Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-assisted emergency percutaneous treatment of left ventricular assist device graft occlusion

Abstract

End-stage heart failure is more often treated with Implantable left ventricular assist device (LVAD), even if the prolonged use may increase the risk of complications. In this case, a 51-year-old male patient presented to our emergency department showing acute heart failure signs and symptoms and a dramatic reduction of LVAD flow. Laboratory tests ruled out significant haemolysis, usually associated with pump thrombosis. The echocardiogram and the computed tomography were not able to clarify the correct diagnosis. We immediately placed a veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, followed by a selective retrograde angiography of the pump. The images showed stenosis of the LVAD-outflow graft, suggesting a twist. Through a hand-made J-tip guidewire, we performed multiple dilatations of the occlusion using peripheral balloons. Finally, we implanted an aortic coarctation covered-stent, re-establishing an adequate cardiac output to the patient. Our case indicates that catheter-based approach in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation assistance provides an important therapeutic alternative to treat outflow graft stenosis, especially in the case of acutely unstable patient.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a growing pathology affecting at least 26 million of people worldwide, and this is expected to increase by 25% by 2030.1 Despite improvements in pharmacological therapy and pacing, 0.5–5% of patients develop chronic advanced HF, with a 1 year mortality of 25–50%.2 Heart transplantation should be the gold standard for refractory HF, but shortage of donors could be a limitation. For this reason, end-stage HF is more often treated with implantable left ventricular assist device (LVAD). Unfortunately, the prolonged use of this devices increases the risk of developing complications, such as right ventricular failure, LVAD thrombosis, device-related infections or neurological complications (from transient ischemic attack to a severe life-threatening stroke),3 and aortic regurgitation.4 Outflow graft obstruction is a very rare, but fatal complication that may occur within an average of 3 years after an LVAD implantation5 and can lead to a low cardiac output syndrome. This may require surgical intervention,6 but in those cases, the initial endovascular approach can lead to an immediate flow recovery.

Case report

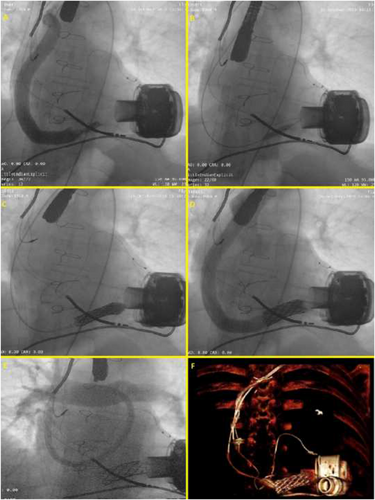

A 51-year-old male patient presented to our emergency department showing chest pain and dyspnoea. He had a history of end-stage familial dilated cardiomyopathy, which was treated 24 months before with a centrifugal pump (HeartMate 3™ Left Ventricular Assist Device, Abbott) as a bridge to transplantation, with a complete functional recovery (NYHA Class I). The clinical examination showed an acute HF with pulmonary oedema; his trans-thoracic echocardiogram showed a worsened dilatation of the left ventricle with the increased opening movement of aortic valve leaflets and of aortic regurgitation. LVAD parameters showed a normal estimated flow with normal pump-power and pulsatility index, while the haemodynamic ramp tests failed to reduce left ventricular end-diastolic diameter. Laboratory tests (LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) levels, haematocrit/haemoglobin, haptoglobin, total bilirubin, and INR (International Normalized Ratio)) ruled out clinically significant haemolysis, usually associated with pump thrombosis.7 Computed tomography (CT) excluded the external compression of the LVAD outflow graft. We immediately started with a pharmacological therapy with a high dose of furosemide, that is, and sodium nitroprusside, which brought to a mild clinical improvement, as well as to a reduction of the LV chamber dimensions. Unfortunately, 48 h later, his health condition rapidly worsened, resulting in hypotension with a systolic blood pressure of 80 mmHg, evidence of tissue hypoperfusion with increased lactate levels of 4.6 mmol/L, and a fall in urine output, developing the clinical picture of the cardiogenic shock (Stage C-Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) classification8). At the same time, a sudden dramatic reduction of LVAD flow occurred with multiple low-flow alarms. Given the refractory cardiogenic shock, the patient was immediately brought to our cath-lab. A peripheral veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was placed through open surgical cannulation of the common right femoral artery and vein by cardiac surgeons. Because we suspected occlusive stenosis of the LVAD outflow graft, we placed a 14-French sheath in the common left femoral artery under ultrasound guidance, which would have allowed us to implant a stent corresponding to the measure of the outflow device. Afterwards, a pigtail 6 F diagnostic catheter with a 0.035 inch guidewire was used to perform a selective retrograde angiography of the pump. The result showed images suggesting a diagnosis of outflow graft stenosis (Figure 1) as a consequence of a twist (supporting information, Video S1). Due to the high risk of mortality and morbidity from a surgical treatment, we agreed with the cardiac surgeons in the ‘Heart Team’ to perform an emergency percutaneous intervention of the LVAD graft stenosis. We started with a 0.035 inch super-stiff guidewire (EMERALD, Amplatz Super Stiff™ J curve-Tip, 260 cm; Cordis, Ireland), with a J-tip self-modified, to allow a landing near the centrifugal pump. At this point, we performed multiple dilatations with increasing diameter peripheral balloons (Figure 1), starting with 8.0 × 40 mm, arriving at 12 × 40 mm (eV3 EverCross, 0.035 OTW PTA Dilatation Catheter, USA). Later, thanks to a more supporting guidewire, (Amplatz Super Stiff J curve-tip 0.035, 260 cm, Boston Scientific), we performed a dilatation with a balloon-expandable 34 × 16 mm (CP STENT™ NuMED, Inc) covered stent, commonly used for the treatment of aortic coarctation (Figure 1). The delivery of the stent resulted in immediate evidence of blood-flow improvement through the outflow graft (Video S2) into the Aorta, re-establishing an adequate cardiac output to the patient (Figure 1). Consequently, the arterial cannula of the ECMO was explanted. Due to severe right ventricular failure, ECMO venous cannula was left into the right atrium and a 15-French jugular venous cannula (Bio-Medicus™ NextGen, Medtronic) was percutaneously placed in the pulmonary trunk, through the right internal jugular vein (Figure 1). A right ventricular assist device (RVAD) and optimal blood oxygenation was realized. Having the haemodynamic status being re-established thanks to a simultaneous LVAD therapy and a temporary RVAD, the patient was brought to the intensive care unit. After a few days, a computed tomography-scan (Figure 1) confirmed the patency of the implanted stent. The patient was explanted from RVAD support and removed from the intensive care unit in 1 week. One month later, we dismissed the patient in NYHA Class I with the analysis of the LVAD persistently normal and no further alarms. In our centre, all the patients with an LVAD perform a follow-up every month, with clinical exam and pump parameters analysis. This particular case was closely checked every 2 weeks, and his clinical condition had remained stable.

Discussion and conclusion

Obstruction of LVAD outflow graft is a rare and potentially fatal complication with unknown incidence9 and a very challenging diagnosis for clinicians. From our experience, the laboratory markers, such as LDH levels, haematocrit/haemoglobin, haptoglobin, total bilirubin, and INR, represent the first alteration in case of thrombosis of the LVAD outflow. CT images may be very helpful to distinguish external compression as opposed to thrombus within the graft, but when diagnosis is not evident, a selective retrograde angiography of the device becomes fundamental. Management of LVAD outflow graft occlusion still remains unclear. Even if there are no specific guidelines, surgical repair seems to be the right strategy—when feasible—especially if a mechanical issue, such as kinking of the outflow graft, may occur.10 Because percutaneous therapies have evolved, a minimally invasive approach has recently become prominent. Although further prospective randomized studies are needed to determine the durability of the catheter-based approach compared with surgery, outflow graft stenting appears to be a safer and more effective procedure, especially in the setting of an acutely unstable patient. It provides an important therapeutic alternative to treat outflow graft stenosis and is associated with low overall mortality6 avoiding re-sternotomy. In this case, the use of ECMO allowed us to perform a percutaneous intervention in a state of relative haemodynamic stability of the patient and in quite safer conditions. This approach could represent the ‘standard of care’ in this type of complications in the future. Moreover, from a forensic point of view, the patient's extremely serious condition legitimized the heart team to immediate intervention, in order to improve the patient's health state, even if without explicit formal patient's consent. In this complex scenario, the support of the entire heart team and a shared-making decision approach are fundamental to the success of the procedure.