“Plok-plok” syndrome: Posttraumatic stress disorder following an SEEG thermocoagulation and direct electrical stimulation procedure

Abstract

The psychological impact of intracerebral electroencephalography (stereoelectroencephalography [SEEG]) including the thermocoagulation procedure has not yet been clearly studied. We present a case of a patient who, following an SEEG procedure for presurgical evaluation of intractable focal epilepsy, developed severe symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Such an occurrence may be under-estimated. Perceived traumatic exposure during SEEG and the development of posttraumatic psychological symptoms should be further studied in order to define risk factors and to improve the monitoring and psychological management of patients during their hospitalization. A careful and systematic procedure of prevention and support before, during, and after SEEG could decrease the risk of development or worsening of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Permets-moi de trouver un endroit où je puisse trembler en paix.

Allow me to find a place where I can tremble in peace.1

1 INTRODUCTION

One third of patients with drug-resistant focal epilepsy may be eligible for surgery. Stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) is required in many cases for localization of the epileptogenic zone (EZ) in order to guide resective surgery.2 During the SEEG procedure, direct electrical stimulation (ES) is often a very useful component in defining the EZ.2-5 In addition, over the last 10 years, SEEG-guided radio frequency thermocoagulation (RF-TC) has been increasingly employed to induce RF-TC lesions prior to SEEG electrode removal, with a goal of reducing seizures and helping with surgical prognostication.6

While SEEG is a widely used procedure for presurgical evaluation, and ES and RF-TC are commonly performed during the SEEG procedure, the psychological consequences of these approaches have not previously been studied.

Moreover, while 310 million major surgeries are performed each year worldwide, very little data exist on the psychological and psychiatric risks.7 However, literature exists on the long-term effects of awake surgery, which may inform us about psychiatric risks associated with neurosurgery and SEEG. Awake craniotomy is associated with a risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).8 A study on the psychological sequelae of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) showed that the reported prevalence of PTSD ranged from 11% to 27%9 and anxiety and pain during intraoperative awareness would increase the risk of developing PTSD.10

There are little data on the psychological effects of SEEG; a single study that focused on long-term effects showed that SEEG and seizure freedom were associated with improved quality of life but not mood. According to the authors, this shows that the assessment and treatment of psychological comorbidities in epilepsy should be addressed independently of the status of seizure control.11 This is especially important given that epilepsy is strongly associated with anxiety and depression12 and PTSD,13 being thus higher than in the general population. Here, we report the case of a patient who developed severe symptoms of PTSD following an RF-TC and ES procedure in the context of SEEG based on a specific interview conducted by a psychologist 4 months after the intervention.

2 CASE STUDY

2.1 Methodology

All of the following descriptions are from the patient's reported experience of the SEEG examination that the patient underwent from February 21, 2021 to March 8, 2021. During a consultation that was conducted in June 2021, she reported to her neurologist that she had been living with severe psychic distress for several months as a result of the SEEG. A clinical semi-directed interview, based on the DSM five criteria,14 was conducted with a psychologist on June 24, 2021 to report her experience in the context of this case report.

2.2 Presentation and medical and psychological history

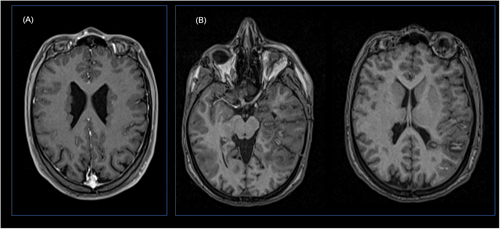

A 27-year-old, right-handed woman presented with epilepsy that appeared at the age of 15 years in a context of bilateral nodular periventricular heterotopia (Figure 1A) related to a mutation of the filamin A gene. Seizure semiology was characterized by language disturbance, notably word-finding difficulties, and various objective signs (loss of awareness, clonic jerks, automatisms). At the time of SEEG, seizures occurred daily and were triggered by stress and fatigue. The patient had no significant cognitive impairment, had a master's degree in linguistics and was a specialized language teacher. She had a cognitive profile of average-low global efficiency but within the norm.

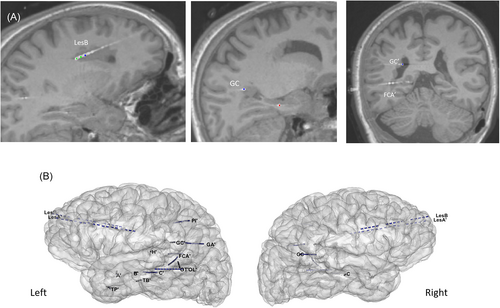

The main hypothesis was of a left temporal lobe organization. SEEG was performed with the main objective of performing RF-TC of the EZ, especially given the multifocal nature of the heterotopic lesions and the reported benefit of RF-TC for this etiology.15 An electrode implantation strategy was defined accordingly (Figure 2) and the SEEG procedure followed previous reported guidelines.2 The whole surgical procedure of depth electrode insertion was performed under general anesthesia with robotic assistance (Rosa; ZimmerBiomet), and intraoperative CT (Airo; Stryker) including the stereotactic frame application. No invasive gesture whatsoever was performed awake. ES was performed with the aim of triggering seizures in epileptogenic sites and functional mapping of language. Two types of stimulation were performed: at low frequency (1 Hz) and high frequency (50 Hz).4 The ES took place in the patient's room, the patient being comfortably installed in her bed and under video-SEEG monitoring. At the end of the SEEG, a session of RF-TC on the selected epileptogenic sites was performed, under video-SEEG monitoring in the patient's room, during wakefulness, according to a procedure described elsewhere16 (Figure 1B).

Regarding past medical and psychiatric history, the patient had previously suffered severe PTSD following a fall on horseback, which required extensive spinal surgeries in 2016 and 2017. These symptoms had previously been successfully treated through EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) therapy with her psychologist, with full recovery. Other than her history of PTSD, she had no known psychiatric disorders at the time of the procedure and was fully informed of the different stages of the SEEG and the different procedures. She gave her consent and was pleased with the treatment.

3 SEEG TRAUMATIC EXPOSURE

3.1 Electrical stimulation and language testing

They deliberately made me unable to answer.

It was degrading, humiliating.

The words were inside my head, my brain for example was formulating ‘plane’, though it was impossible for me to say it out loud, because they were triggering a seizure.

In front of the neurologists and interns, I lost my self-confidence, I felt humiliated.

3.2 SEEG-guided radiofrequency thermocoagulation

Just like that, they roasted my brain, as if it was completely normal.

I have had those neurons in my brain since I was born, they put the electrodes and removed them, just like that.

4 PSYCHO-AFFECTIVE SYMPTOMS POST SEEG

4.1 Posttraumatic stress disorder post SEEG

Following this hospitalization, the patient developed a severe case of PTSD. She developed avoidance behaviors to any stimuli that reminded her of the SEEG. Severe symptoms of traumatic reviviscence were present; she heard the “plok-plok” sound of the RF-TC in her head every night and sometimes during the day, which considerably reduced her sleep. She reported reliving scenes and nightmares of the hospital; the wires of the electrodes, the face of her neurologist who arrived to start the RF-TC and the pain in her skull. She also reported being shocked by a recurring nightmare where she clearly saw the neurosurgeon's floating above her, facing her, in her room with the intense fear that the SEEG would occur again. She over-reacted to any stimuli associated with memories of the SEEG. She also reported having intrusive and uncontrollable flashbacks of images and had highly accurate memory of drawings in the image naming book. All feelings of reviviscence and nightmares were accompanied by the sounds of the RF-TC (“plok-plok”).

4.2 Post SEEG anxio-depressive symptoms and intrusion phobia

The patient reported intense psychological distress, anxiety attacks, and tears almost every day. She reported that she was isolated and had persistent ruminations about her traumatic memories. She also reported having lost interest in activities and relationships, and had insomnia, disordered eating behavior, and reduced libido with fearful reactions to any physical contact.

They took away my epilepsy.

I lost a part of me.

I lost a part of me that defined my identity: the epileptic person.

I don't know how to feel right now, I am lost.

5 CLINICAL PICTURE AND FOLLOW-UP

Based on the history of this case, we report that the patient had psychiatric decompensation resulting from the SEEG, the hospitalization, as well as the examinations associated with this presurgical management: ES and RF-TC. The patient presented a complex clinical picture of PTSD, intrusion phobias, and grief that we associate with forced normalization. It is interesting to identify several factors that increased the risk of decompensation: the patient's psychiatric history, the stress associated with the SEEG and the hospitalization, the absence of emotional and social support at the time of her stay (during a period of restricted visits related to COVID-19 preventative measures), the notable vulnerability of this patient associated with all these factors, and her psycho-affective profile. Among the complex dynamics of all these risk factors, we believe that this strongly increased the shocking and intrusive nature of the stimulations (but not of the seizures provoked by the stimulations) as well as of the sound of the RF-TC, which subsequently triggered the traumatic clinical picture of post SEEG PTSD as well as the psycho-affective and identity consequences, linked to forced normalization. Indeed, perhaps the emptiness associated with the cessation of seizures can explain the clinical picture we have just described. The patient underwent psychological therapy for the PTSD she developed after the SEEG. She was treated with EMDR sessions for her memories related to SEEG hospitalization. At the time of evaluation, she was still undergoing treatment, but she was much better and most of her PTSD symptoms had disappeared. Psychological therapy continues, to address problems of identity and affective aspects related to her epilepsy and the seizures. Despite the psychological repercussions of her experience with the SEEG, the patient does not regret having undergone this procedure.

6 DISCUSSION

Surgeries, and in particular invasive surgeries, such as SEEG, can be psychologically traumatic, but to date there are no studies on the development of PTSD following SEEG, nor recommendations for prevention and management.

During and following the SEEG examination, this patient presented with acute characteristics of PTSD, revealing true psychological damage due to a traumatic invasive and intrusive experience.

The traumagenic characteristic of ES language testing in this case suggests that the ability to speak naturally with intimacy and normal intellectual ability may be abruptly interrupted by electrical stimulation. The RF-TC was experienced as a dramatic and spectacular medical intervention. The perceived seriousness of this situation was further reinforced by the normalized and standardized context of the procedure. Moreover, the patient reported distress following seizure freedom, which we can link to a process of forced normalization,19 which corresponds to the development of psychiatric disturbance following seizure freedom in patients with uncontrolled epilepsy. This abrupt cessation of seizures could be associated in this case with difficulties for the patient to experience a seizure-free lifestyle, which has already been reported.20 Moreover, this aspect was declared by the patient who readily reported a considerable impact of the long-term absence of seizures and psycho-affective, social and identity difficulties. Given the severity of the PTSD developed by the patient and the psycho-affective impact, identifying probable risk factors for the development of such symptoms would appear to be important.

However, it should be noted that she had a prior traumatic history, little emotional support during her stay (due to the physical absence of her relatives) and very little emotional preparation even though she was fully informed about each procedure. We suspect that many risk factors, including not being properly aware of the issues at stake, increase the perception of the RF-TC noise as shocking and dramatic. Moreover, we may also consider involvement of the neurophysiological impact of electrostimulation in brain regions associated with PTSD21 that may have caused the symptoms. Future studies on a larger cohort are necessary to evaluate risk factors, psychiatric consequences, and prevention and management methods.

No risk factors for PTSD have been reported for SEEG, however, some factors have been described for awake surgery, among them: younger age, female gender, admission and length of stay, anxiety during the procedure, fear and psychotic experiences/memories, or the volume and dosage of various medications administered.8-10 Above all, it seems essential to consider the history of prior PTSD in patients who are candidates for SEEG, which could be considered a major risk factor for developing postsurgical PTSD.22, 23 It would be relevant to systematically perform a psychological evaluation before and after surgery. In the preventive evaluation, the systematic use of certain tools, in addition to the interview, can be beneficial; for anxiety, depression, PTSD, but also to develop and validate a more specific questionnaire which is the case for other neurosurgical methods, such as the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Inventory for Awake Surgery Patients (PTSD-ASP).8

It would also seem important to consider relatives' support during hospitalization. We also advocate reinforcing, in the preoperative period, education about the SEEG procedure and neurosurgery, for example, using testimonies of former patients or via the organization of therapeutic groups. In addition, we believe that it is necessary to reinforce psychological care during hospitalization for SEEG; for example, education, psychological support by a psychologist or nurse during invasive examinations, the use of sedative medication, relaxation tools, meditation, or hypnosis.23, 24

7 CONCLUSION

We report, for the first time, a case of post SEEG PTSD, in which psychiatric decompensation symptoms were associated with presurgical management. We strongly believe that it is very important to report other similar cases in order to highlight the potential psychological adverse effects associated with SEEG treatment, ES, and RF-TC. With the aim of systematically considering the psycho-affective aspects of patients undergoing SEEG, it is necessary to develop methods or procedures, which should include screening of vulnerable patients, identification of risk factors, and vigilance of risks of decompensation. In this way, presurgical examinations may be optimized to best preserve the mental health of patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

Test yourself

-

Which part of the SEEG procedure was experienced as being most traumatic by the patient?

- Thermocoagulation

- Language testing

- Cognitive experiment

-

In addition to the classic semiology of PTSD, which specific posttraumatic symptoms were observed in this patient related to the SEEG experience?

- Anomic aphasia

- Intrusion phobia

- Hypervigilance

-

What was the most prominent symptom of PTSD based on the patient's clinical picture after the SEEG?

- Nightmares

- Reliving the sound of the thermocoagulation

- Hospital memories

Answers may be found in the supporting information.