Survey of an online system for information to women with epilepsy of childbearing age and management during pregnancy: A 3-year evaluation

Abstract

Objective

We developed an online tool for women with epilepsy consisting of two modules: one with information on pregnancy-related issues (information module) and one for reminders about blood test and communication about dose changes (pregnancy module). Our aim was to assess perceived value, user-friendliness and improvement of patient knowledge in users.

Methods

The system was launched in 2019 and patients invited by epilepsy nurses were asked to participate in a survey 1 month after the invitation for the information module, and 1 month postnatally for the pregnancy module.

Results

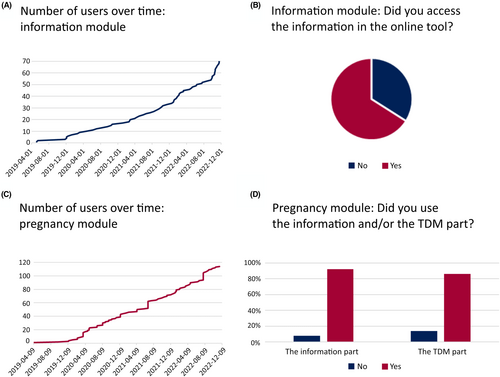

By November 2022, the system had been used by 96 individuals out of 100 invited in the pregnancy module, in a total of 114 pregnancies. One hundred and eleven women had been invited to the information module, and 70 of these accessed it. The survey received 96 answers (44 information, 52 pregnancy). User-friendliness was rated as good or very good by a little over half of the users; 55% in the information module and 52% in the pregnancy module. Among pregnant women, 83% found the TDM part useful and most would prefer a similar system in future pregnancies. Sixty-four percent of users of the information module and 48% of the pregnancy module found that the system had increased their knowledge. Two knowledge questions were answered correctly by a significantly higher proportion of those that had accessed the online information.

Significance

There was great demand for online communication during pregnancy and our experiences of implementation can hopefully assist digitalization of epilepsy care elsewhere. Online information also seems to increase knowledge about pregnancy-related issues, but our invitation-only method of inclusion was not effective for widespread dissemination. Patient-initiated access with optional epilepsy-team contact if questions arise could be an alternative.

Plain Language Summary

We have performed a survey of users of a new Internet-based tool for information to women of childbearing age and communication about dose changes during pregnancy. Users were overall satisfied with the tool and answered some knowledge questions more accurately after accessing the information.

Key points

- We developed two online modules for women with epilepsy; one with information and one for management during pregnancy.

- Access was by epilepsy nurse invitation, 96 women responded to a survey one month after invitation (information) or delivery (pregnancy).

- Patient satisfaction was high. Online information increased patient knowledge subjectively and according to knowledge questions.

- Although most patients would prefer online managment in their next pregnancy, some wished to use telephone (only or as a supplement).

- Demand for the information module before pregnancy was less then expected; patient-initiated access could be a better option.

1 INTRODUCTION

Management of epilepsy in women of childbearing age is an important part of epilepsy care. Preconceptual guidance should cover contraception, fetal risks regarding teratogenicity and maternal risks related to antiseizure medication (ASM) pharmacokinetics.1 Advice on contraception is important to allow patients to make well-informed decisions about pregnancy and time to optimize ASM therapy. During pregnancy, dosage of several ASMs needs to be adjusted based on therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). Persons with epilepsy desire advice on reproductive issues from their epilepsy care providers,2, 3 but many do not receive adequate counseling.4, 5 Rates of information on pregnancy-related issues vary greatly with study methodology and setting; only 7% of women had documented advice in a cross-sectional single center US study, whereas about 45%–60% of women taking self-selected internet surveys remember being given information.4, 6, 7 Disparity can also be an important factor; lower rates of good care have been reported in socioeconomic weaker groups.8 In summary, there is a need for structured and scalable methods of providing pregnancy-related information and rapid communication with epilepsy care providers in an efficient and timely manner prior to and during pregnancy.

The digitalization of epilepsy care and telemedicine was greatly accelerated by the pandemic,9-11 but digital patient education tools, remote delivery of epilepsy care, and smartphone apps to study ASM compliance during pregnancy existed before.12-14 In 2019, we developed an online tool for information on pregnancy-related issues for women with epilepsy and for communication regarding therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and dose adjustments during pregnancy.15 The tool was primarily designed to facilitate communication and reduce the need for telephone contacts between epilepsy nurses and patients. Since the launch, patients have been invited to a survey on user-friendliness of the system and a test of knowledge on pregnancy-related issues. Patient satisfaction was high in an early interim analysis.15

We now report the final analysis of the quality assurance project run in parallel with the launch of the system. After 3 years, the system has become integrated into clinical practice and the dominating mode of communication with women with epilepsy during pregnancy. The primary aim of our quality assurance project was to assess whether the online system was used, patient-perceived value and user-friendliness, and effect on QoL and anxiety/depression scores between users and non-users. The secondary aim was to assess if the information provided online improved patient knowledge of pregnancy-related issues.

2 METHODS

2.1 Setting

The project was conducted at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, the only tertiary epilepsy center in western Sweden, with a local catchment area of approximately 0.9 million covering mainly the city of Gothenburg. The study was a cross-sectional survey.

2.2 Online tool

The online system has been described previously.15 Briefly, it is based on the Swedish national online Patient Portal (www.1177.se),16 and consists of two modules: one containing information for all women with ASM-treated epilepsy of childbearing age and the other offering communication during pregnancy. The information module contains information on ASM interactions with contraceptive pills, malformation risks, advice on folic acid supplementation, delivery, safety issues, and breastfeeding. Ideally, patients are given access to the information module well in advance of pregnancy as part of routine care, and then invited to the pregnancy module in early pregnancy. The pregnancy module contains some knowledge content related to pregnancy (the importance of TDM and contacts with the epilepsy nurse) and the postnatal period (safety, breastfeeding), but mainly an interactive part in which the epilepsy nurse sets a schedule for TDM, and messages are sent to the patient at set intervals as a reminder for blood tests. The pregnancy module is a custom-designed interactive form that is sent to the patients at each TDM time point with questions on pregnancy week, current ASMs and doses, seizure status, and a confirmation that the patient has taken a blood test. A smartphone app connected to 1177.se can be used for the communication in the module. The system allows the nurse to monitor forms that are sent to patients, and flags those that are unanswered, to allow traditional telephone contact. Upon receiving a TDM laboratory result, the nurse writes to the patient about the new dose, which the patient acknowledges.

We use standardized TDM intervals (monthly for lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine, every 3 months for carbamazepine and topiramate), but these can be modified by the nurse or treating physician. The module also allows scheduling of extra blood tests if needed.

2.3 Study population

Women of childbearing age (not defined, but generally women <50 years) with epilepsy seen by epilepsy nurses from October 2019 until November 2022 were offered to get access to the online tool, as a supplement to standard care, and simultaneously offered to participate in a research project evaluating the tool. Inclusion criteria were patients invited by the epilepsy nurse to use the tool that were also able and willing to consent to a follow-up survey. Epilepsy nurses could invite users of the information module at their discretion. Clinical work-load may have affected invitations to that module, since instruction and starting new users took some time for the nurses. The pregnancy module quickly became standard-of care and all women that were interested in using an online system were offered to use it. All users were invited to answer the surveys. The pregnant women were invited to participate in the study as soon as they had reported their pregnancy to our nurses or physicians. The majority of the pregnant women were in their first trimester when they were included, but the exact time of inclusion was at the discretion of the nurses.

Recruitment was not consecutive, but opportunistic. The prespecified protocol stated that two analyzes should be performed; one early on feasibility, safety, and patient satisfaction15 and the present one. The online tool was launched in June 2019 and the initial analysis was performed in October 2020. We had initially planned to include 100 participants in each survey until the end of 2022, but because of slow recruitment, in part but not solely related to resource reallocation during the pandemic, we did not reach the target. Recruitment was stopped according to the initial time plan but short of the recruitment target in October 2022.

2.4 Questionnaire and response rate

A survey assessing patient experience of the Internet-based tool, hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS),17-19 RAND-36,20 and knowledge questions on pregnancy-related issues in epilepsy (adapted from Knowledge on women's issues and epilepsy, KOWIE-I)5 was distributed by mail 1 month after the invitation to the information module and 1 month after delivery for the pregnancy module. The survey (Appendix S2) contained questions about the user-friendliness and perceived value of the online tool. The RAND-36 questionnaire is a general health-related quality of life score, validated in Swedish.20 It is a self-assessment questionnaire that consists of 36 questions grouped into eight scales: physical functioning, role-functioning/physical, pain, general health, energy/fatigue, social functioning, role-functioning/emotional, and emotional well-being. An additional item asks about health change in the past year. Scale scores are summed and transformed into scales ranging from 0 (worst possible health state) to 100 (best possible state). The knowledge questions were translated from a previous report of KOWEI-I5; we limited the knowledge part to five questions that covered the information provided in the online modules (Appendix S1). The survey took 10–15 min to answer. There was no pretesting of the survey (Swedish ethical rules do not allow pilot-studies without ethical approval).

Patients with miscarriage were excluded. Response rate was calculated as proportion of responses out of the number of individuals invited to the online system.

The survey was not anonymous. Because of the relatively low number of women with new-onset epilepsy or pregnant women seen at each given point in time in our epilepsy service, and the occurrence of indirect identifiers like time since pregnancy—anonymity was not practically possible. The survey was conducted as a health-care quality assurance project and patient data protected by patient confidentiality laws, and all research analyzes were done on pseudonymized data. Electronically stored data were protected by Swedish privacy laws and all data were handled in accordance with the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation).

2.5 Statistical analysis

SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for all analyzes. Categorical variables including survey answers are presented as proportions of responses to that particular question, with 95% confidence intervals. Fisher's exact test was used for comparison of proportions. Mann–Whitney was used for comparison of continuous variables. The threshold for statistical significance was p < 0.05.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Response- and use rate

Since the launch in 2019 until November 2022, 111 women had been invited to the information module, and 70 of these actually accessed it. There had been 100 women invited to the pregnancy module and 96 actual users, with altogether a total of 114 pregnancies (Figure 1). We received 44 (39% of all potential users) and 52 (52% of all potential users) survey answers, respectively. For the information module, 66% (95%CI: 51–79) of responders had accessed the online information. For the pregnancy module, 92% (95%CI 83–97) of responders had accessed the online information, and 86% (95%CI: 74–93) had used the TDM module.

3.2 Responder characteristics

Age and epilepsy characteristics of the responders are presented in Table 1. Most users of the information module had not been pregnant previously but were planning pregnancy in the upcoming 2 years. Users of the pregnancy module were older and a smaller proportion had experienced seizures in the last 12 months compared to users of the information module (p < 0.02). A majority of the users of the pregnancy module had completed university education.

| Information | Pregnancy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | Range | n | Mean | Range | |

| Age | 44 | 28 years | 18–37 | 52 | 33 years | 20–43 |

| Epilepsy duration | 36 | 9.5 years | 45 | 13.5 years | ||

| n | % | 95%CI | n | % | 95%CI | |

| Polypharmacy | 11/41 | 27 | 15–42 | 6 | 12 | 5–22 |

| Seizure in last 12 months | 22 | 50 | 36–64 | 10 | 19 | 10–31 |

| Planning pregnancy | 25/42 | 60 | 45–73 | |||

| Completed education | ||||||

| Secondary | 5 | 11 | 5–23 | 1 | 2 | 0–9 |

| High school | 21 | 48 | 34–62 | 16 | 31 | 20–44 |

| University | 18 | 41 | 27–56 | 35 | 67 | 54–79 |

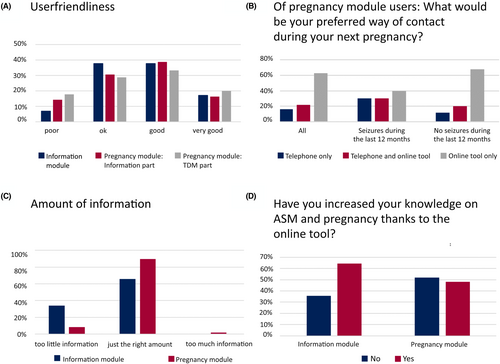

3.3 User-friendliness and amount of information

The user-friendliness of the tool was rated as good or very good by a little over half of users of both modules (Figure 2); 55% (95%CI: 38–72) in the information module and 52% (95%CI: 39–65) in the pregnancy module. Regarding amount of information, 90% (95%CI: 79–96) of users of the pregnancy module found this to be sufficient. A greater proportion of users (35%, 95%CI: 19–53) of the information module would have liked more information, compared to 8% (95%CI: 3–18) of users of the pregnancy module. Sixty-four percent (95%CI: 46–80) of users of the information module and 48% (95%CI: 35–62) of users of the pregnancy module found that the system had increased their knowledge on pregnancy-related issues.

3.4 Experiences during pregnancy

Some questions in the survey were unique to users of the pregnancy module.

Nineteen percent (95%CI: 10–31) had seizures during their last pregnancy and 86% (95%CI: 74–93) had their ASM dose changed. Sixty-four percent (95%CI: 50–76) found reminders to leave blood levels useful and 83% (95%CI: 70–91) found receiving online instructions regarding dose changes useful. Most women would prefer to use a similar system in future pregnancies (Figure 2); 63% (95% CI: 49–75) would prefer the online tool only and 21% (95%CI: 12–34) would like to use the online system with supplemental telephone contacts. Importantly, 37% (95% CI: 25–51) wished to have at least some contact via telephone and 16% (95% CI: 8–27) preferred telephone contact only. Preferring online communication only seemed more common among women without seizures in the last year, but the difference in proportions was not significant (p = 0.156). Preferring telephone contact only was more common among users rating user-friendliness as poor (p < 0.001). The proportion of participants preferring online communication only was greater among participants with university education (p < 0.03).

3.5 QoL and anxiety/depression

Among users of the information module, there were no significant differences in HADS or RAND scores between responders stating that they had or had not taken part of the content online. For the information module, the mean HADS anxiety was 9.8 in users that had accessed the system, versus 10.1 in those that had not (p = 0.91). For HADS depression, the corresponding scores were 4.1 and 5.3 (p = 0.44).

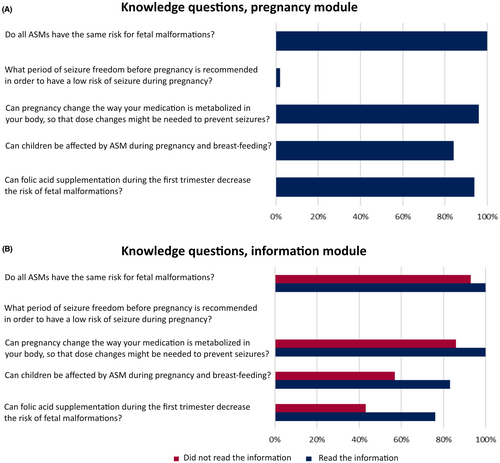

3.6 Knowledge questions

The survey also included questions testing patient knowledge on pregnancy-related issues (Figure 3). For users of the pregnancy module, almost all had accessed the information so comparison between non-users and users was not possible. Responses to the knowledge questions were correct in most cases, except for the question about desirable length of preconceptual seizure freedom. For the information module, we categorized responders by statements on whether they had accessed the online content or not. Broken down by questions, the greatest difference was seen for that about pharmacokinetics and folic acid supplementation; the proportion giving the correct answer to these questions was significantly greater among responders stating that they had accessed the information (p = 0.026 and 0.034, respectively). Just like for pregnant women, the question about the desired minimal length of seizure freedom for low seizure-risk during pregnancy was most difficult also for users of the information module.

3.7 Qualitative information

The surveys offered room for free text. These comments included appreciation of the possibility to communicate remotely with nurses, that user friendliness could be improved regarding notification settings and the need to log in to the national patient portal, and that emotional aspects of reproductive issues were not well covered in the online content.

4 DISCUSSION

Our main finding is that online information about pregnancy-related issues and communication about TDM and dose adjustment is used and appreciated among a majority of patients. Users perceived the information as valuable, particularly before pregnancy, and that the online system had increased their knowledge on pregnancy-related issues. Regarding the secondary questions, women stating that they had accessed the online content responded better to the best of our knowledge test than women that had not accessed the content. Our study also contains important lessons for future development of similar solutions, particularly about the timing of invitation, the amount of information, and the need to maintain traditional telephone-based options.

Regarding use, both modules were easily implemented in standard care and used. The pregnancy module quickly became standard-of-care and was used for most women, with only a handful exceptions (no Swedish language, no access to the general patient portal, etc.). Patients were however given access to the information module at a slower pace than expected. There could be several reasons for the relatively modest interest in the information module, related to both patient and health service factors. Because of the novelty of the system, we decided on an invitation-only approach, requiring patients to be actively invited by nurses. This was to ensure personal communication to handle questions that might arise from the online information. Most women seeing the epilepsy nurse will according to our standard of care receive oral advice on pregnancy-related issues at the same visit. They may therefore feel little need for an online supplement. From the nurse's perspective, there are generally many issues to cover in a short visit, so explanation of and invitation to an online platform may not be a top priority. Our department has about 2500 patients with epilepsy, out of which about a fourth should be women of childbearing age, but estimating the proportion that should have been given access to the tool in an ideal situation is difficult, there are a number of reasons why a woman of childbearing age may not wish access to the online information, including not planning any pregnancy. There may also be a language barrier and some patients may not be deemed suitable by the nurses with regard to cognitive level of function. The situation is slightly different for the pregnancy module, where there is a direct benefit of using the online system. From a system perspective, and as illustrated by the knowledge questions discussed below, more information is needed to more women before pregnancy, so our model with active invitation by the nurse at visits is probably not optimal. Factors influencing the nurse's decision who to invite to the information module is an interesting area for future research. Another interesting area for future studies could be user latency—how long after being granted access and how many times do women with epilepsy access the online information?

The survey response rates were relatively low. This could be due to the fact that many women invited for the information module did not yet consider pregnancy, chose not to access the online tool, and perhaps deemed the survey irrelevant. We also distributed the survey relatively soon (1 month) after the invitation to the information module, which could have led to patients wanting to access the system later not responding to our survey. For the pregnancy module, we believe many of the women were already in close contact by telephone with the nurses and may feel that they had delivered feedback on the tool directly. Due to the high number of participants and data collected during several years with the online tool, we believe that the results could still be valuable for similar development work elsewhere. The response rate can have influenced the findings by responders perhaps being more negative or positive to the tool. In future studies, surveys linked directly to the online systems are probably preferable. The nature of the questions in the survey makes it unlikely that patients will have adapted their answers because of lack of anonymity—participants were not asked to comment on their epilepsy care or epilepsy care providers, but simply on the online system.

Almost half of users of the information module were not seizure-free, which suggests that the current approach catches mainly newly diagnosed or difficult-to-treat epilepsy—those categories most likely to see the nurse. For broader dissemination, automatic or patient-initiated invitations are needed. On the other hand, pregnancy-related information is not trivial and needs to be tailored. Physical meetings with a neurologist have at least in one study been found to be the preferred method of receiving information on pregnancy-related issues in epilepsy,4 so we are reluctant to completely decouple the online module from physical appointments or at least established contact with the epilepsy team.

The clinical value of the online information and communication during pregnancy is difficult to assess. For the information module, those participants who had accessed the information answered more correctly to knowledge questions, but whether this translates to behavior is not known. In Sweden, food products are not fortified with folic acid, making information on adequate use of folate supplement before conception particularly important. That a greater proportion of users of the information module answered the knowledge question on folic acid correctly is encouraging, and future studies should look at translation of this into adequate folate use prior to pregnancy. Among pregnancy module users, almost all responders had used the system, so we could not evaluate whether such use was associated with compliance or break-through seizures. Whether online information and communication have clinical benefits with regard to seizure control is a subject for future and larger studies, for ethical and methodological reasons such studies could perhaps benefit from a cluster design, in which centers adding online care are compared to those using traditional methods only.

Regarding the amount of information, we found that a significant proportion of women using our information module asked for more information than our system provided. This group also wanted more information compared to the users of the pregnancy module. Selection may play a role: Users of the information module have probably self-selected based on a desire to be informed, whereas users of the pregnancy module may have opted to use the system for the convenience of remote communication about TDM and dose adjustment. Another possible contributor to the difference is that a substantial proportion of users of the information module planned pregnancy in 2 years, whereas users of the pregnancy module responded to our survey after completion of a successful pregnancy. Users of the pregnancy module may also have been previous users of the information module. Nonetheless, our results suggest that more information is desired by women with epilepsy at an early stage.

Another lesson is that online communication does not fit all patients. A significant minority still wished to have telephone contacts with nurses, particularly so if they had experienced recent seizures. The education level of responders to our survey were both encouraging and disappointing. Forty percent of users of the information module had a university education, which fits very well with the proportion seen in a recent register-based study of all women with epilepsy without intellectual disability in Sweden.21 However, 67% of users of the pregnancy module had a university education. This could suggest that our system mainly enhances the epilepsy care of patients of a high socioeconomic position. Active counter-measures, such as translation into other languages than Swedish, are needed. Other measures could include simplified invitation to the system with a possibility for patient-initiated access, the system was not perceived as user-friendly by many users. Internet access is almost universal in Sweden, but in other countries, disadvantaged groups may be more reachable by text message-based systems.22

Methodologically, we relied on user-surveys, with associated strengths and weaknesses. The benefits include obtaining information directly from users, which is likely to be more informative than administrative data or secondary sources like medical records. The main drawback is selection bias; responders are probably somewhat more likely to be overly optimistic or critical of the online system. Importantly, our method of offering the online modules as a complement to standard care selects for patients interested in online care delivery, and therefore, it is important not to generalize the findings to broadly. Certain patients are most likely not suited for an online tool and must be provided telephone calls and visits with nurses to be well informed both before and during pregnancy. Further, similar limitations include that we could not recruit all women of childbearing age due to cognitive abilities of the patients, lack of knowledge of the Swedish language, and unwillingness to participate in a few cases. We also did not use validated measurement instruments of user-friendliness, but created our own survey with very intuitive and broad answer categories. If several systems for online care delivery to women with epilepsy are developed in the future, use of more standardized measurements could probably be informative for comparisons.

In summary, we conclude that online communication during pregnancy for dose adjustments has worked very well and largely replaced standard telephone-based communication during pregnancy at our center. Online information about pregnancy-related issues increased patient knowledge about such matters subjectively, and in some aspects objectively. Hopefully, our experiences during implementation can help in similar digitalization efforts in the care of women with epilepsy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

JZ reports speaker honoraria for non-branded educational events organized by UCB and Eisai and as an employee of Sahlgrenska University Hospital (no personal compensation) being investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Bial, GW Pharma, SK life science, and UCB.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Authority (no 2019–02630), the relevant government agency. All patients provided written informed consent. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data of the study are protected by confidentiality laws and cannot be shared by the authors.