Sequelae of carotid endarterectomy patch infection: An otolaryngologist perspective

Abstract

Background

Postoperative carotid endarterectomy (CEA) patch infection is a rare but well-recognized complication of CEA. It is important for otolaryngologists to be aware of the presentation and challenges in its diagnosis.

Methods

Patients who presented with a neck mass or hemorrhage and a known prior history of carotid endarterectomy with synthetic patch reconstruction were worked up with ultrasound, CT, or MRI imaging. In one case, fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed. Ultimately, all patients were taken to the operating room for neck exploration.

Results

Of the three patients presented in this case series, two presented with a chronic neck mass, two-to-three years after carotid endarterectomy. One patient presented acutely with hemorrhage from the carotid endarterectomy site. Carotid patch infection was diagnosed after neck exploration in all cases. Vascular surgery was consulted intra-operatively to perform definitive vascular repair.

Conclusions

Infected carotid patch should be suspected in patients with a history of prior CEA, as many of the presenting complaints may resemble or mimic pathology managed by otolaryngology. The onset of symptoms can be perioperative or very delayed. A multidisciplinary approach with vascular surgery and infectious disease is required for appropriate management of these patients.

1 INTRODUCTION

Carotid endarterectomy is a common operation performed to remove atherosclerotic plaque from the carotid artery and has been shown to decrease the risk of stroke in susceptible patients.1, 2 After making an arteriotomy, plaque is removed from the lumen and the artery is closed,3-5 often using a patch consisting of synthetic material (such as Dacron), bovine pericardium, or autogenous vein.6, 7 Postoperative patch infection is a rare but well-recognized complication of carotid endarterectomy in the vascular surgery literature.7-12 Synthetic patches carry a higher risk for infection than autogenous material,7, 8, 10 with Dacron patches having an infection rate of approximately 0.25%–0.50%.7 No particular material has been shown to be superior with regards to mortality, stroke, or restenosis outcomes.6 Patients with carotid patch infection may present acutely, or years after surgery, with patch rupture and hemorrhage, pseudoaneurysm, a chronic nonhealing wound, draining sinus tract, or neck swelling, mass, phlegmon, or abscess.10-12 Many of these symptoms can resemble or mimic pathology commonly encountered by an otolaryngologist. It therefore is important for otolaryngologists to be aware of the presentation of carotid patch infection and challenges in its diagnosis. In this series we present three cases of carotid patch infection presenting to our otolaryngology clinic and/or trauma center.

2 CASE #1

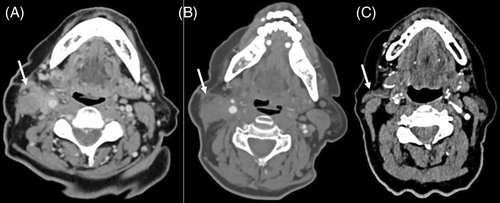

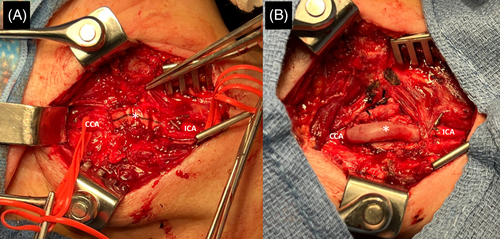

An 81-year-old woman presented to our clinic 3 years after right-sided carotid endarterectomy and Dacron patch closure with a right neck mass. She had a history of ipsilateral parotidectomy 30 years prior for pleomorphic adenoma. On examination there was a tender 3 × 4 cm neck mass at the upper aspect of the prior endarterectomy incision with a small scab immediately inferior to it. An MRI of the neck, completed 1 year prior, demonstrated a 1 × 2 × 2 cm area of abnormal enhancing tissue in the parotidectomy surgical bed and an ill-defined signal abnormality and enhancement along the medial margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The patient was referred for image guided tissue sampling. She had an episode of bleeding from the cervical skin breakdown site the night prior to the biopsy. The parotidectomy bed mass cytologic analysis revealed recurrent pleomorphic adenoma. There was no distinct area to biopsy in the neck. The patient was advised to come to emergency room should the bleeding recur. Two weeks later she had another episode of bleeding from the neck. An angiogram revealed no contrast extravasation. CT head and neck demonstrated enhancing infiltrative soft tissue along the right carotid artery, centered at the bifurcation, and extending along the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle towards the skin surface, concerning for infiltrative neoplasm. No rim-enhancing fluid collection was identified (Figure 1A,B). A fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed, revealing neutrophils consistent with an abscess. The decision was made to proceed with surgical exploration and possible incision and drainage. Vascular surgery was consulted preoperatively to be on stand-by. Once in the operating room, the mass was found to be pulsatile. Vascular surgery was called for an intraoperative consult. Intraoperatively, a fibrinous sinus tract draining purulent material was identified at the skin breakdown site and tracked down to a collection of scar tissue. Soft tissue specimens were sent for frozen pathology evaluation intraoperatively, which ruled out malignancy. Further exploration revealed a deeper sinus tract leading to an infected Dacron patch (Figure 2A). The patch was found to be dehiscent almost circumferentially. In the setting of the prior minor bleed event, patch dehiscence suggested that the patient was at risk for patch blowout with catastrophic bleeding. Explant of the infected Dacron carotid patch and a common carotid artery to internal carotid artery interposition bypass with great saphenous vein graft was performed by vascular surgery (Figure 2B). The external carotid artery was ligated. Tissue cultures collected intraoperatively did not grow any organisms. The patient was neurologically intact postoperatively. The patient was discharged on postoperative day #3 with a short course of oral antibiotics. The patient was seen in the clinic for follow-up 1 week after hospital discharge. Her neck incision appeared to be healing well at that time and she had no new complaints. Five months later, the patient returned to the clinic with complaint of persistent scab at the neck incision site and was found to have a stitch abscess that was incised and drained. Her postoperative course continued to be otherwise unremarkable. The patient continues to follow with vascular surgery for duplex ultrasound monitoring of the vascular reconstruction.

3 CASE #2

A 79-year-old woman presented to our clinic 3 years after right-sided carotid endarterectomy and Dacron patch closure with wound healing difficulty and a persistent draining sinus in the right neck. The patient had undergone two prior debridements of the non-healing neck wound, with excision of superficial granulation tissue, but the carotid patch had not been exposed as there was no suspicion for patch infection at that time. On examination, the patient had a draining sinus tract at the base of the right neck incision from which a sanguineous exudate without frank pus could be expressed. CT angiography demonstrated a widely patent right carotid artery and no evidence of abscess (Figure 1C). Treatment with daily Keflex was initiated until the patient could be taken to the operating room for exploration and debridement. Intraoperatively, extensive debridement was performed and the draining sinus tract was found to lead to the previous arteriotomy site. The Dacron patch was infected and a pseudoaneurysm of the internal carotid artery was identified distal to the patch. Explant of the infected carotid Dacron patch and a common carotid artery/external carotid artery to internal carotid artery interposition bypass with great saphenous vein graft was performed. For wound closure, a superiorly based sternocleidomastoid rotational flap was used to cover the defect area. Tissue cultures collected intraoperatively did not grow any organisms. The patient was discharged on postoperative day #6 with oral antibiotics. The patient was seen in the clinic 3 weeks after hospital discharge and had no signs of persistent infection. She will continue to follow with vascular surgery for duplex ultrasound monitoring of the vascular reconstruction.

4 CASE #3

A 71-year-old male presented emergently to our trauma center 1 month following left-sided carotid endarterectomy and bovine patch closure with concern for carotid blowout. The previous night, the patient had extensive bleeding from his neck incision that woke him from sleep. He presented to an outside hospital where a CT scan demonstrated concern for active hemorrhage from the left carotid endarterectomy site. The patient was intubated for airway protection with a pressure dressing applied to the left neck. He was transported via helicopter to our center for intervention. The patient was taken emergently to the operating room for control of carotid blowout and reconstruction. Intraoperatively, after dissecting down to the carotid artery patch, the surgical field was noted to be frankly infected. The necrotic and infected tissue was debrided. The carotid patch was removed in its entirety and a left common carotid artery to internal carotid artery interposition bypass with a 6 mm bovine graft was performed. The external carotid artery was ligated. Tissue cultures obtained intraoperatively grew pseudomonas aeruginosa. On postoperative day #10, the patient was taken back to the operating room for re-exploration and washout of the left neck incision due to concern for fluid collection on repeat CT angiography. A non-purulent seromatous fluid collection was identified and drained and gentamicin-infused antibiotic beads were placed in the surgical field. Repeat tissue culture produced no organisms. The patient was discharged on postoperative day #13 (day #3 after re-exploration) with oral antibiotics. He was seen in the clinic 6 weeks after hospital discharge and complained of new left neck pain and stiffness. A CTA head and neck demonstrated new stenosis of the reconstructed segment and the carotid artery bypass was stented by vascular surgery. The patient has been followed for 18 months since that time with unremarkable duplex ultrasound monitoring.

5 DISCUSSION

Patients with carotid patch infections may present with complaints mimicking those commonly seen by an otolaryngologist. However, to our knowledge, there are no reports of carotid patch infection in the otolaryngology literature. Risk factors for post-carotid endarterectomy infection include longer operative duration, additional procedures performed concurrently, and diabetes.13 Patients may report symptoms such as a chronic non-healing wound, drainage from the affected area, recurrent bleeding episodes or a neck mass, as seen in these cases. Although the incidence of patch infection is <1%, the potential morbidity and mortality is high.12 Despite its rarity, patch infection must be included on the differential diagnosis in patients who have a history of prior carotid endarterectomy, particularly if they are presenting with a neck mass. It is important to also include vascular surgery in the management of cases when carotid patch infection is suspected, as definitive management is likely to include total explant of the infected patch and vascular reconstruction to maintain cranial perfusion.7, 9

In the first case from this series, the patient had a neck mass concerning for malignancy. Given the history of prior parotidectomy, a recurrent salivary gland neoplasm was high on the differential, especially if supported by imaging. Once the fine needle aspiration biopsy of the neck mass returned contents consistent with abscess, it became apparent that an infectious etiology may be more likely. Additionally, new pulsatile nature of the mass alerted the Otolaryngologist to get the vascular surgery team involved at the very beginning of the case.

In the second case from this series, the patient presented initially with a chronic non-healing wound and draining sinus tract concerning for neck abscess. Patients who present with signs and symptoms that resemble soft tissue infection, but who have a history of ipsilateral carotid endarterectomy, should therefore be taken to the operating room for exploration. In this patient, prior surgical debridement failed to identify chronic carotid patch infection as only superficial tissue was explored. Only when the sinus tract was followed all the way to the prior arteriotomy site was it apparent that the carotid patch was the source of infection in this patient. A rotational muscle flap may be useful for closure of complex wounds after debridement and vascular reconstruction.

In the third case from this series, the patient presented shortly after carotid endarterectomy with sudden hemorrhage due to infection with a virulent organism and dehiscence of the patch. Sequelae of infected carotid patch may present soon after surgery, such an in this patient with a pseudomonal patch infection, but insidious presentation years after surgery is also common,7 and infection presenting up to 7 years after carotid endarterectomy has been reported.12 Late presentation of patch infection may be more likely to occur when less virulent organisms such as staphylococcus epidermidis are involved.7

Gram positive species, specifically staphylococcus aureus and staphylococcus epidermidis are the most commonly reported infectious organisms responsible for carotid patch infection in the literature.7, 9, 12 However, pseudomonal and bacteroides species have also been reported less commonly.7 Of note, one case series of 25 carotid patch infections found that one in five infections failed to grow any organisms on tissue culture, and so microbiology testing may not be reliable for diagnosis.12 It has been postulated that preoperative antibiotic use or infection with indolent organisms may lead to sterile cultures even when the carotid patch and surgical field are frankly infected.

The otolaryngologist's role in management of carotid patch infection may also include soft tissue reconstruction to protect the vascular repair. In one case from the present case series, a sternocleidomastoid flap was used to cover the defect. Sternocleidomastoid flaps and pectoralis major flaps have been described in the literature previously for this purpose.8, 9, 12

Infected carotid patch should be suspected in patients with a history of prior carotid endarterectomy, as many of the presenting complaints may resemble or mimic pathology managed by otolaryngology. A neck mass is a common presenting complaint for patients with carotid patch infection. The onset of symptoms can be perioperative or very delayed. Although the index of suspicion may be low given its rarity, carotid patch infection should be considered even 3 years or longer after carotid endarterectomy. Imaging with CT with contrast is useful in the initial evaluation. FNA should be performed if malignancy is on the differential. Ultimately, neck exploration will be required for confirmation of carotid patch infection as well as for intervention. A multidisciplinary approach with vascular surgery and infectious disease is required for appropriate management of these patients.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this case report are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical concerns, the data are not publicly available. Access to the data is subject to the approval of the institution's ethical review board and may require additional patient consent.