Elwyn Simons: Opening windows into Madagascar's past

1 INTRODUCTION

Madagascar is a hauntingly beautiful and bizarre land. It is a place of disappearing habitat, challenging landscapes, underdeveloped infrastructure, political turmoil, and complex bureaucracy. Those who come to study its unique fauna, including more than 100 species of extant lemur, tend, themselves, to be remarkable. Thus it should be no surprise to those reading this issue that in 1977, when Elwyn L. Simons was appointed Director of the Duke University Primate Center (now Duke University Lemur Center), a facility where living lemurs are housed, bred, and studied (Wright, 2017), he endeavored to include the extinct “subfossil” (or recently extinct) lemurs of Madagascar under its purview. It was during his years as Director of the DPC that Simons’ legacy as the father of the field of primate paleontology was cemented, partly through his contributions to the recovery and descriptions of these unique animals.

Despite more than a century of strong paleontological interest in the extinct lemurs of Madagascar, many gaps remained in our knowledge of these remarkable creatures until the early 1980s. Very little paleontological field work had been undertaken in Madagascar in the decades following Charles Lamberton's expeditions, which were mainly in the 1930s (Lamberton, 1934; 1938; 1939). After long and difficult negotiations, Simons succeeded, on August 1, 1983, in creating a collaborative accord between colleagues at the Université d'Antananarivo in Madagascar and the Duke University Primate Center whereby field exploration of paleontological sites reopened in Madagascar (MacPhee & Simons, 1983; Simons, Wells, MacPhee, Burney, Chatrath, & Gagnon, 1985).

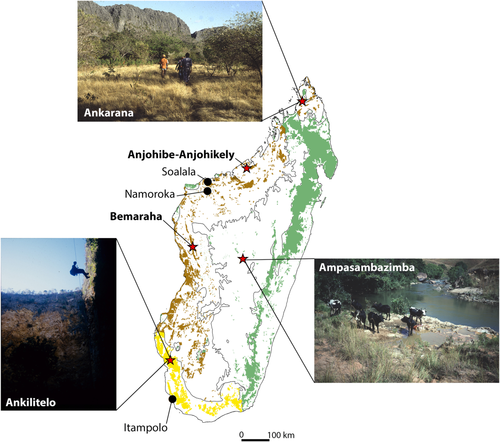

Elwyn Simons was never put off by the difficulty of a mission. Under his guidance, many Malagasy and American students and faculty received training in methods of collection, conservation, and the study of Malagasy subfossils in what are quite possibly the most bizarre places in Madagascar: caves, marshes, and deep pits. Simons explored subfossil sites in almost every corner of Madagascar (Fig. 1). He explored the longest cave systems in Madagascar (Ankarana in the extreme north) and the deepest (Ankilitelo in the southwest). These formidable fossil sites had never before been studied by paleontologists. His expeditions also took him to the Anjohibe-Anjohikely cave system in the northwest, Ampasambazimba on the central highlands, tsingy massifs (in addition to Ankarana) such as Namoroka in the northwest, and Bemaraha in the west, as well as other caves and sinkholes in the southwest.

Map of Madagascar indicating the locations of subfossil localities explored by paleontological teams lead by Elwyn Simons. Red stars indicate localities that yielded significant subfossil collections; black circles indicate less productive or unproductive localities. Photographs highlight the diversity of sites explored: caves such as Ankarana), marsh or riverine localities such as Ampasambazimba, and pits such as Ankilitelo). Lines indicate the major ecological regions of Madagascar; shaded overlay indicates remaining primary forest [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Elwyn and his teams worked at lake and marsh sites such as Ampasambazimba and at caves such as Anjohibe, Ankarana, Ankilitelo. Each was unique and offered particular advantages. At lake, marsh, and swamp subfossil localities, bones are found in anoxic, buffered neutral sediments below the water table in a peat-like matrix containing carbonate sand or some source of moderate alkalinity (Burney, 1999). Without this pH buffering, the buildup of organic acids would have dissolved calcareous bones and shells. Constant flooding by groundwater prevents oxygen from penetrating the sediments and destroying pollen grains and other delicate organic remains. Ancient DNA preservation is sometimes very good in sites of this type (Yoder, Rakotosamimanana, & Parsons, 1999). Sediment cores taken at lake sites can also yield palynological documentation of temporal changes in plant communities and charcoal microparticle documentation of changes in the intensity or frequency of fires (Burney, 1987a, 1987b, 1988; Burney, Burney, Godfrey, Jungers, Goodman, Wright, & Jull, 2004).

However, lake, marsh, and swamp sites tend to yield relatively few primates; instead, bones of crocodiles, hippopotamuses, and tortoises abound. Furthermore, only in exceptional cases are skeletons found intact at such localities. At most lake and marsh sites, fossils found in apparent association show no anatomical relationship to each other and often belong to different taxa. In contrast, caves and rock shelters sometimes preserve entire skeletons in situ. Moreover, primates can comprise up to ∼90% of fossils. Unsurprisingly, then, it was caves that commanded Elwyn's greatest attention through his decades of paleontological work in Madagascar. It was in caves that Elwyn Simons and his collaborators made some of their most spectacular subfossil lemur discoveries.

THE RESEARCH

Elwyn began his paleontological work in Madagascar working with AMNH paleontologist Ross MacPhee, geologist Neil Wells, archeologist Robert Dewar, paleoecologist David Burney, long-time research associate Prithijit Chatrath, and paleontologist Martine Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, then faculty at the University of Madagascar in Antananarivo. In 1983, members of the team visited Anjohibe, a cave near Mahajanga in northwest Madagascar. Within a day of the team's arrival, MacPhee spotted fossils in a horizontal cleft within the cave's main passageway (MacPhee & Simons, 1983). He and Elwyn spent the next two days “spread-eagled with our noses in the mud” (MacPhee & Simons, 1983:19), unearthing these fossils one at a time, gradually assembling what turned out to be the most complete skeleton of a giant lemur, Palaeopropithecus, ever found. This was also the first “new” extinct lemur species recovered by Simons’ expeditions. A few bones belonging to this species had previously been recovered by Joel Mahé (1965) at a nearby marsh site, Amparihingidro; they were already in the collection in Antananarivo. However, it was Elwyn's team members who recognized the novel species status of this animal, referring to these specimens from Anjohibe as “Palaeopropithecus sp. nov.” (Godfrey & Jungers, 2002). The species was given a formal name, P. kelyus, meaning small Palaeopropithecus, after even more specimens were found by a French and Malagasy team at other caves (Belobaka and Ambongonambakoa) located between Amparihingidro and Anjohibe (Gommery, Ramanivosoa, Tombomiadana-Raveloson, Randrianantenaina, & Kerloc'h, 2009).

Perhaps most important was the multidisciplinary nature of research conducted by Elwyn and his collaborators. In 1984, at the start of their work in Madagascar, Simons’ team launched a program, led by paleoecologist David Burney, to reconstruct precontact environments of Madagascar. Working at the marsh site Ampasambazimba in the central highlands, Burney collected samples for dating and pollen analysis from a pit dug by Elwyn and Ross MacPhee (MacPhee, Burney, & Wells, 1985). Burney and Chatrath then took a sediment core for detailed chronological work at a nearby lake, Kavitaha (Burney, 1987b). Burney, MacPhee, and Wells provided the chronological, geological and paleoecological contexts for the important new fossils that the group had unearthed (see Burney, 1999; MacPhee et al., 1985).

In 1985, the team traveled to the arid southwest to look for some classic caves, particularly Itampolo, south of Toliara. That year there was a severe drought in Madagascar; gas supplies were limited and water even more so. Elwyn's team had to “create” its own fresh water by going to the sandy seashore, waiting for low tide, and digging a pit in the intertidal zone. Over time, the pit would fill with brackish water, after which the team would wait for the heavier salt water to settle to the bottom, leaving the lighter, less salty, and marginally drinkable water on top.

During subsequent years, Elwyn initiated new collaborations with students (including Roshna Wunderlich and Charlie Lockwood, to name just a couple) and with faculty who had previously studied subfossil lemurs (Laurie Godfrey and William Jungers). Students and new faculty from the University of Antananarivo (e.g., Jeannette Ravaoarisoa and Gisèle Ravololonarivo Randria) also joined forces. In 1986 and 1987, Elwyn's group returned to Anjohibe and Ampasambazimba, the two sites that had brought him excellent results early on. Now it was possible to generate and compare a full list of primates, extant as well as extinct, that lived or had lived in these parts of Madagascar. Bones of the greater bamboo lemur (now called Prolemur simus) were found to be surprisingly common at Anjohibe. Archaeolemur was the most common extinct lemur. It was now also possible to characterize the Archaeolemur specimens from the northwest as having been quite similar to those from central Madagascar, A. edwardsi. Comparing fossils from different regions of Madagascar, Elwyn's team's research had assumed a biogeographic focus that still frames subfossil lemur studies today.

From 1988 to 1993, Elwyn turned his attention to the expansive cave systems of the Ankarana Massif while also mounting reconnaissance missions to other sites, including the Namoroka and the Soalala region. Ankarana is a 30-km-long tsingy formation with a cliff 200 m high in places in the extreme north of Madagascar, near Ambilobe. There is an underground river more than 10 m wide and very deep in an 18-km-long cave called Ambatoharanana. Crocodiles find refuge there, giving Ankarana its popular name – the crocodile caves. Hitherto, the caves were virtually unknown to paleontology, but Elwyn sensed that the caves held promise. He knew that some excellent maps drawn by French mathematician and spelunker Jean Radofilao (formerly Jean Duflos, and pronounced Ra-Duflos) could help naïve explorers find their way through this massive system of corridors and chambers. Between 1964 and 1975, Radofilao and fellow spelunkers had mapped and explored over 100 km of underground passages: the southern Andrafiabe system (Andrafiabe, Gallery of the Gours Secs, and the Lone Barefoot Stranger Cave); the central Matsaborimanga Caves; and Antsiroandoha toward the northern part of the massif (Duflos, 1966, 1968; Radofilao, 1977). Teams of French, Anglo, and Malagasy ecologists and speleologists had continued the effort (Peyre, Arthaud, Bessaguet, Fulcrand, Martin, Radofilao, Flandin, & Tessier, 1982; Wilson, 1987). In 1981, a Southampton University expedition recovered cranial and postcranial bones of the greater bamboo lemur, Prolemur simus, in one of the caves and exported them to the British Museum (Natural History). Five years later, Vuillaume-Randriamanantena and Ralaiarison-Raharizelina joined another British reconnaissance mission and found many more fossil Prolemur, as well as bones of other lemurs (Vuillaume-Randriamanantena & Ralaiarison-Raharizelina, 1987), thus encouraging Elwyn's involvement. Ankarana became the major focus of Elwyn's work during the late 1980s and early 1990s (Gagnon, Simons, Godfrey, & Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, 1988; Simons, 1993; Simons, Godfrey, Jungers, Chatrath, & Ravaoarisoa, 1995a).

Elwyn's expeditions to Ankarana revealed a subfossil primate fauna very like that of Anjohibe, but richer (Fig. 2). As at Anjohibe, the most common lemurs were Prolemur simus and Archaeolemur sp. cf. edwardsi. The site is also renowned for the discovery of two new species of fossil lemur, Babakotia radofilai (the first new genus of extinct lemur to be found since 1909) and Mesopropithecus dolichobrachion.

Elwyn Simons finding fossils at Antsiroandoha Cave (Ankarana Massif) in 1988 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Elwyn's team first found Babakotia at Antsiroandoha cave in June 1988. Godfrey, Simons, Chatrath, & Rakotosamimanana (1990) named and described the species on the basis of two maxillary fragments and the midshafts of two long bones. They named it “Babakotia” to underscore its close relationship to the living indri, which members of the Betsimisaraka tribe call the “babakoto,” and “radofilai” to honor spelunker Jean Radofilao. Elwyn's expeditions in 1989 and 1990 produced more Babakotia, including some associated bones of a juvenile (Jungers, Godfrey, Simons, Chatrath, & Rakotosamimanana, 1991).

Noone, however, could have anticipated what happened on July 13, 1991, when Ted Roese, an undergraduate student whom Elwyn had brought to Madagascar, explored the cave called Fitsangantsanganan'ilay olona tokana, literally the “place of the walk of the lone person,” so named because of human footprints entering the cave, and none coming out. We called this the Cave of the Lone Barefoot Stranger. The cave's main entrance opened into a seasonally dry but always muddy riverbed. The route was very slippery in places, making walking precarious, and the mud was sufficiently soft to swallow boots. One of the expedition's Malagasy guides had found pieces of a skull and some long bones of a Babakotia on a ledge in the cave. Elwyn Simons and Laurie Godfrey settled at the guide's site to collect all remaining bits, fastidiously wrapping each one first in toilet paper and then bubble wrap. When they finished wrapping all the fragments, they called to Ted, who had been wandering elsewhere in the cave, to help them carry their load. “Ted, can you come here?” They heard a faint response, “I think you'd better come over here!” Muttering and swearing, Simons and Godfrey filled their backpacks with their haul and headed down a slippery slope toward the sound of Ted's voice. They found him, grinning and holding out a perfect skull of a Babakotia.

Ted had seen the proximal end of what he thought was a stick in the middle of some standing water. When he removed the stick, he saw it was a radius. Then, groping under water, he felt what at first seemed to be a rock, but proved to be a skull. Godfrey and Simons sensed that this might be a spectacular find. The next day, several members of the expedition joined Ted at his site, buckets in hand, to remove the standing water and exhume what did indeed turn out to be a remarkable skeleton of Babakotia, complete with rarely found elements such as a baculum (penis bone) and the distal phalanx of the second pedal toe that supports the grooming claw.

In 1994, Elwyn turned his attention to southwestern Madagascar. Along the western margin of the Mahafaly Plateau in southwestern Madagascar, there are numerous shafts that contain subfossil bone, although at that time no true horizontal cave passage development had been found (Middleton & Middleton, 2003). Many of the caves are collapse dolines of depths up to 18 m (Bonnardin, 1988). Consequently, this region has been dubbed the zone des avens (“zone of sinkholes”) (MacPhee, 1986). Often these caves yielded both megafaunal and microfaunal remains. Because small animals from the region surrounding a cave are usually brought in as prey by avian or mammalian carnivores, cave sites can act as complex natural sampling devices for microfauna (Andrews, 1990; Wang & Martin, 1993; Wolverton, 2001, 2006). In contrast, at open-air sites, microfauna usually are not recovered unless special provision is made to screen for small material.

In particular, the area located between the Manombo River to the north and the Fiherenana River to the south has a depth potential of 400 m (Bonnardin, 1988). In fact, very deep vertical shaft caves are common in this area (Du Puy & Moat, 2003; Middleton & Middleton, 2002). These localities are referred to as gouffre caves, meaning “abyss” or “bottomless pit” in French (Simons, Simons, Chatrath, Muldoon, Oliphant, Pistole, & Savvas, 2004). Caves of up to 200 m in depth had been explored, mainly by French cavers (Middleton & Middleton, 2003). Although Elwyn recognized that the potential for cave discovery was considerable, the plateau environment is significantly hostile to exploration. It is hot, arid, difficult to access, and awkward to traverse across its rough solutional channels, dry valleys, and many sinkholes (Middleton & Middleton, 2002; Simons et al., 2004). Given the harsh working conditions and the inaccessibility of most of the region, these caves had been largely ignored by paleontologists. It is necessary to maneuver over and around giant boulders and occasional felled trees, while deep ruts in the road must be straddled. It might take 20 hours of driving to progress a little more than 30 km. Crew members had to run ahead clearing rocks and creating negotiable paths. Driving into the region therefore took the better part of a day or longer, and since the unpaved part of the trail measured only 40 km in length, most people could easily walk this distance faster than it could be covered by car.

Safety was always Elwyn's primary concern, but he was very good at assembling excellent teams of cavers and scholars and getting results. One cave in particular, Aven des Perroquets, or Kintsia'ny Sihothy in Malagasy (meaning “Cave of the Parrots”), a tribute to a pair of large black vasa parrots that nest in its walls (Decary & Keiner, 1971; Peyre, 1986), seemed to Elwyn to be a natural trap. Like the Natural Trap Cave in the Pryor Mountains of Wyoming (Martin & Gilbert, 1978; Wang & Martin, 1993, it could have functioned as a collector of animal life. The villagers of Manamby informed Simons that the local name for the Aven des Perroquets is Ankilitelo, which means the cave “at the three kily (tamarind) trees” (Hildreth, 1998). Unlike typical cave systems in Madagascar, Ankilitelo consists of a narrow vertical shaft of 145 m (nearly 500 ft) in depth and is accessible only by a single entrance (Simons et al., 2004; Muldoon, DeBlieux, Simons, & Chatrath, 2009; Muldoon, 2010). Positioned directly under the shaft on the floor of the cavern is a massive, cone-shaped pile of mud and debris with a very high concentration of bone.

Gouffre caves such as Ankilitelo pose unique problems for subfossil collection because of the great technical difficulty and physical rigor of access, which can be achieved only by professional cavers and paleontologists trained in climbing techniques. Few researchers have descended into Ankilitelo, the deepest cave known in Madagascar. Those who did had to practice their techniques on baobabs and shorter caves before receiving Elwyn's consent to begin.

Ankilitelo is more than 230 m deep at the lowest level. The crew included professional cavers Mark Minton, Matthew Oliphant, and Nancy Pistole, and two paleontologists, Don DeBlieux (Utah Geological Survey) and Tab Rasmussen (deceased, of Washington University), who repeatedly made the perilous descent. Entering the cave requires an initial controlled rope descent of more than 145 m, straight down a narrow shaft 5-8 m in diameter. That means descending a rope like a spider every morning and climbing back out toward the end of the day with the fossil bounty (Simons et al., 2004). The team's first descent was unsuccessful because Matt Oliphant ran out of rope 30 feet above the cave floor. He would have had enough rope, but Don DeBlieux had taken one of the three available ropes to explore another cave. As soon as all three ropes were assembled at Ankilitelo, the team witnessed the extraordinary fossil wealth of the cave. Ankilitelo became the focus of Elwyn's research in the southwest. He would have loved to descend into the cave himself, but it was too dangerous, and there was no way for the team to lower him into it or help him ascend. His disappointment was short-lived, however, as the team brought Elwyn many fossils to examine at the camp (Fig. 3). In future years, Elwyn made sure to bring lots more rope and more equipment for the road trip itself – more tow straps, winches, and saws.

Elwyn Simons in 1997 at the camp at Ankilitelo, examining the bounty of fossils that had emerged from the pit [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Since 1994, paleontological work at Ankilitelo Cave has unearthed, in addition to new specimens of giant lemurs, an abundance of bones of still-extant small mammal species. These, along with small vertebrate specimens from other subfossil sites in Madagascar, have the potential to uncover prehistoric changes in the geographic distributions of living species (Muldoon et al., 2009). They also provide a framework within which changes in community composition and structure can be evaluated (Muldoon, 2010).

2 THE PUBLICATIONS

The ∼40 publications on subfossil lemurs penned by Elwyn Simons and collaborators feature diverse topics. These include lemur systematics and phylogeny (Godfrey et al., 1990; Jungers et al., 1991; Simons, Godfrey, Jungers, Chatrath, & Rakotosamimanana, 1992; Tattersall, Simons, & Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, 1992; Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, Godfrey, Jungers, & Simons, 1992; Simons et al., 1995a), past versus present biogeography, temporal ranges of subfossil lemurs, community characteristics, and the chronology of extinction of large lemurs and associated fauna (Jungers, Godfrey, Simons, & Chatrath, 1995; Simons, Burney, Chatrath, Godfrey, Jungers, & Rakotosamimanana, 1995b; Godfrey, Jungers, Reed, Simons, & Chatrath, 1997; Simons, 1997; Godfrey, Jungers, Simons, Chatrath, & Rakotosamimana, 1999; Godfrey, Simons, Jungers, DeBlieux, & Chatrath, 2004a; Muldoon & Simons, 2007; Muldoon et al., 2009; Muldoon, Crowley, Godfrey, Rasoamiaramanana, Aronson, Jernvall, Wright, & Simons, 2012; Muldoon, Crowley, Godfrey, & Simons, 2017). Other topics are reconstructing the behavior of extinct animals (Jungers, Godfrey, Simons, Wunderlich, Richmond, Chatrath, & Rakotosamimanana, 2002), subfossil lemur ontogeny, dental microstructure and life history (Ravosa & Simons, 1994; King, Godfrey, & Simons, 2001; Schwartz, Samonds, Godfrey, Jungers, & Simons, 2002; Ravosa, Stock, Simons, & Kunwar, 2007), dental microwear and occlusal texture analysis (Godfrey, Semprebon, Jungers, Sutherland, Simons, & Solounias, 2004b; Scott, Godfrey, Jungers, Scott, Simons, Teaford, Ungar, & Walker, 2009), semicircular canal systems (Walker, Ryan, Silcox, Simons, & Spoor, 2008), hand and foot anatomy (Wunderlich, Simons, & Jungers, 1996; Jungers, Godfrey, Simons, & Chatrath, 1997; Hamrick, Simons, & Jungers, 2000; Jungers, Lemelin, Godfrey, Wunderlich, Burney, Simons, Chatrath, James, & Randria, 2005), vertebral anatomy (Shapiro, Seiffert, Godfrey, Jungers, Simons, & Randria, 2005), and field work adventures in Madagascar (Simons, Godfrey, Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, Chatrath, & Gagnon, 1990; Simons, 1993; Simons et al., 2004). Elwyn's expeditions were responsible for the description and discovery of new species of extinct lemur (Godfrey et al., 1990; Simons et al., 1995a) and led to the recognition of numerous new skeletal elements of previously known extinct lemurs (Hamrick et al., 2000), as well as the unearthing of some of the most complete extinct-lemur skeletons ever found (MacPhee & Simons, 1983). Elwyn's group not only introduced the term “sloth lemur” to the literature, but did more to expand our knowledge of this group than anybody had done in the past (MacPhee & Simons, 1983; Godfrey et al., 1990; Simons et al., 1992; Simons et al., 1995a; Godfrey & Jungers, 2003). In addition, since Elwyn himself had always harbored a fascination with living aye-ayes, it is no surprise that one of his articles focuses on its extinct relative, the giant aye-aye, Daubentonia robusta (Simons, 1994). Moreover, fossils collected by Elwyn's teams have contributed to our radiocarbon and stable isotope databases on subfossil lemurs (Simons, 1994, 1997; Simons et al., 1995b; Burney et al., 2004); preservation of organic material has proven to be particularly good at Ampasambazimba and Anjohibe. It is not hyperbole to state that over the past 50 years the work of Elwyn Simons influenced more people in paleoanthropology than did that of any other person. He created a space within the field to study the evolutionary lineage of primates, not just humans, and placed importance on the relationships between extinct and extant lemurs.

3 THE COLLEAGUE

Elwyn Simons was also personally enchanting and his story-telling abilities were legendary. There were many days when, after the hard work was finished, there was laughter and merriment at the field camp. Not uncommonly, Elwyn would take center stage; he was as comfortable reciting Geoffrey Chaucer's poetry, which he had memorized, as he was reciting bawdy limericks. When asked for information that he preferred not to divulge, he might say “You're too young to know.” If anyone emerged from a day's work without fossils or claimed anything he deemed silly or irrelevant, he might teasingly admonish that person by announcing, “You're fired!” He loved astronomy, and field sites in Madagascar became wonderful laboratories for Southern Hemisphere star gazing after the generator was shut off at night. Elwyn also captivated his audiences by telling stories of his expeditions on other continents or about his formative years. He was fond of ending all stories with the phrase, “and then they all died.” He delighted in word play and creating new words, like “Arch-ee-old-lemur” for Archaeolemur, “Ape-idiom” for Apidium, “die of rear” for Montezuma's revenge, “prime rots” for primates, “feel awful” for falafel, and so on. Once he recounted the story of how he became a paleontologist. He was about three years old at the time and his dad had taken him for a visit to the Chicago World's Fair. He rode piggy-back on his father's shoulders so he could get a better view of the displays. But upon seeing the formidable animated skeletal models of Triceratops and especially “Brontosaurus” with its swinging neck and groans, little Elwyn began to wail, “Take me away!” His dad carried Elwyn away as fast as he could, but as soon as the models were out of sight little Elwyn was still wailing. This time the cry was, “Take me back!!!” From that moment on, Elwyn Simons was a paleontologist! He was sometimes controversial, never boring, driven by a thirst for knowledge and possessing an uncanny gift of being able to find the right fossil in the right place at the right time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Friderun Ankel-Simons, Don DeBlieux, David A. Burney, Bill Jungers, Cornelia Seiffert, and Erik Seiffert who provided information, as well as some of the photos presented here. We thank Brent Adrian for his help with the map in Figure 1. We gratefully acknowledge the support of our colleagues at the Université d'Antananarivo, who were essential research partners and who provided logistical support for all expeditions.