To educate a woman and to educate a man: Gender-specific sexual behavior and human immunodeficiency virus responses to an education reform in Botswana

Abstract

This study analyses mechanisms that link education to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with a focus on gender differences, using data from four nationally representative surveys in Botswana. To estimate the causal effect, an exogenous 1-year increase of junior secondary school is used. The key finding is that women and men responded differently to the reform. Among women, it led to delayed sexual debut and reduced time between first sex and marriage by up to a year. Among men, risky sex, measured by the likelihood of concurrent sexual partnerships and paying for sex, increased. The increase in risky sex among men is likely to be due to the education reform's positive impact on income. The reform reduced the likelihood of HIV infection sharply among women, especially among relatively young women age 18–24. The impact on men's likelihood of HIV infection is uncertain.

1 INTRODUCTION

HIV infections are decreasing in most countries, but still, about 730,000 individuals in Eastern and Southern Africa became infected in 2019 (UNAIDS, 2020). Since provision of antiretroviral treatment to a rapidly growing number of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive citizens is a major challenge, the international efforts to deal with HIV need to focus more strongly on prevention. As a result, increased schooling has received considerable attention and is being described as a powerful prevention method (UNAIDS, 2015a, 2015b; United Nations, 2016; World Bank, 2016).

In this paper, we analyze the links between education and HIV infection with an emphasis on gender differences. In both policy circles and the academic literature, the focus has been on the impact of education among women. Yet, according to theory, schooling may be linked to HIV through various channels with ambiguous aggregate effects, and these are likely to differ between women and men (Psaki, Chuang, Melnikas, Wilson, & Mensch, 2019). Studying gender differences in sexual behavior and HIV responses to schooling is important because the impact of education on men is of interest in itself and because they matter for HIV infections among both men and women, since men infect women and the other way around.

A simple model of sexual behavior guides the empirical analysis. One channel through which HIV is transmitted is adolescent sexual behavior. Increased schooling is predicted to affect adolescent sexual behavior because of the increased cost of pregnancy for women. Pregnancy is costly because it usually results in school dropout. Another channel of HIV transmission is adult sexual behavior. Increased schooling is predicted to increase income, which in turn affects the utility of transfers from sex partners. Since the transfers usually are from men to women, men might increase their demand for risky sex while women might reduce their supply. Increased income also makes children more affordable but it increases the opportunity cost of children for women. Thus, adult men are expected to increase risky sex due to the income effect, while the response of adult women is ambiguous.

To estimate casual effects, we use data from four nationally representative cross-sectional surveys, carried out in 2001, 2004, 2008 and 2013, and exploit an education reform in Botswana, a high-HIV-prevalence country. The education reform, implemented in 1996, shifted the 10th year of education from senior secondary to junior secondary school. Since a large share of students finish their schooling after junior secondary school (40% in our data), the reform constituted a dramatic increase in the number of students completing 10 years of education. The reform also included some curricula changes and a shift in the location at which students studied their 10th year.

Our identifying assumption is that nothing else affected children of relevant ages in 1996 in the same way as the education reform, that is, there was nothing else that affected only those who would start secondary school after the implementation of the reform and not those who had already started or finished secondary school. Thus, as Borkum (2010) and De Neve, Fink, Subramanian, Moyo, and Bor (2015), we assume that the education reform constituted an exogenous increase in the number of years of schooling.

While the identifying assumption cannot be directly tested, we run a number of placebo tests to evaluate its credibility. First, we test the impacts of earlier and later placebo reforms. As expected if the effects are due to the actual reform, the impacts of placebo reforms fade away as we move away from the actual reform year. Second, we test the impact of the reform on groups who should have been little affected by it; people who completed at most 8 years of education and people with at least some tertiary education. In general, the effects are in line with expectations.

Our work builds on De Neve et al. (2015), who found that the Botswana education reform reduced HIV infections. We first use the reform to estimate the impacts of secondary education on adolescent and adult sexual behavior for women and men, where adolescent sexual behavior is measured by age at first sex, and adult sexual behavior is measured by concurrency (having more than one simultaneous sexual relationship) and transactional sex (reception or payment of money or gifts in exchange for sex). Since income is likely to be an important channel for adult sexual behavior, we also estimate the impact on occupational skill level; we do not have data on income. Moreover, we estimate the impact on the likelihood of contracting an HIV infection. To understand our findings we then evaluate the impact of the education reform on women's total number of births, the time between sexual debut and marriage, age difference to the most recent sex partner, HIV knowledge, and age-specific infection risks.

The findings from the main analysis are as follows: The education reform delayed the sexual debut by about 7 months among women, while the impact among men is small. The education reform also led to better jobs for men, who were 8.9 percentage points more likely to have a skilled occupation, while the effect on women was positive but insignificant. Among men, there was an increase in concurrency by 7.4 percentage points and transactional sex by 2.7 percentage points, but no such changes were found among women. This impact on men's risky sexual behavior is most likely due to increased income along with the increased occupational skill levels. As for the overall impact of education on HIV incidence, the reform reduced HIV infection among women by 6.5 percentage points, while the estimated coefficient for men is small and insignificant.

The HIV effects on women are very similar to the reduced form impacts of the reform on HIV infection in De Neve et al. (2015). However, they also find a statistically significant reduction in HIV infection among men. The difference in their and our results for men is due to their inclusion of men who were younger than 10 years in 1996 in the estimation sample.

Our study contributes to the literature on the links between education and sexual behavior in developing countries. Several studies find a negative association between education and HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa (Hardee, Gay, Croce-Galis, and Peltz (2014). However, they do not provide information about the reasons for the correlation. Only a few studies employ strategies that aim to identify a causal effect of education on HIV, with varying results (Psaki et al., 2019). Among these, De Neve et al. (2015) provides the most convincing evidence of a casual effect, and it is the only study that includes both men and women. Using the Botswana education reform as an instrument, they find that 1 more year of secondary schooling reduced the risk of HIV infection among both women and men. However, they do not evaluate mechanisms that make education protective against HIV infection, and they do not focus on gender differences in the response to education. Among the other studies, Alsan and Cutler (2013) investigate age at first sex among women in Uganda but are forced to link age at first sex to HIV infections with model simulations due to lack of data. Agüero and Bharadwaj (2014) analyze and find an impact of education on Zimbabwean women's number of sex partners and HIV knowledge, but no statistically significant effect on HIV infections. And Durevall, Lindskog, and George (2019), who analyze current school attendance only, fail to find a causal effect among young women in South Africa. Thus, we lack studies that focus on gender differences and on mechanisms in a context where education is causally related to HIV infection.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESES

We investigate two specific links between education and HIV infection by gender: adolescent sexual behavior and adult sexual behavior. To this aim, we have developed a simple model to guide the empirical analysis Here we describe the model briefly. In Appendix I we describe it in more detail, relate it to earlier economic models of education and HIV transmission, and discuss empirical support of model assumptions.

Our model includes the most relevant aspects of previous models, with a focus on gender-specific hypotheses.1 Men and women engage in risky sex if the perceived marginal benefit of doing so exceeds the perceived marginal cost. However, the costs and benefits differ between the genders because women bear a higher cost of pregnancies, because the utility of risky sex could differ between the genders and because transfers involved are from men to women. There is ample support of such transfers from male to female sex partners in Southern and Eastern African countries (Tawfik & Watkins, 2007; Stobenau, 2016). Thus, risky sex yields direct utility and leads to transfers from men to women and increased probabilities of HIV infection and pregnancy. One potentially important simplification is that we consider only one type of risky sex.2

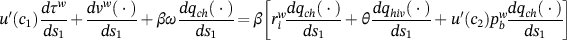

The model has two periods, adolescence and adulthood. We have derived first-order conditions (FOC) with respect to risky sex for each gender in each period, and use these to reason about the impacts of the exogenous education reform on optimal behavior. Below we briefly outline the FOCs and describe how they are affected by an increase in education.

(1)

(1) is marginal utility of the transfers from sex partners,

is marginal utility of the transfers from sex partners,  . Marginal utility of a given transfer is higher at a lower level of adolescent consumption,c1. In the second term, vw(⋅) is direct utility of risky sex, where the superscript w indicates that this might differ between women and men. The third term,

. Marginal utility of a given transfer is higher at a lower level of adolescent consumption,c1. In the second term, vw(⋅) is direct utility of risky sex, where the superscript w indicates that this might differ between women and men. The third term,  is the benefit of children if getting pregnant, where

is the benefit of children if getting pregnant, where  is the benefit of children and qch(⋅) the probability of pregnancy. This is discounted by the discount factor

is the benefit of children and qch(⋅) the probability of pregnancy. This is discounted by the discount factor  since benefits of children are assumed to occur in adulthood. All marginal cost terms on the right-hand side are discounted. The first,

since benefits of children are assumed to occur in adulthood. All marginal cost terms on the right-hand side are discounted. The first,  is lost returns to junior secondary education,

is lost returns to junior secondary education,  if the woman gets pregnant, since adolescent pregnancy leads to school drop-out, for which there is ample empirical support (Bandiera et al., 2017; Meekers & Ahmed, 1999). The second term is disutility of HIV infection where

if the woman gets pregnant, since adolescent pregnancy leads to school drop-out, for which there is ample empirical support (Bandiera et al., 2017; Meekers & Ahmed, 1999). The second term is disutility of HIV infection where  is the disutility and qhiv(⋅) the probability of infection. The last term is the cost of children if getting pregnant, where

is the disutility and qhiv(⋅) the probability of infection. The last term is the cost of children if getting pregnant, where  is the cost, which includes both financial and opportunity costs, and qch(⋅) is again the probability of pregnancy.

is the cost, which includes both financial and opportunity costs, and qch(⋅) is again the probability of pregnancy.There is no reason to believe that increased education affects the utility of risky sex and the cost of HIV infection. Moreover, since women who get pregnant drop out of school, and do not receive the increased return to education, the utility and cost of children that result from adolescence pregnancies is not affected by the increased education. However, the education reform increases the cost of school dropout,  since the return to completion of junior secondary school increases and young women are required to avoid pregnancy 1 more year to get the return. Assuming no costs of schooling, nothing else changes, and the unambiguous prediction is that adolescent women should reduce risky sex.

since the return to completion of junior secondary school increases and young women are required to avoid pregnancy 1 more year to get the return. Assuming no costs of schooling, nothing else changes, and the unambiguous prediction is that adolescent women should reduce risky sex.

If there is a cost of schooling in the form of lost income, the reduced level of consumption in adolescence, c1, when attending school 1 more year increases the utility of transfers from sex partners, creating an incentive to increase risky sex. The fact that almost everyone who can attend junior secondary school, that is, those who pass the primary school leaving examinations, do so (Borkum, 2010) suggests that returns to junior secondary school are (perceived to be) much higher than costs. Hence, if the probability that risky sex leads to pregnancy and school drop-out is perceived to be high, adolescent women would probably reduce risky sex. However, this depends on the exact probability of pregnancy, the difference between costs and expected returns of education, and the shape of the utility function.

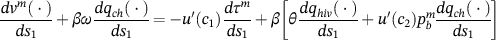

(2)

(2)It differ from women's FOC in that the transfer to sex partners,  is a cost and that they do not drop out of school if risky sex results in pregnancy. The cost of children,

is a cost and that they do not drop out of school if risky sex results in pregnancy. The cost of children,  only includes financial costs, that is, there are no opportunity costs of children. To the extent that men take financial responsibility of adolescent pregnancies, expected higher future income due to increased education and the resulting higher c2 decreases the utility loss from cost of children. If there are costs of education, such that c1 is reduced during the extra year of education, the utility loss of transfers to sex partners,

only includes financial costs, that is, there are no opportunity costs of children. To the extent that men take financial responsibility of adolescent pregnancies, expected higher future income due to increased education and the resulting higher c2 decreases the utility loss from cost of children. If there are costs of education, such that c1 is reduced during the extra year of education, the utility loss of transfers to sex partners,  increases. Since the two terms point in opposite direction (and we have no reason to believe that either is empirically strong), there is no clear prediction with regard to men's adolescent behavior.

increases. Since the two terms point in opposite direction (and we have no reason to believe that either is empirically strong), there is no clear prediction with regard to men's adolescent behavior.

(3)

(3)Increased education due to the reform increases returns to education and thereby income and c2 Borkum (2010) shows that incomes responded to the education reform in Botswana (wages increased by about 16% for men), which makes the link between education and HIV transmission that works through income relevant. The increased income has three effects among women: (i) it decreases the utility of transfers from sex partner, (ii) it makes the financial cost of children more affordable (the cost is lower in utility terms), and (iii) it increases the opportunity cost of children ( increase). This implies that one marginal benefit term,

increase). This implies that one marginal benefit term,  decreases (for given levels of risky sex) and one marginal cost term,

decreases (for given levels of risky sex) and one marginal cost term,  could be affected in either way. Thus, the net effect is uncertain.

could be affected in either way. Thus, the net effect is uncertain.

(4)

(4)As for women, the education reform increases income and hence c2. For men, this in turn reduces the cost (in utility terms) of transfers to sex partners,  , and makes the financial costs of children more affordable (

, and makes the financial costs of children more affordable ( is smaller). Hence, the unambiguous prediction from the model is that the reform should increase adult men's risky sex.

is smaller). Hence, the unambiguous prediction from the model is that the reform should increase adult men's risky sex.

While it is not clear whether adult women increase or decrease risky sex, adult men should increase it more than women. Some earlier empirical studies have also found a gender-differentiated sexual behavior response to income shocks in the region (Bryceson & Fonseca, 2006; Burke, Gong, & Jones, 2015; Kohler & Thornton, 2011).

2.1 Testing of specific hypotheses

In accordance with the model, we investigate adolescent and adult sexual behavior for women and for men. We test adolescent sexual behavior using information on age at first sex. This information was collected retrospectively for all participants in the first three survey rounds.

We consider two types of adult risky sex, which have been suggested as important drivers of the HIV epidemic: concurrent sexual relationships, here called concurrency, and receipt or payment of money or gifts in exchange for sex, that is, transactional sex. Concurrency has been suggested to be common in countries with high-HIV-prevalence, and to substantially increase the spread of HIV compared with serial monogamy, given the same total number of sex partners (Shelton, 2009). The reason is that concurrency increases the likelihood of having sex with someone else soon after being infected, when the viral load is particularly high. We measure concurrency using a binary variable that is equal to one if the respondents state that they currently have more than one sex partner.

Transactional sex has also been suggested to be common in high-HIV prevalence countries and to contribute to the spread of HIV through its connection to concurrency (Ranganathan et al., 2020; Stoebenau, Heise, Wamoyi, & Bobrova, 2016). We measure transactional sex using a binary variable that is equal to one if the respondents state that they have received or given gifts or money in exchange for sex. Since transactions are probably not that explicit in many transactional-sex relationships, we are not likely to capture all transactional sex with this variable. In particular, the explicit exchange of sex for money or gifts measured by this variable is a much narrower concept than the transfers from male to female sex partners in the model.

According to our theoretical framework, adult sexual behavior is affected mainly through the impact of education on a person's income. We do not observe income or wages in our data, but we do have detailed information on occupations. We therefore test whether the education reform affected the skill level of occupations.

3 THE EDUCATION REFORM

The education system in Botswana consists of 7 years of primary education and 5 years of secondary education. The five secondary years are divided into junior and senior secondary school. Before the reform, junior secondary school lasted 2 years and senior secondary school 3 years. A large share of students finish their schooling after the junior secondary school level (41.12% in our estimation sample). The reform shifted the 10th school year from senior to junior secondary school. Hence, the education system was reformed from a 7 + 2 + 3 year to a 7 + 3 + 2 year system. The policy affected students entering secondary school in 1996 or later, that is, those of age 15 or less on 1 January 1996.

In addition to an increased number of students attending the 10th year, there was a change in the location where students attend the 10th year and of the teachers who teach it. Yet, access to junior secondary school seems to have been unaffected by the policy reform, and due to the existing capacity, there does not seem to have been a decline in quality (Borkum, 2010).

The reform unavoidably involved some curricular changes, especially for the 10th year. In particular, there was an aim to make the curricula more relevant to the labor market. However, the effect of the curricular changes are likely to be of secondary importance compared with the additional year of study (Borkum, 2010).

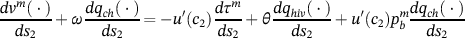

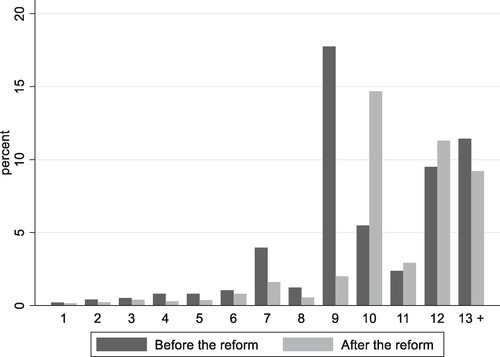

The education reform led to a substantial increase in the number of students completing 10 years of education. Figure 1 shows the shares who completed different grades before and after the reform. The before-reform shares are computed for people aged 16–20 in 1996 and the after-reform shares are computed for people aged 10–14 in 1996. There is a clear shift from completion of 9 grades to 10 grades. Figure 2 shows the shares who had completed at least 10 years of education by age in 1996. As evident, there is a shift toward completing grade 10 among people who were 15 years or younger in 1996.

Shares of respondents by gender who have completed different grades before and after the reform. Computed for people aged 20 or more at the time of the survey. Before-the-reform shares are computed for people aged 10–14 in 1996 and after–the-reform shares are computed for people aged 16–20 in 1996

Shares of respondents who have completed grade 10 by age in 1996 (with 95% confidence intervals). Shares and confidence intervals are computed for people aged 18 or more at the time of the survey

4 DATA AND EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

4.1 Data

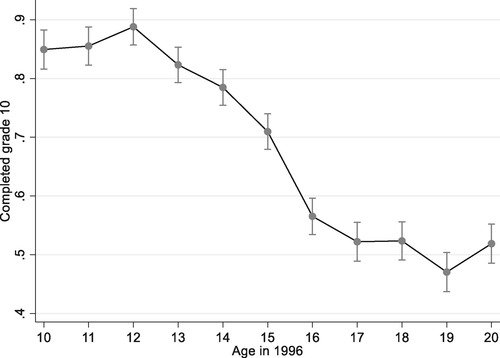

The Botswana AIDS Impact Surveys were carried out in 2001, 2004, 2008, and 2013. They are nationally representative cross-sectional surveys. The objective was to obtain information on the behavioral patterns of the population aged 10–64 years and the HIV prevalence at national and sub-national level. The data contain self-reported sexual behavior and HIV status based on blood samples. There is also information on socioeconomic factors such as education, occupation and labor market participation. Each survey consists of between 4500 (2001) and 14, 000 (2008) observations. Figure 3 shows the age distribution of the sample in 1996. As can be seen, the distribution is fairly uniform.3

Distribution of the estimation sample across age in 1996

Table 1 shows summary statistics by gender and survey for the dependent variables, and education and current age of respondents.4 Current age increases over the surveys, which is probably the main reason for changes in mean values across surveys. Age at first sex is about 18 years for both women and men. Men report more concurrency and transactional sex than women do. There is a large difference in HIV prevalence between the genders: about one-third of women are infected and about one-sixth of men. A large majority of individuals have some secondary education; while about one-sixth have only primary education and about one-sixth have some tertiary education.

| 2001 | 2004 | 2008 | 2013 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | N | ||

| Dependent variables | |||||||||||||

| Age at first sex | Women | 17.847 | 1.776 | 399 | 17.930 | 2.094 | 1570 | 18.601 | 2.474 | 2040 | |||

| Men | 17.373 | 2.071 | 300 | 17.612 | 2.730 | 1061 | 18.751 | 3.067 | 1528 | ||||

| Concurrency | Women | 0.055 | 0.229 | 1586 | 0.103 | 0.304 | 2152 | ||||||

| Men | 0.133 | 0.340 | 1263 | 0.239 | 0.426 | 1710 | |||||||

| Transactional sex | Women | 0.006 | 0. 076 | 343 | 0. 018 | 0. 134 | 1310 | 0.020 | 0.141 | 1879 | 0.011 | 0.104 | 1002 |

| Men | 0.022 | 0.147 | 271 | 0.022 | 0.145 | 929 | 0.027 | 0.161 | 1458 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 827 | |

| human immunodeficiency virus status | Women | 0.277 | 0.448 | 1730 | 0.332 | 0.471 | 1675 | 0.379 | 0.486 | 883 | |||

| Men | 0.109 | 0.312 | 1330 | 0.161 | 0.367 | 1270 | 0.214 | 0.410 | 748 | ||||

| Skilled occupation | Women | 0.638 | 0.482 | 141 | 0.695 | 0.461 | 594 | 0.752 | 0.432 | 943 | 0.658 | 0.474 | 855 |

| Men | 0.631 | 0.484 | 187 | 0.688 | 0.464 | 686 | 0.797 | 0.402 | 1113 | 0.791 | 0.407 | 996 | |

| Time (in years) between first sex and marriage | Women | 1.447 | 1.906 | 85 | 2.666 | 2.998 | 515 | 4.292 | 3.803 | 895 | |||

| Men | 2.688 | 2.967 | 32 | 3.583 | 3.201 | 216 | 5.402 | 4.250 | 507 | ||||

| Exposure | |||||||||||||

| Women | 0.323 | 0.428 | 507 | 0.522 | 0.477 | 1803 | 0.525 | 0.478 | 2640 | 0.537 | 0.485 | 1368 | |

| Men | 0.309 | 0.422 | 441 | 0.541 | 0.480 | 1388 | 0.522 | 0.475 | 2224 | 0.527 | 0.484 | 1238 | |

| Further description of the sample | |||||||||||||

| Age in years | Women | 21.247 | 2.263 | 507 | 22.735 | 3.134 | 1803 | 26.772 | 3.109 | 2640 | 31.530 | 3.122 | 1368 |

| Men | 21.313 | 2.255 | 441 | 22.620 | 3.224 | 1388 | 26.766 | 3.090 | 2224 | 31.595 | 3.122 | 1238 | |

| Never attended formal education | Women | 0.000 | 0.000 | 481 | 0.036 | 0.186 | 1803 | 0.042 | 0.201 | 2151 | 0.028 | 0.166 | 1129 |

| Men | 0.003 | 0.050 | 397 | 0.074 | 0.262 | 1387 | 0.077 | 0.267 | 1711 | 0.044 | 0.205 | 936 | |

| At least some primary education | Women | 0.108 | 0.311 | 481 | 0.098 | 0.298 | 1803 | 0.094 | 0.292 | 2151 | 0.087 | 0.282 | 1129 |

| Men | 0.181 | 0.386 | 397 | 0.125 | 0.331 | 1387 | 0.122 | 0.327 | 1711 | 0.123 | 0.328 | 936 | |

| At least some secondary education | Women | 0.848 | 0.359 | 481 | 0.748 | 0.434 | 1803 | 0.652 | 0.477 | 2151 | 0.620 | 0.486 | 1129 |

| Men | 0.720 | 0.449 | 397 | 0.640 | 0.480 | 1387 | 0.569 | 0.495 | 1711 | 0.509 | 0.500 | 936 | |

| At least some tertiary education | Women | 0.044 | 0.205 | 481 | 0.118 | 0.323 | 1803 | 0.212 | 0.408 | 2151 | 0.265 | 0.441 | 1129 |

| Men | 0.096 | 0.295 | 397 | 0.160 | 0.367 | 1387 | 0.233 | 0.423 | 1711 | 0.325 | 0.469 | 936 | |

| Years of education | Women | 9.860 | 2.135 | 480 | 10.441 | 2.392 | 1740 | 10.911 | 2.824 | 2083 | |||

| Men | 9.605 | 2.727 | 395 | 10.542 | 2.984 | 1289 | 10.969 | 3.324 | 1593 | ||||

Since there is no information on income in the surveys, we use International Labour Organization's International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) to classify the occupations into skill levels. A dummy variable that takes the value of one if a person belongs to one of the three highest skill groups in the labor market (professionals; technicians and associate professionals; legislators, administrators, and managers), and zero otherwise, was constructed. We also used the ISCO ranking for the nine main occupational categories as an alternative measure, and arrived at essentially the same results.5

4.2 Exposure probabilities

The school year in Botswana starts in January, and the calendar-year system is used to determine when a child should start first grade. An individual was exposed to the reform if he or she was eligible to enter secondary school in 1996 or later. We do not know with certainty whether each respondent was exposed to the reform or not for two reasons. First, as is typical in sub-Saharan African countries, many children are not in their age-appropriate grade in Botswana. Both delayed school entry and repetitions are common, and there are children who start school early. Hence, the relationship between age in 1996 (or birth year) and grade in 1996 is far from perfect. However, since the individual variation in grade in 1996 is endogenous, it is unsuitable for identification anyway. Instead, we use the variation in exposure to the reform that depends on the arguably external factor age in 1996.

. Then with probability pra96 the age at 1 January 1996 was the same as the age in 1996 at the date of the survey, and with probability 1−pra96 it was 1 year less than at the time of the survey. The exposure probability is then:

. Then with probability pra96 the age at 1 January 1996 was the same as the age in 1996 at the date of the survey, and with probability 1−pra96 it was 1 year less than at the time of the survey. The exposure probability is then:

(5)

(5)The fact that many children are not in their age-appropriate grade makes the measure of exposure an imprecise proxy of true exposure to the reform. As argued by La Ferrara and Milazzo (2017) this will bias our estimates downwards, making it harder to find effects. In robustness checks, we use an alternative exposure probability based on actual shares of children of different ages and gender who attended certain grades (Appendix IV provides details).

4.3 Identification strategy

The probabilities of exposure described by Equation (5) is our treatment variable. We thus estimate the impact of the education reform (the intent to treat, ITT) rather than the impact of an extra school year. We prefer reduced-form impacts of the reform instead of IV estimates of years of schooling for two reasons. First, although the most visible and important effect of the reform was that it substantially increased the number of students who attended a 10th year of education, this is not the only effect. By estimating the reduced form effect, we remain open to the possibility that part of the impact of the reform may be due to other factors than an increase in the number of years of education. Second, estimating the intent to treat has the additional advantage that we can use the fourth survey, collected in 2013, which does not contain information on years of education.

(6)

(6) are district dummies.

are district dummies.Our specification resembles, but is not, a regression-discontinuity design (RDD). It differs from an RDD since the exposure variable includes some probabilities between 0 and 1, and since we estimate the reduced form impact of the exposure.7 However, it is similar to an RDD, since the effect of the reform is identified from a discontinuity in the relationship between birth cohort and the outcome variable. It is also similar to an RDD, since the choice of how many birth cohorts to include in the estimation sample involves a trade-off between increased statistical power and the comparison of more similar people who were and were not exposed to the reform. In our main estimations we include people aged 10 to 20 in 1996. In our robustness analysis, we use the RDD bandwidth selection method developed by Cattaneo, Jansson, and Ma (2019).

Our identifying assumption is that nothing else happened that affected sexual behavior and HIV infections among people born in 1981 or later, but not people born before that. The age-in-1996 control and current age dummies are key to make that assumption credible. The main threat would probably be other changes in school affecting only those who had not started secondary school before 1996. As most high-HIV-prevalence countries, Botswana has introduced so-called life skills education, which includes HIV/AIDS knowledge, sex education and discussions about relationships. However, the policy was developed in 1998 and implemented after that, so it did not coincide with the education reform. A teacher-capacity training program was launched first in 2004. In fact, a general conclusion drawn by UNAIDS is that adolescents and young adults have been “largely neglected and left behind by the national HIV response” (UNAIDS, 2018).

Nevertheless, to further investigate the credibility of the identifying assumptions we run two types of placebo regressions. In the first set of regressions, we estimate the impact of “placebo reforms” occurring earlier or later than the actual reform. If estimated impacts are due to the reform they should fade away as we move further away from the actual reform year. In the second set of regressions, we test the impact of the reform on groups of people who should not be directly affected by it, that is,, those who completed at most 8 years of education and those who have at least some tertiary education.

4.4 Exposure to the reform among potential sex partners

People's sexual behavior does not depend on own intentions only but also on potential sex partners. The same is true for HIV infection. We estimate reduced form effects of the education reform, which include possible effects among potential sex partners. If potential sex partners are affected by the reform in a similar way as “treated” individuals, the impact of the education reform will be strengthened.

If we instead believe that women and men respond differently to the reform, there should be weaker effects. It could even be a challenge to identify gender differences. For example, if the reform increases men's sexual risk-taking, the impact might be muted if the reform has the opposite effect on their potential female sex partners. Similarly, if women are less interested in transactional sex for given levels of transfers, they may still not decrease transactional sex if men offer them larger transfers. While we have limited information on actual or potential sex partners, we do know the age of the most recent sex partner. This can be used to get an idea about the influence of opposite gender partners on our estimated overall effects.

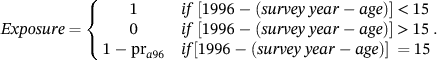

Figure 4 shows the average age difference between women and men of different ages and their most recent sex partner. A women's average sex partner is approximately 5 years older than she is, and this age difference is fairly stable across age. Men tend to have younger sex partners, but in contrast to women, the age difference increases gradually with age: for 18-year-old men the age difference is around −0.5 years, while it is almost −5 years for 33-year-old men. For the women in the estimation sample, this implies there is little variation in exposure status of potential partners; most of their partners were not exposed to the education reform. Hence, the estimated effect of increased schooling for the women is unlikely to be much influenced by a change in the behavior of their male sex partners. Among the men, exposure status of partners does to some extent vary with own exposure status. Men exposed to the reform will always tend to have women exposed, while unexposed men will have a mixture of women. This implies that the estimated effect of increased schooling for men is likely to be influenced by changed behavior of their partners, in particular when we estimate the impact on age at first sex, since the sexual debut is likely to have occurred at a relatively young age with a woman of similar age.

Average age difference between women and men and their most recent sex partner, by age. The figure shows the average age difference between women and their most recent male sex partner, and between men and their most recent female sex partner. The average age differences are displayed for each age

5 RESULTS

5.1 Main results

Table 2, reports the estimated impacts of being exposed to the reform on the age at first sex, concurrency, transactional sex, skilled occupation and HIV for women and men.8 The sexual behavior samples include only people who have had sex, and the skilled occupation sample only people reporting an occupation. We test the endogeneity of the estimation samples to the reform in Appendix II (Tables A1 and A2).

| Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First sex | Concurrency | Transactional sex | Skilled occupation | HIV | |

| Exposure | 0.626*** | −0.025 | 0.002 | 0.034 | −0.065** |

| (0.112) | (0.020) | (0.007) | (0.027) | (0.026) | |

| N | 4009 | 3738 | 4534 | 2533 | 4288 |

| Mean | 18.263 | 0.083 | 0.017 | 0.701 | 0.320 |

| Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First sex | Concurrency | Transactional sex | Skilled occupation | HIV | |

| Exposure | 0.017 | 0.074* | 0.027*** | 0.089*** | −0.021 |

| (0.189) | (0.039) | (0.005) | (0.025) | (0.018) | |

| N | 2889 | 2973 | 3485 | 2982 | 3348 |

| Mean | 18.189 | 0.194 | 0.023 | 0.760 | 0.152 |

- Notes: All regressions control for age in 1996 with a linear trend and have a full set of age dummies and district fixed effects. Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the birth year. Significance levels are indicated by * p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. Skilled occupation is a binary variable that is 1 for the three highest skill groups according to ILO's ISCO ranking.

- Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ILO, International Labour Organization; ISCO, International Standard Classification of Occupation.

Among women who had their sexual debut, there is strong evidence that the education reform delayed women's first sex by about 7 months: the estimate is significant at the 1% level.9 In contrast, the estimated coefficient for men is small and not statistically significant.

There is no indication that the reform affected concurrency and transactional sex among women; all coefficients are small, negative and statistically insignificant. Among men exposure to the reform increased the probability of having more than one partner by roughly 7 percentage points, while the probability of transactional sex increases by almost 3 percentage points.

The impact of the education reform on having a skilled occupation is positive but not statistically significant for women. For men, there is a statistically significant increase in the probability of a skilled occupation with almost 9 percentage points. Thus, the results for men are in line with an impact on adult sexual behavior through income.

The education reform reduced the probability to be HIV infected by 6 percentage among women. This can be compared with an average HIV infection rate of 32% in the estimation sample. The estimated effect on men's HIV infection is much smaller and not statistically significant.

A key finding this far is that the effects of the education reform appear to differ between women and men, so in the next step we test whether these differences are statistically significant. To do so we estimate fully interacted models, where a female dummy is interacted with all explanatory variables, on the pooled sample of men and women. Table 3 reports the interaction term between exposure to the reform and the female dummy.

| First sex | Concurrency | Transactional sex | Skilled occupation | HIV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female*Exposure | 0.609*** | −0.099** | −0.025** | −0.055 | −0.044 |

| (0.192) | (0.032) | (0.009) | (0.039) | (0.037) | |

| N | 6898 | 6711 | 8019 | 5515 | 7636 |

| Mean | 18.232 | 0.132 | 0.019 | 0.733 | 0.246 |

- Notes: All models are fully interacted. They control for age in 1996 with a linear trend and include a full set of age dummies, district fixed effects, a female dummy and interaction terms between the female dummy and all other variables. Only the interaction terms between the exposure measure and the female dummy are reported in the table. Significance levels are indicated by * p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

- Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Women seem to delay first sex more than men because of the reform. There is also a statistically significant difference in concurrency and transactional sex between women and men. Although the probability of having a skilled occupation increases more for men than for women, this difference is not statistically significant. Finally, while the estimates of the impact on HIV infection indicate a much larger effect on women than on men, the difference is not statistically significant.

5.2 Placebo checks

In our first set of placebo checks, we shift the timing of the reform back and forth in time. We first pretend that the reform occurred 3 years earlier than it actually did, that is, in 1993. We then estimate the impact of fictional reforms occurring 2 years earlier, one year earlier, 1 year later, 2 years later and 3 years later than the actual reform.10 For comparison, we also report the estimated impact of the actual reform. To avoid having a very small number of either exposed or unexposed individuals, we expand the sample window to include the 9–21 year olds. Figures A1–A5 in Appendix III show the results.

The expectation is to find the strongest effect at the time of the reform, and that the effect fades away as we move away from the reform year. This pattern is confirmed in all cases except for concurrency among men, for which the effects peak 1 year later. Nevertheless, even in this case the effects decline for fictional reform years further away from 1996. In general, fictional reforms are also less statistically significant as we move away from the actual reform year, but there are statistically significant coefficients of opposite sign at t−3 for men's concurrency.

Next, we run placebo checks where we estimate the impact on people who should not have been much affected by the reform; since there could be general equilibrium effects, we cannot say with certainty that any group is completely unaffected. People who completed grade 8 and less and those with at least some tertiary education are probably the least affected, since their school attainment ought to be unaffected. People who completed at most 8 years of education were clearly not induced to increase their schooling, and people with tertiary education would probably have gotten some tertiary education even without the reform.11 We added a control for belonging to the low-educated in these placebo regressions.12 Most effects are small and statistically insignificant (Table A3). The exception is the probability to have a skilled occupation among women: which decreased with 5.7 percentage points. This could be explained as a general equilibrium effect, but could also be pure chance.

5.3 Robustness checks

In our first set of robustness checks, we apply the regression discontinuity bandwidth selection method developed by Cattaneo et al. (2019). The highest age in 1996 is limited to 21, since older birth cohorts were exposed to an earlier education reform, and the lowest age in 1996 is limited to 6, for data availability reasons. We allow the sample window above age 15 in 1996 to differ from the one below age 15 in 1996. Tables A4 and A5 in Appendix IV report the estimated effects. The results are qualitatively similar to those in the main regressions. There are two noteworthy differences: First, the results for concurrency among men is somewhat weaker than in the main regression and the gender-difference in concurrency is therefore not statistically significant. Second, the difference in impact on HIV between women and men is statically significant.

Next, we add a squared term for age in 1996 (Table A6 and A7). Hence, we control for a continuous change in the outcomes over birth cohorts with both a linear and quadratic trend. Overall, the results are robust. The only differences compared to the main results are that the impact of the reform on men's concurrency and the gender difference in the impact on transactional sex are statistically stronger.

Next, along the lines of Borkum (2010) and Chicoine (2012) we use alternative exposure probabilities based on the actual shares of boys and girls of different ages in 1996 who had yet not started secondary school. The results are very similar to our main results, but effect sizes are consistently larger (Tables A8 and A9). This is what would be expected if these probabilities are closer to the true probabilities.

In our last robustness check, we estimate logit models for the binary outcomes. Tables A10 and A11 report the estimated marginal effects. Although the point estimates and significance levels differ somewhat, overall, the results are similar to those in the main analysis.

6 UNDERSTANDING THE FINDINGS

We find that women delay their sexual debut. According to the theoretical model, the desire to avoid pregnancies is a central motive behind adolescent women's sexual behavior. Our data includes the total number of births to women, but not the timing of these. Thus, we estimate the impact of the reform on women's total number of births, and, to shed some light on the timing of birth impacts, we split the sample into young women (age 18–24) and older women (age 25–32) (Table 4). The reform reduced the number of births by 0.129 children in the full sample. The next two columns suggest that this effect is entirely due to the younger women, who give birth to 0.279 fewer children. For the 26–32 year olds, the estimate is insignificant; among the older women, those who were exposed to the reform have given birth to as many children as those women who were not exposed. Hence, the reduction in total births among young women appears to be because of the timing of births, not because of a long-lasting reduction in the number of children.

| All | Age 18–25 | Age 26–32 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | −0.129** | −0.279*** | −0.028 |

| (0.056) | (0.068) | (0.079) | |

| N | 5327 | 2137 | 2764 |

| Mean | 1.370 | 0.734 | 1.702 |

- Notes: All regressions control for age in 1996 with a linear trend and have a full set of age dummies and district fixed effects. Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the birth year. Significance levels are indicated by *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

While women delay their sexual debut and give fewer births at young ages due to the reform, they do not change their adult risky sexual behavior as measured by transactional sex and concurrency. Yet, they are less likely to be HIV infected. This brings the question as to whether delayed sexual debut can explain the estimated decrease in HIV infections. According to a review by Stöckl, Kalra, Jacobi, and Watts (2013), there is some evidence that delayed sexual debut lowers HIV infection among women, but the effect size varies greatly across studies, and little is known about the mechanisms generating the association. However, one potentially important mechanism is the duration between first sex and marriage. Magruder (2011) develops a model and shows that this period, described as premarital partner search, is a key driver of the HIV epidemic in South Africa.

In Table 5, we report the impact of the education reform on the duration in years between first sex and marriage. Note that this is not defined for respondents who are not married, making the sample endogenous.13 Among women who were married at the time of the surveys, the education reform reduced the time between first sex and marriage by a year, while there was no impact among the men who were married by the time of the surveys.

| Time between first sex and marriage (in years) | Age-difference to last sex partner (age of partner minus own age) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Exposure | −1.034*** | 0.150 | −0.123 | −0.495** |

| (0.268) | (0.401) | (0.231) | (0.188) | |

| N | 1495 | 755 | 4945 | 3788 |

| Mean | 3.570 | 4.767 | 5.154 | −2.969 |

- Notes: All regressions control for age in 1996 with a linear trend and have a full set of age dummies and district fixed effects. Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the birth year. Significance levels are indicated by *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Thus, a shortened period of premarital partner search is one way in which delayed sexual debut reduces HIV infections. Another possibility is that the education reform reduced risky sex through sexual behaviors that we have not considered, for example, condom use, frequency of sex, and partner choice. We can analyze one aspect of partner choice, the age difference between partners. HIV infections increase by age, so younger partners are safer. The last two columns in Table 5 report the impact of the reform on the age difference to the most recent sexual partner. There is no impact among women, but a reduction among men by about half a year.

We can also evaluate another potentially important mediating factor of risky sex: improved knowledge. Agüero and Bharadwaj (2014) argue that increased secondary school attendance of black Zimbabwean women, due to the ending of apartheid, improved HIV knowledge and led to safer sexual behavior. To assess whether improved knowledge might have played a role also in Botswana, we analyzed the impact of the education reform on ten HIV knowledge indicators. The estimates (Tables A12-A13) vary across the indicators but most of them are not statistically significant. One reason is probably that knowledge about HIV was widespread in Botswana in the early 2000s (Botswana Government, 2009), as also indicated by the many mean values well over 80% in Tables A12–A13. Another possible reason for the lack of a positive impact is that we evaluate a 1-year increase in secondary education, while Agüero and Bharadwaj (2014) analyze a change from primary to secondary education.

If delayed sexual debut is the main reason for the reduction in HIV infections among women, there might be a limited long-run effect. Thus, if most women who would have been infected at a young age are infected later, the estimated impact of the education reform should differ depending on the woman's age. In Table 6, we report separate regressions on women and men aged 18–24 years and 25–32 years. The size of the estimated effect on women age 18–24 is 15 percentage points and highly significant. The estimates for the older women and men in both age groups are much smaller and not statistically significant. Clearly, the education reform prevented many young women from being infected. Unfortunately, we do not have data to evaluate thoroughly the dynamics of the epidemic caused by the delayed sexual debut.

| Women 18–24 | Women 25–32 | Men 18–24 | Men 25–32 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | −0.152*** | −0.023 | −0.018 | −0.024 |

| (0.017) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.018) | |

| N | 1674 | 2280 | 1269 | 1797 |

| Mean | 0.208 | 0.382 | 0.069 | 0.193 |

- Notes: All regressions control for age in 1996 with a linear trend and have a full set of age dummies and district fixed effects. Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the birth year. Significance levels are indicated by *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

- Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

We find that risky sexual behavior among men, measured by concurrency and transactional sex, increased, but we do not find an increase in HIV infections. This could be because condom use, partner choice and frequency of sex also changed. For example, we know that men exposed to the reform have younger partners (Table 5). In addition, men are likely to have benefitted from women's safer behavior and reduced HIV infections.

De Neve et al. (2015) found that the education reform reduced HIV infections for both men and women. Their reduced form effect for women is almost identical to ours, but for men it is larger (−0.05 rather than −0.02). Our estimations differ from De Neve et al. (2015) in two important ways: we have an additional survey, from 2013, and we do not include people who were 6–9 or 21 years in 1996 in our main estimation sample.14 We investigate why our results differ by first removing the 2013 survey from our sample, and then including respondents who were aged 6–9 or 21 in 1996 in the sample (Tables A14 and A15). The different results for men appear to be due to the inclusion of young birth cohorts in the estimation sample (not the 21 year olds15). When we include people, aged 6–9 or 21 in our sample, our estimates are very similar to their reduced form estimates, and there is a statistically significant reduction in HIV infections among men.

We have estimated reduced form effects of the reform rather than the impact on compliers who attended an extra year of education. Since some of our estimated impacts are surprisingly large compared to the means, particularly transactional sex among men, we investigate the impact of the reform on completed years of education. The effect of the reform could be large because it might have affected school attainment at other grades than the 10th year. In particular, a senior secondary school certificate could be obtained by studying two instead of 3 years after the reform. Table A15 reports estimates of the impact of the reform on completed years of education for women and men. The reform increases the years in school by about 1 year among women and just over half a year among men. The estimate is highly statistically significant for women, but only weakly so for men. If we use the same sample as De Neve et al., the estimated effects are close to their first-stage results: for women the effect is 0.87 and for men around 0.7, and both are statistically significant. Thus, the large effects of the reform on sexual behavior is probably to some extent due to a large effect of the reform on years in school. One should also bear in mind that the reform included other changes such as a changed curriculum and attendance of the 10th year closer to home. Curriculum changes might matter for impacts of the reform on income and the changed location of the 10th year might matter for the delayed sexual debut among women.

7 CONCLUSION

This paper uses an education reform in Botswana to analyze the link between education and sexual behavior and HIV infection among women and men, focusing on gender differences. The education reform increased school attainment from nine to 10 years for a large share of students and makes it possible to evaluate causal effects of increased schooling. We estimate the reduced form impact of the reform and find a difference in responses between women and men. Women delay their sexual debut by about 7 months, and reduce the time between sexual debut and marriage by about a year. They also reduce the number of births at young ages. The response among men with regard to age at first sex and duration of premarital sex is small and not statistically significant. Instead, men engage more in transactional sex (a 2.7 percentage point increase) and more often have concurrent relationships (a 7.4 percentage point increase), while there are no such responses among women. The differences in sexual behavior in response to education are in line with theoretical predictions from a simple model that focuses on differences in the costs and benefits of risky sex between women and men. Finally, the increase in schooling appears to be protective against HIV infection among women, particularly those below 25 years of age, while we do not find a protective effect among men. Based on the point estimates, the education reform reduced HIV infection on average by 6.4 percentage points among women, which can compared to a mean prevalence of about 32%.

Using different datasets, Borkum (2010) shows that the education reform improved wages and employment. His reduced form estimates indicate a 16% increase in wages for men and 22% increase for women, among those who have an occupation. We do not have data on wages but find that the education reform increased occupational skill levels for men, and possibly for women. Our results are therefore consistent with earlier studies showing that higher income increases men's risky sex (Burke et al., 2015; Kohler & Thornton, 2011; Robinson & Yeh, 2011). They are also in line with the theoretical model that suggest an impact on adult sexual behavior though increased income.

HIV infection does not only depend on own behavior but also on the behavior of sex partners. Women have partners who on average are 5 years older, implying that most of the partners of the women in our sample were not exposed to the education reform. While men tend to have younger partners, the age gap is small (0.5 years) for young men but then grows to 5–6 years for men around age 30. Hence, exposure to the education reform among sex partners varies more among men than among women. The correlation of exposure to the reform between men and their female partners is far from perfect, but men who were exposed to the reform tend to have female sex partners who also were exposed. This could be one explanation for why the impact of the reform on men's HIV infection is not positive in spite of their increased sexual risk behavior. Another reason could be that men reduce risk-taking in other ways. For example, while better-educated men seem to engage more in transactional sex and concurrency, they could also increase condom use.

Keeping girls in school is currently considered a powerful HIV prevention method in policy circles (UNAIDS, 2015a, 2015b; United Nations, 2016; World Bank, 2016) and academics (Remme, Vassall, Lutz, & Watts, 2012), and large investments have been devoted to this end (PEPFAR, 2016). The evidence from Botswana arguably supports this view. However, it also casts some doubt on the optimism of Remme, Watts, Heise, and Vassall (2015), who argue that investment in the expansion of secondary education could provide both education and an HIV-free future. Men and women infect each other, so if increased schooling increases sexual risk-taking among men, the positive effect on women might be reduced in the long run, particularly if delayed sexual debut is a main reason for the decline in HIV infections. On the other hand, focusing on the education of girls only might not be a defensible strategy in a context where young women are at least as educated as young men, which is now the case in Botswana and several other southern African countries. Thus, young men's education should be encouraged, but additional policies are needed. While we do not evaluate such additional policies, one potentially effective approach to alter the impact of education on sexual behavior and HIV is to implement or improve life skills education programs. Past experiences are disappointing, but a lot has been learnt and life skills education programs that use a genuinely educational approach to HIV and sex, while emphasizing gender, power and human rights, have shown some promise (Aggleton et al., 2018; Haberland & Rogow, 2015).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for funding from the Swedish Research Council. We are also grateful for comments and feedback from participants at the ASWEDE annual conference 2018, the 6th WCERE conference, the workshop on Public Health and Development in Gothenburg 2018, the IEB: IX Workshop on Economics of Education in Barcelona, and the South Africa - Sweden Research and Innovation Week 2019 in Stellenbosch. In particular we would like to thank the anonymous referees, James Fenske, Rohini Somanathan and Jorge Garcia-Hombrados for useful comments.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

ENDNOTES

- 1 We do not include mechanisms that ought to affect both genders equally.

- 2 We do not consider the difference between relationships with a high risk of HIV transmission and those with a high probability of pregnancy, since we are not able to distinguish empirically between the two types of sexual relationships.

- 3 We are unable to reject the null hypothesis of a continuous distribution of age in 1996 around the cutoff at the age of 15, using the manipulation test proposed by Cattaneo et al. (2019).

- 4 A Table showing the relationship between age in 1996 and current age across the years is available on request.

- 5 These results are available on request.

- 6 The first and second surveys were collected 12 February–31 July, the third 19 May–30 May and the fourth 22 January–22 April. We do not have the date of the interview for each individual and therefore use the day in the middle of the survey collection period for all respondents in a survey.

- 7 It is not a sharp regression-discontinuity design (RDD) since the reform only affected the probability to attain more years of schooling, and since we estimate the reduced form effect it is not a fuzzy RDD either.

- 8 The complete results are available from the authors on request.

- 9 Women have a reduced probability to report ever having had sex (Appendix II), so we might underestimate the reduction in risky sex among women. However, women are not less likely to report their age at first sex.

- 10 We do not test fictional reforms for four or more years before the actual reform to avoid the inclusion of birth cohorts that were exposed to a reform in 1988 that created the grade structure with 2 years of junior secondary school and 3 years senior secondary school.

- 11 This is in contrast to people who entered senior secondary school. The decision to enter senior secondary school entails two instead of three additional years after the reform. People with tertiary education have, however, been exposed to curricula changes and changed location of the 10th year of study.

- 12 We do not estimate separate regressions on either group due to the small sample sizes.

- 13 Regressions of the impact of the reform on the probability to be married show no impact on women but an increased probability to be married for men (not reported but available on request from the authors).

- 14 There are some other, minor, differences. First, De Neve et al. do not define the probability of exposure in the same way as we do. They assume that age at the beginning of the year is half a year less than current age. Second, we control for current district of residence while they control for district of birth for people who never moved and include people who ever moved in a separate group.

- 15 More detailed regressions are available on request.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available in article supplementary material.