Spontaneous peri-aortic hematoma in a patient with new-onset chest pain

Funding and support: By JACEP Open policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

Supervising Editor: Yiju Teresa Liu, MD, RDMS.

Abstract

Peri-aortic hematoma formation is a common sequela of esophageal rupture and aortic dissection, but non-traumatic spontaneous hematoma formation is an uncommon finding. We present the case of a spontaneous peri-aortic hematoma in a 66-year-old male with associated left atrial thrombus. This 66-year-old male presented to a local emergency department with non-radiating epigastric and mid-sternal chest pain and was found to have a non-traumatic peri-aortic hematoma of unknown etiology that developed over a period of 12 hours. Imaging revealed a newly formed left atrial thrombus causing mass effect on the pulmonary veins and a newly formed left-sided pleural effusion. The patient was subsequently transferred to an outside facility for higher level of care where additional pathological etiologies of hematoma were further excluded. Before discharge, the hematoma spontaneously dissipated and the patient was discharged on oral anticoagulants for treatment of the atrial thrombus and advised to follow-up on an outpatient basis with hematology and cardiology specialists.

1 INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous peri-aortic hematomas are a rare finding among patients presenting with chest pain and generally are not well understood. Most reported cases of posterior mediastinal hematomas are caused by aortic dissection, esophageal rupture, or trauma. Falls, vertebral fractures, and other blunt-force trauma have all been linked to posterior mediastinal hematomas.1 Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) procedures have also been known to cause aortic hematomas up to several weeks after surgery.2 Peri-aortic hematomas most commonly accumulate posterior to the aorta or between the aorta and esophagus and can be confused for other mediastinal pathologies like extranodal lymphoma, esophageal rupture, or other mediastinal masses.2 Advanced imaging, including computed tomography with intravenous contrast, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, and transesophageal echocardiography is necessary in diagnosing and differentiating mediastinal pathology.

1.1 Case

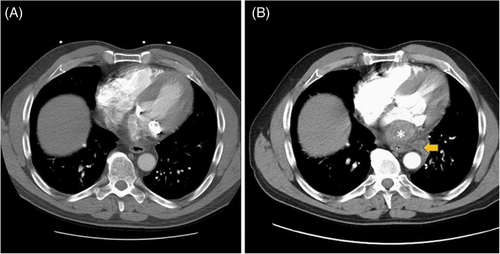

A 66-year-old male patient with a past medical history of hypertension and bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement presented to the emergency department with sudden onset chest pain that started 2 days prior. The patient described the pain as 10/10 in severity, localized to the midsternal and epigastric regions, intermittent in nature, and worsened by leaning forward. He complained of associated and persistent nausea. He denied shortness of breath, diaphoresis, neck, or arm pain. The patient denied a history of prior myocardial infarction or aortic aneurysm but did report having several episodes of amaurosis fugax several years prior for which he was reportedly taking clopidogrel daily. The patient was seen at an associated freestanding emergency department 12 hours before presenting to our emergency department for the same complaint and was discharged home after a negative workup that included an electrocardiogram (ECG) with normal sinus rhythm, negative cardiac troponins, and an unremarkable computed tomography with angiography of the chest (Figure 1A). The patient was discharged home with appropriate return precautions.

The patient presented to our emergency department with worsening pain 12 hours following his initial emergency department visit. On arrival, he appeared in moderate to severe distress and was clutching his chest. He was afebrile, with a heart rate of 90 bpm, respiratory rate of 18 bpm, blood pressure of 148/80 mm Hg, and pulse oximetry of 99% on room air. The remaining physical examination was unremarkable. No murmur or abnormal heart sounds or lung sounds were auscultated on examination. The patient's pain was non-reproducible and did not improve with change in positioning.

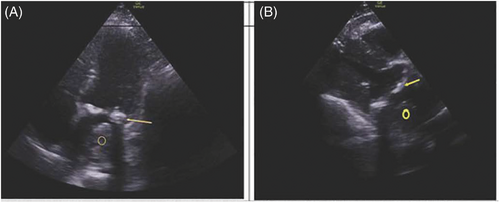

Initial electrocardiogram demonstrated normal sinus rhythm. After administration of a gastrointestinal cocktail, nitroglycerin, and opiates, the patient's chest pain continued to worsen, prompting repeat computed tomography with angiography (CTA) of the chest and abdomen. CTA of the chest revealed a new large left atrial thrombus, approximately 5.4 × 3.7 cm, surrounding the mitral valve and a possible posterior mediastinal, peri-aortic hematoma, 4.7 × 7.6 cm in size, causing mass effect on the left pulmonary veins with associated left pleural effusion (Figure 1B). Laboratory evaluation was remarkable for a high sensitivity troponin 657 ng/L. Point of care echocardiography (Figure 2) confirmed the presence of a large left atrial thrombus with moderate mitral stenosis.

The patient was cared for in the progressive care unit and consults were placed for thoracic surgery and gastroenterology teams. The patient received a second CTA 2 days following admission, which again noted an area in the posterior mediastinum, approximately 5.1 × 2.5 × 5.9 cm in size, consistent with a hematoma. On day 4 of admission, the patient received a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which showed an ill-defined 6.5-cm opacity in the posterior mediastinum abutting the esophagus that was consistent with a mediastinal hematoma. One week after initial diagnosis, the patient was then transferred to an outside hospital for higher level-of-care.

On arrival to the outside facility, the patient was found to be in new-onset atrial flutter with a 4:1 atrioventricular block. Repeat cardiac MRI performed at the outside facility 1 week following the initial diagnosis confirmed a large amount of layering thrombus in the posterior aspect of the left atrium extending into the left lower pulmonary vein, a small left pleural effusion from flow limitation and congestion, moderate to severe mitral stenosis, and mitral annular calcification. Echocardiography showed no evidence of regional wall motion abnormalities with an ejection fraction of 60%–65%, a moderately calcified mitral annulus with moderate regurgitation, and a dilated left atrium with posterior thrombus with increased pulmonary arterial systolic pressure of 50 mm Hg. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan was performed 2 weeks after initial imaging to further assess the etiology of the posterior mediastinal mass versus hematoma, which revealed no evidence of infiltrative mass but did show an area of high attenuation in the posterior mediastinum, likely from a prior dissipating hematoma. Following resolution of the hematoma, the patient converted from atrial flutter to normal sinus rhythm, possibly indicating that the hematoma had caused a mass effect on the cardiac sinus nodes and increased atrial pressures. Coagulopathy workup was negative. The patient was started on oral anticoagulation for the left atrial thrombus that did not resolve and was discharged home with cardiology and hematology follow-up outpatient. No etiology was identified, and at the time of this report, the patient continues to do well without any evident long-term sequelae.

2 DISCUSSION

In the absence of coagulopathy or other significant risk factors for thrombus formation, this patient's degree of mitral stenosis with regurgitation likely played a role in the formation of the left atrial thrombus as a result of sluggish blood flow and flow limitation through the mitral valve. Mitral stenosis has been linked to formation of atrial thrombi.3 Atrial fibrillation is a common cause of atrial thrombi formation, but the patient had no known history of atrial fibrillation or flutter. The new-onset atrial flutter was suspected to be caused by the mass effect of the left atrial thrombus on the pulmonary veins and left atrial dilation rather than an atrial fibrillation induced thrombus formation. Possible etiologies of peri-aortic hematomas include esophageal rupture and acute aortic dissection, both of which were ruled out in this patient on CTA and barium esophagram. The etiology of the patient's peri-aortic hematoma remains unknown and appeared to be spontaneous. Several cases of peri-aortic hematoma following TAVR procedures have been reported up to several weeks following the procedure.2 The patient underwent a TAVR procedure 9 years before presentation, but this was unlikely the etiology for his acute peri-aortic hematoma formation.

The suspected peri-aortic hematoma that was originally seen on CT angiography and initial cardiac MRI without noted confirmation on the second cardiac MRI or transthoracic echocardiogram performed at the outside facility after transfer might raise concern that this was an artifact or misinterpretation. This is unlikely given that a second CT angiography and cardiac MRI performed at our facility before transfer confirmed the presence of a posterior mediastinal hematoma. Three separate and independent reviewing radiologists confirmed the presence of a posterior mediastinal hematoma on two separate CTA studies and cardiac MRI, and the images did not suffer from poor quality acquisition or motion artifact on any of these imaging modalities. The repeat cardiac MRI performed at the outside facility over 1 week after the patient's initial diagnosis and CTA imaging did not note any opacity in the posterior mediastinum, which likely indicates that the hematoma resolved after the patient was transferred.

Presence of a spontaneous peri-aortic hematoma requires prompt and extensive evaluation to distinguish the etiology from that of esophageal rupture or acute aortic dissection induced mediastinal hematomas. On diagnosing unexplained hematomas in the presence of arterial or venous thromboembolic disease, caution should be exercised when prescribing anticoagulants. Anticoagulation was initially withheld in our patient due to concern for life-threatening bleeding and was only started after the patient's peri-aortic hematoma had resolved, as evidenced by PET scan. In patients with arterial or venous thromboembolic disease who do not see prompt resolution of hematoma, inferior vena cava filters may be necessary as an alternative to anticoagulation. Choice of anticoagulation can be tailored to each patient and may include heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, or warfarin.

Prudence is necessary when differentiating spontaneous from pathological mediastinal hematomas to avoid what would likely be catastrophic outcomes resulting from missed hematomas associated with aortic dissections or esophageal ruptures, especially in anticoagulated patients. When diagnosing an undifferentiated peri-aortic hematoma, it is imperative that the appropriate specialties be consulted early in the workup to further delineate the source or nature of the hematoma. In the case presented, cardiothoracic surgery, cardiology, hematology, and gastroenterology co-consulted to rule out life-threatening causes of peri-aortic hematoma. Spontaneous hematomas, as in the case of this patient, may dissipate on their own and will not require further intervention, but should be followed up closely on an outpatient basis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Eric Kalivoda, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, and Amanda Webb McAdams, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine. This research was supported in part by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity (HCA West Florida Division).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.