Association of anaemia and all-cause mortality in patients with ischaemic heart failure varies by renal function status

Abstract

Aims

The aims of the current study were to evaluate the association between anaemia and all-cause mortality according to chronic kidney disease (CKD) status and to explore at what level of haemoglobin concentration would the all-cause mortality risk increase prominently among CKD and non-CKD patients, respectively.

Methods and results

This is a prospective cohort study, and 1559 patients with ischaemic heart failure (IHF) were included (mean age of 63.5 ± 11.0 years, 85.8% men) from December 2015 to June 2019. Patients were divided into the CKD (n = 481) and non-CKD (n = 1078) groups based on the estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. In the CKD group, the incidence rate of all-cause mortality in anaemic and non-anaemic patients was 15.4 per 100 person-years and 10.8 per 100 person-years, respectively, with an incidence rate ratio of 1.42 (95% confidence interval: 1.00–2.02; P-value = 0.05). In the non-CKD group, the incidence rate of all-cause mortality in anaemic and non-anaemic patients was 9.8 per 100 person-years and 5.5 per 100 person-years, respectively, with an incidence rate ratio of 1.78 (95% confidence interval: 1.20–2.59; P-value = 0.005). After a median follow-up of 2.1 years, the cumulative incidence rate of all-cause mortality in anaemic and non-anaemic patients was 41.5% and 44.1% (P-value = 0.05) in the CKD group, and 30.9% and 18.1% (P-value < 0.0001) in the non-CKD group. In the CKD group, cumulative incidence rate of all-cause mortality increased prominently when haemoglobin concentration was below 100 g/L, which was not observed in the non-CKD group.

Conclusions

Results of the current study indicated that among IHF patients, the association between anaemia and all-cause mortality differed by the renal function status. These findings underline the importance to assess mortality risk and manage anaemia among IHF patients according to the renal function status.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is common among patients with heart failure (HF), with a reported prevalence of approximately 30–50%.1-5 Compared with HF patients without CKD, those with CKD have a higher mortality risk.3, 6-9 The theories to explain these observations include greater co-morbid burdens, accelerated atherosclerosis, less use of guideline-recommended therapies, CKD-associated mechanisms, and among others.10-12

Anaemia is a well-known complication of CKD due to the inability of synthesizing sufficient erythropoietin in the renal peritubular cells.13, 14 In addition, chronic inflammation associated with CKD impairs iron absorption, transport, and turnover, resulting in decreased iron utilization and haemoglobin synthesis.13, 14 Studies have demonstrated that anaemia associated with CKD was an independent risk factor for in-hospital and 1 year mortality among patients with HF.15-17 Nonetheless, whether the association between anaemia and mortality varied by CKD status is unclear. In addition, at what level of haemoglobin concentration would the mortality risk increase prominently in CKD and non-CKD patients is undetermined. These two issues have important implications on mortality risk assessment and clinical management among HF patients with coexistent CKD and/or anaemia.

Accordingly, the aims of the current prospective ischaemic heart failure (IHF) cohort study were to evaluate the association between anaemia and all-cause mortality among CKD and non-CKD patients, respectively, and then to explore at what level of haemoglobin concentration would the all-cause mortality risk increase prominently among CKD and non-CKD patients, respectively.

Methods

Study participants

This is a single-centre, prospective cohort study. The current study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital (No. 2017128H), and written informed consent was obtained before enrolment. From December 2015 to June 2019, patients who were hospitalized in the Department of Cardiology, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital were consecutively screened for the eligibility of the current study by study investigators. The included criteria were as follows: (i) ≥18 years of age; (ii) ischaemic heart disease as confirmed by coronary angiography, prior myocardial infarction, and/or prior revascularization; (iii) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 45% as assessed using echocardiogram during index hospitalization; and (iv) symptomatic or asymptomatic HF. HF patients with LVEF < 45% due to non-ischaemic aetiology (e.g. idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy) or IHF patients with LVEF ≥ 45% were excluded. Patients who were without any follow-up since discharge or who were without creatinine and/or haemoglobin data at baseline were excluded for the current analyses.

Data collection

Baseline data, including demographics, vital sign at admission, co-morbid conditions, and echocardiographic report, were extracted from the electronic health record of Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital. Fasting venous blood was drawn for evaluation of lipid profiles and fasting plasma glucose at the second day after admission. Non-fasting venous blood upon admission was drawn for evaluation of haemoglobin concentration, creatinine, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (Hs-CRP), high-sensitivity cardiac troponin-T (Hs-cTNT), and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). Serum creatinine was used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the Modified Diet of Renal Disease formula,18 and eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 was defined as CKD. According to the Chinese criteria, anaemia was defined as haemoglobin concentration < 120 g/L for men and <110 g/L for women.19 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by body weight in kilograms divided by height in squared metres, and BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 was defined as obesity according to the World Health Organization criterion for the Asian populations.20 In-hospital treatment (coronary stenting, intravenous inotrope, and intravenous diuretic) and medication prescribed at discharge were extracted from the electronic health record. Data were entered to the Excel spreadsheet by study investigators.

Follow-up and clinical endpoint

Follow-up was performed after discharge by study investigators using phone call interview. Patients were followed until the occurrence of clinical endpoint, which was defined as all-cause mortality. In brief, due to the unavailability of adjudication for the exact reason of death, all-cause mortality was used in the current analyses. Length of follow-up was calculated using the date of the last follow-up or the date of death minus the date of discharge from index hospitalization. Among six patients who died during index hospitalization, the duration of follow-up was calculated as the date of death minus the date of admission. Patients were followed through 15 October 2020.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables were presented as number and proportion. Comparisons of continuous variables were performed using the Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, and comparisons of categorical variables were performed using χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Differences in baseline characteristics were examined between anaemia versus non-anaemia according to CKD status.

To examine factors associated with anaemia among CKD and non-CKD patients, respectively, univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed. In the univariate analysis, factors with a P-value < 0.1 were entered into the multivariable analyses. Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported. Pearson correlation analysis was further performed to analyse the relationship between haemoglobin concentration and eGFR among CKD and non-CKD patients, respectively.

Incidence rate of all-cause mortality was calculated by dividing the number of events by person-years of follow-up accrued. Differences in the incidence rate were examined between anaemia and non-anaemia according to CKD status. Incidence rate ratio and associated 95% CI were reported. Survival analyses were further performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in cumulative incidence rate were compared with a log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were performed to evaluate the association between anaemia and all-cause mortality among CKD and non-CKD patients, respectively, with stepwise adjustment for covariates including age and sex (Model 1), co-morbid conditions, LVEF, and Hs-CRP (Model 2), in-hospital treatment (Model 3), and medication prescribed at discharge (Model 4). Hazard ratio and associated 95% CI were reported. To examine whether there was a non-linear relationship between haemoglobin concentration and all-cause mortality risk, the restricted cubic spline was performed according to CKD status. A P-value < 0.05 was defined as statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

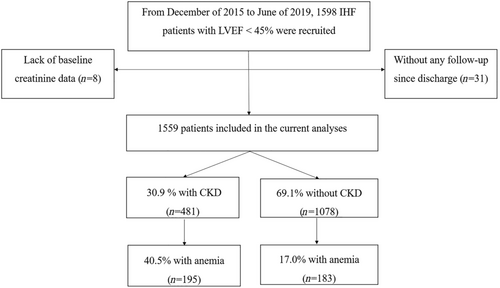

During the study period, 1598 IHF patients with LVEF < 45% were recruited for the cohort study (Figure 1). Among them, 31 patients were without any follow-up since discharge and eight patients lacked baseline creatinine data. A total of 1559 patients were included for the current analysis. The mean age was 63.5 ± 11.0 years, 85.8% were men, the mean eGFR was 70.6 ± 23.1 mL/min/1.73 m2, and the mean haemoglobin concentration was 131.9 ± 19.1 g/L. The prevalence of CKD was 30.9%, with 21 patients (1.3%) on haemodialysis. The prevalence of anaemia in the CKD and non-CKD groups was 40.5% and 17.0%, respectively. Among the included patients, 1183 (75.9%) had an LVEF ≤ 40%, with 371 (77.1%) and 812 (75.3%) in the CKD and non-CKD groups (P-value = 0.44), respectively.

Baseline characteristics comparisons between anaemia and anaemia according to chronic kidney disease status

In the CKD group (Table 1), anaemic patients were older (70.2 ± 10.2 vs. 65.7 ± 10.4 years), more likely to be women, and had lower BMI and diastolic blood pressure. More than 60% of anaemic and non-anaemic patients hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome (62.1% vs. 60.1%) and the rest for HF. Anaemic patients were less likely to smoke and have dyslipidaemia but more likely to have diabetes mellitus. Anaemic patients had lower eGFR (39.5 ± 15.8 vs. 49.1 ± 10.3 mL/min/1.73 m2), higher Hs-cTNT and NT-proBNP, and higher LVEF (35.3 ± 6.8% vs. 33.7 ± 7.7%). The percentage of patients with LVEF ≤ 40% was comparable in the CKD and non-CKD groups (73.9% vs. 79.4%). Approximately 60% of anaemic and non-anaemic patients received coronary stenting (58.5% vs. 66.4%), and anaemic patients were more likely to receive intravenous diuretic (55.9% vs. 43.7%) during hospitalization and were less likely to be prescribed aspirin, ticagrelor, and renin-angiotensin-system inhibitor at discharge.

| Variables | CKD (n = 481) | Non-CKD (n = 1078) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaemia (n = 195) | Non-anaemia (n = 286) | P-value | Anaemia (n = 183) | Non-anaemia (n = 895) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 70.2 ± 10.2 | 65.7 ± 10.4 | <0.0001 | 65.1 ± 10.2 | 61.0 ± 10.6 | <0.0001 |

| Male, n (%) | 126 (64.6) | 255 (89.2) | <0.0001 | 136 (74.3) | 821 (91.7) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.6 ± 3.4 | 24.1 ± 3.5 | 0.0005 | 22.7 ± 3.3 | 23.9 ± 3.2 | 0.0002 |

| Vital sign at admission | ||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 128 ± 21 | 126 ± 21 | 0.21 | 121 ± 20 | 126 ± 19 | 0.003 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 71 ± 12 | 76 ± 14 | <0.0001 | 71 ± 12 | 76 ± 12 | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 80 ± 15 | 80 ± 16 | 0.73 | 81 ± 13 | 79 ± 14 | 0.07 |

| Reason for admission | ||||||

| STEMI, n (%) | 22 (11.3) | 33 (11.5) | 0.93 | 33 (18.0) | 156 (17.4) | 0.85 |

| Non-STEMI, n (%) | 21 (10.8) | 19 (6.6) | 0.11 | 18 (9.8) | 57 (6.4) | 0.09 |

| Unstable angina, n (%) | 78 (40.0) | 120 (42.0) | 0.67 | 79 (43.2) | 426 (47.6) | 0.27 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 71 (36.4) | 113 (39.5) | 0.49 | 49 (26.8) | 229 (25.6) | 0.74 |

| Others, n (%) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0.16 | 4 (2.2) | 2 (3.0) | 0.54 |

| Co-morbid conditions | ||||||

| Smoking, n (%) | 18 (9.2) | 60 (21.0) | 0.003 | 35 (19.1) | 256 (28.6) | 0.03 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 8 (4.1) | 18 (6.3) | 0.30 | 6 (3.3) | 42 (4.7) | 0.40 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 120 (61.5) | 182 (63.6) | 0.64 | 80 (43.7) | 426 (47.6) | 0.34 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 94 (48.2) | 93 (32.5) | 0.0005 | 63 (34.4) | 266 (29.7) | 0.21 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 104 (53.3) | 205 (71.7) | <0.0001 | 88 (48.1) | 582 (65.0) | <0.0001 |

| COPD, n (%) | 21 (10.8) | 21 (7.3) | 0.19 | 13 (7.1) | 60 (6.7) | 0.84 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 11 (5.6) | 19 (6.6) | 0.66 | 6 (3.3) | 62 (6.9) | 0.06 |

| Prior stroke/TIA, n (%) | 19 (9.7) | 20 (7.0) | 0.28 | 24 (13.1) | 60 (6.7) | 0.003 |

| Prior MI, n (%) | 70 (35.9) | 121 (42.3) | 0.16 | 60 (32.8) | 312 (34.9) | 0.59 |

| Prior PCI, n (%) | 113 (58.0) | 170 (59.4) | 0.74 | 98 (53.6) | 529 (59.1) | 0.17 |

| Prior CABG, n (%) | 2 (1.0) | 7 (2.5) | 0.26 | 2 (1.1) | 20 (2.2) | 0.32 |

| Laboratory | ||||||

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 104.0 ± 13.4 | 139.1 ± 13.6 | <0.0001 | 109.4 ± 10.6 | 140.3 ± 12.5 | <0.0001 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 6.8 ± 3.5 | 6.1 ± 2.4 | 0.02 | 5.8 ± 2.1 | 6.1 ± 2.3 | 0.30 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.15 ± 1.20 | 4.52 ± 1.30 | 0.0001 | 4.14 ± 1.62 | 4.44 ± 1.23 | 0.005 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.67 ± 0.89 | 2.98 ± 0.99 | 0.0005 | 2.73 ± 1.27 | 2.91 ± 0.95 | 0.03 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.94 ± 0.25 | 0.94 ± 0.24 | 0.95 | 0.90 ± 0.25 | 0.95 ± 0.23 | 0.01 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L)a | 1.29 (0.96–1.75) | 1.45 (1.03–2.02) | 0.02 | 1.10 (0.79–1.45) | 1.31 (1.01–1.80) | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.0006 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 39.5 ± 15.8 | 49.1 ± 10.3 | <0.0001 | 81.9 ± 16.8 | 82.0 ± 16.5 | 0.94 |

| Hs-CRP (mg/L)a | 8.3 (2.5–26.1) | 5.4 (1.9–13.8) | 0.11 | 10.5 (2.2–31.6) | 3.9 (1.1–11.4) | <0.0001 |

| Hs-cTNT (pg/mL)a | 78 (34–514) | 40 (21–134) | <0.0001 | 49 (20–298) | 29 (16–173) | 0.01 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL)a | 4952 (2247–12 692) | 1925 (844–4568) | <0.0001 | 2229 (1000–4156) | 1124 (471–2419) | <0.0001 |

| Echocardiographic indices | ||||||

| LVPW (mm) | 9.3 ± 1.9 | 9.1 ± 1.9 | 0.23 | 9.1 ± 1.7 | 9.2 ± 1.8 | 0.58 |

| IVS (mm) | 9.8 ± 2.0 | 9.8 ± 2.3 | 0.98 | 9.4 ± 1.9 | 9.4 ± 2.1 | 0.71 |

| LVESD (mm) | 46.0 ± 8.3 | 49.3 ± 10.2 | 0.0002 | 45.4 ± 9.2 | 47.6 ± 9.1 | 0.003 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 57.5 ± 7.7 | 60.2 ± 8.8 | 0.0005 | 57.6 ± 7.7 | 59.1 ± 8.0 | 0.02 |

| LA diameter (mm) | 41.0 ± 6.3 | 41.2 ± 6.7 | 0.72 | 40.1 ± 6.0 | 40.3 ± 6.1 | 0.62 |

| LVEF (%) | 35.3 ± 6.8 | 33.7 ± 7.7 | 0.02 | 35.6 ± 6.4 | 35.2 ± 6.7 | 0.51 |

| LVEF ≤ 40%, n (%) | 144 (73.9) | 227 (79.4) | 0.16 | 141 (77.1) | 671 (75.0) | 0.55 |

| In-hospital treatment | ||||||

| Coronary stenting, n (%) | 114 (58.5) | 190 (66.4) | 0.08 | 139 (76.0) | 634 (70.8) | 0.16 |

| IV inotrope, n (%) | 35 (18.0) | 48 (16.8) | 0.74 | 21 (11.5) | 96 (10.7) | 0.77 |

| IV diuretic, n (%) | 109 (55.9) | 125 (43.7) | 0.009 | 65 (35.5) | 257 (28.7) | 0.07 |

| Medication prescribed at discharge | ||||||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 156 (80.0) | 255 (89.2) | 0.005 | 158 (86.3) | 822 (91.8) | 0.02 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 156 (80.0) | 210 (73.4) | 0.10 | 136 (74.3) | 660 (73.7) | 0.87 |

| Ticagrelor, n (%) | 10 (5.1) | 30 (10.5) | 0.04 | 32 (17.5) | 133 (14.9) | 0.37 |

| Statins, n (%) | 181 (92.8) | 267 (93.4) | 0.82 | 177 (96.7) | 860 (96.1) | 0.68 |

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 157 (80.5) | 233 (81.5) | 0.79 | 152 (83.1) | 776 (86.7) | 0.19 |

| RASi, n (%) | 122 (62.6) | 205 (71.7) | 0.04 | 121 (66.1) | 649 (72.5) | 0.08 |

| RANI, n (%) | 3 (1.5) | 7 (2.5) | 0.49 | 4 (2.2) | 31 (3.5) | 0.37 |

| MRA, n (%) | 110 (56.4) | 163 (57.0) | 0.90 | 90 (49.2) | 426 (47.6) | 0.70 |

| Loop diuretic, n (%) | 121 (62.1) | 154 (53.9) | 0.07 | 84 (45.9) | 383 (42.8) | 0.44 |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 21 (10.8) | 29 (10.1) | 0.82 | 12 (6.6) | 49 (5.5) | 0.56 |

| CCB, n (%) | 40 (20.5) | 40 (14.0) | 0.06 | 7 (3.8) | 69 (7.7) | 0.06 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 20 (10.3) | 21 (7.3) | 0.26 | 15 (8.2) | 54 (6.0) | 0.28 |

| Oral hypoglycaemics, n (%) | 58 (31.5) | 67 (25.1) | 0.13 | 55 (30.7) | 226 (26.6) | 0.26 |

| Oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 11 (5.6) | 24 (8.4) | 0.25 | 8 (4.4) | 67 (7.5) | 0.13 |

- BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; Hs-cTNT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin-T; IVS, intra-ventricular septum; LA, left atrial; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic diameter; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; non-STEMI, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RANI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; RASi, renin-angiotensin-system inhibitor; SBP, systolic blood pressure; STEMI, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; TC, total cholesterol; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

- a Presented as median (interquartile range).

In the non-CKD group, anaemic patients were older (65.1 ± 10.2 vs. 61.0 ± 10.6 years), more likely to be women, and had lower BMI and systolic and diastolic blood pressure. More than 70% of anaemic and non-anaemic patients hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome (71.0% vs. 71.4%) and the rest for HF. Anaemic patients were less likely to smoke and have dyslipidaemia but more likely to have prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack. Anaemic patients had higher Hs-CRP, Hs-cTNT, and NT-proBNP. There were no differences in LVEF (35.6 ± 6.4% vs. 35.2 ± 6.7%) and the percentage of patients with LVEF ≤ 40% (77.1% vs. 75.0%) between the CKD and non-CKD groups. More than 70% of anaemic and non-anaemic patients received coronary stenting (76.0% vs. 70.8%), and the percentage of patients received intravenous diuretic during hospitalization was numerously higher in the anaemic group (35.5% vs. 28.7%; P-value = 0.07). Anaemic patients were less likely to be prescribed aspirin, and the percentage of anaemic patients received renin-angiotensin-system inhibitor was numerously lower (66.1% vs. 72.5%; P-value = 0.08).

Factors associated with anaemia according to chronic kidney disease status

In the CKD group (Table 2), in the univariate analysis, factors associated with anaemia included age, sex, BMI, eGFR, Hs-CRP, and diabetes mellitus. After multivariable regression analyses, factors remained associated with anaemia included sex, eGFR, and diabetes mellitus. In specific, per 1 mL/min/1.73 m2 decrease in eGFR was associated with 6% (95% CI: 4–9%; P-value < 0.0001) higher odds of having anaemia.

| Variables | CKD | Non-CKD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariable | Univariate | Multivariable | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | <0.0001 | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 0.12 | 1.04 (1.02–1.056) | <0.0001 | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.07 |

| Men versus women | 0.22 (0.14–0.36) | <0.0001 | 0.35 (0.15–0.80) | 0.01 | 0.26 (0.17–0.39) | <0.0001 | 0.30 (0.15–0.58) | 0.0004 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2 increase) | 0.88 (0.82–0.95) | 0.0006 | 0.93 (0.83–1.03) | 0.14 | 0.88 (0.82–0.94) | 0.0003 | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 0.13 |

| eGFR (per 1 mL/min/1.73 m2 decrease) | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) | <0.0001 | 1.06 (1.04–1.09) | <0.0001 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.94 | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.37 |

| Hs-CRP (per 1 mg/L increase) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.05 | 1.003 (0.99–1.01) | 0.57 | 1.006 (1.001–1.011) | 0.003 | 1.01 (1.006–1.02) | 0.0005 |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | 0.91 (0.63–1.33) | 0.64 | N/A | 0.86 (0.62–1.18) | 0.34 | N/A | ||

| Diabetes mellitus (yes vs. no) | 1.93 (1.33–2.81) | 0.0006 | 2.11 (1.09–4.09) | 0.03 | 1.24 (0.89–1.74) | 0.21 | N/A | |

| Atrial fibrillation (yes vs. no) | 0.84 (0.39–1.81) | 0.66 | N/A | 0.46 (0.19–1.07) | 0.07 | 0.85 (0.29–2.48) | 0.77 | |

| COPD (yes vs. no) | 1.52 (0.81–2.87) | 0.19 | N/A | 1.06 (0.57–1.98) | 0.84 | N/A | ||

- BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; N/A, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

In the non-CKD group, in the univariate analysis, factors associated with anaemia included age, sex, BMI, and Hs-CRP. After multivariable regression analyses, factors remained associated with anaemia included sex and Hs-CRP, and eGFR alteration was not associated with anaemia.

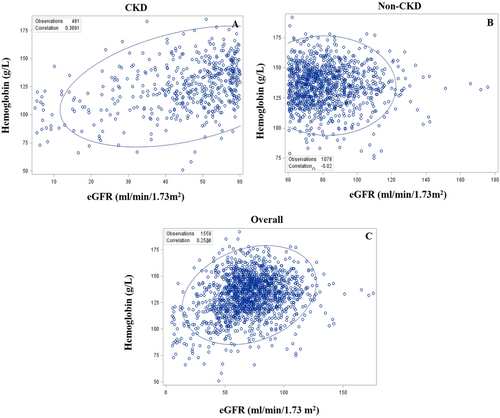

Relationship between estimated glomerular filtration rate and haemoglobin concentration according to chronic kidney disease status

In the CKD group (Figure 2), eGFR was positively correlated with haemoglobin concentration, with a correlation coefficient of 0.39 (P < 0.0001), while in the non-CKD group (Figure 2), eGFR was not correlated with haemoglobin concentration (P = 0.51). When CKD and non-CKD patients were combined as a whole, eGFR was positively correlated with haemoglobin concentration (correlation coefficient of 0.25; P < 0.0001; Figure 2).

All-cause mortality comparisons between anaemia and non-anaemia according to chronic kidney disease status

In the CKD group (Table 3), during a median follow-up of 2.1 years, 60 anaemic and 65 non-anaemic patients died, with an incidence rate of 15.4 and 10.8 per 100 person-years, respectively. The incidence rate ratio was 1.42 (95% CI: 1.00–2.02; P-value = 0.05). In the non-CKD group, during a median follow-up of 2.1 years, 35 anaemic and 102 non-anaemic patients died, with an incidence rate of 9.8 and 5.5 per 100 person-years, respectively. The incidence rate ratio was 1.78 (95% CI: 1.20–2.59; P-value = 0.005).

| Follow-up (years) | Median follow-up (years) | Event (n) | Incidence rate (per 100 person-years) | Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKD (n = 481) | Anaemia (n = 195) | 389.4 | 2.1 (0.7–3.2) | 60 | 15.4 | 1.42 (1.00–2.02) | 0.05 |

| Non-anaemia (n = 286) | 599.8 | 2.2 (0.9–3.2) | 65 | 10.8 | |||

| Non-CKD (n = 1078) | Anaemia (n = 183) | 355.3 | 2.1 (0.9–3.0) | 35 | 9.8 | 1.78 (1.20–2.59) | 0.005 |

| Non-anaemia (n = 895) | 1842.4 | 2.1 (1.2–3.0) | 102 | 5.5 |

- CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

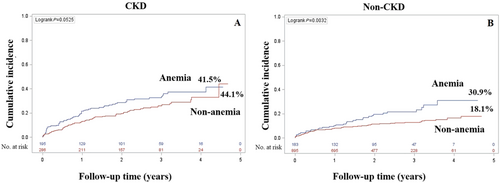

In the CKD group (Figure 3), during a median follow-up of 2.1 years, the cumulative incidence rate of all-cause mortality among anaemic and non-anaemic patients was 41.5% and 44.1%, respectively (P-value = 0.05). In the non-CKD group (Figure 3), during a median follow-up of 2.1 years, the cumulative incidence rate of all-cause mortality in anaemic and non-anaemic patients was 30.9% and 18.1%, respectively (P-value < 0.0001).

Association between anaemia and all-cause mortality according to chronic kidney disease status

In the CKD group (Table 4), in the unadjusted model, the presence of anaemia was associated with 1.41-fold higher hazard (95% CI: 1.00–2.01; P-value = 0.05) of all-cause mortality. After stepwise adjusting for covariates, the presence of anaemia was associated with 1.75-fold higher hazard (95% CI: 0.95–3.20) of all-cause mortality although without statistical significance (P-value = 0.07). The interaction between anaemia and CKD for all-cause mortality was presented in Supplement Table 1.

| CKD | Non-CKD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaemia versus non-anaemia | Anaemia versus non-anaemia | |||

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Unadjusted | 1.41 (1.00–2.01) | 0.05 | 1.77 (1.20–2.60) | 0.004 |

| Model 1 | 1.40 (0.97–2.03) | 0.07 | 1.55 (1.04–2.30) | 0.04 |

| Model 2 | 1.81 (1.00–3.29) | 0.05 | 1.94 (1.01–3.71) | 0.04 |

| Model 3 | 1.77 (0.98–3.19) | 0.06 | 1.95 (1.01–3.74) | 0.04 |

| Model 4 | 1.75 (0.95–3.20) | 0.07 | 1.90 (0.98–3.69) | 0.06 |

- CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HR, hazard ratio.

- Model 1: adjusted for age and sex. Model 2: adjusted for Model 1 plus body mass index, smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke/transient ischaemic attack, prior myocardial infarction, admission for heart failure, admission for acute coronary syndrome, left ventricular ejection fraction, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Model 3: adjusted for Model 1, Model 2 plus coronary stenting, intravenous inotrope, and intravenous diuretic. Model 4: adjusted for Model 1, Model 2, Model 3 plus aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, statins, beta-blocker, renin-angiotensin-system inhibitor, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

In the non-CKD group, in the unadjusted model, the presence of anaemia was associated with 1.77-fold higher hazard (95% CI: 1.20–2.60) of all-cause mortality. Before adjusting for medication prescribed at discharge, the presence of anaemia remained significantly associated with all-cause mortality. After further adjusting for medication prescribed at discharge, the presence of anaemia was associated with 1.90-fold higher hazard (95% CI: 0.98–3.69) of all-cause mortality although without statistical significance (P-value = 0.06). Association between anemia and all-cause mortality with adjustment for CKD or eGFR were shown in Supplement Table 2.

Association between haemoglobin concentration and all-cause mortality according to chronic kidney disease status

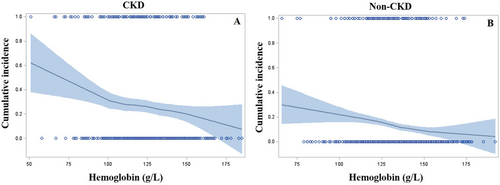

In the CKD group (Figure 4), the cumulative incidence rate of all-cause mortality was increased with decreasing haemoglobin concentration. Notably, when haemoglobin concentration was below 100 g/L, the all-cause mortality risk was increased steeply. There was a similar trend between haemoglobin concentration and all-cause mortality risk in the non-CKD group (Figure 4); however, no inflection point was observed.

Discussion

The main findings of the current study are that (i) among IHF patients with CKD, decreasing eGFR was associated with increasing prevalence of anaemia, while this relationship was not observed among IHF patients without CKD; (ii) in the CKD group, anaemic patients had a borderline higher crude risk of all-cause mortality compared with non-anaemic counterparts, while in the non-CKD group, anaemic patients had a significantly higher crude risk of all-cause mortality compared with non-anaemic counterparts; (iii) among CKD and non-CKD patients, after adjusting for multiple covariates, the presence of anaemia was associated with a borderline higher risk of all-cause mortality; and (iv) among CKD patients, it appeared that the risk of all-cause mortality increased prominently when haemoglobin concentration was below 100 g/L, which was not observed among patients without CKD.

Anaemia is a common complication of CKD, and the presence of anaemia appears to add another layer of complexity to the relationship between CKD and HF.21, 22 To examine the exact influences of CKD-related anaemia on all-cause mortality, patients were specifically divided into the CKD and non-CKD groups based on the eGFR value in the current analysis. We first evaluated whether the relationship between eGFR and prevalent anaemia was varied by CKD status. The results indicated that among CKD patients, decreased eGFR was associated with increased odds of anaemia even after adjusting for multiple covariates, including age, sex, BMI, Hs-CRP, and diabetes mellitus. Nonetheless, among patients without CKD, there was no relationship between eGFR alteration and prevalent anaemia. Positive correlation between eGFR and haemoglobin concentration among CKD patients further supports the importance of CKD-related mechanisms to the development of anaemia. Indeed, during CKD progression, insufficient synthesis of erythropoietin in the renal peritubular cells and impaired iron utilization due to CKD-related chronic inflammation contribute to the development of anaemia in CKD patients.13, 14 It is noted that the prevalence of anaemia among non-CKD patients was approximately 17.0%. As shown in the regression analysis, decreased eGFR was not associated with prevalent anaemia among non-CKD patients, suggesting that differential mechanisms might underline anaemia development among non-CKD patients. Indeed, as indicated in Table 2, factors that were associated with anaemia among non-CKD patients included female sex and increased Hs-CRP level. Mechanically, chronic inflammation is associated with impaired iron absorption and utilization, and reduced erythrocytes generation, which in turn causes anaemia.23 Taken together, the independent relationship between decreased eGFR and prevalent anaemia among CKD patients provides foundation to explore the prognostic impacts of CKD-related anaemia on IHF populations.

Studies have demonstrated that anaemia associated with CKD is an independent risk factor for mortality among HF patients15-17; and among CKD patients, at all levels of eGFR, the presence of anaemia portends a worse prognosis and is associated with a higher mortality rate compared with non-anaemic patients.24 In the current study, among CKD patients, the incidence rate of all-cause mortality was borderline higher between anaemia and non-anaemia. In addition, the presence of anaemia was also associated with 1.75-fold higher hazard of all-cause mortality although without statistical significance. Nonetheless, considering the adverse effects of anaemia and CKD on cardiovascular system, it is reasonable to speculate that CKD patients with anaemia might have a higher mortality risk than their non-anaemic counterparts. The lack of statistical significance of the current analysis might be partly due to insufficient statistical power. On the other hand, one might speculate that the presence of anaemia might reflect the severity of underlying CKD, and therefore, anaemia might serve as a marker rather than a maker to increase all-cause mortality risk among CKD populations.25, 26 Further studies with a large sample size are needed to examine this hypothesis.

Among non-CKD patients, the incidence and cumulative incidence rate of all-cause mortality was significantly higher among anaemic versus non-anaemic patients, which was consistent to prior reports.26, 27 These findings indicated that anaemia might play a direct role on increasing mortality risk for IHF patients without CKD. Indeed, anaemia-related cardiac structural and functional alterations (e.g. left ventricular hypertrophy and increased cardiac output), reduced coronary perfusion, and decreased oxygen supply to peripheral tissue have been proposed to explain the adverse prognosis for anaemic individuals.14, 28, 29 Nonetheless, in the current study, anaemia was not an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality after adjusting for medication prescribed at discharge. Notably, anaemic patients were older, more likely to be women, and had a higher degree of chronic inflammation, cardiac injury, and cardiac stress, demonstrating a high mortality risk population. Nonetheless, the use of guideline-recommended medication such as aspirin and renin-angiotensin-system inhibitor was lower in these anaemic patients. These findings confirm and extend prior studies by demonstrating that among IHF patients, the presence of anaemia was associated with a significantly higher all-cause mortality risk and increased utilization of guideline-recommended medication might mitigate the mortality risk associated with anaemia. Further studies are needed to confirm this speculation.

Anaemia has been recognized as an independent risk factor for mortality among HF patients; however, the optimal range of haemoglobin concentration that might be associated with the lowest mortality risk is undetermined.30, 31 In addition, studies have suggested a U-shaped relationship between haemoglobin concentration and all-cause mortality.27, 32 Therefore, one question that clinicians might wonder is at what level of haemoglobin concentration the mortality risk would increase prominently. This question is clinically relevant as it might indicate that below a certain level of haemoglobin concentration, the mortality risk would increase significantly, and blood transfusion might result in a greater survival benefit. Results of the current study suggested that among CKD patients, the risk of all-cause mortality was increased prominently when haemoglobin concentration was below 100 g/L, while among patients without CKD, no specific inflection point was identified. The reasons to explain the differential observations are speculative. Compared with non-CKD patients, CKD patients have a greater co-morbid burden, which might lead them to be more vulnerable to even mild reduction of haemoglobin concentration. On the other hand, CKD plus reduced haemoglobin concentration might exert synergistic effects on increasing all-cause mortality risk. Future studies are needed to corroborate the current findings and to evaluate whether maintaining haemoglobin concentration above 100 g/L would attenuate the mortality risk in a favourable way.

Limitations

There are several limitations that should be mentioned. First, the observational nature of the current study limited us to draw any causal relationship between anaemia and all-cause mortality among IHF patients with and without CKD. Second, lack of statistical significance of the current findings might be partly due to insufficient statistical power. Third, we did not assess the impacts of anaemia and CKD on cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality, respectively, due to lack of adjudication for the exact reason of death. Fourth, the current study did not collect data on haemoglobin and creatinine change and guideline-recommended medication use during follow-up, which could not allow us to adjust for these time-varying covariates. Fifth, we have only included a small number of patients on haemodialysis (1.3%), and these findings should not be extrapolated to those on maintained haemodialysis. Sixth, we only recruited IHF patients with LVEF < 45%, and therefore, these findings should not be generalized to those with non-IHF and/or with LVEF ≥ 45%. Seventh, less than 20% of participants were female, and it should be cautious to interpret the current findings for female patients. Last but not the least, we did not capture the data on blood transfusion and/or iron supplement for anaemic patients during index hospitalization and follow-up. Therefore, we were unsure whether these unmeasured confounding factors would influence the overall findings of the current study. In addition, we did not collect data on serum iron, folate acid, vitamin B12, and erythropoietin concentration, which limited us to discriminate the aetiologies of anaemia. Further studies are needed to clarify whether the aetiology of anaemia would modify the relationship between anaemia and all-cause mortality.

Conclusions

In conclusion, among IHF patients, the presence of anaemia was associated with a borderline higher risk of all-cause mortality in the CKD group and a significant higher risk of all-cause mortality in the non-CKD group. Among CKD patients, when haemoglobin concentration was below 100 g/L, all-cause mortality risk was increased steeply. These findings underscore the importance to assess mortality risk and manage anaemia among IHF patients according to renal function status.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate very much the patients and their family and the nurses for support to the current study.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

The current study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1301202), Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital Clinical Research Fund (Y012018085), and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Coronary Artery Disease Prevention Fund (Z02207016).