Noninvasive Breast Cancer Screening Strategies Supported by AI-Based Technologies in Resource-Limited Settings: Is It the Best Opportunity to Strengthen Women's Preferences, Values and Acceptability?

Abbreviations

-

- AI

-

- artificial intelligence

-

- GLOBOCAN

-

- Global Cancer Observatory

-

- IHME

-

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

-

- WHO

-

- World Health Organization

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women globally, with its incidence continuing to rise, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, presenting a significant public health challenge worldwide [1]. According to data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and the World Health Organization (WHO), the gap in access to healthcare services between high- and low-income countries contributes to delayed detection, increased incidence of advanced-stage disease, and, consequently, higher mortality rates (up to 50% higher compared to high-income countries) [1, 2]. This translates into inequalities in access to screening and early diagnosis methods, which exacerbate the burden of this disease in low-resource settings where infrastructure, funding, and access to trained professionals are limited [3]. These limitations hinder the implementation of resource-dependent strategies required to achieve evidence-based outcomes, such as clinical breast exams (which necessitate trained personnel) or screening mammography (which requires appropriate infrastructure and trained specialists with adequate operator concordance) [4].

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) and emerging health technologies, particularly in the field of breast cancer screening, has shown to significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy and reduce operational costs in delivering comprehensive breast health services [5]. For instance, AI enables the development of low-cost imaging analysis systems, such as for mammograms and ultrasounds, that can be implemented in resource-limited settings [5]. Recent evidence suggests that these technologies can match or even exceed the diagnostic accuracy of radiologists in detecting suspicious lesions, a critical advancement in regions facing a shortage of these professionals [6].

A common limitation in low- and middle-income countries is the presence of cultural and social barriers, often related to the preferences, values, and needs of women [7]. In ancestral, conservative, and vulnerable communities, there is a notable level of mistrust and resistance toward certain interventions, primarily when these do not account for factors that benefit their communities [7]. Integrating women's values and preferences is essential for the success of any public health program. Previous research has indicated that women in these communities prefer noninvasive methods that reduce pain and minimize the risk of unnecessary radiation exposure [7]. AI-based technologies can personalize the screening experience, making it less invasive and more aligned with patient needs, thereby enhancing acceptability and adherence [5]. This approach can help overcome barriers such as language, physical exposure, direct palpation, among others, which strengthens trust and demonstrates the added value of safeguarding these women's health [5].

For AI-based technologies to reach their full potential in early detection within low-resource settings, planning is needed that includes training healthcare professionals, ensuring the economic sustainability of programs, and developing appropriate infrastructure [8]. Health systems must prioritize the accessibility of these devices and AI algorithms, optimizing their application in remote areas with limited, practical options for screening and early diagnosis [8].

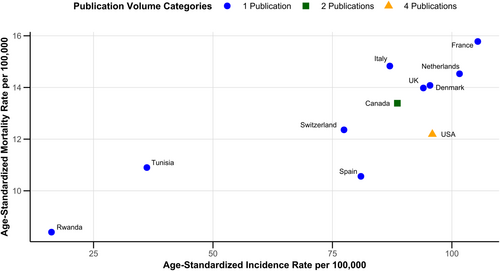

To illustrate the current knowledge and population gaps in the availability of primary evidence on women's preferences, values, and needs in breast cancer screening, a brief mixed-methods scientometrics analysis was conducted. This included the most up-to-date global health metrics from open-access databases, specifically from the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) and the WHO Global Health Observatory, focusing on breast cancer. A semi-structured search on PubMed yielded 82 results, from which, after manual review, only 15 original studies were identified worldwide. Only 11 countries have published at least one original article on this topic, with the United States having the highest volume of publications, though with only four articles (Figure 1). When compared to age-adjusted incidence and mortality rates, a significant disparity was observed between the disease burden posed by breast cancer in countries with evidence on preferences, values, and needs in breast cancer screening, and the volume of publications demonstrating a lack of comprehensive understanding of this psychosocial, cultural, and healthcare process (Figure 1).

According to global health metrics, countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, such as Jamaica (35.21), Nigeria (26.8), Iraq (23.51), the Dominican Republic (23.03), Uruguay (21.57) and Colombia (13.29), which have some of the highest breast cancer mortality rates per 100,000 worldwide, lack even a single publication on this topic. These results reflect notable knowledge and population gaps in exploring AI-based health technologies in breast care, which must consider cultural, social, and healthcare aspects essential to ensure the success of these programs.

Why is the evidence on this topic so limited? One possible explanation is that global health efforts have historically prioritized the development of diagnostic infrastructure, workforce training, and imaging availability [9]. But these strategies have not adequately addressed the psychosocial and cultural dimensions of screening programs. This gap contributes to the underutilization of services, late-stage diagnoses, and persistent health inequities.

Recent advances in AI-based breast cancer screening have demonstrated non-inferiority—and in some cases superiority—compared to traditional radiologist interpretations. For example, the MASAI trial [6] showed that AI-supported mammography screening is safe and diagnostically accurate, offering a viable alternative in health systems with limited radiology workforce [6]. Additionally, AI-based imaging tools can be trained to detect abnormalities using diverse datasets, making them adaptable to low-resource settings with limited access to mammography or specialized expertise [8]. These systems are capable of automatically detecting and highlighting suspicious regions in breast images (e.g., microcalcifications, masses, or architectural distortions), providing risk stratification scores, and assisting in prioritizing cases based on severity [8]. Some algorithms generate structured reports or suggest likely diagnoses, facilitating clinical decision-making—especially where radiologists are scarce or overburdened. Others can be integrated with portable imaging devices and operate offline, making them viable in rural and underserved areas without robust internet or power infrastructure [10]. These capabilities reduce diagnostic turnaround time, enhance diagnostic concordance, and improve the accessibility of early detection services while minimizing operational costs [11].

However, despite these technical advances, the effectiveness of such innovations is highly dependent on the degree to which they are acceptable and accessible to the target population. Cultural stigma, fear, mistrust of medical systems, and lack of culturally appropriate health communication have been recognized as key barriers to early breast cancer screening in vulnerable communities [7]. In these settings, invasive procedures or those requiring physical contact may further exacerbate mistrust or fear. In contrast, noninvasive, AI-supported modalities—such as image-based analysis with minimal human interaction—can mitigate these barriers, making women more willing to participate in routine screening [10, 11].

This brief scientometrics analysis reveals a notable gap in the volume and geographic distribution of primary studies exploring women's preferences, values, and needs in breast cancer screening. Countries with the highest age-adjusted mortality rates from breast cancer often have no original research addressing this topic. This finding is consistent with previous literature that highlights a mismatch between the disease burden and the production of locally relevant research [3, 12]. The implications are concerning: in the absence of contextualized evidence, screening programs may fail to reach those at highest risk or may be rejected due to misalignment with community expectations and beliefs [3].

Moreover, emerging research underscores the importance of aligning public health technologies with women's perspectives. Carter et al. [13] found that women are more likely to accept AI-assisted screening when they are informed of the benefits, risks, and implications in a culturally sensitive manner. This reinforces the need to integrate community engagement and health literacy strategies with technological implementation to optimize outcomes [12].

From a health systems perspective, the adoption of noninvasive, AI-supported strategies aligns with global goals such as the WHO Global Breast Cancer Initiative [9], which advocates for scalable, cost-effective interventions tailored to the realities of low- and middle-income countries [9]. These technologies not only reduce diagnostic delays and human resource bottlenecks but also present an opportunity to design more inclusive, responsive, and sustainable screening models. By centering women's preferences and trust in these systems, we can enhance program acceptability and impact, particularly in regions historically marginalized in health innovation efforts [14, 15].

Global health indicators project that, with proper implementation, these technologies could significantly close the gap in access to early breast cancer diagnosis, allowing for more inclusive and equitable care. However, empowerment and a robust approach are required to highlight these opportunities against knowledge gaps, which have been described as risk factors for the failure of screening strategies in low-resource areas with women at high risk of delayed detection of potentially preventable breast cancer.

Author Contributions

Wolmark Xiques-Molina: conceptualization (equal); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Ivan David Lozada-Martinez: conceptualization (equal); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Ornella Fiorillo-Moreno: conceptualization (equal); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Alexis Narvaez-Rojas: conceptualization (equal); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data will be provided upon justified request to the corresponding author.