Comparison of the clinical outcome of different beta-blockers in heart failure patients: a retrospective nationwide cohort study

Abstract

Aim

To compare survival on different beta-blockers in heart failure.

Methods and results

We identified all Danish patients ≥35 years of age who were hospitalized with a first admission for heart failure and who initiated treatment with a beta-blocker within 60 days of discharge. The study period was 1995–2011. The main outcome was all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization. Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare survival. The study included 58 634 patients of whom 30.121 (51.4%) died and 46.990 (80.1%) were hospitalized during follow-up. The mean follow-up time was 4.1 years. In an unadjusted model carvedilol was associated with a lower mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 0.737, 0.714–0.761] compared with metoprolol (reference) while bisoprolol was not associated with an increased mortality (HR 1.020, 0.973–1.069). In a model adjusted for possible confounders and stratified according to beta-blocker dosages, patients that received high-dose carvedilol (≥50 mg daily) had a lower all-cause mortality risk (HR 0.873, 0.789–0.966) than patients receiving high-dose (≥200 mg daily) metoprolol (reference). High-dose bisoprolol (≥10 mg daily) was associated with a greater risk of death (HR 1.125, 1.004–1.261). High-dose carvedilol was associated with significantly lower all-cause hospitalization risk (HR 0.842, 0.774–0.915) than high-dose metoprolol (reference), while high-dose bisoprolol had insignificantly lower risk than high-dose metoprolol (HR 0.948, 0.850–1.057).

Conclusions

Heart failure patients receiving high-dose carvedilol (≥50 mg daily) showed significantly lower all-cause mortality risk and hospitalization risk, compared with other beta-blockers.

Introduction

Randomized clinical trials have shown that bisoprolol, carvedilol and metoprolol improve survival and reduce hospitalizations for cardiac events in patients with chronic heart failure.1-6 The comparison of carvedilol and metoprolol on clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure in the Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial (COMET) from 2003 is the only randomized clinical trial to have compared beta-blockers head to head.7 This study demonstrated that carvedilol had a significant beneficial effect on all-cause mortality compared with metoprolol. The validity of the COMET results has since been discussed on the basis of the compared dosage regimens and formulation of metoprolol chosen for the study.8-12 Observational studies have compared different beta-blockers in heart failure patients but their conclusions have not been consistent. A Canadian observational study of 26 787 patients diagnosed with heart failure found no difference in mortality rates among patients receiving metoprolol or carvedilol.13 Another study from 2008 of 26 112 north American veterans, found the controlled release formulation of metoprolol to be superior in improving survival compared with carvedilol.14 In contrast, another observational study from 2005, based on a health-insurance claims database in the USA, which compared metoprolol tartrate and carvedilol, found carvedilol to be superior in terms of mortality and hospitalizations.15 Equal benefit of metoprolol and carvedilol was the result of a third US observational study.16 A small Japanese study found no difference in survival between bisoprolol and carvedilol.17 These studies were done on varying small patient populations and as single-centre or single-region studies. Owing to the inconsistent results from these studies we saw a need for more and larger studies. Based on extensive Danish nationwide patient and medicinal product dispensing registries this study's aim was to compare short- and long-term treatment with several beta-blockers in heart failure patients, examining type of beta-blocker as well as dose.

Method

Patient population

Using the Danish National Patient Registry we identified all patients aged ≥35 years who were discharged after a first-time hospitalization for chronic heart failure. Patients were included from the first date on which one of the following diagnosis codes appeared in the registry [International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD10), codes I50 (heart failure), I42 (cardiomyopathy), I110 (Hypertensive heart disease with (congestive) heart failure) and J81 (Pulmonary oedema)], between 1978 and 31. December 2011. The registry contains records of all hospitalizations and primary and secondary diagnosis in Denmark since 1978.

Using The Danish Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics, we included patients who claimed at least one outpatient prescription of a beta-blocker of any sort (ATC code C07) 60 days following discharge. Patients who claimed their first beta-blocker prescription later than 60 days were excluded. The registry contains data on all prescriptions dispensed in Denmark since 1995, including medicine strength, quantity dispensed and dispensing date. Heart failure patients diagnosed before the initiation date of this registry were excluded.

We obtained the vital status of each patient as of 31 December 2011 (the date of last data sample) via the Central Population Registry of Denmark. This registry includes data on every citizen of Denmark based on a personal social security number. This allows us to connect the data of all the registries via individual-level linkage.

Pharmacotherapy, exposure groups and dosages

Patients were categorized into exposure groups according to the beta-blocker claimed from their first prescription after discharge: metoprolol, carvedilol, bisoprolol or other. Daily dosages were estimated as described previously.18 For each of the beta-blockers, metoprolol, carvedilol, and bisoprolol we defined a minimum and a maximum possible daily dosage for each tablet strength available for prescription. Usually, we used half a tablet as minimum and two tablets as maximum. Based on the date, strength, and quantity of tablets dispensed by each prescription, and taking into account up to seven consecutive prescriptions, we assumed a continuous treatment period, if the defined minimum daily dosage for each tablet strength could ensure continuous treatment. Daily dose during continuous treatment was calculated as the mean dose for each patient.

Based on the heart failure treatment guidelines19 we stratified exposure groups metoprolol, carvedilol and bisoprolol into three strata (low, intermediate, and high daily dosage) according to each patient's estimated daily dosage, at 3 months, 6 months, and 2 years of treatment. For metoprolol the dosages used were ≤100 mg/day (low), 101–199 mg/day (intermediate) and ≥200 mg/day (high). For carvedilol the dosages used were ≤12.5 mg (low), 12.6–49.9 mg (intermediate) and ≥50 mg (high) and for bisoprolol the dosages used were ≤5 mg (low), 6–9 mg (intermediate) and ≥10 mg (high).

We assessed whether patients had received any beta-blocker treatment before their index hospitalization and whether they switched type of beta-blocker throughout their treatment period.

The year of first beta-blocker prescription after index hospitalization for all patients was divided into periods of before 2001, from and including 2001–2005 and from and including 2006–2011.

Persistence of treatment was defined as the percentage of patients in each exposure group in treatment on each relative day throughout each of the individual treatment periods starting at the first date of dispensing of the medicine until patient death or last date of data sample. This could be assessed based on the same assumptions and calculations as done for daily dosages.

Co-morbidity and concomitant treatment

Co-morbidities diagnosed before index hospitalization were identified directly using ICD10 codes: myocardial infarction (I21), essential hypertension (I109), atrial fibrillation and flutter (I48), cerebrovascular disease (I6), peripheral arterial disease (I7), chronic kidney disease (N18), malignant condition (C), paroxysmal tachycardia (I47), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (J44), and ischaemic heart disease (I25, I248, I249, I200C). Treatment with a glucose-lowering anti-diabetic medication (ATC code A10), defined as claim of at least one prescription in a period of 90 days before, or up to 60 days after index hospitalization was used as indication to a pre-existing diabetic condition.

Using The Danish Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics we identified patients who had collected a prescription of the following drugs within a period of 90 days before and 60 days after their index hospitalization: loop-diuretics (C03C), thiazide diuretics (C03A), spironolactone (C03DA01), ACE-inhibitors (C09A), statins (C10AA), anti-diabetics (A10) and organic nitrates (C01DA).

Surgical procedures, including coronary interventions (including bypass surgery), pacemaker implantation and heart transplantations, were assessed at baseline and during follow-up via surgical procedure codes.

Outcomes

Two primary endpoints were used: all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization defined as hospitalization for any reason during follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Survival curves were constructed using Kaplan–Meier estimators and compared using log-rank test. Statistical analysis of time to event was performed using Cox proportional hazard models with adjustments for important confounders. Sensitivity analyses were performed testing for homogeneity via subgroup analysis and propensity score matching for time to event. Model assumptions were tested and found valid unless otherwise reported. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Hazard ratios are supplied with 95% confidence interval (CI). The two-sided significance level used is P ≤ 0.05.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (ref 2007-58-0015, internal ref: GEH-2010-001). Retrospective register studies in Denmark do not require ethical approval.

Results

Between 1995 and 2011 212 910 patients were discharged alive after being hospitalized with a first-time diagnosis of heart failure and 58 634 patients aged ≥35 years claimed a prescription of a beta-blocker within 60 days after discharge. A larger fraction of the population was included each year, with 2.31% included in 1995 and 9.28% included in 2010. Men accounted for more than half of each exposure group, most notably in the carvedilol group where 69.5% were men. The most frequently prescribed beta-blocker was metoprolol, accounting for 61.9%, followed by carvedilol (21.1%) and bisoprolol (6.3%). More patients of the bisoprolol group were resident in rural areas at the time of discharge than in the other exposure groups with fewest rural patients in the carvedilol group. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the population.

| Characteristic | Metoprolol | Carvedilol | Bisoprolol | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients n, (% of total) | 36 314 (61.9) | 12 363 (21.1) | 3692 (6.3) | 6265 (10.7) |

| Median age (range) | 75.2 (69.0) | 69.4 (68.1) | 74.5 (63.2) | 74.7 (67.8) |

| Women, n (% of group) | 15 856 (43.7) | 3769 (30.5) | 1602 (43.4) | 3030 (48.4) |

| Median prescription yeara | 2005 | 2006 | 2006 | 2000 |

| Baseline co-morbidity (%) | ||||

| Essential hypertension | 27.5 | 26.7 | 28.4 | 18.7 |

| Myocardial infarction | 23.2 | 21.5 | 21.9 | 12.8 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 27.8 | 29.3 | 31.3 | 20.8 |

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 22.2 | 15.9 | 23.7 | 26.5 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 1.3 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 12.5 | 10.6 | 12.1 | 9.1 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 11.4 | 11.9 | 12.0 | 7.5 |

| Malignant condition | 12.4 | 11.3 | 12.1 | 10.3 |

| Tachyarrhythmia | 6.3 | 5.0 | 7.8 | 8.2 |

| Chronic obstructive | ||||

| Pulmonary disease | 6.6 | 7.8 | 17.2 | 4.1 |

| Concomitant treatment (%)b | ||||

| ACE-inhibitors | 60.1 | 80.3 | 60.4 | 43.5 |

| Loop diuretics | 75.9 | 79.5 | 80.4 | 76.4 |

| Thiazides | 19.2 | 16.2 | 19.6 | 21.0 |

| Spironolactone | 24.3 | 38.5 | 29.6 | 15.3 |

| Statins | 40.6 | 50.8 | 43.1 | 15.2 |

| Antidiabetics | 15.2 | 17.1 | 15.3 | 12.3 |

| Organic nitrates | 30.9 | 23.0 | 31.7 | 27.7 |

| Surgical procedures (%)b | ||||

| Coronary interventions | 14.0 | 16.4 | 12.7 | 5.7 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 4.3 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 2.0 |

| Pre-CHF diagnosis BB treatment | 58.3 | 54.0 | 59.3 | 66.4 |

| Location (% in rural areas) | 71.9 | 69.8 | 85.9 | 75.0 |

- ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; CHF, congestive heart failure; BB, beta-blocker.

- a By these years 50% of the patients in each exposure group had been included due to prescription claim.

- b prescriptions claimed between 90 days before and up to 60 days after discharge date of index hospitalization.

The mean (±SD) follow-up was 4.1 (± 3.5) years. Patients receiving carvedilol were younger, had less co-morbidity but received more concomitant treatment such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitors, spironolactone, and statins. Patients in the ‘other’ exposure group were more likely to have had previous beta-blocker treatment. Regarding coronary surgical procedures, no differences were seen between exposure groups during follow-up. Of the patients receiving carvedilol 8.9% got a pacemaker implant during follow-up against 6.7% metoprolol and 5.6% bisoprolol patients, respectively. No heart transplantations had been performed at baseline while 40 were performed in the metoprolol group, 50 in the carvedilol group and four in the bisoprolol group during follow up.

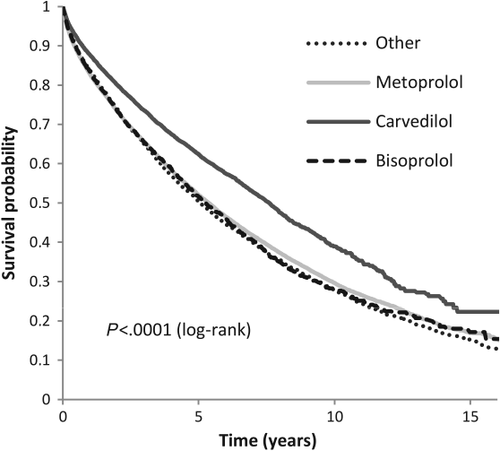

All-cause mortality

In the time of follow-up 30 121 people died from all-causes. Figure 1 shows an unadjusted survival probability plot. An unadjusted Cox proportional hazard ratio (HR) model with metoprolol as reference showed that carvedilol was associated with a significant lower risk of all-cause mortality(HR 0.737, 95% CI 0.714–0.761, P < 0.0001) compared with metoprolol (reference). In contrast, bisoprolol had an insignificantly higher mortality risk (HR 1.020, 95% CI 0.973–1.069, P = 0.4192) and the ‘other’ exposure group had a significantly higher risk (HR 1.044, 95% CI 1.010–1.079, P = 0.0097) compared with metoprolol.

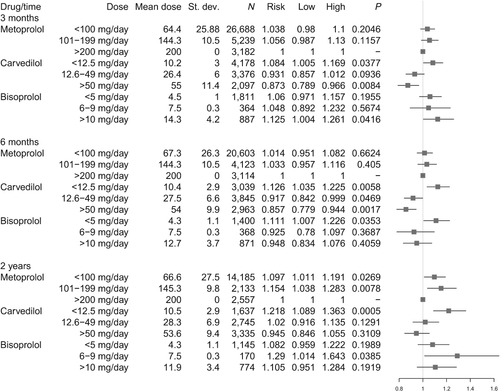

The HRs after adjusting for age, gender, location, prescription period, co-morbidities and concomitant treatment, and following stratification of the exposure groups, is shown in Figure 2. Stratification is based on daily dosages at 3 months, 6 months and 2 years, with high-dose metoprolol as reference in each stratum. Stratification for dosages at 3 months revealed that both intermediate and high daily dose carvedilol was associated with lower mortality, but with the high dose effect being significant (HR 0.873, 95% CI 0.789–0.966, P = 0.0084), compared with high-dose metoprolol. Low-dose carvedilol showed a significantly higher mortality risk compared with high-dose metoprolol. Both low and intermediate dosages of metoprolol showed an insignificant association with higher mortality risk compared with high dose. An insignificant association with higher mortality risk compared with high-dose metoprolol was also seen with low and intermediate dosages of bisoprolol while high-dose bisoprolol showed a significant association with higher mortality (P = 0.0416).

After the same model was applied to exposure groups at 6 months, high daily dose of carvedilol was still associated with the lowest risk of death compared with metoprolol (HR 0.857, 95% CI 0.779–0.944, P = 0.0017), and improved survival for intermediate dose was now seen to be significant (P = 0.0469). Low and intermediate daily dose metoprolol was associated with insignificant higher risk of death, compared with high-dose metoprolol. Insignificant associations with lower mortality were seen with intermediate and high dosages of bisoprolol compared with high-dose metoprolol. With stratification for dosages at 2 years only high-dose carvedilol showed an association with lower but insignificant mortality, (HR 0.945, 95% CI 0.846–1.055, P = 0.3109) compared with high-dose metoprolol.

All-cause hospitalization

A total of 46 990 patients were hospitalized at least once for all-causes in the time of follow-up. Stratification for dosages at 3 months was run with the same Cox model as for all-cause mortality adjusted for the same variables and with high-dose metoprolol as reference. High-dose carvedilol was associated with a significantly lower all-cause hospitalization risk compared with high-dose metoprolol (HR 0.842, 95% CI 0.774–0.915, P < 0.0001) while an insignificantly lower risk was seen with intermediate dosages (HR 0.957, 95% CI 0.890–1.029, P = 0.2382). An insignificant association with lower risk of all-cause hospitalization was seen with low and intermediate dosages of metoprolol (HR 0.965, 95% CI 0.914–1.019; P = 0.1954; HR 0.997, 95% CI 0.935, P = 0.9392), respectively, compared with high dose-metoprolol. Low, intermediate and high dosages of bisoprolol respectively were associated with insignificantly lower all-cause hospitalization risk (HR 0.971, 95% CI 0.892–1.057, P = 0.4981; HR 0.972, 95% CI 0.835–1.132, P = 0.7185 and HR 0.948, 95% CI 0.850–1.057, P = 0.3369, respectively) compared with high dose metoprolol.

Other analyses

During follow-up 9.0% of the patients from the metoprolol group switched to another beta-blocker. The same applied to 9.3% from the carvedilol group, 10.1% from the bisoprolol group, and 17.0% from the ‘other’ group. The pattern of all-cause mortality hazard ratios for dosage groups at 3 months, adjusted for confounders as above, largely did not change compared with the all-cause mortality analysis at 3 months not censored for switch. High- and intermediate-dose carvedilol were still associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality risk (HR 0.864, 95% CI 0.779–0.958, p = 0.057, and HR 0.913, 95% CI 0.839–0.995, p = 0.0381, respectively) compared with high-dose metoprolol. An insignificantly higher mortality compared with high-dose metoprolol was seen with all dosages of bisoprolol.

A propensity score matched analysis with high-dose carvedilol patients as cases (n = 1811) and high-dose metoprolol patients as controls (n = 1811) assessed at 3 months showed a significant lower mortality risk for carvedilol (HR 0.864, 95% CI 0.767–0.973, P = 0.0163). The same analysis with bisoprolol (n = 877) against metoprolol instead showed insignificantly higher mortality risk for high-dose bisoprolol (HR 1.067, 95% CI 0.925–1.232, P = 0.3735). In both analyses exposure groups were matched perfectly for age, gender, location, and all variables of co-morbidity and concomitant treatment as no significant differences were seen between cases and controls. Propensity scores were based on all these variables.

Gender subgroup analyses assessed at 3 months revealed that men receiving high-dose carvedilol had a significantly lower mortality risk (HR 0.846, 95% CI 0.745–0.961, P = 0.0103) compared with high-dose metoprolol. A lower mortality risk for high-dose carvedilol was not significant in the womens' group (HR 0.948, 95% CI 0.800–1.124, P = 0.5403). Women tended to do better on medium doses of carvedilol than the men (HRs 0.879, 95% CI 0.765–1.010, P = 0.0685 and HR 0.963, 95% CI 0.866–1.070, P = 0.4815, respectively). For both genders all other dosage groups had insignificantly higher mortality risks.

In addition, we explored the combined outcome of rehospitalisation owing to major cardiovascular events and death from cardiovascular events, whichever came first: 67.1% patients had an event. The model for dosages at 3 months was applied and no significant difference was found between the high dosage groups with high-dose metoprolol as reference (carvedilol: HR 1.045, 95% CI 0.958–1.140, P = 0.3227; bisoprolol: HR 0.987, 95% CI 0.881–1.105, P = 0.8174).

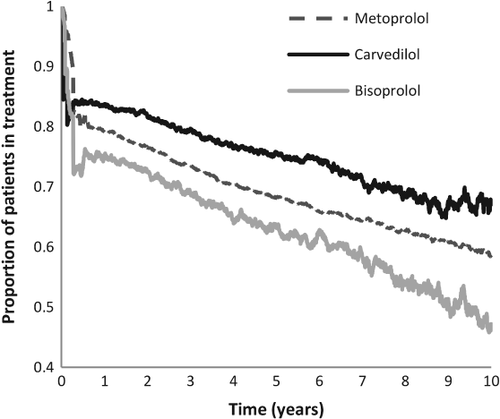

Figure 3 shows the persistence in treatment of the three main exposure groups over time. At 90 days 90.6% of the metoprolol patients were in continuous treatment, with 83.0% for carvedilol and 81.5% for bisoprolol. After 1 year 83.7 % in the carvedilol group were in continuous treatment, with 79.2% in the metoprolol group and 75.3% in the bisoprolol group. This difference between the groups persists throughout the time of follow-up but gradually a lower persistence was seen.

Owing to differences in co-morbidity and concomitant treatment observed, especially in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), between exposure groups at baseline, various interaction analyses were performed but no important interactions were found.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective study performed comparing the clinical outcomes in heart failure patients treated with beta-blockers. We had two main findings: (i) in comparable high doses of carvedilol, metoprolol and bisoprolol, carvedilol was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality risk; and (ii) was also the only dose regimen to significantly lower all-cause hospitalization. The all-cause mortality results persisted when we evaluated dosages at 3 months, 6 months and 2 years after hospital discharge and after we censored for switching type of beta-blocker during follow-up.

The main beta-blockers of our focus (metoprolol, carvedilol and bisoprolol) were chosen on the basis of evidence from randomized trials and guideline recommendations. With metoprolol being the largest group, we chose high-dose metoprolol as the reference for comparison. The first time of estimated dosages at 3 months was chosen to ensure that the patients were receiving their target treatment dose based on the guidelines of up-titrating to the highest tolerated dose over several weeks.

An explanation for our findings could be that patients receiving higher dosages of carvedilol were the ones who best tolerate it because of fewer co-morbidities or lower New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, and thus lower mortality risk. It is worth noting that carvedilol patients received more concomitant treatment for heart failure, such as ACE-inhibitors, than the other groups and therefore could be suspected, on average, to be more morbid than the others and expected to live shorter lives and have more admissions. This interpretation would support our findings but an alternative explanation is that patients who received carvedilol were, in general, treated more intensively despite similar illness and therefore have lower mortality. As we did not include patients diagnosed before 1995 we have a 17 year time-span from 1978 (initiation of registries) onward to check for heart failure diagnosis before their index hospitalization. This makes us confident that the patients included in this study were diagnosed with heart failure for the first time and that our exposure groups therefore are similar in this respect.

It could be speculated that patients in one group were more persistent in taking their medication, which was why we looked into persistence. Figure 3 shows that a high proportion of all three exposure groups were in treatment after several years. It is also seen that carvedilol patients are better in maintaining treatment than the other groups and it cannot be ruled out that this explains a part of the lower risk for mortality and hospitalization found in this group. However, when stratified into dosage groups only the patients who were actually in treatment at that time could be included, in order for them to have a daily dosage to direct them into a stratum. This means that the patients not in treatment at the time do not affect the result in these models. What we could not take into account, as is often the case for a physician, was whether the patients were actually taking their medication.

The insignificant findings with dosages evaluated at 2 years could partly be explained by a decreasing population size and therefore lower power to the model.

Our population size amounts to about one-quarter of all the patients diagnosed with heart failure in the study period. We also saw that out of the patients included in this study, a larger proportion was included in the later years compared with the earlier years. This implies that more patients were being started on beta-blocker treatment or that more people were diagnosed with heart failure in the later years. The first possibility is supported by the fact the earliest randomized controlled trials on the subject were not published until the last part of the 1990s,1, 2, 4 and this could partly explain the three-quarters of the heart failure patients not being put on beta-blocker treatment. To take into account the patient and prescription differences over time we adjusted for the prescription periods in our models.

Any clinical implication of this study should be a consequence of all available data. Several other observational studies that were smaller than ours have shown similar effect15 to that in our study, that metoprolol is superior to carvedilol14 or no significant differences.13, 16, 17 The only randomized study that compared carvedilol with metoprolol used metoprolol tartrate and only gave 50 mg metoprolol daily.7. As the survival benefit with metoprolol1 was documented with a 200 mg dose of metoprolol succinate the head-to-head comparison of metoprolol with carvedilol in COMET has been criticized. Recently a meta-analysis that included all randomized studies of beta blockers20 did not find a significant superiority of carvedilol compared with other beta-blockers. They did report that carvedilol had the numerically largest improvement in mortality and the greatest absolute risk reduction, and based on this suggested carvedilol to the first choice beta-blocker for heart failure. In this context, our study adds to this conclusion. We have no certainty that any beta-blocker is superior to any other beta-blocker at optimal doses. A large randomized study that compares available beta-blockers using the high doses with documented benefit is necessary to answer the question addressed in this study.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is the amount and quality of available data. The diagnosis of heart failure has a high specificity21 and the registration of medication has a high certainty.22

The main limitation is the observational nature of the study. The observed differences may result from confounds not accounted for. We lacked registration of severity of heart failure in terms of NYHA class, blood pressure, and important laboratory data. We acknowledge the importance of these variables as prognostic determining factors whereby the results could be more easily converted into daily clinical practice. The only indicator of severity we had was each patient's concomitant treatment. At the same time we did not look into the formulations of metoprolol dispensed. Another limitation is that our study requires a hospital admission. Patients diagnosed and treated by a general practitioner are not included.

Conclusion

A high dose of carvedilol was associated with a lower mortality risk than high doses of metoprolol or bisoprolol for patients with heart failure when assessed after 3 months and 6 months of treatment. A medium dose of carvedilol was associated with lower mortality risk compared with a high dose of metoprolol only when assessed at 6 months of treatment. Our findings should be viewed in the light of the study design and its strengths and weaknesses.

Acknowledgement

This work was performed at the Institute of Health, Science and Technology, Aalborg University, Denmark

Funding

Conflict of interest: none declared.