How many types of circulation can a boy have during his life? A case of aortic stenosis with a borderline left ventricle

Abstract

Severe aortic stenosis can be accompanied by various degrees of left ventricular underdevelopment. The assessment whether a borderline-sized left ventricle can or cannot support the systemic circulation is crucial. The decision-making still remains challenging. We present a case that illustrates that the development of haemodynamic parameters can be difficult to estimate, even in the long term. The patient went from biventricular to univentricular circulation and back and could finally be palliated by heart transplantation. Modern technology including long-term mechanical cardiac support as a bridge to candidacy and drug therapy for pulmonary hypertension were vital to successfully combat a previously lethal disease.

Introduction

Newborns with borderline left ventricles (LVs) present a specific challenge—the assessment whether the LV can support the systemic cardiac output is crucial for therapy planning.1, 2 In critical aortic stenosis, especially in the setting of initial LV dysfunction, the decision-making can be challenging despite established scoring systems.3-5 We present a case that illustrates how long-term development of haemodynamic parameters can be difficult to estimate.

Case report

Critical aortic stenosis with dysplastic bicuspid aortic valve was diagnosed in a male newborn. The LV was borderline in size (left to right ventricle length ratio was 0.75) with aortic valve annulus 5.5 mm (−1.89 Z-score), mitral valve annulus 11.0 mm (−0.71 Z-score), fibroelastosis of the papillary muscles, and mild systolic dysfunction. The arterial duct was kept open with prostaglandin E1 infusion. Balloon valvuloplasty performed on the third day of life resulted in aortic stenosis gradient reduction from 84 to 15 mm Hg and trivial aortic regurgitation. Although systolic LV function normalized, increased left atrial pressure and supra-systemic pulmonary hypertension persisted during the first month of life. The LV was eventually considered hypoplastic, and Damus–Kaye–Stansel procedure with a modified Blalock–Taussig shunt and septectomy was performed at the age of 5 weeks. The patient was discharged with good right ventricular (RV) function and arterial oxygen saturation of 80%.

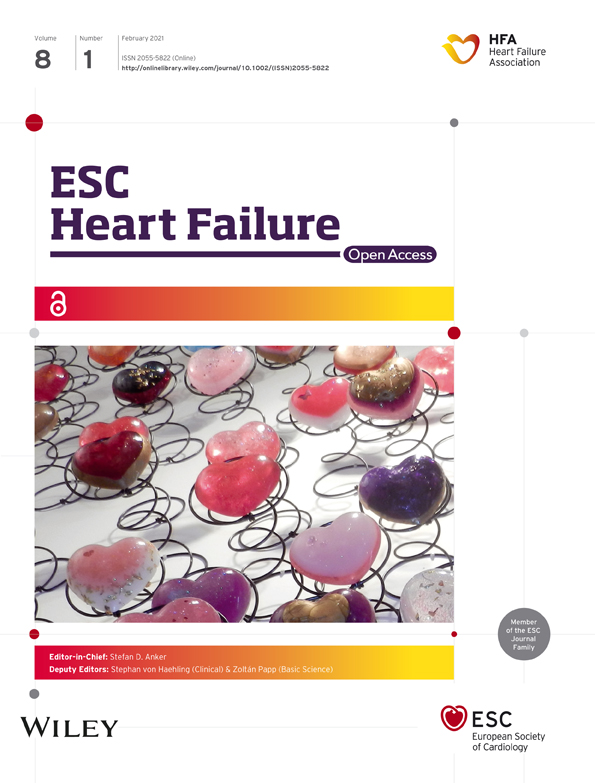

The boy underwent an uneventful bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis (BCPA) at the age of 8 months and total cavopulmonary connection (TCPC) at the age of 2.5 years. Catheterization before TCPC revealed favourable haemodynamic data (long-term development of haemodynamic parameters is shown in Figure 1).

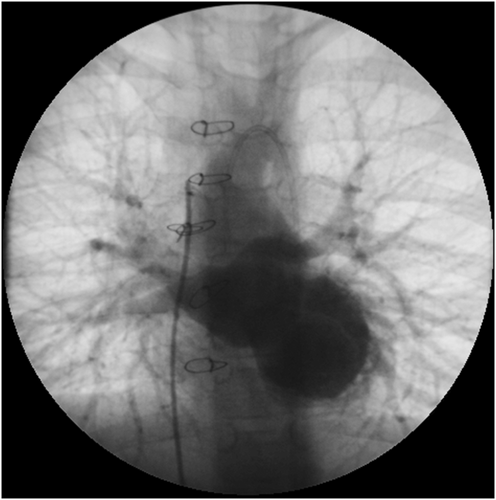

At the age of 5 years, severe protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) developed. Echocardiography showed compression of the right atrium by the extracardiac conduit with almost complete obstruction of the inter-atrial communication. The systemic circulation was completely supported by the borderline LV (LV end-diastolic volume = 81% of normal value) with good systolic function, adequate cardiac index, and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) of 14 mm Hg (Figure 2). It was decided to convert to biventricular circulation. The aorta and pulmonary artery were reconstructed and inferior vena cava re-anastomosed to the right atrium without any difficulties. No inter-atrial communication was found or newly created. Finally, 10 months later, BCPA was taken down and superior vena cava was re-anastomosed to the right atrium. The aortic valve did not require an intervention and there was no aortic stenosis after the biventricular conversion (gradient < 20 mm Hg). Three months after conversion to biventricular circulation, severe diastolic dysfunction of the LV and severe pulmonary hypertension became obvious. At repeated catheterization, LVEDP was 33 mm Hg, transpulmonary gradient was 40 mm Hg, and right atrial pressure was 12 mm Hg. Acute vasoreactivity test using oxygen was negative. Grade III of pulmonary arteriopathy using Heath–Edwards classification was confirmed by lung biopsy, and the patient was considered contraindicated for heart transplantation.

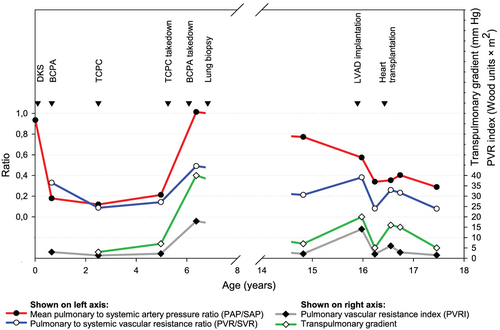

During the subsequent 8 years, the patient's clinical condition deteriorated progressively (New York Heart Association class III–IV). At the age of 16 years, the boy continued to suffer from severe cardiac cachexia and PLE, which was attributed to elevated central venous pressure as there was no anatomic stenosis of the inferior caval vein. He was treated with diuretics, angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitors, acetylsalicylic acid, prednisone, and subcutaneous immunoglubulins. At catheterization, LVEDP was 33 mm Hg, mean pulmonary to systemic arterial pressure ratio remained high at 0.77, but pulmonary to systemic vascular resistance ratio decreased to 0.21 and transpulmonary gradient to 7 mm Hg. Acute vasoreactivity testing using oxygen was positive at this moment. The measurements were, however, affected by general anaesthesia and low systemic blood pressure (61/35 mm Hg). Measurements may thus not have been reliable, and definitive conclusions about the degree of precapillary pulmonary hypertension and vasoreactivity were not possible at this point. The data also did not correlate with high systolic pulmonary artery pressure close to systemic as estimated from the tricuspid regurgitation jet using echocardiography (90–100 mm Hg). As a consequence, the patient was not considered to be candidate for heart transplantation at this point. Sildenafil treatment was started, and the patient was considered for left ventricular assist device (LVAD) as a bridge to candidacy for heart transplantation with a concept that pulmonary vascular disease may still be reversible. HeartWare HVAD® (HeartWare, Framingham, MA, USA) was implanted at the age of 16 years. On the first post-operative day, repeated suction of mitral valve leaflets into the LVAD inflow cannula occurred. The borderline LV did not allow enough space for mobilizing the LVAD, so it was decided to perform excision of the mitral valve, making the patient completely dependent on the LVAD (Figure 3). Repeated catheterization performed after 4 months on mechanical support showed a decline of pulmonary hypertension (Figure 1).

Heart transplantation was performed 6 months after LVAD implantation. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation had to be used for 4 days after the surgery because of initial graft RV failure caused by pulmonary hypertension. Additionally, the patient was treated by nitric oxide, epoprostenol, and levosimendan. The post-operative course was complicated by bleeding, arterial hypertension with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, renal failure, and superior caval vein thrombosis requiring catheter intervention. Autopsy of the explanted heart confirmed severe fibroelastosis of the LV.

Six years after heart transplantation, at the age of 22 years, the patient is in NYHA I–II functional class, has no mental deficit, and is attending a university (Figure 4). He has had no signs of rejection and his PLE resolved completely. Sildenafil treatment was discontinued 4 months after transplantation. Cardiac catheterization performed at the occasion of endomyocardial biopsy 1 year after transplantation showed normal mean pulmonary to systemic arterial pressure and pulmonary to systemic vascular resistance ratios.

Discussion

In a patient with a borderline LV, both univentricular and biventricular pathways have their specific risks. While univentricular (Fontan) circulation is a more conservative option, it brings a multitude of possible long-term complications due to venous congestion.6 In biventricular repair with a borderline LV, pulmonary hypertension is a major concern. Elevated pulmonary vascular resistance can develop and make conversion back to univentricular impossible. The decision is usually made during newborn age, but conversion to biventricular is possible later if the LV grows enough.7

In our patient, after an initial aortic valvuloplasty, univentricular circulation was chosen. Various LV scores calculated retrospectively would favour the same decision.3 The fact that there were persisting signs of pulmonary hypertension and Damus–Kaye–Stansel procedure was performed later than usual, at the age of 5 weeks, presented an undisputable risk. Despite this, Fontan circulation was completed uneventfully.

The next critical point was the conversion to biventricular circulation. Atrial septal defect restriction is one of LV recruitment strategies aimed at LV growth.8 In our patient, this was indeed the spontaneous development—inter-atrial communication obstructed gradually and the LV grew in size and supported cardiac output completely. We decided to proceed with conversion to biventricular circulation despite an elevated LVEDP of 14 mm Hg. Patients with LVEDP ≥ 13 mm Hg have been shown to carry a high risk of unfavourable outcome after biventricular conversion.7 Looking at the data retrospectively, staying with univentricular circulation and replacing the TCPC conduit to remove inter-atrial obstruction would seem as a more secure choice.

The indication of LVAD as bridge to candidacy for heart transplantation was made after 8 years of systemic-degree pulmonary hypertension. Assessing the degree and reversibility of pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension was difficult, despite favourable catheterization data at the time. Subsequent catheterization data revealed that the actual pulmonary vascular resistance was indeed high but also that pulmonary hypertension was still partially reversible. Nevertheless, complicated course after heart transplantation confirmed that the patient was probably right on the edge of transplantability despite being on LVAD for several months. The procedure itself and the post-operative course include all the complexity of heart transplantation in patients with univentricular physiology after multiple surgical interventions. The long-term outcome, however, may be comparable with published mortality data of heart transplantation for other forms of congenital heart disease.6

Conclusions

The presented case reflects well the changes in treatment options for severely ill patients with congenital heart disease and a previously lethal condition including the use of long-term mechanical circulatory support. An excellent functional result with a dramatically improved quality of life was achieved thanks to dedicated multidisciplinary care and the use of novel technology.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This study was supported by Ministry of Health, Czech Republic—conceptual development of research organization, Motol University Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic 00064203.