Impaired dendritic cell differentiation of CD16-positive monocytes in tuberculosis: Role of p38 MAPK

Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the world's most pernicious diseases mainly due to immune evasion strategies displayed by its causative agent Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Blood monocytes (Mos) represent an important source of DCs during chronic infections; consequently, the alteration of their differentiation constitutes an escape mechanism leading to mycobacterial persistence. We evaluated whether the CD16+/CD16− Mo ratio could be associated with the impaired Mo differentiation into DCs found in TB patients. The phenotype and ability to stimulate Mtb-specific memory clones DCs from isolated Mo subsets were assessed. We found that CD16− Mos differentiated into CD1a+DC-SIGNhigh cells achieving an efficient recall response, while CD16+ Mos differentiated into a CD1a−DC-SIGNlow population characterized by a poor mycobacterial Ag-presenting capacity. The high and sustained phosphorylated p38 expression observed in CD16+ Mos was involved in the altered DC profile given that its blockage restored DC phenotype and its activation impaired CD16− Mo differentiation. Furthermore, depletion of CD16+ Mos indeed improved the differentiation of Mos from TB patients toward CD1a+DC-SIGNhigh DCs. Therefore, Mos from TB patients are less prone to differentiate into DCs due to their increased proportion of CD16+ Mos, suggesting that during Mtb infection Mo subsets may have different fates after entering the lungs.

Introduction

Monocytes (Mos) are large circulating leukocytes of the myeloid lineage that mediate essential functions of innate immunity including phagocytosis and cytokine production 1, 2. Mos are produced in the bone marrow and released into the blood, and circulate in blood or reside in a spleen reservoir and, upon tissue infiltration they can differentiate into macrophages (MΦs) or DCs. Although human blood Mos are a highly heterogeneous population, two main subsets have been described: CD14+CD16− “classical” Mos are the major Mo population and CD14+CD16+ Mos, the minor one (5–10% of total Mos). The latter subset has a more mature phenotype and an enhanced proinflammatory activity 3. This heterogeneity has led to the hypothesis that Mos are committed to specific functions prior to tissue infiltration 4. Also, an imbalance in the relative proportions of the subsets during acute inflammation 5 and several infectious diseases 6-10 including tuberculosis (TB) 11, 12 has been described. TB, a disease that mainly affects the respiratory system, infects one-third of the world's population and kills 2 million people each year 13. The success of infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent, depends mainly on its ability to elude host immune responses 14. As DCs contribute to the development of protective immunity it is reasonable to wonder whether Mtb may interfere in DCs generation, leading to immune evasion. Considering that Mos represent an important source of APCs in chronic infections, these precursors could be hampered in their ability to differentiate toward DCs as a consequence of Mtb infection. 15, 16. This escape mechanism becomes relevant given that the major DCs subset involved in mycobacterial infections are considered to be Mos-derived DCs or “inflammatory DCs” 17, 18. In fact, the remarkable developmental plasticity of Mos allows them to differentiate into diverse DC populations, and multiple local mediators resulting from inflammatory and infectious processes can modulate their differentiation 19. Mtb has been extensively described to be able to impair Mo differentiation as an escape mechanism, contributing to mycobacterial intracellular persistence 20, 21. Indeed, it has been reported that Mtb is able to affect Mo differentiation in lung tissue 22, therefore the modulation of DC generation by Mtb may result in different physiopathological outcomes of the infection. Furthermore, a decreased number of circulating DCs has been reported in pulmonary TB patients 23.

The acquisition of CD1 molecules and DC-specific inter-cellular adhesion molecule-3-Grabbing Nonintegrin (DC-SIGN) is a hallmark of in vitro DC differentiation. Furthermore, these two receptors are particularly relevant in the immune response to Mtb. On one hand, Mtb has a high content of antigenic lipids, which can be presented to CD1-restricted lipid-specific T lymphocytes 24, and on the other hand, DC-SIGN has been described as the main Mtb receptor on human DCs 25. We have previously demonstrated that Mos from healthy subjects (HSs) exposed to IL-4 and GM-CSF generate mainly CD1a+CD14−DC-SIGNhighCD86low DCs, which are efficient APCs for Mtb-specific T cells, while Mos from TB patients fail to differentiate into DCs generating a CD1a−CD14+DC-SIGNlowCD86high cell population 21, which induces a low specific T-cell proliferation in response to Mtb 26. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the circulating CD16+ Mo subset is increased in TB patients 11, 12.

In this study, we evaluated whether the imbalance in the relative proportion of the Mo subsets in TB patients could explain the altered differentiation toward DCs in terms of CD1 molecules and DC-SIGN expression. Our results show that altered CD1a−DC-SIGNlow DCs are generated from CD16+ Mos, which are enriched in TB patients, involving a sustained p38 MAPK activity during their differentiation process. Thus, the balance between Mo subsets may be an important determinant of the differentiation of these Mo subsets, and the outcome of Mtb infection.

Results

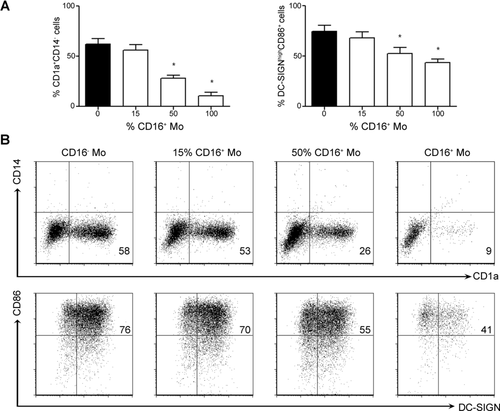

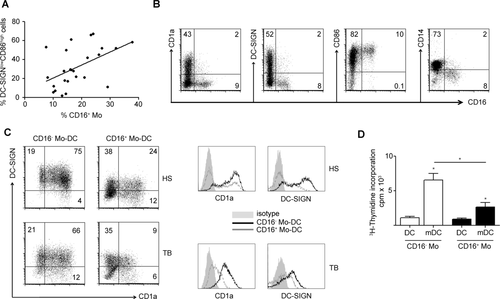

CD16+ Mos give rise to CD1a−DC-SIGNlow population

We compared the ability of each Mo subset from HSs to generate DCs in vitro. CD16+ Mos were isolated by positive selection based on their CD16 expression and then differentiated in presence of GM-CSF and IL-4. This isolation method is extensively employed 27, 28, even though, it has been reported that the use of xenogeneic Abs could alter/activate Mos 29. In this regard, FcγRIII (CD16 receptor) unlike FcγRI or FcγRII cross-linking, has not been associated to an impairment of DCs differentiation 30. Interestingly, we found that the CD16+ Mo subset gave rise to a major CD1a−DC-SIGNlow (CD16+ Mo-DC) population, while the CD16− Mo subset gave rise to a main CD1a+DC-SIGNhigh (CD16− Mo-DC) population (Fig. 1). In agreement with that, the higher the percentage of CD16+ Mos, the larger the CD1a−DC-SIGNlow cell population generated (Fig. 1).

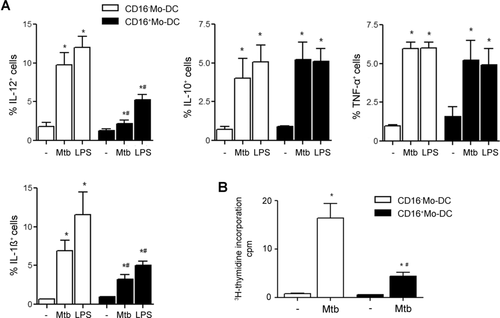

Thereafter, we compared the cytokine profile and the specific lymphocyte proliferation induced by CD16− Mo-DCs and CD16+ Mo-DCs upon Mtb maturation. Lower percentages of IL-12+ and IL-1β+ cells were found in Mtb- and LPS-matured CD16+ Mo-DCs than in CD16− Mo-DCs, while IL-10 and TNF-α levels were similar (Fig. 2A). Besides, CD16+ Mo-DCs from tuberculin skin test positive (TST+) HSs were less efficient in inducing the proliferation of memory clones against Mtb (Fig. 2B).

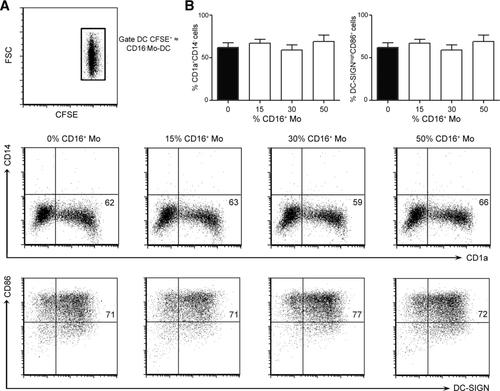

CD16+ Mos do not induce a bystander effect on the differentiation of CD16− Mos

So far, we demonstrated that under in vitro conditions, CD16+ Mos are less prone to differentiate into DCs. Besides, we wondered whether CD16+ Mos were able to affect CD16− Mo differentiation. To test it, CD16− Mos were labeled with CFSE while CD16+ Mos remained unstained, then CFSE-labeled CD16− Mos were cocultured with different amounts of unlabeled CD16+ Mos to trace their phenotype throughout the differentiation process. We found that CD16+ Mos did not modify the differentiation of CD16− Mos in terms of CD1a/CD14 and DC-SIGN/CD86 expression (Fig. 3). This result indicates that CD16+ Mos are intrinsically less prone to give rise to CD1a+DC-SIGNhigh DCs and that they do not induce a bystander effect either by direct contact or by the secretion of soluble factors.

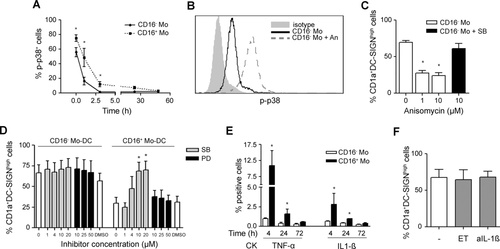

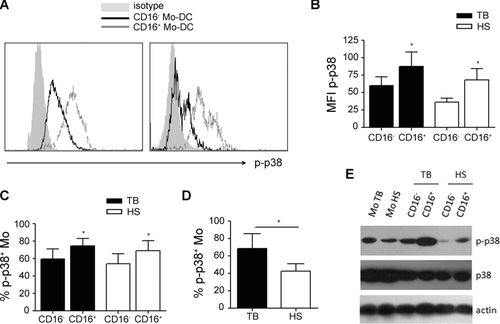

The enhanced p38 signaling cascade is involved in the impaired differentiation of CD16+ Mos

It has been described that the activation of p38 MAPK is detrimental to the differentiation of immature DCs from Mos and that a successful differentiation process requires the progressive downregulation of phosphorylated (p)-p38 levels 31, so we studied the kinetics of p-p38 expression along the differentiation process of CD16− Mos and CD16+ Mos from HSs. As it is shown in Figure 4A, CD16+ Mos displayed higher percentages of p-p38+ cells from the onset of the culture and the downregulation of p-p38 in response to GM-CSF and IL-4 was delayed in CD16+ Mos compared with CD16− Mos. In fact, p-p38 expression in CD16+ Mos was efficiently downregulated only after 24 h of culture. To confirm the role of p38 MAPK in DCs differentiation, CD16− Mos were activated with anisomycin, a well-characterized and relatively specific activator of p38 32, within the first 30 min of the differentiation process. To avoid the induction of apoptosis, anisomycin was used at low doses (1–10 μM). As it is shown in Figure 4B, a clear upregulation of p-p38 was observed in anisomycin-treated CD16− Mos, being this early event enough to impair the subsequent acquisition of CD1a and DC-SIGN molecules at day 6 of culture (Fig. 4C). Also, the phenotype of anysomicin-treated CD16− Mo-DCs could be restored by the addition of SB220025 (SB), the inhibitor of p38 activity (Fig. 4C).

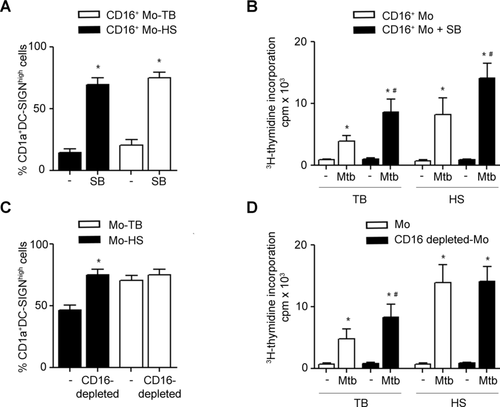

Next, we wondered whether the blockage of p38 activity in CD16+ Mos could restore their differentiation fate. In this regard, while the inhibition of p38 restored the expression of CD1a and DC-SIGN from CD16+ Mo-DCs in a dose dependent and specific manner, the addition of the ERK inhibitor (PD) did not modify the phenotype (Fig. 4D). Finally, the preincubation of CD16− Mos with SB did not affect their capacity to give rise to CD1a+DC-SIGNhigh DCs (Fig. 4D), which is in agreement with their proper p-p38 downregulation along the culture (Fig. 4A).

Considering that the production of inflammatory cytokines in Mos, such as IL-1ß and TNF-α, is highly dependent on the activation of p38 MAPK pathway 33, we wondered whether different patterns of these cytokines could be found in CD16+ and in CD16− Mos along the differentiation process. Thus, intracellular expression of TNF-α and IL-1β was evaluated at different time points in CD16− Mos and CD16+ Mos cultured with IL-4 and GM-CSF. Accordingly with its higher p-p38 activity, higher frequencies of TNF-α+ and IL-1β+ cells were found in CD16+ Mos within the first 24 h of culture (Fig. 4E) suggesting that CD16+ Mos represent a more activated cellular status than CD16− Mos. Furthermore, IL-1β and TNF-α production was downregulated along the culture in both Mo subsets in response to IL-4 and GM-CSF as has been previously described 34. Finally, the addition of the TNF-α (etanercept) antagonist or of neutralizing Abs against IL-1β did not improve CD16+ Mos differentiation in terms of CD1a/DC-SIGN expression (Fig. 4F). Hence, the low basal production of at least IL-1ß and TNF-α by CD16+ Mos could not explain the altered differentiation toward DCs. Considering that the p38 MAPK pathway has been shown to regulate also IL-10 expression in the human monocytic cell line THP-1 35, we evaluated IL-10 production by CD16− and CD16+ Mos along the differentiation process. In this regard, we found nondetectable IL-10 levels either by flow cytometry or by ELISA and consequently, the addition of anti-IL-10 neutralizing Abs did not restore the phenotype of CD16+ Mo-DCs (Supporting Information Fig. 1). Thus, IL-10 may not be relevant in the altered differentiation of CD16+ Mos into DCs.

Impact of the abundance of CD16+ Mos on DC differentiation in TB

Since peripheral Mos from TB patients displayed a shift toward the CD16+ Mo subset 12 and failed to differentiate into CD1a+DC-SIGNhigh DCs 21, we wondered if the imbalance of Mo subsets could be associated to the altered DC phenotype observed in TB patients. As it is shown in Figure 5A, the percentages of CD16+ Mos from TB patients correlated moderately with the percentages of the altered DC-SIGNlowCD86high DC population (p < 0.05, n = 25). Then, we evaluated the acquisition of some robust DC phenotype markers, which are indeed relevant in Mtb infection, such as CD1a and DC-SIGN, in CD16+ Mos from TB patients during their differentiation. This analysis was performed at 20 h from the onset of the differentiation given that CD16 expression is downregulated later on (data not shown). We observed that CD16+ Mos were unable to upregulate CD1a and DC-SIGN showing a high CD86 and a low CD14 expression (Fig. 5B). As CD16 expression is downregulated during the differentiation toward DCs, we cannot rule out that CD16+ precursors acquire CD1a and DC-SIGN at the same time that they lose CD16 expression. Thus, differentiation assays were performed by culturing isolated Mo subsets from TB patients with GM-CSF and IL-4 for 6 days and their phenotype was determined. As well as for HSs, CD16+ Mo-DCs from TB patients displayed lower percentages of CD1a+DC-SIGNhigh cells (Fig. 5C) and were less efficient in inducing the proliferation of memory clones against Mtb than CD16− Mo-DCs (Fig. 5D).

The activation of p38 signaling pathway in CD16+ Mos from TB patients

First, we compared the basal activity of p38 in both Mo subsets and observed that CD16+ Mos from TB patients or HSs showed higher p-p38 levels than CD16− Mos (Fig. 6A–C and E). Regarding nonphosphorylated p38 levels no differences were found (Fig. 6E). Moreover, Mos from TB patients showed higher percentage of p-p38+ cells than Mos from HSs (Fig. 6D), which is in agreement with their major CD16+ Mos proportion. In fact, the inhibition of p38 activity improved the phenotype (Fig. 7A) and the specific lymphocyte proliferation displayed by CD16+ Mo-DCs from TB and TST+ HSs (Fig. 7B). Finally, to get further insight into the contribution of CD16+ precursors to the altered CD1a−DC-SIGNlow profile observed in DCs derived from TB patients, we evaluated whether the depletion of this subset could modify the resulting DC phenotype and function. Indeed, CD16 depleted-Mos from TB patients gave rise to higher percentages of CD1a+DC-SIGNhigh cells than nondepleted Mos (Fig. 7C). Moreover, DCs derived from CD16+ depleted-Mos induced higher specific T-cell proliferation levels than those derived from nondepleted Mos (Fig. 7D). It is interesting to note that CD16+ Mos from HSs were functionally comparable to TB (Fig. 7A and B) but their depletion did not bring on an appreciable impairment of DCs generation (Fig. 7B and D), probably because they represent less than 15% of total Mos in HSs 12. This result is in agreement with the result from Fig. 1 which showed that the addition of even 15% of CD16+ Mos was not enough to alter significantly the DCs phenotype. Thus, the depletion of CD16+ Mo subset improves the altered differentiation toward DCs observed in Mos from TB.

Discussion

Mos can undergo different activation programs that ultimately define their functional properties including the clearance of dead cells and pathogens, tissue repair and remodeling, and the regulation of inflammatory and immune responses 19. In this study, we demonstrated that CD16+ Mos could not be directed to a DC phenotype in the presence of IL-4 and GM-CSF, and that the expansion of the CD16+ Mo subset in peripheral blood from TB patients was associated with the impairment of DC generation.

In our hands, CD16− Mos were able to differentiate into CD1a+DC-SIGNhighCD86low DCs, while CD16+ Mos differentiated mainly into a CD1a−DC-SIGNlowCD86high DC population which induced a low Mtb-specific lymphocyte proliferation. In agreement with our results, it has been described that LPS-matured CD16+ Mo-DCs secreted low amounts of IL-12 27, suggesting that CD16+ Mo-DCs could represent an important population of regulatory DCs 28. We also showed that matured CD16+ Mo-DCs displayed low levels of IL-1β production while IL-10 or TNF-α production did not differed between subsets. Interestingly, since IL-1β has been described as an IL-12-inducing agent on human Mo-DCs 36, the reduction of IL-1β+ cells observed in CD16+ Mo-DCs could be associated with the low levels of IL-12+ cells.

As TB patients have a high percentage of circulating CD16+ Mos 11, 12, this dichotomy in the differentiation fate of Mo subsets can explain the impairment observed in Mo-derived DCs from TB patients 21. In addition, we observed that CD16+ depletion in Mos from TB patients improved the differentiation toward DCs and that the addition of CD16+ Mos impaired the differentiation of Mos from HSs. So, it could be possible that the CD16+ subset alters the CD16− Mos differentiation. To evaluate this hypothesis, differentially labeled Mo subsets were cocultured to trace the fate of CD16− Mos in terms of CD1a/CD14 and DC-SIGN/CD86. As CD16+ Mos were not able to impair CD16− Mo differentiation toward DCs, we conclude that the CD16+ Mo subset is intrinsically less prone to differentiate into DCs without inducing a bystander effect on the differentiation of CD16− Mos.

In this study, we focused on DC-SIGN expression because it is the main Mtb-receptor in DCs 25 and its activation can modulate the immune response 37. Therefore, given that DC-SIGN together with CD1 molecules are crucial for mounting a protective antimycobacterial response, we considered their acquisition as a hallmark of in vitro Mos differentiation into DCs. Herein, we described for the first time a differential DC-SIGN expression on DCs derived from each Mo subset, showing CD16+ Mo-DCs lower levels than CD16− Mo-DCs. Regarding CD1 molecules expression, it has been established that CD1a expression is lower on DCs derived from CD16+ Mos than from CD16− Mos 27, 28, which is in agreement with our results. Nevertheless, it has been reported that CD16+ Mos are more prone to differentiate into DCs 27, 38, 39, which is in contrast to our results and to the extensive literature that associates CD16+ Mos with a MΦ-like phenotype 40-42. In fact, human CD16+ Mos were phenotypically related to pulmonary alveolar MΦs and some authors have speculated a commitment of these circulating Mos to migrate to the lung 40. Differences between our findings and previously published results may stem from differences among the experimental designs. In particular, Randolph et al. 39 generated DCs after Mos migration through an endothelial barrier in the absence of exogenous cytokine; while in the other studies GM-CSF and IL-4 have been employed with the addition of TNF-α 27 or IL-10 38 to achieve Mos differentiation into DC-like cells. Regarding the physiological relevance of our study, our findings are in agreement with a recent report that determined the role of Mo subsets in an in vivo model by transferring isolated human Mos into the inflamed peritoneum of immunodeficient mice 42. In this model, developing CD16+ Mos displayed poor APC abilities corresponding to MΦ precursors in contrast to CD16− Mos, which became DCs. Accordingly, APCs derived from CD16− Mos would be preferentially involved in activating the adaptive immune response, while APCs derived from CD16+ Mos might act in an immediate innate immune response. This immediate response mediated by CD16+ Mos may be favored by their preferential accumulation in the marginal pool, which facilitates their rapid extravasation into inflammatory sites 43. Also, their enhanced capacity for the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, could be related with an activation program to the detriment of a differentiation one.

Herein we also observed that even at early stages of the differentiation process, CD16+ Mos from HSs were unable to upregulate CD1a and DC-SIGN expression but they conserved a higher CD86 and a lower CD14 expression than CD16− Mos. Hence, although the differences in CD86 and CD14 expression between Mo subsets were conserved as on freshly isolated Mo subsets 44, de novo acquisition of CD1a and DC-SIGN expression was altered during Mos differentiation toward DCs in the CD16+ subset. Besides, CD16+ Mos were more prone than CD16− Mos to undergo spontaneous cell death throughout the differentiation toward DCs, given that fewer numbers of DCs derived from CD16+ Mos were systematically recovered (Supporting Information Fig. 2); thereby the numbers of DCs derived from both Mo subsets were adjusted for functional analysis. This higher tendency of the CD16+ Mo subset to cell death has also been observed when CD16+ Mos were differentiated into MΦs 45, and supports our conclusion that CD16+ Mos have a more activated phenotype.

The relevance of the lack of CD1 molecules displayed by DCs derived from CD16+ Mos was supported by the association between the lower CD1b expression on DCs with their declined ability to present Mtb Ags 21. In this line, it has been demonstrated that CD1-restricted T cells are expanded in TST+ HSs and that CD1-restricted T-cell responses are absent or drastically reduced in TB patients 46, indicating an helpful role of CD1 molecules during Mtb infection. In agreement, as DCs from TB patients showed lower CD1 molecules levels 21, they induced poorer specific proliferation than DCs from TST+ HSs. In addition, we found that the depletion of CD16+ Mos generated DCs with a higher CD1a/CD1b content and an enhanced recall proliferation. In contrast to our results, it has been showed that DCs derived from CD16+ Mos drove a stronger T-cell recall proliferative response against the purified protein derivative of tuberculin than DCs derived from CD16− Mos 47. This difference may be ascribed to the nature of the Ag, while we employed the whole bacteria that include proteins and glycolipids; purified protein derivative of tuberculin is a mixture of secreted proteins that does not require the CD1 molecules-mediated Ag presentation.

It has been previously reported that CD16+ and CD16− Mos can activate distinct signaling pathways 48 and that p38 activity is detrimental for the differentiation of Mos into DCs 31. In this regard, we showed that p38 activity was indeed increased in CD16+ Mos compared with that in CD16− Mos. Consistently, Mos from TB patients, which are characterized by enrichment in CD16+ Mos, displayed higher p-p38 levels than Mos from HSs and its inhibition improved the numbers of CD1a+DC-SIGN+ cells and the Mtb-specific cell response of DCs derived from CD16+ Mos. Hence, p38 activity seems to be responsible for the impairment of the differentiation toward DCs. It is currently accepted that different Mo subsets may reflect developmental stages with distinct physiological functions 4 and that the CD16+ Mo subset constitutes a more mature form of the CD16− subset 49; thereby, the higher p38 activity in CD16+ Mos may contribute to their higher activation degree. In this regard, we suggest that CD16+ Mos are less prone to differentiate to DCs as a result of their more advanced commitment for a specific function compared with CD16− Mos accordingly to their more activated phenotype 12.

The differential capacity of Mo subsets to give rise to APCs populations has been reported in mice where two major populations have been identified on the basis of Ly6C and CX3CR1 expression 50. In particular, it is known that in lungs DCs develop from both Ly6Chigh and Ly6Clow Mos, while MΦs originate from Ly6Clow Mos, which resemble the human CD16+ subset 41. Despite this, whether the differentiation fates described in mice Mo subsets resemble the ones in humans remains unknown. In this sense, it has been recently proposed that both human CD14+CD16− and CD14+CD16+ Mos have inflammatory properties reminiscent of the murine Ly-6Chigh Mos, while CD14dimCD16+ Mos display patrolling properties similar to Ly-6Clow Mos 51, though in this study their preferential differentiation pathways have not been compared.

Taking into account that the differentiation into DC from circulating Mos occurs in vivo 52, 53 and that DCs derived from Mos constitute the major DC subset involved in mycobacterial infections 17, 18, 54, our findings may be relevant to understand the DC deficiencies observed in patients with active TB 23, 55, 56. Furthermore, our results could be also relevant in other diseases characterized by high CD16+ Mo numbers, such as HIV, rheumatoid arthritis, sepsis, atherosclerosis, Kawasaki disease, and hemolytic uremic syndrome, among others 57. If CD16−/CD16+ Mo ratio remains at normal levels, the impact of CD16+ Mos is negligible but under certain pathological conditions — characterized by more than 15% CD16+ Mos — their contribution has a major effect on total DCs population function.

In summary, we found that Mos from TB patients are less prone to differentiate to DCs in vitro due to their increased proportion of the CD16+ Mo subset. These data support the idea that during Mtb infection blood Mo subsets may be committed for precise fates once they have entered into the lungs contributing differentially to TB progression.

Materials and methods

Patients and healthy blood donors

TB patients were diagnosed at the Servicio de Tisioneumonología, Hospital F. J. Muñiz (Buenos Aires, Argentina) by the presence of recent clinical respiratory symptoms, abnormal chest radiography, and positive sputum smear test for acid-fast bacilli. Written, informed consent was obtained according to Ethics Committee from the Hospital Institutional Ethics Review Committee. Exclusion criteria included a positive HIV test and the presence of concurrent infectious diseases or noninfectious conditions (cancer, diabetes, or steroid therapy). Blood samples were collected at 3–10 days after treatment was started. All tuberculous patients (n = 25, average age = 31 years of age, range = 19–52 years of age, 75% male) had pulmonary TB. HSs samples were obtained from the Blood Transfusion Service, Hospital Fernandez, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Buffy coats were employed to obtain sufficient amounts of CD16+ Mos while direct venipuncture samples from HSs TST+ (n = 10, average age: 43 years of age, range: 25–57 years of age; 70% male) were used to compare results with TB patients. All HSs have been vaccinated with bacillus Calmette-Guerin in childhood.

Ags and reagents

The γ-irradiated Mtb H37Rv strain was kindly provided by J. Belisle (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA). Mycobacteria were suspended in free pyrogen PBS, sonicated and adjusted at a concentration of ≈1 × 108 bacteria/mL (OD600 = 1). LPS from Escherichia coli and recombinant human GM-CSF were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Recombinant human IL-4 was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). The following FITC, PE, and/or PerCP/Cy5.5 mAbs against CD14, CD86, IL-10, IL-6 (BD Biosciences), CD16, CD1a, IL-12, TNF-α, IL-1ß (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), CD1b (Ancell Bayport, MN, USA), DC-SIGN (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA); p-p38 (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and isotype-matched mAbs were used in immunofluorescence analysis. For inhibition studies, PD98059 (MEK1 inhibitor) or SB220025 (MAPK14-a and -b inhibitor) from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA) were employed. For activation of kinase cascades, anisomycin (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA) was employed. For cytokines inhibition assays, neutralizing purified Ab against human IL-1β from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA, USA) and etanercept (Enbrel®), the TNF-α antagonist from Wyeth (Buenos Aires, Argentina) were employed.

Mos purification and Mo subsets isolation

Peripheral blood was dispensed into 50 mL polystyrene tubes (Corning, NY, USA) containing heparin. Mos were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) followed by Percoll density-gradient centrifugations and suspended in RPMI 1640 tissue culture medium (Gibco, NY, USA) containing gentamycin (85 μg/mL; Gibco), penicillin (100 U/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% heat inactivated FCS (Gibco; complete medium). Purity and viability were tested using Trypan-Blue exclusion dye. When mentioned, Mo subsets were magnetically labeled with specific microbeads and separated over a MACS Column according to manufacturer's instructions using the CD16+ Monocyte Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Typical procedure yielded less than 15% of CD16− cells in CD16+ Mo fraction.

Mos staining

The CD16− Mo subset was incubated with 5 μM CFSE (Invitrogen, OR, USA) in PBS with BSA 0.1% for 30 min at 37°C. Then, cells were washed and further incubated in complete medium two times at 37°C for additional 10 min.

Mos differentiation

Mos or isolated Mo subsets were cultured in vitro in complete medium in the presence of IL-4 (10 ng/mL) and GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 6 days as previously described 21. When indicated, growing amounts of CD16+ Mos were added to labeled or unlabeled CD16− Mos at the beginning of the differentiation process. In some experiments, Mos were preincubated with different concentrations of SB220025 or PD98059, or same volume of DMSO for 40 min prior to addition of IL-4 and GM-CSF. When indicated, CD16− Mos were preincubated for 30 min with different concentrations of anisomycin. In some experiments, CD16+ Mos were incubated within the first day of differentiation with etanercept (1 μg/mL), or with neutralizing Ab anti-IL-1β (2 μg/mL).

DC maturation

CD16− or CD16+ Mo-DCs were washed and seeded in 24-well plates (Corning) at 1.106 DC/mL in RPMI-1640 supplemented with penicillin–streptomycin and 10% FCS, and cellular maturation was achieved by treatment with Mtb (2 × 106 bacilli/mL) or with LPS (10 ng/mL) for 24 h at 37°C. Cells were centrifuged at low speed for 10 min to selectively spin down cells while extracellular bacteria remain in the supernatant. Thereafter, cells were washed three times and their intracellular cytokine production was determined by flow cytometry. Alternatively, Mtb-matured CD16− or CD16+ Mo-DCs were used for proliferation assays.

Proliferation assays

Specific lymphocyte proliferations (recall) were carried out by coculturing 1 × 104 matured DCs with 1 × 105 autologous lymphocytes from TST+ HSs in round bottom 96-well culture plates (Corning) for 5 days. After that, 0.5 μCi/well of methyl-3H-thymidine (PerkinElmer, MA, USA) was added for the last 18 h and radioactivity was measured in a liquid scintillation counter. The results were expressed as cpm induced by matured or nonmatured DCs.

Immunofluorescence analysis

For surface staining, 0.1–1.106 freshly isolated or differentiated Mos were incubated for 20 min at 4°C with adequate amount and combinations of labeled mAbs in ∼50 μL volume of PBS 1% FCS. Stained cells were washed and suspended in Isoflow (BD Biosciences) for acquisition. For p-p38 level determination, after surface staining as indicated above, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and washed. Then, cells were permeabilized with 500 μL of Perm2 (BD Biosciences) for 15 min and stained with FITC-labeled anti-p-p38 (Santa Cruz) in PBS 1% BSA, washed twice, and analyzed. Prior to intracellular cytokine staining, Brefeldin A (5 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) was added for the last 4 h of culture to block cytokine secretion. Then cells were fixed and permeabilized according to the manufacturer's instructions (Perm2, BD Biosciences) before FITC-anti-IL-6, FITC-anti-IL-10 (BD Biosciences), PE-anti-IL-1ß, FITC-anti-TNF-α, PE-anti-IL12 (eBioscience), or the corresponding isotypes were added. Data acquisition (≈5 × 105 events) was carried out using a FACScalibur flow cytometer equipped with CellQuest software 58. DC or Mo populations were gated according to its forward and side scatter proprieties. The percentage of positive cells and the MFI was analyzed using FCS Express V3 software (De Novo SoftwareTM, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

Western blot analysis

Mo subsets (2 × 106) were dissolved in sample buffer (2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, and trace amounts of bromophenol blue dye in 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8), heated for 5 min at 95°C, and stored at −70°C until subjected to gel electrophoresis. After SDS-PAGE, proteins were electrotransferred from the gel to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) for 2 h and then blocked in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 5% nonfat milk. The membranes were immunoblotted with the indicated Abs overnight at 4°C. After washing, bound Abs were visualized with HRP-conjugated Abs against rabbit or mouse immunoglobulin G 59 by using the ECL Western Blotting System (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany). The following primary Abs were used: rabbit monoclonal anti-p-p38 (Santa Cruz), rabbit monoclonal p38 MAPK (MAPK14) Ab (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA), and mouse polyclonal anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling). The secondary Abs included HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling) or anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling).

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of paired CD16− Mo and CD16+ Mo samples or paired treatments within an Mo subset were performed using the Wilcoxon (nonparametric) paired test. Comparisons of nonpaired data (i.e., normal versus patient's data) were performed by Mann–Whitney (nonparametric) unpaired test. Pearson correlation was used for correlation analysis. All statistical analyses were two-sided, and the significance level adopted was p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank staff of División de Tisioneumonología, Hospital F. J. Muñiz for their great help in providing samples and clinical data. We also thank the Blood Transfusion Service of the Hospital Fernandez for healthy donors recruitment. Specially, we thank Dr. Gabriela Salamone and Dr. Mónica Vermeulen for their great help with Western blot assays. This work was supported by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica [PAE-PICT 2328, PAE-PICT 2329, PICT 2010-059]; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones científicas y Técnicas [PIP 112-2008-01-01476]; and Fundación Alberto J. Roemmers.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

Abbreviations

-

- HS

-

- healthy subject

-

- mDC

-

- matured DC

-

- Mo

-

- monocyte

-

- Mtb

-

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

-

- SB

-

- SB220025

-

- TB

-

- tuberculosis

-

- TST

-

- tuberculin skin test