ExtraHF survey: the first European survey on implementation of exercise training in heart failure patients

Abstract

Aims

In heart failure (HF), exercise training programmes (ETPs) are a well-recognized intervention to improve symptoms, but are still poorly implemented. The Heart Failure Association promoted a survey to investigate whether and how cardiac centres in Europe are using ETPs in their HF patients.

Methods and results

The co-ordinators of the HF working groups of the countries affiliated to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) distributed and promoted the 12-item web-based questionnaire in the key cardiac centres of their countries. Forty-one country co-ordinators out of the 46 contacted replied to our questionnaire (89%). This accounted for 170 cardiac centres, responsible for 77 214 HF patients. The majority of the participating centres (82%) were general cardiology units and the rest were specialized rehabilitation units or local health centres. Sixty-seven (40%) centres [responsible for 36 385 (48%) patients] did not implement an ETP. This was mainly attributed to the lack of resources (25%), largely due to lack of staff or lack of financial provision. The lack of a national or local pathway for such a programme was the reason in 13% of the cases, and in 12% the perceived lack of evidence on safety or benefit was cited. When implemented, an ETP was proposed to all HF patients in only 55% of the centres, with restriction according to severity or aetiology.

Conclusions

With respect to previous surveys, there is evidence of increased availability of ETPs in HF in Europe, although too many patients are still denied a highly recommended therapy, mainly due to lack of resources or logistics.

Introduction

Exercise training programmes (ETPs) are a key component in cardiac rehabilitation to help patients with cardiovascular disease to recover, and to stay healthy. In heart failure (HF), ETPs are known to reduce the debilitating symptoms, such as breathlessness and fatigue, through effects on the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems. This intervention may reduce recurrences of destabilization, unwanted hospitalization, and ultimately mortality.1

Despite this, ETPs are not widely utilized for HF patients. A European survey showed that <20% of patients with HF are involved in cardiac rehabilitation,2 and, in the UK, ∼900 000 people are living with HF but only a small minority participate in cardiac rehabilitation.3 Several reasons have been proposed, such the costs not being covered, lack of medical and public awareness of their importance, and lack of social/family support.4-6

Awareness of a holistic approach in HF has been advocated in the last HF Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), where it is recommended to encourage regular aerobic exercise training in HF patients in order to improve functional capacity and symptoms, with the highest level of evidence and grade of recommendation.7 However, currently it is not clear how these guidelines are applied in clinical practice and what the possible barriers for their implementation actually might be. The Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC therefore developed the Exercise Training in HF (ExTraHF) Survey to investigate whether and how ETPs are implemented, and to explore the nature of barriers to realize ETPs in order to serve as a basis for possible future policy initiatives. Ancillary aims were (i) the promotion of the awareness of the issue of ETPs in HF in communities of general cardiologists; (ii) to gain insight into the content of ETPs for HF patients in ESC-affiliated countries; and (iii) to promote bench-marking by comparing different centres.

Methods

The study was designed as a web-based survey of cardiac units in countries affiliated to the ESC.

Measures

The ExtraHF Survey questionnaire

- Contact details of the person who filled in the questionnaire.

- The characteristics of the reference hospital/health centres and the size of the treated HF population.

- In the case of absence of an ETP for the HF population, the determining factors.

- In the case of availability of an ETP:

- institutions covering the costs;

- health professional staff involved, and overall responsibility for the ETP;

- the presence of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Phase I: in-hospital programme.

- Phase II: early post-discharge programme. This period is usually 2–16 weeks after discharge where structured and closely monitored exercise, psycho-educational activities, and lifestyle changes are encouraged.

- Phase III: long-term maintenance programme. This is the continuation period of usually less intense supervision.

The modality of exercise training was also investigated (aerobic, resistance, balance, respiratory) and the tests performed to evaluate the efficacy of the ETP. These results will be presented separately.

Study sample and data collection

Identification of and approach to national co-ordinators

The first step was the identification of leaders of national organizations and/or working groups concerned with HF in European countries; they were identified with the collaboration of the HFA Committee on National Heart Failure Societies. For countries without specific national HF organizations, we used a number of approaches including informal contact by committee members of the HFA and/or by writing to the national societies belonging to the ESC. This approach was chosen in order to ensure an optimal response from as many countries as possible.

Initially, we identified 46 national HF co-ordinators, to whom the link to fill in the questionnaire was sent, asking them to forward the surveys to the leading HF centres and the most relevant professionals in their countries. The survey was launched after the May 2013 HFA Scientific meeting in Lisbon, and data were collected until February 2014.

Statistical analysis

We entered the responses of the participating centres into an Excel spread sheet. We undertook frequency analyses for all centres and all patients. The data are presented as absolute numbers and percentages. We also compared the results of implementation of ETPs in the general cardiology units vs. the rehabilitation centres. The comparisons were made using the χ2 test for binary data and Mann–Whitney U-tests for ordinal data. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Table 1 provides an overview of the participating countries. A total of 41 European countries completed the questionnaire. These countries represent 89% of the contacted countries, but 72% of the country members of the ESC.

| ESC-affiliated countries | Centres (n) |

|---|---|

| Armenia | 1 |

| Austria | 2 |

| Belarus | 2 |

| Belgium | 2 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2 |

| Bulgaria | 2 |

| Croatia | 1 |

| Cyprus | 1 |

| Czech Republic | 2 |

| Denmark | 1 |

| Egypt | 3 |

| Estonia | 1 |

| Finland | 4 |

| France | 18 |

| Germany | 6 |

| Greece | 5 |

| Guernsey | 1 |

| Hungary | 3 |

| Ireland | 1 |

| Israel | 2 |

| Italy | 18 |

| Latvia | 1 |

| Lebanon | 1 |

| Lithuania | 2 |

| Macedonia, The Former Yugoslav Republic of | 2 |

| Moldova, Republic of | 1 |

| Morocco | 1 |

| The Netherlands | 3 |

| Norway | 2 |

| Poland | 5 |

| Portugal | 6 |

| Romania | 2 |

| Russian Federation | 4 |

| Slovakia | 1 |

| Slovenia | 4 |

| Spain | 9 |

| Sweden | 1 |

| Switzerland | 3 |

| Turkey | 4 |

| Ukraine | 2 |

| UK | 38 |

The characteristics of the hospital/health centre and the dimension of the treated heart failure population

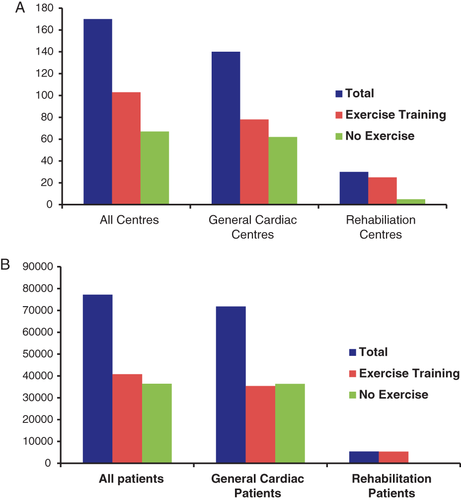

The demographic information provided about participating countries indicates that the survey profile included 170 heart centres, which reported to treat 77 214 HF patients yearly. The majority of these participating centres were general cardiology units (140, 82%), and the remaining 30 (18%) were specialized rehabilitation units. Among the general cardiology units, 53 (38%) were located in a General District Hospital and 87 (62%) in a University Hospital.

The status of the centres was public in 88% (91% for the general cardiology units and 73% for the rehabilitation centres), private in 10%, and not specified in 2%.

Absence of an exercise training programme and reasons

Sixty-seven (39%) of all centres did not implement any form of ETP. These centres accounted for 36 410 (47%) HF patients.

In the case of general cardiology units, 62 centres did not implement an ETP (44%): in terms of the total number of patients, this determined that 36 383 (50.7%) HF individuals did not receive any ETP.

In contrast only 17% of the rehabilitation centres did not include an ETP in their protocol for HF patients, but this accounted for only 0.5% of the HF population followed by these centres (Figure 1)

In 25%, the lack of resources was the reason for not implementing an ETP, mainly due to lack of finances, staff, or equipment. In 19% of the centres, the absence of any form of pathway for an ETP in HF was identified as a main reason for not implementing such a programme: specifically in 10% this was due to a lack of contract with the National Health Service (NHS) and in 9% due to lack of contract with the referring institute. In 13%, this absence was due to a lack of local or national guidelines. In 12% of the respondents, a lack of evidence on safety (6%) or benefit (6%) was perceived.

In almost a quarter of the cases (24%), an ETP was not implemented because this was already provided to the HF patients via different routes: in 13%, patients were admitted to a cardiac rehabilitation programme in the area, while in 11% of the cases, the existing specialist HF services already met the ETP needs of the patient (Table 2).

| % | |

|---|---|

| Not enough resources (times, staff, equipment, accommodation, finances) | 25 |

| ETP is not included in the pathways/contract with the NHS, and/or with the referring institute | 19 |

| ETP in HF is not included in the local guidelines/pathways | 13 |

| Referred to other centres | 13 |

| Lack of evidence of safety or efficacy of ETP in HF | 12 |

| HF services (GPs, OPD) already meet the needs for ETP | 11 |

| Lack of interest from local HF service | 4 |

| Not confident of having the skills mix/knowledge to manage HF patients | 2 |

| Others | 1 |

- ETP, exercise training programme; GO, general practitioner; HF, heart failure; OPD, outpatient department.

Presence of an exercise training programme for heart failure patients: facilitating factors

In 103 (61%) centres, an ETP was implemented, and 40 804 HF patients were treated. In general cardiac units, an ETP was offered in 78 cases (56%), accounting for 35 420 (49%) HF patients. In the case of rehabilitation centres, an ETP was offered in 83% of the cases, accounting for 99.5% of the HF population treated in this setting.

Institutions covering the costs

In 87% of the centres, the NHS covered the costs (83% alone, 4.0% in combination with other institutions), private insurance in 5%, and other forms of financial cover in 8%.

In 87% of the general cardiac centres, the costs of the ETP were covered by the NHS, and private insurance covered only 3.8%. In the rehabilitation setting, the NHS covered 85% of the centres, and private insurance 10%.

Exercise training progremmes currently offered

A wide spectrum of ETPs is currently available in Europe.

Phase I programmes

In 40% of all centres, a phase I in-hospital ETP is offered (typical duration 1–2 weeks, range 1–7 weeks): in 45% of general cardiac centres vs. 24% of the rehabilitation centres (P = NS).

Phase II programmes

The majority of the centres (72%) reported the availability of phase II programmes, but marked differences were seen regarding the types of programmes. In most centres, outpatient (52%) and/or inpatient (25%) programmes existed, while home-based programmes were offered in only 18%.

The typical duration of phase II cardiac rehabilitation programmes also demonstrates a wide spectrum, especially regarding the outpatient programme, ranging from 3 to 52 week duration, on average 11.4 weeks. A programme duration for inpatient programmes of between 2 and 16 weeks (average 2.5) was most often reported. The duration of the home-based ETP was 4.8 weeks (range 0–4).

Phase II programmes were implemented in 76% of the general cardiac centres and in 60% of the rehabilitation centres (P = NS): in the latter group, the home-based programme was present in only one centre.

Phase III programmes

These were implemented in 48% of the centres (range 1–104 weeks duration): this represented 45% of the general cardiac centres (range 1–52 weeks duration) vs. 52% of the rehabilitation centres (P = NS)

Health professional staff involved, and overall responsibility for the exercise training programme

Among the physicians, cardiologists were those most frequently involved (78%), followed by a physician specialized in rehabilitation (64%). Among the nurses, cardiac rehabilitation nurses were the most involved (62%). Among the other healthcare providers, physiotherapists in 64%, dieticians in 59%, psychologists, and exercise physiologists were most commonly part of the team (Table 3)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Cardiologist | 78 |

| Specialist in internal medicine | 15 |

| Specialist in rehabilitation | 64 |

| Physiotherapist | 64 |

| Exercise physiologist | 41 |

| Cardiac rehabilitation nurse | 62 |

| Heart failure specialist nurse | 35 |

| Dietician | 59 |

| Psychologist | 47 |

| Occupational therapist | 19 |

| Others (pharmacists, psychiatrist, respiratory therapist, cardiac surgeon, neurologist) | 11 |

In the general cardiac centres vs. the rehabilitation centres there were higher representations of cardiologists, specialists in rehabilitation, physiotherapists, HF specialist nurses, dieticians, and occupational therapists.

The cardiologist had overall responsibility for the ETP in 64 of the centres (in 72% alone, in 29% in collaboration with other healthcare providers), and the nurse had overall responsibility in 22% of the centres (cardiac rehabilitation nurse in 18%, HF nurse in 4%). In the rehabilitation centres, the responsibility of cardiologists was similar to that in the general cardiac units (60% vs. 62%, P = NS), but the role of the HF nurse was not significantly higher (20%, vs. 17%, P = NS).

Inclusion criteria

The ETP was offered to all HF patients (independently of the severity, aetiology, or patient characteristics) in 57 (55%) centres. In 39 centres (38%), it was offered only to HF patients who were referred because of a recent acute myocardial infarction or revascularization, and in 36 (35%) only to HF patients with specific conditions such as cardiomyopathy, valve disease, or hypertension. In 9 (9%) centres, HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF) was not considered an inclusion criterion.

No significant difference between the general cardiac centres and the rehabilitation centres was detected, with the exception of HFPEF which was considered an exclusion criterion in nine general cardiac centres only.

Exclusion criteria

In 61 centres out of the 68 which do not offer an ETP (90%), a particular NYHA class was considered an exclusion criterion (multiple answers were accepted): NYHA class IV patients were excluded in >40% of the centres; this applied to both the general cardiac and the rehabilitation centres (Figure 2).

In nine centres (13%), particular LVEF values were considered exclusion criteria: <35% in six centres. In four centres (6%), particular peak oxygen consumption values were considered exclusion criteria: <12 mL/kg min in two. These exclusion criteria applied to the general cardiac centres only.

Discussion

This survey provides a comprehensive overview of the current status of ETPs in Europe. In fact it collects experiences from 89% of the contacted European countries, that completed the questionnaire (representing 72% of the country members of the ESC).

The first observation from the findings presented here is a positive and encouraging one: in contrast to a previous survey,2 60% of the cardiac centres in ESC-related countries have developed a programme of exercise training for their HF patients. Bethell et al. revealed that in the UK less than one-third of patients after acute coronary syndrome undergo an ETP based on the Heart Manual.3 In contrast, our survey shows the increased awareness of the importance of a secondary prevention intervention in the HF population, where exercise training plays a major role.1

However, our data also carry some lights and shadows.

The data highlight the very different level of development and coverage of exercise training in HF services across different centres, which is in keeping with the well-known disparities existing among European countries: while some have detailed national guidelines, funding mechanisms, and provision of services to patients, others have few frameworks and limited service availability.2

Almost 40% of the surveyed cardiac centres in Europe did not implement ETPs for patients with HF, and, furthermore, half of the HF population admitted to general cardiac centres are not prescribed any ETP. This is in contrast to the general consensus from most of those completing the survey who accepted that there was good scientific evidence of benefit. This is not a new concern and it is in keeping with the most recent literature.2, 4, 5

There were several reasons for not implementing an ETP in daily practice in a lot of countries. Most of the responders, HF specialists, regarded the major barriers to providing a service for HF as lack of resources, mainly due to lack of finances, staff, and equipment. As a partial compensation for this, there is evidence that in almost a quarter of the cases, local commissioning arrangements, local patient pathways, or other people (e.g. HF specialist nurses) were providing a similar service. Accordingly, these HF patients do exercise, even though in different settings. Finally, only a very small number expressed doubt about safety, or their competency.

The fact that 12% of our colleagues still feel that there is a lack of evidence of benefit shows that there is a need for constant activities on education and training.

Also among the centres that had an ETP for HF patients, there was an important limitation in its implementation. In fact in only 55.3% of the centres it was proposed to all HF patients, with restrictions according to severity or aetiology. For example, patients with less severe forms of systolic heart failure (NYHA class II and III) after a heart attack or coronary revascularization have the best chance of being offered an ETP. Although there is preliminary evidence of more beneficial effects in more severe and advanced conditions of HF,8 NYHA class IV patients were excluded in >40% of the centres.

Limitations of the study

Table 1 highlights the non-uniform participation of all European cardiac centres, with differences from country to country, which may have affected the findings. In particular, there is an imbalance in the distribution of the participants among different countries, questioning how representative the results are for Europe. On average, barely more than four centres per country contributed by replying to this survey. Thus it is plausible that the centres with a special interest in HF were more involved, thus affecting the validity of extrapolating the results found to the overall population. To reduce this risk, we specifically addressed this web-based questionnaire to the leaders of HF national organizations and/or working groups in European countries, asking them to forward the surveys to the leading HF centres and the most relevant professionals in their countries. This approach was chosen in order to try to obtain the best and the most complete possible answers.

Also the predominance of general cardiology centres vs. rehabilitation centres has affected any proper comparisons in the resources and ETPs offered.

The survey was designed to be simple and easy to fill in, with little crucial information requested. However, the questionnaire was still quite detailed and it is impossible to know how many of the centres involved have reliable data available to answer these questions. In larger institutions in particular, many different physicians refer HF patients to exercise-based rehabilitation and unless a centre prospectively registers data on all HF patients including ETPs, it might have been challenging to provide adequate data to respond to the survey. In order to reduce the risk of the poor reliability of the information submitted, we tried to limit the complexity of the requested items. Still the absolute quality of the data could not be assured.

Recommendations from this study

In 20% of the centres, non-implementation of an ETP was due to scientific underestimation or inadequate dissemination of the utility and safety of ETPs which might lead to lack of interest or conviction. Accordingly, a quarter of the centres might be potentially active if effectively instructed and supported. Although at first glance these are negative findings, they do represent a stimulus for further dissemination of ETP cultures and procedures. There is much expertise available from colleagues within and across European countries to support expansion of ETP services to a greater number of European citizens. The HFA and other ESC associations (namely the EACPR) have an important cross-fertilizing role in sharing expertise and in supporting colleagues to develop better services at important milestones in effort in their own countries. Alongside the scientific exchange and development that the HFA currently enables, it is timely that the Associations share knowledge and experiences and to drive development of legislative, funding, and structural aspects of ETP service provision in HF. It is only by working together that ETPs can be positioned as a mainstream service championed and supported by all cardiologists and funded as a priority for health systems across a Europe faced with an increasing burden of cardiovascular disease in the coming generations.

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to Viviane Conraads who passed away at the age of 50, during the process of finalizing this project. Viviane was a bright scientist, a warm-hearted person, and a great inspiration to many. She is greatly missed by all who had the privilege to know her.

European Heart House staff (Aurelia Bregeras, Anya Craser, and Francois Durand) are thanked for their indispensable support for the development of the web questionnaire. We are grateful to Aldo Maggioni for his essential contribution to the revision of the questionnaires. We also thank the European Association for Cardiovascular Rehabilitation and Prevention of the ESC for the endorsement, and the National Co-ordinators and those responsible for the heart failure centres in European countries (see below).

Participating countries and contributors

Armenia: Aram Chilingaryan, Lusine Tunyan, Shogik Martirosyan, Anna Stepanyan. Austria: Friedrich Fruhwald, Christian Ebner. Belarus: Eugene Atroschenko, Natallia Maroz-Vadalazhskaya. Belgium: Poncelet Alain, Martine Antoine. Bosnia and Herzegovina: Fahir Barakovic. Bulgaria: Malina Antova, Plamen Gatzov. Croatia: Davor Milicic. Cyprus: Vassilis Barberis. Czech Republic: Filip Málek, Jaromir Hradec. Denmark: Finn Gustafsson. Egypt: Magdy Abdel Hamid, Mahmoud Hassanein, Yahia Elrakshy. Estonia: Tiina Uuetoa. Finland: Mathias Hoglund, Matti Kotila, Jari Laukkanen, Heikki Miettinen. France: Guillaume Jondeau, Frederic Mouquet, M F Seronde, Jean-Noel Trochu, Nadia Aissaoui, Alan Cohen Solal, Patrick Jourdain, Marie Christine Iliou, Patrick Aeberhard, Bernard Truong Minh Ky, Anne Ponchon, Barnabas Gellen, Jean Marie Casillas, Francois Picard, Pavy Bruno, Catherine Monpere, M. Salvat. Germany: Till Neumann, Ralf Westenfeld, Stephan von Haehling, Heinz Völler, Martin Halle, Birna Bjarnason-Wehrens. Greece: Apostolos Karavidas, Christina Chrysohoou, Ioannis Terrovitis, Evangelia Kouidi. Guernsey: Sophie O'Connell. Hungary: Eva Simon, Attila Simon, Judit Bakai. Ireland: Denise Duggan. Israel: Alicia Vazan Fuhrmann, Tuvia Ben Gal. Italy: Mariachiara Calabrese, Attilio Iacovoni, Massimo Maccherini, Massimo Mancone, Michele Correale, Letizia Reggianini, Copelli Silvia, Serena Bergerone, Antonio Loforte, Simone Binno, Pietro Palermo, Francesco Formica, Andrea Montalto, Vincenzo Tarzia, Anna Frisinghelli, Fabio Bellotto, Giuseppe di Tano, Gabriella Malfatto. Latvia: Gita Rancane. Lebanon: Hadi Skouri. Lithuania: Ausra Kavoliuniene, Jelena Celutkiene. Macedonia, The Former Yugoslav Republic of: Elizabeta Srbinovska Kostovska, Sheshoski Bojan. Moldova: Eleonora Vataman. Morocco: Najat Mouine. The Netherlands: Nicole Uszko-Lencer, K. Caliskan, J. Brügemann. Norway: Lars Gullestad, Tone Figenschau Seppola. Poland: Jaroslaw Drozdz, Alicja Dabrowska-Kugacka, Zdzislaw Juszczyk, Mariola Szuli, Kinga Wgrzynowska-Teodorczyk. Portugal: Ana Abreu, Antonio Arsenio, Brenda Moura, Luís Pedro Alves Tavares, Filipa Almeida, Paulo Bettencourt. Romania: Dragos Vinereanu, Christodorescu Ruxandra. Russian Federation: Elena Yury Lopatin, Maria Glezer, Peter Fedotov. Slovakia: Alexander Klabnik. Slovenia: Mitja Lainscak, Janez Poklukar, Mitja Letonja, Katarina Sladekova. Spain: Juan F. Delgado, Francisco Epelde, Ines Gomez, Manuel José Fernández Anguita, Carla Fernandez Vivancos, José González Costello, Javier Segovia, Regina Dalmau, Josep Lupón. Sweden: Maria Schaufelberger. Switzerland: Jean-Paul Schmid, Eric Gobin, Frank Enseleit. Turkey: Yuksel Cavusoglu, Mustafa Gokce, Ibrahim Sari, Sinem Aras. Ukraine: Leonid Voronkov, Olga Barnett. UK: Mark Petrie, Hazel Phillips, Rebecca Chawner, Claire Arditto, Hannah Manos, Clare Hardman, Deirdre Milnes, Rachel Owen, Joanna McGrady, Gillian Fitnum, Catherine Mcilduff, Diane Kidman, Sarah Vickers, Liz Britton, Linda Llewellyn, Frieda Rimmer, Patricia Marson, Kathryn Carver, Karen Collins, Wendy Veevers, Tamara Hurst, Linda Barratt, Bernie Downey, Michael Alvey, Jane Brooks, Paula Emery, Fiona Sawyer, Celia Bloor, Theresa Rowley, Sharon Faulkner, Alison Hylton, Katherine Moore, Pippa Sansom, Nicki Simpson, Laura McGarrigle, Sharon Hyde, Joanne Gilchrest, Patrick Doherty.

Funding

An unrestricted grant from the Heart Failure Association.