The evidence for pharmacist care in outpatients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Abstract

Aims

Patients with heart failure (HF) have poor outcomes, including poor quality of life, and high morbidity and mortality. In addition, they have a high medication burden due to the multiple drug therapies now recommended by guidelines. Previous reviews, including studies in hospital settings, provided evidence that pharmacist care improves outcomes in patients with HF. Because most HF is managed outside of hospitals, we aimed to synthesize the evidence for pharmacist care in outpatients with HF.

Methods and results

We conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and integrated the evidence on patient outcomes in a meta-analysis. We found 24 RCTs performed in 10 countries, including 8029 patients. The data revealed consistent improvements in medication adherence (independent of the measuring instrument) and knowledge, physical function, and disease and medication management. Sixteen RCTs were included in meta-analyses. Differences in all-cause mortality (odds ratio (OR) = 0.97 [95% CI, 0.84–1.12], Q-statistic, P = 0.49, I2 = 0%), all-cause hospitalizations (OR = 0.86 [0.73–1.03], Q-statistic, P = 0.01, I2 = 45.5%), and HF hospitalizations (OR = 0.89 [0.77–1.02], Q-statistic, P = 0.11, I2 = 0%) were not statistically significant. We also observed an improvement in the standardized mean difference for generic quality of life of 0.75 ([0.49–1.01], P < 0.01), with no indication of heterogeneity (Q-statistic, P = 0.64; I2 = 0%).

Conclusions

Results indicate that pharmacist care improves medication adherence and knowledge, symptom control, and some measures of quality of life in outpatients with HF. Given the increasing complexity of guideline-directed medical therapy, pharmacists' unique focus on medication management, titration, adherence, and patient teaching should be considered part of the management strategy for these vulnerable patients.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a prevalent, highly morbid, chronic progressive, and costly condition with a growing impact on public health, affecting approximately 1–2% of the adult population in developed countries.1, 2 Guideline-directed drug therapy in patients with HF is increasingly complex. It reduces HF-related hospitalizations as well as mortality and can increase the quality of life (QoL) and physical performance,3 however, brings a high burden of drug therapy to patients, including inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system, beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, neprilysin inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, ivabradine, diuretics, digoxin/digitoxin, vericiguat, hydralazine/nitrates, and so forth.

The complexity, multimorbidity and heterogeneity of the syndrome increases the probability of medication non-adherence, patient confusion, and severe adverse effects. Drug/drug interactions, contraindications, duplicate medications, adverse effects and, in particular, medication non-adherence are major causes of HF exacerbation,4 whereas improving medication adherence has shown to result in lower frequencies of hospital admissions and decreased mortality.5, 6

For many outpatients, it is difficult to self-manage their many pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments.7 Hence, multidisciplinary approaches to support HF patients in their everyday management are promising to improve outcomes with pharmacists contributing as part of an interdisciplinary team.8-10 Pharmacists in community practice are highly accessible providers in the healthcare system. Patients only see their cardiologist periodically; however, they see their pharmacists many times between physician visits. As professionals with expertise in drug therapy, regular patient encounters and direct communication with general practitioners, pharmacists hold great potential for successful HF outpatient care.

Some systematic reviews have been performed to analyse the impact of pharmacist care on HF patients.11-13 Koshman et al. included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) until August 2007 that evaluated the impact of pharmacist care on patients with HF in both inpatient and outpatient settings.12 Kang et al. included both RCTs and prospective observational studies including patients diagnosed with HF, left ventricular dysfunction (LVD), coronary artery disease (CAD) and acute coronary syndrome (ACS).11 Finally, Parajuli et al. evaluated the role of pharmacist-involved multidisciplinary HF management in English-language RCTs performed in all kind of settings through March 2017.13 However, given the importance of outpatient care for HF, we aimed to synthesize the available evidence for pharmacist care in outpatients with HF.

Methods

A systematic literature search of RCTs of pharmacist care in HF outpatients was conducted in PubMed from its inception to December 16, 2019. If justified, the evidence was integrated in a meta-analysis. The following search strategy was applied: ((‘heart failure’[Text Word]) AND (pharmacist*[Text Word] OR pharmacy[Text Word] OR pharmacies[Text Word] OR ‘pharmaceutical care’[Text Word] OR ‘community pharmacy’[Text Word] OR ‘community pharmacies’[Text Word])) AND (management[Text Word] OR intervention*[Text Word] OR prevention[Text Word] OR service*[Text Word] OR ‘medication review’[Text Word] OR detection[Text Word] OR identification[Text Word] OR progression[Text Word] OR symptom control[Text Word] OR ‘drug related problem’[Text Word] OR polymedication[Text Word] OR lifestyle[Text Word] OR prognosis[Text Word] OR ‘patient compliance’[Text Word] OR ‘medication adherence’[Text Word] OR ‘drug adherence’[Text Word])We also scanned reviews for further publications that were not found with the above-named search strategy. We scanned titles and then assessed for relevant abstracts and full-text articles.

We predefined the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: We considered articles in English, German, French, Dutch, and Spanish. We included RCTs considering HF patients that received pharmacist care to manage their disease in the outpatient setting, also considering pharmacist led-transition of care programs from the hospital with that aim. We excluded RCTs that investigated pharmacists' care during hospital stay of HF patients as well as papers that were duplicates, descriptions of study protocols (without providing results), and those that did not report specific pharmacist interventions.

We repeated the search strategy on 9 February 2021.

Meta-analyses

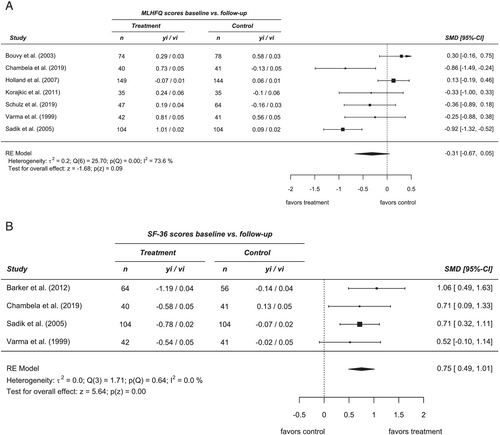

All statistical analyses were carried out using the metafor package14 in R statistics 3.6.115 following the guidelines of Borenstein et al.16 The influence of pharmacist care on clinical outcomes of HF outpatients (all-cause and HF hospitalizations and deaths) was assessed by computing the odds ratio (OR) as well as the standard error (SE) in each study based on the frequencies of corresponding patients in the intervention and control group. The influence of pharmacist care on QoL was assessed by computing the standardized mean difference (SMD) and SE for the changes in the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ, a HF-specific QoL instrument) and of the short-form 36 (SF-36, a generic QoL instrument) test scores between the intervention and control group for each study. Following the usual cut-off criteria SMDs in the order of at least 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were regarded as small, medium and large, respectively. For studies reporting results for more than one test score (MLHFQ and SF-36 or different scales of the SF-36) the mean SMD and SE across the different scores was computed.

Forest plots were generated to provide an overview of the study results. The meta-analytic integration was carried out based on a random-effects model as studies differed with respect to sample (e.g. age and sex distribution) and study characteristics (e.g. duration of the follow-up periods). ORs were log-transformed before performing the MA and the results were converted back into the original metric.

We computed the overall ORs (for the clinical outcomes) or SMDs (for the changes in QoL) corrected for sampling error, the population variances, the 95% confidence intervals. The Q- and I2-statistic were used to assess heterogeneity. A significant Q-statistic as well an I2-statistic above 75% were considered to indicate heterogeneity. If outcomes were measured on multiple occasions, for example, QoL, we used the data for the latest point in time. Data that could not be extracted from the publications was asked to be provided from the authors.

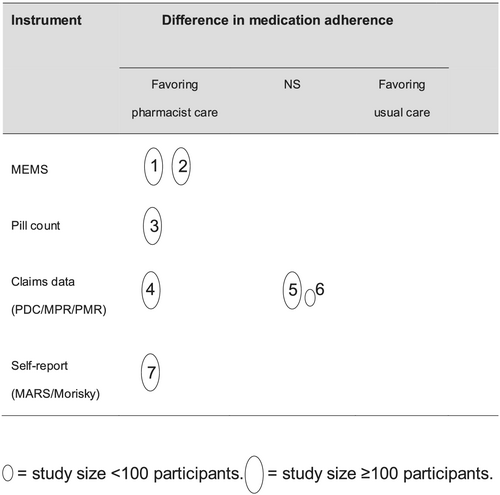

Adherence

Data on the primary outcome medication adherence was collected in a Harvest plot,17 illustrating the effect of pharmacist care. Studies are presented in ovals weighted by the sample size and sorted by their effect as well as the measuring instrument: Medication Event Monitoring Systems (MEMS), pill count or filled prescriptions, claims data,18 and self-reports.19, 20

Results

Literature search

The search (16 December 2019) resulted in 496 articles, with 61 titles of interest including 22 RCTs and 39 reviews (Figure 1). The reviews were scanned for additional RCTs, identifying one additional RCT.9

A repetition of the search on 9 February 2021 resulted in one additional RCT fulfilling the inclusion criteria.21 The total of 24 RCTs, summarized in Supporting Information, Table S1, were performed in 10 different countries, including 8029 patients. Study duration ranged from 30 days up to 4.7 years.

Pharmacist interventions

We found a variety of pharmacist interventions to support HF patients in the outpatient setting (Supporting Information, Table S1). These mainly involved medication management (defined as continuous multidisciplinary care following a medication review to optimize drug therapy and to decrease patient risks), assessing symptom control, and providing patient education. Pharmacists performed the intervention in community pharmacies or study pharmacies,8, 22-25 in outpatient clinics,9, 26-31 in patient homes,32-38 at telephone appointments21, 34, 38 or appointments in hospitals at/post discharge.39-41 Most interventions included repeated consultations.8, 9, 21, 24-26, 28, 32, 33, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41

Pharmacist-conducted medication reviews were evaluated in 12 RCTs.22, 25, 27-32, 34, 35, 38 Within the context of continuous care, pharmacists developed or updated medication plans22, 25, 28, 33, 41 and monitored HF medications with respect to guideline concordance or the medication appropriateness index (MAI).23, 27, 28 They supported regular medication supply, for example, by filling dosing aids,22, 25, 36, 42 and coordinated discharge medication within transitions of care.22, 36 They also ensured that patients kept a follow-up appointment with their physician after hospital discharge.21, 32 Pharmacists assessed symptom control (e.g. checking for changes in weight or blood pressure)21, 22, 24, 25 and monitored laboratory results.21, 37 They performed patient education on a variety of topics.9, 22, 24, 26, 27, 30-33, 35-42

The majority of identified pharmacist interventions led to improvement of knowledge (as measured by questionnaires concerning general knowledge and treatment of HF),9, 30, 31, 33, 39 physical function (reported as improvements in corresponding domains in QoL instruments, forced vital capacity, or 2-min and 6-min walking distance, respectively),30, 31, 33 disease and medication therapy management (measured, e.g. by appropriate furosemide dose adjustments or chronic disease management quality of care scores),9, 34 and concordance with guidelines.34, 41

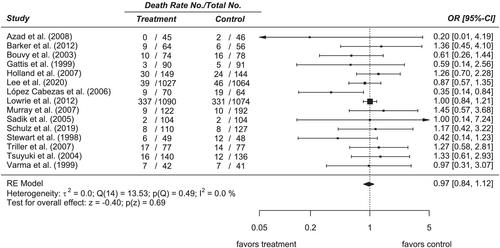

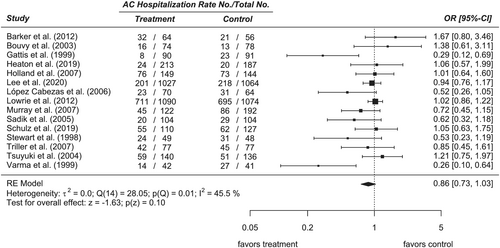

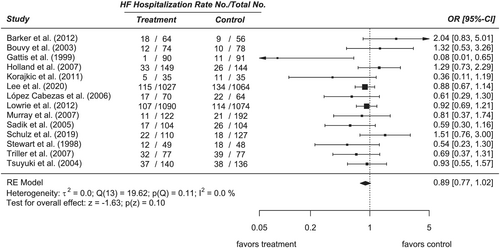

The overall influence of pharmacist care on all-cause mortality, all-cause and HF hospitalizations are presented in Figures 2-4. The mean odds ratio (OR) for all-cause mortality was 0.97 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.84–1.12], P = 0.69. An insignificant Q-statistic and an I2-value of 0% indicated no heterogeneity (Figure 2). The mean OR for pharmacist care compared with control showed a non-significant reduction in all-cause hospitalizations (OR = 0.86 [95% CI, 0.73–1.03], P = 0.10, Figure 3) and HF hospitalizations (OR = 0.89 [95% CI, 0.77–1.02], P = 0.10, Figure 4). There was medium heterogeneity in the results for all-cause hospitalizations (Q-statistic, P = 0.01, I2 = 45.5%) but not for HF hospitalizations (P = 0.11; I2 = 0%).

Considering the MLHFQ scores, we found a small mean SMD of −0.31 [95% CI, −0.67 – 0.05], P = 0.09. Both the Q-statistic (P < 0.01) and I2-statistic (73.6%) indicated heterogeneity (Figure 5). The SF-36 results yielded a medium SMD of 0.75 ([95% CI, 0.49–1.01], P < 0.01), with no indication of heterogeneity (Q-statistic, P = 0.64; I2 = 0%) (Figure 5).

Adherence

The Harvest plot illustrating the effect of pharmacist care on the primary outcome medication adherence in seven studies in relation to the different measuring instruments is shown in Figure 6. Two studies used MEMS,8, 24 one used pill count,33 three analysed claims data,25, 31, 41 and one used self-reports.30 The identified overall impact strongly favoured pharmacist care in five trials utilizing different methods to measure medication adherence.

Discussion

Modern guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure (HF) is complex, but improves patient outcomes. Given the complexity and burden of medical therapy for HF, we explored the role of pharmacists in the outpatient care of these patients. In our systematic review, we found that pharmacist interventions in outpatients improved a variety of surrogate, although important outcomes, such as medication adherence, knowledge, physical function, disease and medication therapy management, concordance with guidelines and improvements in quality of life. Pharmacist care of outpatients with HF did not consistently translate into improvements of readmission rates or mortality. Patients need evidence-based solutions to the many challenges they face with regards to medical therapy of HF. The totality of the evidence suggests that pharmacists should be part of the outpatient care of patients with HF.

Our review concurs with previous work on pharmacist interventions regarding HF patients. Parajuli et al. updated the findings of Koshman et al. on interdisciplinary HF management including pharmacists.12, 13 Both systematic reviews stated a significant reduction of all-cause and HF hospitalizations but no improvements regarding mortality. As they did not focus on pharmacist care for outpatients, they included different evidence from ours. For our RCT selection, the point estimates of all-cause and HF hospitalizations and mortality suggested benefits, but were not statistically significant. Kang et al. combined studies on patients with different diagnoses (HF, LVD, CAD, and ACS) and reported no significant improvements in HF hospitalizations and mortality.11 Especially for these clinical outcomes, we agree with Parajuli et al. pointing out the insufficient time of follow-up as well as the lack of power to measure a considerable impact in the RCTs available.13

Our review adds a systematic approach to evaluate the results of pharmacist care on medication adherence. Non-adherence to HF medication is a major cause for hospital (re-)admissions, and relates to higher costs and mortality.4, 43-45 It has been shown, first, that it is difficult to improve medication adherence meaningful46 and, second, that poor medication adherence cannot be persistently “cured”; it decreases after stopping the interventions to improve adherence,24 indicating a need for a continuous strategy. Frequent and continuous visits to the community pharmacist as healthcare provider are a promising approach.25

Despite proven benefits and strong guideline recommendations, medication usage and dosing remain suboptimal in routine clinical practice.3, 45, 47, 48 Including pharmacists in a multidisciplinary care team improves guideline-directed use of HF medications.23, 49-51 As member of the team, they add especially to the optimization of HF drug therapy with their deep knowledge of safe and efficient medication therapy by providing medication reviews, avoiding drug interactions, and supporting adherence.25, 28 Cooperation between pharmacists and HF nurses would provide comprehensive patient education and combine their often complementary skills.36, 39 For both occupational groups there is evidence that their interventions in HF patients improve clinical outcomes,12, 13, 52, 53 thus complementary effects could be expected.

The studies reviewed report a variety of pharmacist interventions. Based upon our systematic review, we recommend the following for pharmacist care for outpatients with HF: medication reviews (including a medication plan),54 adherence support, supporting symptom control, and providing education on HF management (Table 1).

| Intervention | Components of care |

|---|---|

| Medication review (Medicine Use Review)22, 25, 28, 30-32, 34 |

- Check of current medication using prescription/dispensing data and/or brown-bag interview22, 25, 28, 30-32 • Use as prescribed? • According to evidence-based guidelines? • Potential for optimization: DRP such as double medication or drug/drug- or drug/food-interactions, unreached target doses, complex or inconvenient dosing schemes, expired medication? • Self-medication (use of OTC drugs)? - Patient interview on current medication use25 - Discussing identified DRP and possible optimizations with treating physician(s)/multidisciplinary team25, 28, 30, 31, 34 |

| Adherence support8, 22, 24, 25, 28, 36, 42 |

- Discussing reasons for non-adherence with patients8 - Reinforcing medication adherence by explaining the importance for therapy success8, 28, 42 - Providing/preparing dosing aids22, 25, 36, 42 or specially labelled medication24 •Explaining use of dosing aids considering the current drug regimen42 - Providing, updating, and explaining the current medication plan22, 25, 28 or explaining the current drug regimen24 |

| Supporting symptom control22, 24, 25 |

- Measuring blood pressure and pulse at pharmacy visits25 - Providing logs for self-monitoring of weight, blood pressure and further vital signs22 - Monitoring of bodyweight records via database24 |

| Patient education on HF management9, 22, 24, 30-33, 36, 39, 40, 42 |

- Medication management9, 24, 32, 36 • Incorporating intake in daily routines • Self-adjusting diuretic dosing - HF disease9, 22, 30, 31, 39, 40, 42 • Supporting knowledge and understanding of HF syndrome ▪ Symptoms, signs and causes for impairment • Supporting self-monitoring ▪ Identifying symptoms/signs of fluid retention (oedema) ▪ Instructions on handling identified symptoms (immediate contact to treating physician, medicinal measures) - (HF) medication9, 22, 24, 30, 31, 33, 36, 39, 40 • Verbal explanation/written information leaflets on (newly) prescribed drugs ▪ Effects and side effects |

- DRP, drug-related problem; HF, heart failure; OTC, over-the-counter (non-prescription medicines).

Limitations

Our review has some limitations that warrant discussion. We searched only one database - although the most relevant - for publications which might limit the extent of our findings. However, we used systematic reviews to identify further publications we might have missed. By this, we added only one further publication thereby supporting the comprehensiveness of our findings. With respect to clinical outcomes, we suspect the majority of studies had insufficient power, as the clinical outcomes were not always the primary objective and had short periods of follow-up to detect significant differences, which may explain some of the heterogeneity of the results.

We acknowledge that the available evidence did not show a significant impact on HF outpatients' mortality and hospitalizations, although previous reviews showed a significant effect on hospitalizations.12, 13 These differences can be explained by the exclusion of RCTs of pharmacist interventions on hospitalized HF patients in our review and meta-analysis. Rates of re-hospitalization are much higher in patients who have already been hospitalized. So similar relative risk reductions in HF outpatients will reach statistical significance with only a much higher number of included patients in these studies.

Another limitation was the broad variation and combinations of pharmacists' interventions that hampered the identification of their particular effects. Because we assumed that pharmaceutical care is always a conglomerate of different interventions, we interpreted these synergistic actions in the favour of real-life circumstances. However, there is still research needed to compare identical, well-defined intervention programs and their effects.

Conclusions

Pharmacist care improves medication management, adherence and knowledge, symptom control and possibly quality of life in outpatients with HF. Given the increasing complexity of guideline-directed medical therapy, pharmacists' unique focus on medication management, titration, adherence, and patient teaching, should be considered part of the management strategy for these vulnerable patients.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following authors of primary studies who answered our requests for further information: John McMurray, Pamela Heaton, William Hogg, Carmel Hughes, Adel Sadik, James McElnay, Frank Molnar, and Susan Poole. We also thank Katrin Krueger for her thorough preliminary work in the literature search and an early draft of the manuscript. Finally, thanks to Margit Schmidt, Department of Medicine, ABDA, Berlin, for her support in searching and retrieving the literature.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Funding

None received.