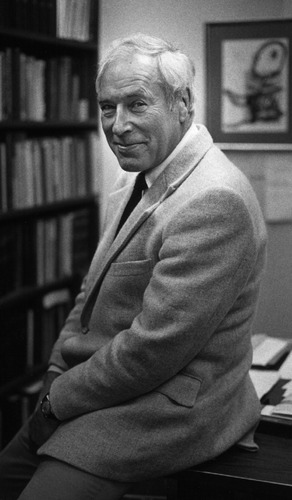

Rudi Schmid, M.D., Ph.D. (May 2, 1922–October 20, 2007)

Rudi Schmid was part of the small group who created the modern era of American hepatology. Born Swiss, he enjoyed relating the story of how he came to America and a career in academic gastroenterology. The history is worthy of Henry Fielding's Tom Jones, in which a young man with native intelligence, physical gifts, and charm finds success through a series of improbable events. Several versions exist. Ours was provided by Sonja Schmid, who was at his side for most of the story. She met Rudi at a traditional masked ball when he was a medical student on rotation in her home town of St. Gallen, which is high in the mountains of northeastern Switzerland, not far from Rudi's birthplace of Glarus. They married in 1949, in California.

Rudi Schmid

The story starts with Rudi's upbringing. Both parents were family physicians who expected their son to study medicine. He was indifferent to the idea but did become an expert skier and a member of the Swiss national team. He attended medical school at the University of Zürich but, by his own account, prioritized mountaineering, skiing, and girls in that order, with medical studies a distant fourth. He became president of the Academic Alpine Club, an elite group of climbers. Although he obtained his M.D., he failed to gain a residency position. Not being committed for further training, he joined a group for a 4-month trip to the Peruvian Andes. En route, with growing interest in the west, he wrote to a friend in San Francisco who was doing research with Karl F. Meyer, the famous bacteriologist at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), to inquire about internship possibilities. In Peru, the group made several first ascents. The final challenge was Alpamayo, a 19,500 ft. (6,000 m) pyramid of ice. Disaster struck as a cornice broke off, dropping Rudi and his tethered companions 600 feet and down a glacier. Amazingly, all survived and made it back to base camp.

In the meantime, the friend in San Francisco had given Rudi's name to K. F. Meyer, who was the lone Swiss at UCSF and a long-standing member of the same Alpine Club. Meyer spoke to Salvatore P. Lucia, a professor of Preventive Medicine who was looking for interns, telling him “Any president of this club has to be good!” Meanwhile, Rudi had developed an abscess over his sacrum that needed lancing. As it happened, the surgeon on duty was the son of the President of Peru. They hit it off, and Rudi accepted an invitation to attend a stag party for high-level dignitaries the same evening at the Presidential Palace in Lima. Not comfortable speaking Spanish, Rudi was happy to meet an American who was fluent in French. Conversation revealed that this man too was involved in medicine and in fact was none other than Salvatore P. Lucia (quelle surprise!), who had already written offering Rudi an internship at UCSF. Rudi accepted, although he lacked a visa. This final problem was resolved by going to the next room, where Lucia introduced him to the American ambassador. Two days later, the papers were ready.

Rudi had accepted the internship without really knowing what was involved. In San Francisco, with responsibility for patients' lives, he became a self-described hermit, reading voraciously in an effort to cover gaps in his medical knowledge and to improve his English. After several months, an opportunity arose to go skiing. However, when he wrote home for money, his father refused, seeing the trip only as a distraction. K. F. Meyer intervened, writing to the senior Schmid that Rudi was working hard and deserved a short holiday. Rudi left for Sun Valley after inviting Sonja to join him. As one of the best skiers on the mountain and apparently unattached, he attracted quite a following, which melted away after Sonja's arrival.

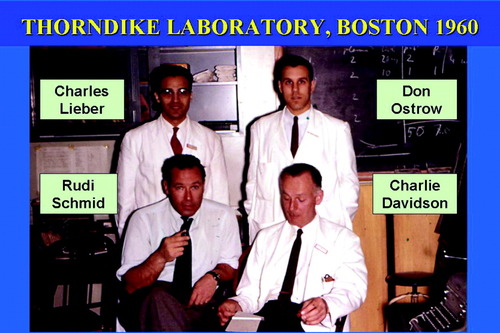

Rudi had no plan after finishing the year in San Francisco and was thinking of returning home. However, the man in charge of the resort was an old friend and teacher from Switzerland, who was locally well-connected. After a few telephone calls, Rudi had an offer of a medical residency and research training with Cecil J. Watson at the University of Minnesota. Watson, also a skier, had studied in Munich with Hans Fischer, a Nobel laureate in chemistry who had elucidated the structure of porphyrins. Rudi was given the task of creating an animal model of porphyria. He succeeded, presenting his data at the third meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) in 1952;1 he earned a Ph.D. in 1954. This launched his academic medical career, which, like his beloved downhill skiing, suited his competitive instincts, logical reasoning, and delight in risk-taking. After a few months in David Shemin's lab at Columbia University, he spent 2 years at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), proving that “direct-reacting” bilirubin was a glucuronide conjugate. His first faculty appointment was at Harvard's Thorndike Laboratory, Boston City Hospital (Fig. 1). From 1959-1962, he produced seminal papers on the formation, protein-binding, and intestinal and placental transport of [14C]-bilirubin (with Don Ostrow, Roger Lester, and Steve Schenker). The work continued at the University of Chicago, from 1962-1966, and included studies of kernicterus (with Ivan Diamond). In 1964-1965, he served as the 15th president of the AASLD.

The liver research group at Boston City Hospital, 1960. Rudi and Don Ostrow, his first research fellow, published the synthesis of [14C]bilirubin, from which followed numerous studies on the pigment's metabolism. Charles Lieber, although he was a fellow with Charlie Davidson, received important mentoring from Rudi. They were coauthors of Lieber's first publication, which examined the metabolic effects of alcohol on the liver. Rudi's pipe was a constant accessory until he developed oral leukoplakia in the mid-1970s.

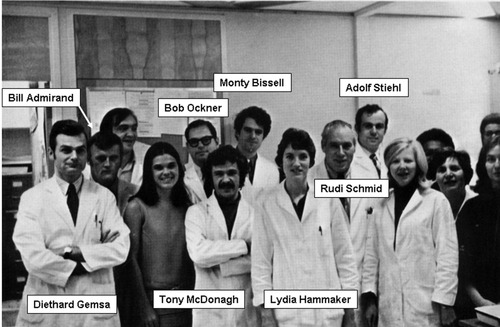

In 1966, Rudi was recruited back to San Francisco, charged with creating a modern Division of Gastroenterology. His Gastrointestinal Unit (Fig. 2) combined a strong, interdisciplinary research program with clinical training and became a model for other academic centers. In 1975, he founded UCSF's Liver Center, which, together with the Center at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, inaugurated the program of NIDDK-funded Digestive Disease Centers. His signal scientific achievement at UCSF was the first description of microsomal heme oxygenase as the activity that catalyzes the conversion of heme to bile pigment. Harvey Marver was a key collaborator in the initial studies. Tragically, he died in 1971 at age 37, of melanoma.2 In 1974, Rudi was elected to membership in the National Academy of Sciences.

The Gastrointestinal Unit at UCSF, 1972. Bob Ockner worked with Rudi as a medical student at the Thorndike. After a medical residency at Boston City Hospital, he joined the GI Unit as an Assistant Professor. Bill Admirand was an Assistant Professor with a focus on bile acid metabolism. Monty Bissell, Diethard Gemsa, and Adolf Stiehl were research fellows. Research Assistant Lydia Hammaker had joined Rudi's lab at the NIH, moving with him to Boston, Chicago, then San Francisco. Lydia ran the lab, trained fellows, and performed key experiments until her untimely death from colon cancer at age 50.

Rudi encouraged innovation while inculcating Swiss-style rigor in thinking, experimental design, execution, and writing. Draft manuscripts were deemed ready only when word-perfect. The myriad revisions required to achieve this mark were a source of frustration to trainees. Nonetheless the process drilled into them the principles of logical paragraph construction and clear syntax. There is no question that it accounted for the high proportion of manuscripts accepted by prestigious journals, often with no revision. Trainee preparation for oral presentations at scientific meetings was similarly rigorous.

Rudi's students were drawn by his charisma as much as by his success—this multicultural man with the conviction that any scientific challenge was surmountable by those with the appropriate mental toughness and ability to work. He had a passion for intellectual inquiry, whether scientific or secular. While enjoying a wine, he could maintain that red and white were indistinguishable to a blindfolded taster if both were served at the same temperature. His opponents argued that pipe smoking had destroyed his taste buds (Fig. 1). The question was never put to the test. Scientific debate often was heated, but when he was wrong, he would acknowledge the disputed point with “Goddammit, you were right!”, taking pleasure in having a fellow who was knowledgeable and capable of standing his or her ground. Rudi presided over a weekly Journal Club at which each trainee presented annually. The topic, chosen by Rudi, generally had no relation to the trainee's research area and required weeks of library preparation. The forum was decisive in determining one's academic future, testing not only the ability to organize and analyze information but also to think coolly under fire. To his graduates, he was fiercely loyal, supporting their careers and scientific endeavors long after they had moved on. Rudi trained a host of future leaders in hepatology. Eight became president of the AASLD (Steve Schenker, Bob Ockner, Don Ostrow, Roger Lester, John Gollan, Monty Bissell, Tom Boyer, and Teresa Wright). Another 20 became Division or Department chiefs in the United States or abroad.

In Rudi's universe, you led, followed, or got out of the way. He led, guided generally by his instincts, which usually were right. In 1983, he became Dean of the UCSF School of Medicine, a position he held for 6 years until mandatory retirement at age 67. He instituted major improvements in teaching programs which not only have survived but provided the foundation for recent curricular reforms and recognition of teaching excellence. He also remained deeply involved in hepatology. In 1983, he chaired a landmark NIH meeting on liver transplantation, which marked the start of the modern era of this procedure.3 In the latter stages of his career, he focused on building international programs, especially in China, where he was regarded as the father of Chinese academic hepatology.

With Rudi's passing, we celebrate a life well lived, characterized by passion and results. Although Rudi paid homage to Hans Popper for his role in initiating the field of hepatology,4 Rudi's own imprint is abundantly clear. We all owe much to this multilingual, Renaissance man for stimulating our minds, for instilling a love of science, and for teaching us to know the truth when we see it.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for contributions from Sonja Schmid and from several of Rudi's associates and colleagues.