history revealed a 36-year history of polycythemia vera (PV) treated with splenectomy 12 years ago, and her medication included 3 g/day of hydroxyurea for the last 3 years. Aside from cardiopulmonary etiologies,1 in this setting, the differential diagnosis includes myeloid sarcoma, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and extensive extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH).

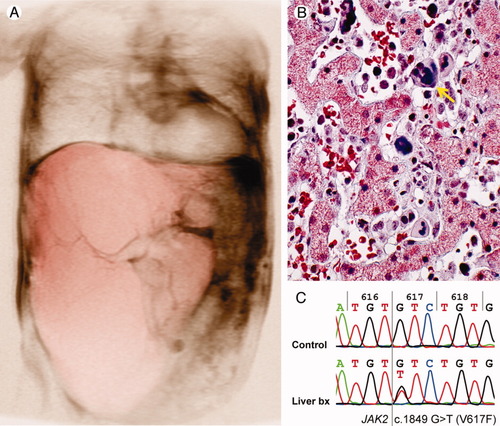

Liver involvement by JAK2+ myeloproliferative neoplasm. (A) Abdominal three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging reconstruction illustrates massive hepatomegaly extending into the pelvis (liver in pink; note the cardiomegaly). (B) Liver biopsy shows distended sinusoids filled with maturing hematopoietic elements of all three lineages, including large atypical megakaryocytes (arrow). There is no evidence of infiltrating blasts or overall effacement of the architecture. (Trichrome stain; magnification, ×400.) (C) Molecular analysis demonstrates heterozygous JAK2 point mutation with G→T transversion at nucleotide 1849, codon 617 (Control: commercial genomic DNA).

Abbreviations

EMH, extramedullary hematopoiesis; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; PV, polycythemia vera.

On admission, her white blood cell count was 75 × 106/L with 17% circulating blasts, platelet counts of 850 × 109/L, and a hematocrit of 0.35; teardrop erythrocytes as well as nucleated red blood cells were present. The alkaline phosphatase level was 1803 U/L (normal is <100 U/L). Workup showed absence of gastroesophageal varices or gastrointestinal bleeding, and ultrasound showed patent hepatic veins with markedly increased flow, a physiological condition incompatible with Budd-Chiari syndrome. Focal liver lesions were excluded by multimodal imaging; nonetheless, a liver biopsy was obtained to assess the possibility of leukemic infiltration. The needle core sample showed markedly distended sinusoids filled with hematopoietic elements without an increase in blasts (Fig. 1B). Extracted DNA from the liver showed a heterozygous JAK2 (Janus kinase 2) point mutation (Fig. 1C). These findings are diagnostic of involvement by the patient's known JAK2-positive myeloproliferative neoplasm rather than compensatory EMH or infiltration by blasts. The increased hepatic blood flow resulted in high-output heart failure with a cardiac index of 6.4 L/minute/m2 (normal is <4.2 L/minute/m2) and significant cardiomegaly (Fig. 1A) without evidence of pulmonary hypertension.1 The shortness of breath improved under diuretic and inotropic management but respiration was still limited by anatomic constraints imposed by the hepatomegaly.

The case demonstrates the remarkable sequelae of long-standing PV driven by 3 decades of constitutive cellular proliferation associated with activation of signaling downstream of the erythropoietin/thrombopoietin receptor (Val617Phe [V617F]-mediated loss of Jak homology 2 pseudokinase [JH2]-autoinhibition in JAK2). Liver enlargement to this extent is uncommon in myeloproliferative diseases and progressed markedly following her splenectomy. The liver findings after splenectomy also reflect the end stage of a hematopoietic shift from the biopsy-proven fibrotic medullary cavity to the liver, where the presence of the JAK2 mutation provides molecular evidence of a similar shift of the myeloproliferative clone to this site of embryonic hematopoiesis. Thereby, the findings combine components of existing theories of EMH discussed in the context of PV2 and myelofibrosis.3

Although a confirmatory bone marrow biopsy to demonstrate the requisite bone marrow fibrosis was not performed at the time of liver biopsy, based on the leukoerythroblastic blood smear, this disease is best classified as post-polycythemic myelofibrosis and the high numbers of circulating blasts over the last 8 years (up to 28%) formally meet diagnostic criteria of blast phase.4 However, the stable clinical course over almost a decade suggests that circulating JAK2-positive blasts may not necessarily be a poor prognostic indicator in PV.5 Given the stability of disease and absence of infiltration of the liver by blasts, the high number of circulating blasts may not represent acute leukemic transformation, but rather progenitor cell trafficking at their new site of hematopoiesis.6